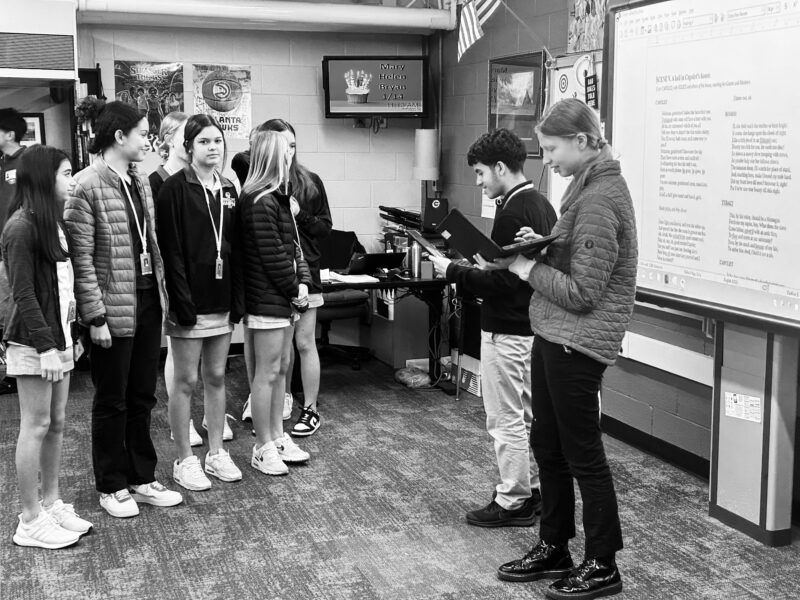

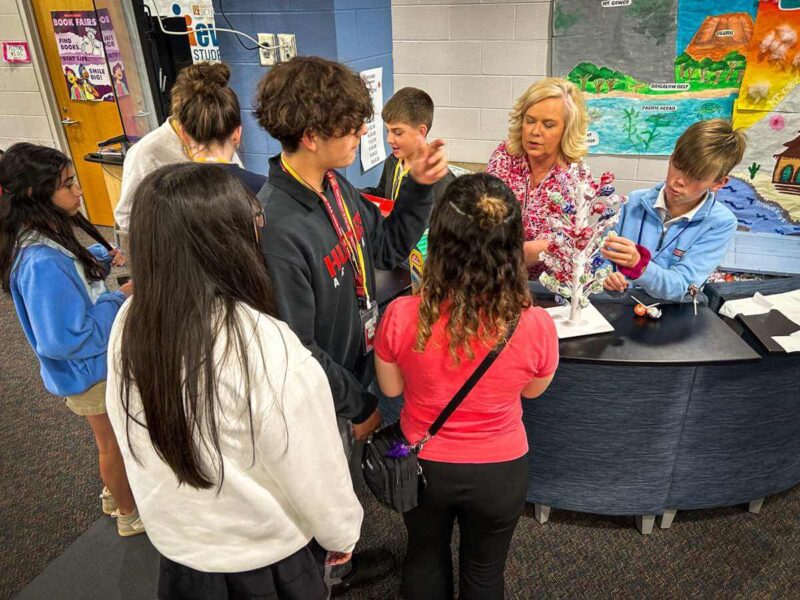

For about four years now, each of my classes during the book fair has picked out a poster that seems uniquely out of character for me, which they then all sign, and I hang it on the wall.

Previous years’ posters include two BTS posters, a Riverdale poster, and several kitty posters.

Today was our day in the book fair, so all classes picked a poster. They’ll be signing it tomorrow, and they should be on the wall by the end of the week.

This year, more kids seemed more interested in picking the poster. Usually, it’s just a handful of students in each class; this year, the whole class at times was inspecting the poster and making suggestions about which one to buy.

It made me feel exceptionally good.