Everyone has returned home; K returns to work tomorrow — the 2024 holiday season is over. The timeless magical period of Wigilia and Christmas and all the time preparing for it disappears, and the worries that for a few days we put out of our minds come crowding back in.

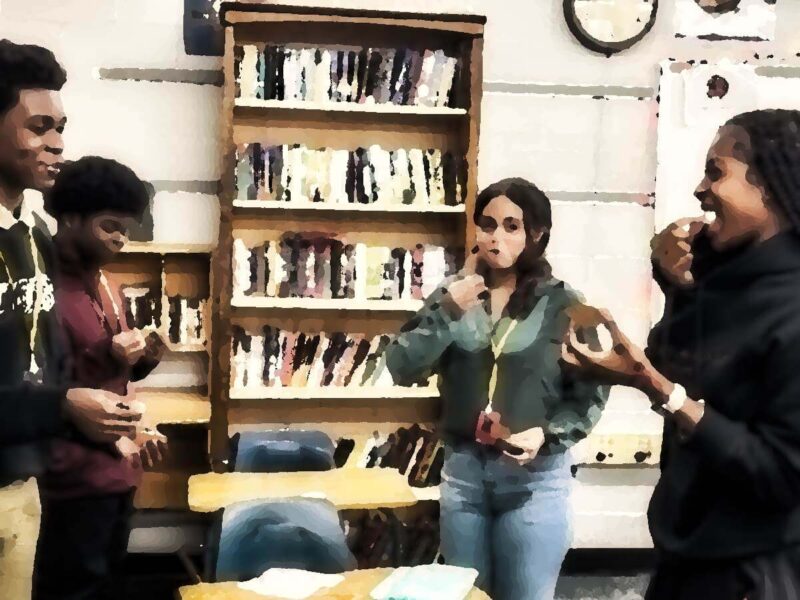

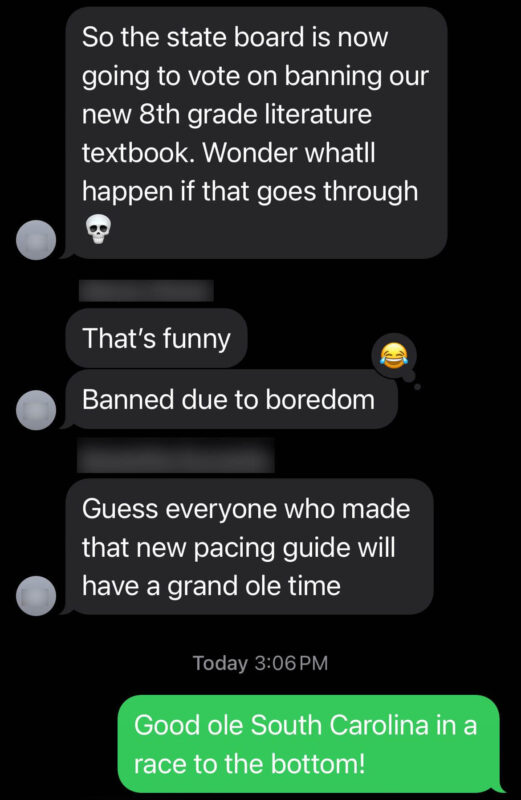

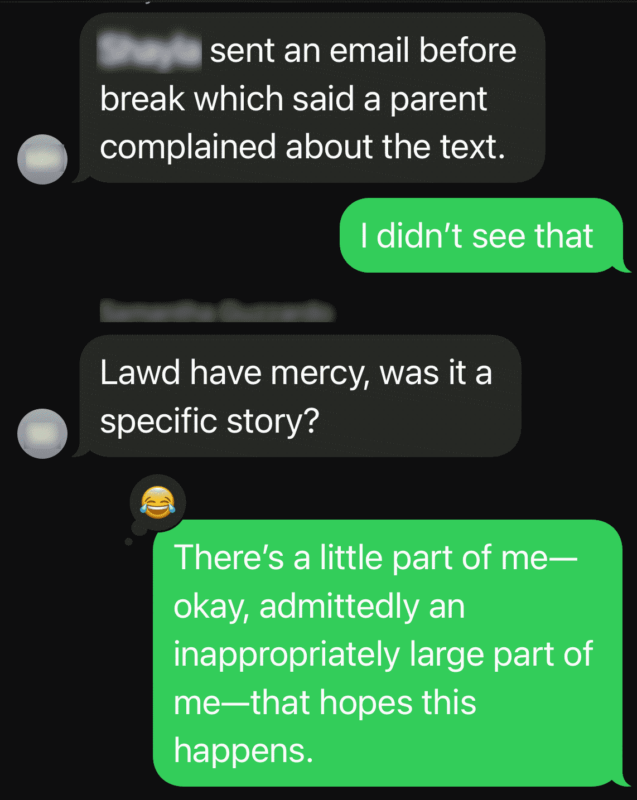

Worry 1

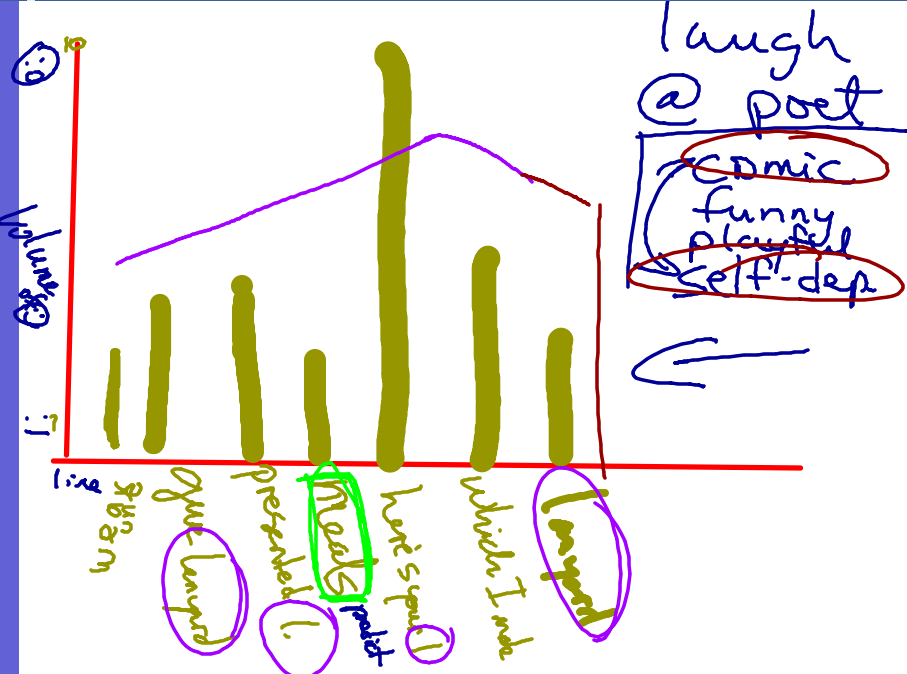

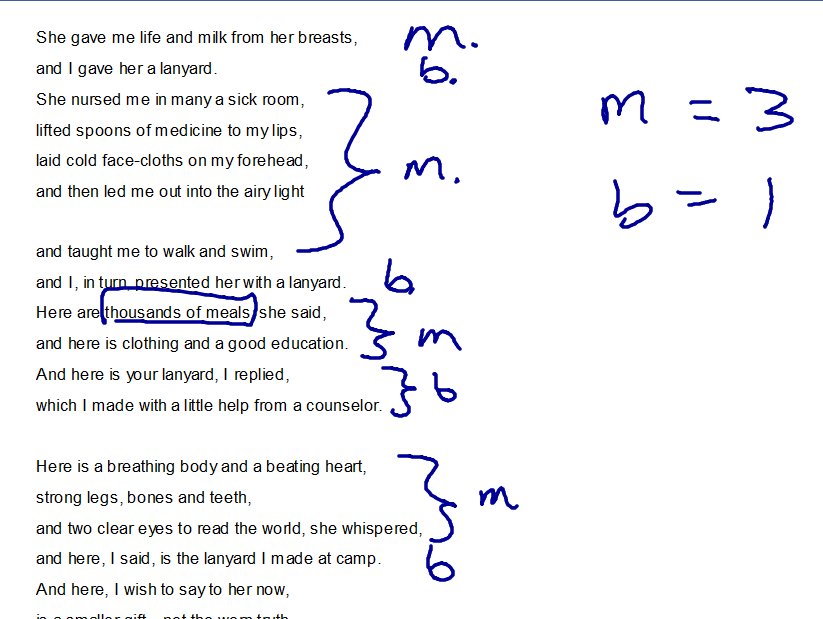

I woke up this morning thinking of school. The students are great — the best group I’ve had in years. The amount of micro-managing and mindless paperwork has increase so much over the last two years that it has me dreading a return. I’m left in a stressful quandary:

- stay at the school where I have a reputation, where I am (by administration’s own admission) the most frequently-requested teacher and put up with the increasing fiddling in every single decision I make while taking a little bit of comfort in the fact that that reputation serves as a bit of a buffer as I push back, or

- move to a new school (preferably a high school — I think all middle schools in the county are under the same micro-management stress: it comes from the district) where I am an unknown with no capital and no reputation, where it might in fact be even worse.

It’s a difficult decision that I’ll have to make very soon, and it entails a conversation with my school’s administration that I don’t really anticipate gleefully.

Worry 2

L is still recovering from surgery. It will take a couple of weeks. It’s still stressful to us all, though. It’s “Worry 2” instead of “Worry 1” because we know it’s temporary. She’ll recover; she’ll be able to breath better; her sinuses won’t be giving her constant headaches. So it’s a short-term worry — hence, “Worry 2.” But it’s our daughter we’re worried about: even when it’s a seemingly unfounded worry, we can’t just shake it off.

Worry 3

We have a leak in our roof. It might be under warranty from the company that replaced our roof a few years ago; it might not be. We won’t know until the company comes out and looks at it. But we’ve been on the list for over a week now. It took them forever to start the work in the first place. I’m not confident we’ll see anyone here for a long time.

And it’s supposed to start raining tomorrow afternoon and rain through the weekend.

I’ve got it tarped, but not sufficiently for a heavy rain. The location of the leak and the shape of our roof make it difficult to tarp. And we have no idea how long this will last.

Do we just call another company and take the hit?

Do we call insurance (they suggested calling the company that replaced it in the first place — a company the insurance adjuster had recommended, for the wrote our current roof)?

Worry 4

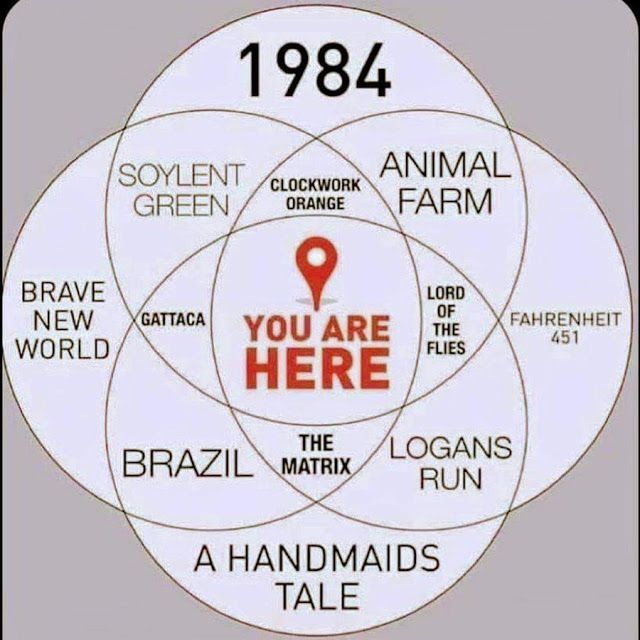

We have elected as president a narcissist who’s a convicted felon who tried to retain power by overthrowing the democratic process, a man who is, in every possible sense of the idea, completely unfit for the office. And some very worrying people will likely have an influence on him. People like Curtis Yarvin:

Yarvin, who considers liberal democracy as a decadent enemy to be dismantled, is intellectually influential on vice president-elect JD Vance and close to several proposed Trump appointees. The aftermath of Trump’s election victory has seen actions and rhetoric from Trump and his lieutenants that closely resemble Yarvin’s public proposals for taking autocratic power in America. (The Guardian)

When Trump takes office in a few weeks, it could conceivably lead to the end of America as we know it. Sure, the Republicans said the same things about Biden, but those fears were based on baseless conspiracy theories and good-old-fashioned hate-mongering. The people surrounding Trump aren’t being conspiratorial about anything: they’re saying it all aloud. They’re not holding their cards close: they’ve laid them all out with the Project 2025 manifesto and rhetoric people like Yarvin are saying.

Given the post-election period and Trump’s preparation for a return to the White House, Yarvin’s program seems less fanciful then it did in 2021, when he laid it out for Anton.

In the recording of that podcast, Yarvin offers a condensed presentation of his program which he has laid out on Substack and in other venues.

Midway through their conversation, Anton says to Yarvin, “You’re essentially advocating for someone to – age-old move – gain power lawfully through an election, and then exercise it unlawfully”, adding: “What do you think the actual chances of that happening are?”

Yarvin responded: “It wouldn’t be unlawful,” adding: “You’d simply declare a state of emergency in your inaugural address.”

Yarvin continued: “You’d actually have a mandate to do this. Where would that mandate come from? It would come from basically running on it, saying, ‘Hey, this is what we’re going to do.’”

Throughout the 2024 campaign, Trump promised to carry out a wide array of anti-democratic or authoritarian moves, and effectively ran on these promises. Trump has suggested he might declare a state of emergency in response to America’s immigration crisis.

Trump also promised to pursue retribution on individually named antagonists like representative Nancy Pelosi and senator-elect Adam Schiff, and spoke more broadly about dispatching the US military to deal with “the enemy within”.

Later in the recording, Yarvin said that after a hypothetical authoritarian president was inaugurated in January, “you can’t continue to have a Harvard or a New York Times past since perhaps the start of April”. Later expanding on the idea with “the idea that you’re going to be a Caesar and take power and operate with someone else’s Department of Reality in operation is just manifestly absurd.”

“Machiavelli could tell you right away that that’s a stupid idea,” Yarvin added. (The Guardian)

This is, of course, a worry that leaves me thinking, “This is all out of my hands — I can do nothing about it,” and yet. And yet…

So when the holidays are over, it’s not just a return to “normal” life. It’s that with a few additional stressors (not even all mentioned here) thrown in. We’ll get through it all, but it doesn’t diminish the stress levels.