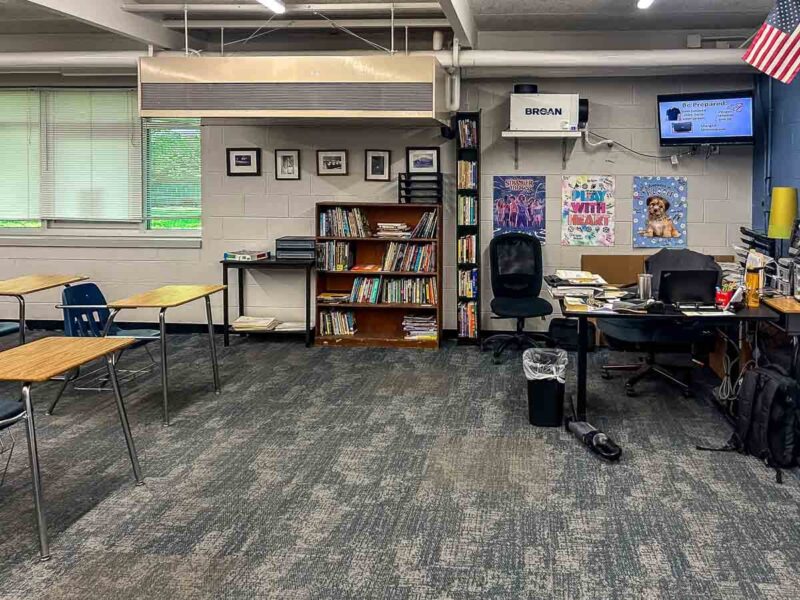

A few last pictures before I take everything down.

Our lives are filled with unconscious lasts — the last time we do this, the last time we do that. It’s rare that we encounter a last knowingly, consciously, purposefully. Retirement, weddings, births: these might count

Today, I pull into the parking spot I have used for years, shut off my engine, and sigh with the contentment of knowing it’s Friday. We’ll have a respite — some room to breathe. “Only a couple of more weeks of this,” I think, and running the news two weeks’ schedule through my mind, I realize that this is in fact the last regular Friday I will be teaching at this school. Next Friday is the eighth-grade field trip to Carowinds; the following Friday is the last day of school, hardly a normal school day.

Yet, truthfully, even today is not a typical Friday. A large portion of the students are on a band field trip to Carowinds, a theme park in nearby Charlotte, for a competition, and today our PTA is hosting the cooking for students who achieved all As throughout the year, which means several students will be out for a couple of periods. Given that we’re done with testing, none of us are engaged in any rigorous teaching with any of our classes at this point. So the last typical Friday passed some time ago, unnoticed and unacknowledged as so many other lasts.

For someone who likes to wallow in nostalgia as I do, such an epiphany brings everything into sharp focus. I step out of the car determined to notice and to appreciate every little feature of the day.

I cross the parking lot and begin up the sidewalk to the school, stopping at the dip in the sidewalk through which the roadway from the car drop-off line passes. A small grey car passes, but the large white SUV behind it stopped, the driver waving me across. I raise my hand in acknowledgement and smiling in polite gratitude, hurried my step. NEW ADD DETAILS

Up the sidewalk and to the right I turn, stepping through the puddle of dark water that sits continually at the end of the carline colonnade. Like the relatively-newly-redirected carline, this puddle is a new development. It forms from the drops of water falling from the stub of PVC pipe that breaks through the wall, slowly discharging the water drawn from the moist air of the classroom. Most classrooms received a dehumidifier earlier this year to deal with the high levels of humidity that often leave their marks in mold over the long summer. In the few short months the dehumidifier’s discharge has been dripping in that spot, a stain has formed and a small rise of sediment has formed, the beginnings of some kind of modern stalagmite. It’s only taken a few short months: who knows what it will look like after a few more years? In the past, I might have thought, “We’ll see over the next few years,” but I won’t see.

As I continue up the sidewalk, I greet a couple of students as they get out of their cars. There has always been such diversity in our population, and that’s clear from the cars in the line. One student gets out of a beat-up clunker; the next gets out of an expensive Mercedes. This diversity has always been a charm and a challenge at this school. I’m likely to have less diversity at my new school, and since it’s a charter school that one must apply to attend, I’ll likely have few if any at-risk students. I’ll miss that, to be sure, but I won’t at the same time. Working with kids saddled with trauma is exhausting, almost to the point of trauma itself.

After I check my small cubby of a mailbox, I head down the hallway to my classroom and pass two of our Spanish teachers, a gentleman from Columbia and a young lady from Peru. They stand in the corridor chatting in Spanish. As I pass, I understand a word or two but nothing more. Suddenly I remember doing the same in the small high school in Poland where I taught for seven years. “That’s what we must have looked like standing in the hall chatting in English,” I thought.

Leaving that school for the first time in 1999 was so wrenchingly difficult. Not knowing when I’d be teaching again and already missing the adventure of living abroad, I sat numbly in a small bus with the village drifting by one last time as I headed to Krakow to leave for the States. I knew that ending was coming, too, but the uncertainty that followed was awful. Now, I know exactly what I’ll be doing next year, and knowing I’ll still be in a classroom transforms my departure into a transition.

Shortly after I enter my room, my first student arrives. A young lady in my homeroom and honors class, EC is a conscientious student who stresses entirely too much about getting everything right. She puts her materials down and begins typing something on her computer.

“EC, did you realize that this is your last regular Friday in middle school?”

She smiles. “Yes, sir,” she began, always such a polite Southern girl. “Julie, Alison, and I were just talking about that last night.” Girls after my own sentimental heart.

“We so often move through lasts in life,” I continue, “and we don’t even realize it’s the last.”

“Yes, sir,” she replies, still smiling.

“It’s good to be conscious of and acknowledge those lasts,” I say. “To enjoy them. To cherish them. To savor them.”

“Yes, sir,” comes the response. EC’s smile suggests that she is just being polite, and since no one wants a lecture at eight in the morning, I let it go. Still, it’s heartening to see someone so young being introspective about life instead of just gliding through it without thought. Of all my students, I would have put EC high on a list of potentially self-reflective students.

A few moments later, Tonia, another student in EC’s honors class, bounces in. Tonia has always been all smiles. She, too, is somewhat introspective: she has a charming nickname for herself whenever she does something she regards as, in her words, stupid — Ton-key Donkey. It’s rare that a middle school student can be so freely and jocularly self-derogatory. It suggests a maturity that is rare in middle schoolers, a maturity that makes a student stand out, makes a student shine.

“Did you see my email, Mr. Scott?” she asks with her usual lilt.

Loading my email, I explain that I haven’t had a chance yet. She starts waving her hands to warn me off.

Tonkey-Donkey messed up!! I submitted the comprehension questions and got a 78% on them! I am confused about what I could have gotten wrong and I’m worried about how much it’s going to bring my grade down. Is there anything I can do to bring my grade up? Thank you!

As she begins explaining, I exclaim, “A 78!?!”

She buries her face in her hands in playful, mock (but not entirely so) shame. “I know! I can’t believe it. I don’t know what happened. I thought everything was fine and then I submitted and saw the grade. A C! A C! Mr. Scott, I never get Cs. Ever. One time, okay, one time, but the teacher gave me a chance to raise the grade. Some students might get a 78. I don’t get 78s! Ever! It’s going to bring down my grade so much! This is awful! I couldn’t sleep last night because I was worrying about my 78. Well, 77, but it’s 77.5, so you’ll round that up to 78.” All of this flows from her in what sounds like one breath as she hops from one foot to the other and gestures wildly with her hands as she explains the looming tragedy.

Together, we look at the questions she got wrong. They’re questions about the end of To Kill a Mockingbird, specifically about how the sheriff, Heck Tate, tampered with evidence to make it look like Bob Ewell fell on his knife. Students never get the intricacies of that passage, and we’ll go over it once everyone is done with the book.

“I thought I’d set the value of those questions to 0 so they don’t affect the kids’ grades,” I think, almost muttering out loud to myself and making a note to go back and change that value.

“Is there anything I can do to raise my grade?!” Tonia begs.

Such a sweet child, and such a wonderful student. She’s in my class because her mother requested it. In truth, it’s because I requested it. Tonia’s little brother played on E’s soccer team a couple of seasons ago, and Tonia’s mother asked if it would be possible to request she be in my class and how she might go about doing that. “I’ll just put in a request for her with the counselor,” I said that spring afternoon. Had I known Tonia, I would have made the request without any request from her mother, so charming is Tonia.

As we’re talking, another girl from a different honors class comes in to tell me that she’s completed an assignment that is marked as “Not handed in” (NHI in our district parlance). She’s not worried about the grade as much as the fact that she never — never — gets NHIs. She’s okay with me changing it to GFA (Grade Floor Applied), which will have the same effect on her grade as “NHI” but without as much of the stigma she’s attached to it.

Most of my students next year will be like this. There will be few (if any) students who have a majority of NHIs in the gradebook. District policy mandates that NHIs count as 50s rather than 0s. In other words, ten points from a passing grade. The thinking is reasonable: if you have an extremely low grade from zeros, it’s likely to discourage you from doing anything about them. There’s no way to come back from that. With 50 as the grade floor, students can recover. The problem is, at the high schools, there is no grade floor. These 50s will suddenly be 0s, and kids who skirt by with 60s as a result of the middle school grade floor will find themselves with grades in the thirties or forties in high school. The common sentiment is that the district is setting them up for ultimate failure with this grade floor, but there’s nothing we can do but comply.

“There will be no 50 floor at this school,” the principal at my new school announced at the in-take meeting last Saturday, and this announcement received rather vigorous applause from the parents.

As these virtually-simultaneous conversations bounce along, I notice two of the four Muslim students on our team have come in to join the two in my homeroom. Three of the girls are from Afghanistan; one is from _______. They chatter away in a mix of languages. The ______ student explains that she can understand a bit of the Dari the other girls speak, and since Arabic and Dari use the same script, she can sound out the written language, “but I can’t say anything,” she laughs.

One of the girls, Asmaan, comes up to discuss a small assignment she has. New to America, Asmaan speaks very little English. This is, in part, because of her lack of experience with the language, in part, because of her reticence to speak. She’s a quiet girl no matter the language, and that is obvious when she begins discussing her assignment. Her class is reading The Diary of Anne Frank, and I procured for her a Dari version of the original diary, which she is reading on her own. My assignment to her was to find three ways that she and Anne are similar and two differences. Asmaan shows me her Chromebook, which is open to Google Translate, where she has written in Dari to translate to English: “Anne is very talkative, and I am not.”

“Yes,” I begin slowly, “but I want you to say these differences. To speak.”

At first she misunderstands, feeling confused about the parameters of the assignment. Once we clear that up, she heads back to her desk to practice saying her handful of sentences.

I wonder at the similarities and differences she will find beyond the obvious. As a young Muslim girl who wears the hijab, she stands out and in some opposition to the society around her, much like Anne. Does she see that similarity? Even if she does, will she willingly admit it?

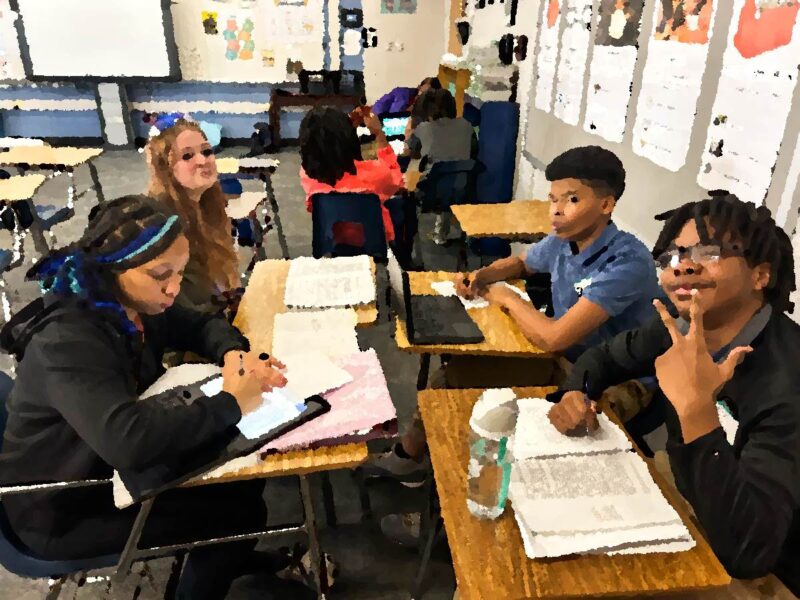

The first of two honors classes begins and students form their literature groups. All of my classes are working in independent literature groups, but most of the

During class, Jessica, confused about one of the questions, comes to discuss it with me. The question is about one of the passages in Mockingbird that most students miss:

Mr. Tate reached in his side pocket and withdrew a long switchblade knife. As he did so, Dr. Reynolds came to the door. “The son—deceased’s under that tree, doctor, just inside the schoolyard. Got a flashlight? Better have this one.”

The question is meant to see if students made the correct inference about what Heck Tate was about to say to Dr. Reynolds: “How does the conversation about the attack change the reader’s opinion of Heck Tate?” The correct answer is “We realize he hated Ewell just as much as everyone else did,” but most students struggle with that passage.

It’s not the only scene from the novel that students struggle with. Students in the next period are trying to figure out what the three versions of Bob Ewell’s attack on the children could be. “There’s what Atticus thinks happened,” I explain every year, “then there’s what Heck Tate is going to say happened, and finally, there’s what really happened.” The first two are fairly straightforward; the third, the truth behind Tate’s lie, eludes students and always has. The key to the mystery is actually in the passage above, which is the real reason I ask students to re-examine it.

Mr. Tate reached in his side pocket and withdrew a long switchblade knife. As he did so, Dr. Reynolds came to the door. “The son—deceased’s under that tree, doctor, just inside the schoolyard. Got a flashlight? Better have this one.”

“I can ease around and turn my car lights on,” said Dr. Reynolds, but he took Mr. Tate’s flashlight. “Jem’s all right. He won’t wake up tonight, I hope, so don’t worry. That the knife that killed him, Heck?”

“No sir, still in him. Looked like a kitchen knife from the handle. Ken oughta be there with the hearse by now, doctor, ‘night.”

Mr. Tate flicked open the knife. “It was like this,” he said. He held the knife and pretended to stumble; as he leaned forward his left arm went down in front of him. “See there? Stabbed himself through that soft stuff between his ribs. His whole weight drove it in.”

Mr. Tate closed the knife and jammed it back in his pocket. “Scout is eight years old,” he said. “She was too scared to know exactly what went on.”

I want students to notice that little detail, the switchblade. Good writers do not just drop details in a scene for no reason. The switchblade must be somehow significant. To make sure readers see that, Lee refers back to the switchblade a few pages later:

“Heck,” said Atticus abruptly, “that was a switchblade you were waving. Where’d you get it?”

“Took it off a drunk man,” Mr. Tate answered coolly.

Sharp readers realize that it is in fact with that switchblade that Ewell attacked the children, that Tate found Ewell with a kitchen knife in his gut and a switchblade in his hand making it impossible to suggest that he fell on his own knife, thus shielding Boo Radley from the town’s attention.

Next week, we will go over these passages as a class, and with a gallery walk I hope to nudge the students to these realizations. These are honor students: they will continue putting forth their best effort even knowing that grades and testing are all behind them. Indeed, that is, in large measure, why they are honor students: they’re really no smarter than most; they’re just harder working.

Sixth period students are finishing up the play version of The Diary of Anne Frank in literature circles, and since some students are further ahead than others, some students only have a few minutes of work on this Friday afternoon. A couple of Latina students, Valentina and Gabriela, come up to talk to me about a problem one of the girls is having with one of the Latino boys in class. Valentina has her Chromebook open with a translation of what she wants to say.

“No, no!” I scold her playfully. “Take that back to your seat and learn to say it.”

Valentina heads back to her seat, but Gabriela stays at my desk.

“What’s this about?” I ask Gabriela. Of the four Latina girls in his class, Gabriela speaks English the best and often translates for the other girls when sticky language issues arise.

“Luis keeps saying stuff to her, calling her names,” Gabriela explains.

Finally, Valentina, who’s been practicing in the back corner, comes back and explains what’s going on.

“In English or Spanish?” I ask her.

“In English and Spanish,” she explains.

Though I rarely do so, I ask Gabriela to translate for me: “Unfortunately, at your age, a lot of kids just act childishly. It’s best just to avoid such students.” I know it’s not the best solution, but how else can I deal with one student simply being childish to another? “Someone has to be the adult,” I conclude, and Valentina nods.

I feel a little guilty about my non-native English speakers, or as the common jargon labels them, MLs, mult-linguals. I never feel I’ve done all for them I could have. Asmaan is also in this class, and I feel I could have done so much more for her. I blame the district in part: dumping these kids into regular classrooms with very little direct English language instruction seems terribly unfair and awfully ineffective, but I have no say over district policies developed in turn from state department of education policies that seem at best discriminatory. But that’s just an excuse: I could have done more, and I, often tired and frayed, simply didn’t put in the extra planning and preparatory time necessary for such students. I could, in turn, also push this onto the district: we have so many required meetings and so many administrative responsibilities (many of which feel completely arbitrary and useless) that our planning time during the day disappears into a seemingly-endless stream of meetings and surveys. In the end, I must face it: I could have done more.

Seventh period files in, and noticing the sound meter still projected on the Promethean Board from the last period, several of them begin screeching and whooping to see just how high they can make the meter go. This maturity disparity often differentiates the honors classes from the on-level classes, and this difference continues into the class itself. Students are to work in self-directed reading groups to complete The Diary of Anne Frank, and the more mature students do just that while the less mature students, the ones often with behavior issues, mountains of NHIs in the grade book, and a long string of disciplinary referrals, use the time to entertain themselves with conversations and silliness. It’s the end of the year, though: testing is over, and I have already drained myself with this class. I make the decision to let them be.

Karma will catch them, I assure myself. In time, they will have to find a job and support themselves, and they will find it difficult to keep a job with their inability to stay focused and on task for more than (with some students, literally) ten to fifteen seconds. I don’t want their lives to end up like this, and I’ve repeatedly sketched out the contours of their futures if they don’t develop better habits, but I’m tired: even Sisyphus could push only so hard.

Aside: it was eighteen years ago today that I accept my current job.

Cherry trees are blooming in the courtyard between the seventh- and eighth-grade halls. The other day, I walked the kids that way to lunch: it’s out of our way, but I thought I might enjoy some fresh air. Perhaps they would, too.

“Mr. Scott, can we walk through the blossoms to lunch again?”

Now, we do it every day. At their request.

Monday after break is always a bit of a mystery. No one really knows how the kids react; for that matter, nobody really knows all the adults are going to act. Some of the kids are reluctant to go back to school. and it shows in the apathy some of the adults are more reluctant to go back and it shows in their snarkiness having spring break. This relatively late in the year is also tricky. We’re into our final quarter, but with benchmark testing, in the beer, testing, access testing, probably some math testing for some students field trips, field days, half days, and like we really only have about seven weeks or so of school after having a week off it’s difficult to get motivated for seven more weeks. It feels like an afterthought

For me, with this being my last year at Hughes, it hits a little differently. Some of the kids were routing; some of the kids were focused; most of the kids were somewhere in between. The day slipped by relatively uneventfully and I returned home a quarter as of course 45 days long. I closed my car door and said aloud, “44.” 44 more days in Greenville County schools 44 more days these kids. 44 more days to wrap up 17 years. So both a little sad about it and quite excited at the same time.

It was, of course, the first of many last, and I’m glad that I am aware at this point that this is the last time I’ll be doing some of these things. The honors kids are finishing up little roaming and Juliet papers for all. I know that may be the last time that I run through the particular assignment with a group of students. After next year, I will have the option of going back to English, but if things go as well as I’m hoping, I don’t know that I’ll want to. In English 8, we will soon be starting The Diary of Anne Frank, and that would be the last time we run that unit. We read the play, and we act out most of the first act in class. While I’m not sure how much they learned about English and how they learned a lot about the holocaust a lot about the horrors of living under Nazi occupation, and since they are the same age, they learn a bit about themselves as well. It’s always been one of my favorite units to teach.

So today was a bit of a mixed bag. It was fun and exciting: it was so exhausting.

This final quarter is also another last for our family, and this is much more significant: this is the last quarter Lena will be living with us during the school year. That ending has come all too soon. It’s a parental cliche to wonder where the time went, but when you’re living at it it’s not a cliche anymore.

The new school I will be teaching at next year doesn’t even physically exist yet. For most of next year, we’ll be operating out of a high school. Today, though, was the groundbreaking for the new facility.

Four sweet, dark-haired, dark-eyed girls crowded around me and asked, almost in unison, “Can we go to the media center during lunch?” It’s Ramadan, and my four Muslim students (three are from Afghanistan and one is from Syria) are eager to avoid even the sight of food while they are fasting. They cluster together throughout the whole day: the guidance counselor purposely made their schedule so that they have almost every class together since they feel safest with each other.

Of course, I agreed for them to go to the media center: growing up in a strange Christian sect that borrowed all the Jewish festivals, I had to fast one day a year during Yom Kippur, though our sect preferred the translated name, the Day of Atonement. I have a slight sense, then, of the challenge my Muslim students face, though only a very slight sense: we didn’t go to school or work on the Day of Atonement, and it was only one day. I can’t imagine what it would be like to fast all day and to go about one’s regular schedule at the same time, so I’m certainly sympathetic to the difficulties they face this month.

When we got back from lunch, the girls were waiting at the classroom door. They came into the room and immediately asked if they could go pray. “If we don’t pray while we’re fasting,” one girl explained, “it doesn’t count.”

I looked at them quizzically: “Why didn’t you pray while you were in the media center during lunch?”

“It was too early,” another of the girls explained.

The skeptic in me wondered if they will start asking questions at some point. Would a truly good god be so upset that you prayed a few minutes early? Would a fair god be obsessed with females’ modesty in clothing while ignoring males’ modesty? Would a wise god really be all that worried about what animal you eat? These were the same kind of questions I asked myself years ago, and when I dallied in Catholicism a few years ago, I didn’t find resolution to these issues; I just temporarily stopped thinking about them. But once they’re there…

Since I made it official that this will be my last year at Hughes Academy, I have noticed a change in how I view things. “Don’t check out these last few weeks,” Kinga said to me. I replied that this was the last batch of students I’m sending to local high schools, and I want my reputation to remain intact. Several teachers have told me that they can tell who my students are after the first major writing assignment. I don’t want that to change this final year.

Still, my stress levels on some things have declined greatly. Today, for example I saw a kid with his hoodie still on, and I told him to take it off. He said he was going off to PE and would take it off afterward. I knew it he is not supposed to have it at PE, but in the end I just let him go. Karma will catch up to him, I thought sure enough, an hour later, I saw him standing in the hall, being dressed down by the principal for wearing his hoodie.

Another example occurred last week. One student was extremely disrespectful with me, and this disrespect came immediately upon being told that he needed to vacate the hallway and make it to class. I’ve had encounters with a student earlier in the year, and none of them have been pleasant. I can only imagine how much chaos he brings to the classrooms he attends. I thought that perhaps I should write him up. That would be a mild blessing for his teachers because a day without his problematic behavior is like a day of vacation. You can get things done that you couldn’t get done otherwise. Still, in the end, I decided it was just not worth my time. I’d have to call his mother, and I’d have to find that phone number by going to this teacher or that teacher and tracking it down. I wouldn’t have access to it myself. All that being said, I just decided it was not worth my time.

Tech-free day — which means students couldn’t use any technology. And they had to look up a couple of unknown words…

For many years, the end of the school year was something of a relief. I had completed another year of instruction; my students were moving on to bigger challenges; and I would be able to rest for a while. The school year was always a challenge, but it was never anything insurmountable.

Then a few years ago, every school year started to feel a little more like the myth of Sisyphus. I was rolling the boulder up the mountain year after year, but at least when I got to the top, even though I knew it would roll back down, I always had some satisfaction that I had indeed pushed it up the mountain to begin with. Over the last few years, however, when I reached the year’s pinnacle, when I have pushed that boulder up the mountain one more time, I stand there, waiting for it to roll back down. Instead of turning my attention to summer break, I just watch the boulder tumble back down the hill as I think, “Well, I’m just going to have to roll it back up again next year.”

Part of that was a function of exhaustion, I’m sure. Yet part of it arose from the nervousness I felt, and I believe all teachers feel, as one year ends, and the next one begins. It’s been the same worry every single year: What else are we going to have to do next year that just feels like jumping through a hoop?

In short, I’m tired of jumping through hoops to provide data for people at the district office who need to produce something that justifies their six figure jobs. Reports and charts require data; we teachers provide that data. Lately, it’s all I feel I do. I’m sure it’s somewhat debatable how accurate that description is, but it is how a lot of teachers feel today not this in our school, not just in our district, not just in our state, but all across the country. All teachers are tired of the increasing administrative requirements, the increasing data analysis requirements (often analyzing data of questionable value to begin with), and the increasing number of silver-bullet computer programs and websites, which don’t solve problems, but usually only create more work. Teachers are tired of those who hold the purse strings dictating how things are going be done when most of those making legislative decisions have never been in a classroom to begin with. Teachers are tired of “solutions” which are nothing of the sort, but rather simply legislation controlling the one thing that we as a society can legislate about: teachers.

Teacher are leaving public education in droves these days, for the aforementioned reasons and likely many other others. I am afraid that I have decided I must join those ranks.

Effective at the end of the 2024-2025 school year, I resign my position at [this school].

I leave [this school] with a certain degree of sadness, to be sure. I have taught here for so long and created such a reputation for myself that it is quite difficult to give all that up. Students coming to my classroom know what to expect. Students who have older siblings whom I taught arrive expectations based on stories their older brother or older sister told them. Parents who have talked to the parents of former students greet me with smiles on Meet the Teacher night and tell me they are eager for their son or daughter to receive the challenge, which, according to my reputation, I am able to provide. Former students come to see me regularly, and it’s always a delight to talk to them. In leaving [this school], I leave all that behind. It is a sacrifice I don’t make lightly.

However, I believe I have accomplished everything I could have accomplished at [this school], and it is time for me to move on. Other challenges await, and I am eager to take them on.

When you go for your first interview in years, it might be a semi-stressful event. After all, you’re out of practice.

You haven’t done this for so long you might not prepare properly. You might forget the name of the teaching model the school uses, and on the way to the school, you might have to refresh your memory at a traffic light.

You might have forgotten the stress of wondering if you’re going to be on time: you left with plenty of time, but who knows what delays await you, especially on Southern roads. It could be road work; it could be a traffic jam; it could be awful roads; it could be someone going ten miles under the speed limit.

You might have to schedule the interview just at the tail end of your day, and in an effort to be a little subtle about things, not come to school dressed for the interview but attempt to make the switch on the way. A service station bathroom? Too long. GPS says I only have eight minutes to spare. Traffic lights for the shirt and tie; remote corner of a grocery store parking lot near the school for the pants.

You might have to go to the restroom when you arrive but decide there’s just not the time (even after checking in with the receptionist), and besides, it’s not that urgent.

You might have forgotten that you’re not strictly (or even nearly) wearing dress shoes because you’ve gone all in for zero-drop shoes and don’t own a pair of formal zero-drop shoes, and you realize you probably should have bought some. In the meantime, you try desperately to remember not to cross your foot on your knee.

You might find yourself talking too much and have to tell yourself to shut up. “It shows your passion,” you might justify later. Perhaps your right.

First interview in seventeen years — went alright. We’ll see.

Today we covered 3.1 — Tybalt kills Mercutio, Romeo kills Tybalt, and the prince banishes Romeo.

“When you get to the third act of a Shakespeare play,” I’d explained to the kids yesterday, “everything changes.”

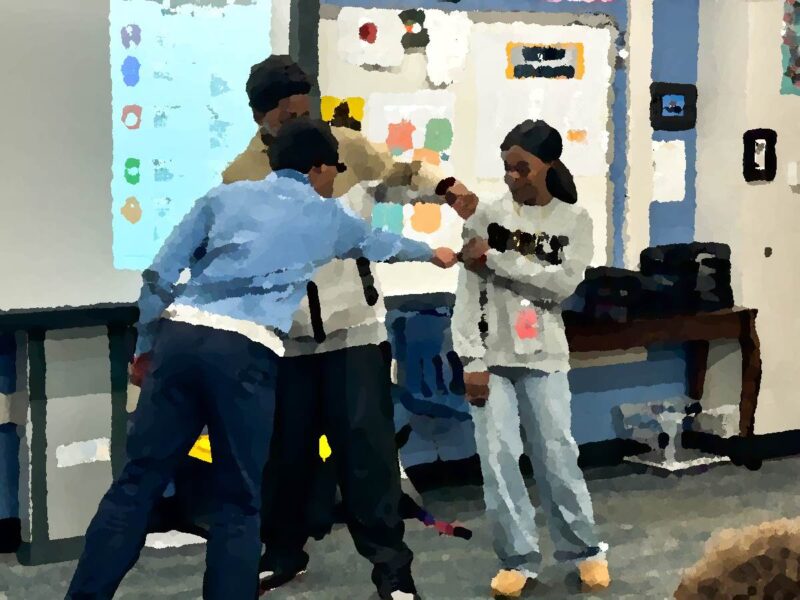

I’ve always especially enjoyed the lesson we do for 3.1. The kids select various divisions of the scene, read and discuss those divisions, and then prepare a tableaux vivant to summarize it. Kids who get the latter part of the scene quickly call me over to check their understanding.

“Wait, Tybalt is dead? How did that happen?”

“You mean Mercutio is gone? What?!”

My answer to all such inquiries is the same: “When you guys present your tableauxs, you’ll see.”

I’ve been working at the same school since 2007. The end of this year will mark the seventeenth full school year I’ve taught there. I began in a room at the end of the eighth-grade hall; at the end of my first year, I was moved to the top of the hall, put on another team, and given my first English I class to teach. I’ve been in that room ever since. Sixteen years in the same classroom.

At this point, by my count, there are only four teachers who have taught at that school longer than I. Two are retiring at the end of this year. I would be number three in seniority. I know one of those two teachers is planning on retiring after next year, and so I’d move up to number two.

In a lot of ways, that’s an admirable goal. It’s a rarity in today’s world, though. Changing jobs every few years seems to be the rule and not the exception. Still, I always thought that there was something rewarding about sticking around and mastering a position. And there’s something in me that thinks it might be a real kick to reach that point: no one has taught here longer than I.

But what happens when the requirements of supervisors (in this case, people at the district level) make it difficult to continue teaching in a middle school with a clear conscience? What happens when you start to feel complicit in the systematic over-testing of students? What happens when the amount of stress you feel from jumping through all the hoops the district puts in front of middle school teachers begins to overshadow the joy of the job itself? You pull out your resume, which you haven’t updated in well over a decade, polish it up, write a cover letter, and start applying for jobs at high schools.

The Boy and I headed out for a walk after dinner. We took the dog, we chatted about school, keyboards (as in computer keyboards — a recent interest of the Boy’s), district band tryouts (tomorrow evening), and random topics (as if that list weren’t random enough). It was another of those “how many more times do we do this?” moments. The Girl didn’t go with us because she had gone to her boyfriend’s house to watch a movie with him.

Everyone’s role slowly shifts.

In the South, we don’t know what to do with snow. When it falls, everything comes to a halt. There are long lists of closures and delays on every local website — first and foremost, schools. Our district posted this today ahead of snow that’s suppose to start around noon tomorrow:

Greenville County Schools will have an eLearning day Friday, January 10. Schools and office buildings will be closed. All activities, including athletic events and field trips, are canceled on Friday and Saturday. The District’s ICE (Inclement Conditions Evaluation) Team evaluated the forecasts, and the decision was made based on the predictions and timing for snow and/or ice accumulation, which may result in unsafe road conditions, downed power lines, and loss of electrical services.

Because we are an approved eLearning district, this day will not have to be made up and instruction will be provided through Google Classroom. Students will complete eLearning assignments later if they are unable to participate due to power outages, lack of internet service, or other barriers. Once operations resume, school personnel will begin rescheduling events as appropriate. Please check local media, the district website, and the district’s social media for the latest information on school closings or delays.

I have mixed feelings about this: elearning days are seldom very productive because so many students, for whatever reasons, fail to log in and do the work. Teachers almost always give light work during that period because they know so few people will show up. Knowing this, a few more students decide not to show up.

But at least we’ll be able to play in the snow. In theory.

First day back of the new semester. Being with the kids again reminds me of why I continue teaching: it’s an incredible feeling to realize my job is simply to help a bunch of really great kids. Did everything go perfectly? Of course not. Were there some magnificent moments? Of course there were.

Could I have used another few days of break? Of course I could — but not from the kids. Not from the kids. From the paperwork, meetings, and bureaucracy.

Today was our first day back in the building. It was, mercifully, a teacher workday. It’s a good way to begin the new semester: I had time to do some serious planning in the morning, and I worked with the Special Ed teacher who co-teaches one of my classes to figure out some effective ways of simplifying a terrorizing, difficult text that’s in our textbook. That’s how I spent my morning. I could have used the afternoon to prepare some of the materials we’d planned on using and to create some differentiated (i.e., simplified) versions for some of my students who are still learning English. (I’ve got seven students in one class alone who speak very limited English, including one who speaks almost no English. She needs a specialized English class for absolute beginners, not anything I can give her. But I’ll be damned if someone is going to be in my class and not learn something, so I make special mini-lessons for her that I squeeze in here and there. Otherwise, she works on Rosetta Stone.) Still, we didn’t have that time.

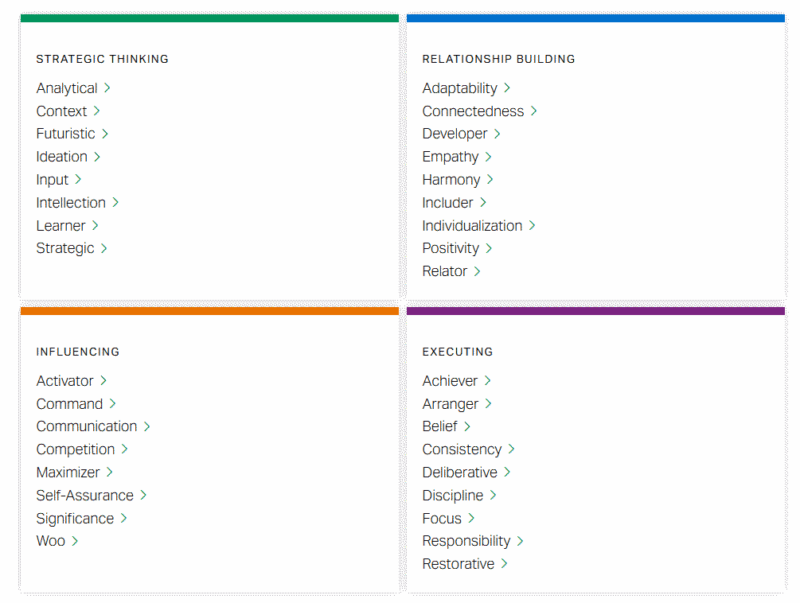

Instead, we had a Clifton Strengths Finder session. Earlier in the year, we were asked required to take a survey to help find our strengths. Each question had two activities and you were to pick which one you preferred and to which degree, and there was a neutral option in the middle. For example, it might be something like this:

Imagine it’s time for dinner. What are you more likely to do: pick the restaurant or decide to stay home? What an idiotic question! It depends. How tired is my wife? How tired am I? How much money do we have? What do we have in the refrigerator? What time is it? What plans do we have after dinner? I picked neutral.

Another one: Imagine you’re speaking to community leaders. Are you the “let’s get started now” type or the “No, I don’t eve want to do that” type? Again, that depends. What am I talking about? How long am I expected to speak? To what end am I giving this speech? Do I even support the cause? Is this something likely to affect change or am I just a figurehead speaker? I picked neutral.

A third example: Imagine your boss asks you to work on a big project. Are you a big picture person or do you need details? Once again, it depends. What is this project? Do I feel it’s in my scope of expertise? Will I be working on this alone or with a group? If it’s with a group, what role will I be playing? What is the timeframe for this project? What is the budget? I picked neutral.

A final example: Imagine you’re receiving an award. Would you want individual recognition or would you insist on recognition of the team effort. Bet you can guess where I’m going with this one: it depends, damnit.

Almost every one of the questions was like this. I picked “Neutral” over and over and over — for most of the 190 questions. (Yes, 190 questions. Are these people insane? Does district administration think I have nothing better to do with my time than read 190 poorly-conceptualized questions?)

Just before break, I got an email from the district office politely requesting me to take the survey. I did take the survey. We don’t have your data results. (New Year’s Resolution: I am so sick of hearing the word “data” that I have sworn I will not use it myself at all in 2025. I hate that word now, oh how I detest it.) Well, I know I took it. But we don’t have your results — the session won’t be as meaningful for you if you don’t take the survey.

When I logged back in, I saw a message: “We were unable to tabulate your survey because you selected ‘Neutral’ too frequently.” Well, that’s what I get for thinking. I explained this in yet another email. Can you please take the survey again? Fine, I’ll take the survey.

For probably 175 of the 190 questions, I randomly chose any of the options other than “Neutral.” In fact, if I’d thought about it, I would have had one of my students come in during planning and pick them randomly for me: it was such a hassle because the survey software was so poorly programmed. Sometimes the “Submit” button worked the first time, sometimes I had to click it twice. Still, for about 15 of the questions, something caught my eye in the wording or the responses, and I actually answered those questions truthfully.

Today, we got those results back. Strangely and somewhat unexpectedly, the test results put my four top strengths as just the ones I’d choose for myself. Two thoughts about this: first, how did it do that? It was literally 92% random selections. Second: why did I spend all that time taking a survey when I already knew what the results would be?! I could have looked at this chart and told you most of my strengths would lie in the “Strategic Thinking” block, and four of my five “strengths” were in that quadrant. The only outlier was one in executing: I have a “restorative” strength — I like to fix stuff and solve problems. No, I don’t. I don’t at all. I prefer to think things through carefully and avoid the damn problems in the first place. That’s my priority.

This is one of the biggest contemporary frustrations with teaching, and it seems to be nationwide: the powers that be require us to waste so much time on just such things as today’s nonsense.