An acquaintance posted a video on social media about the rapture — one of the most bizarre ideas in all of Evangalicism.

He begins thusly:

The rapture of the church is when Jesus comes for his church the second coming is when Jesus comes with his church. The rapture of the church happens when he appears in the clouds of heaven he does not come to earth we go up to meet him. The dead in Christ rise first we which are alive and reign shall be instantly caught up to be with the lord in the air and we go to heaven.

The first thing that happens is the judgment seat of Christ. Paul said we must all appear before the judgment seat of Christ to give an account of the deeds that have been done in our body whether they are good or whether they are bad. Our works are going to be tried by fire so that our lives in its essence will be given purity as we enter our eternal life. Every person is going to stand here people say well uh you’re already in heaven it’s not a matter of if you’re going to be in heaven and on it’s a matter that you are going to give an account to God for what you have done and what you fail to do. The gap that exists between what you could have been and not were not because you did not use the opportunities god blessed you. You are still going to be in heaven but you are going to receive a reward in heaven based on what you did on this earth where there are going to be five different crowns that you can receive. You’ll receive a white robe and we are going to receive the mansions. We are going to be there for a period of seven years and there will be the marriage supper of the lamb.

While we’re in heaven seven years there will appear on this earth the antichrist and he’s going to set up a government of ten — ten men who will lead groups of nations — that will be complete dictators on the face of the earth. Every commercial exchange shall be recorded. You cannot do anything without his permission. He will start out making a treaty with the state of Israel that’s for seven years. He will break that treaty in three and a half years.

In this seven-year period there will be six seals, seven seals, seven trumpets, and seven vials: 21 supernatural acts of judgment that are coming on this earth. Just one of those acts will be whenever angels are released to destroy a third of the earth’s population in a day what’s going to happen on this earth will be hell on

earth and we the bride of christ are going to be in heaven.People teaching that we are going to go through that just simply biblically misinformed.

This claim that dissenters of this view are “simply biblically misinformed” would carry a lot more weight if there was anything in the Bible that actually explained things like he does in the video. If we could turn to Hypothetical Book of the Bible chapter x beginning in verse y and find what is quoted above, perhaps in more flowery language, perhaps a little more poetic, I might think the guy has a point here. However, the Bible says nothing about this. Instead, we find passages describing hallucinations of multi-headed beasts rising from the sea and then these people interpret it to mean this silliness. They explain it as if they are simply describing something they see in front of them or the process by which uranium-238 gets processed into uranium-235 (i.e., observable, confirmable, testable facts in our reality), but in fact, it’s just wild conjecture.

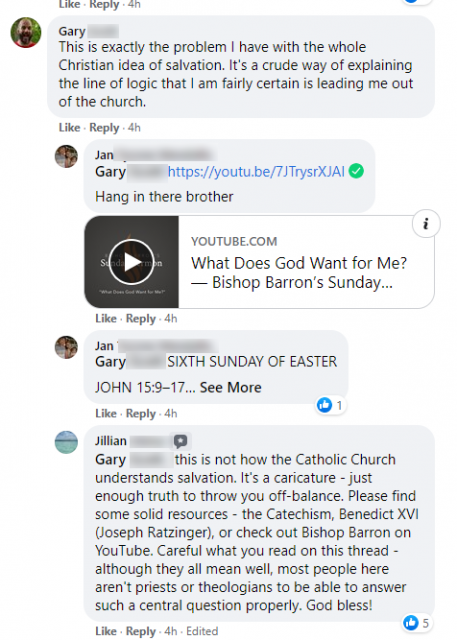

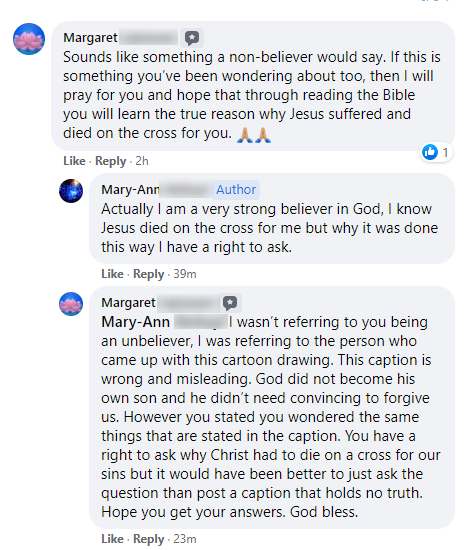

And then there are all the competing interpretations. The Catholics, for example, have their own interpretation, strangely (for such a superstitious belief system) less based in wild conjecture:

The aim of the Apocalypse, the most difficult book of the Bible to interpret, is eminently practical. It contains a series of warnings addressed to people of all epochs, for it views from an eternal perspective the dangers, internal and external, which affect the Church in all epochs.

It’s sort of a handbook for spiritual growth, I guess. It’s not for the future, in other words; it’s for all time. That’s less crazy than suggesting that beasts coming out of the sea somehow represent contemporary events.

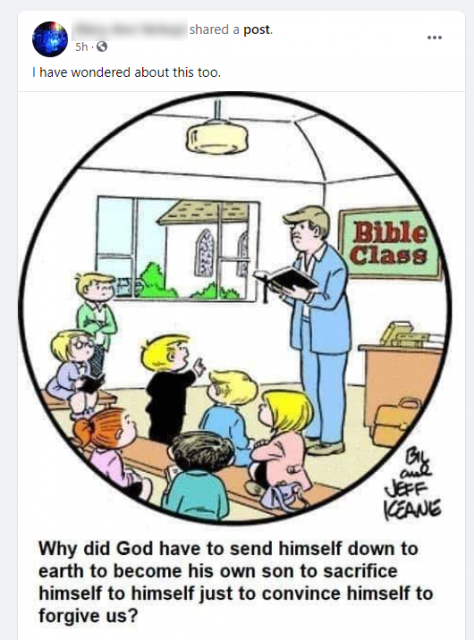

And there’s a meme that perfectly illustrates a central problem with this interpretation:

Today’s reading with Fr. Mike included Numbers 15, and if I’m writing about it, you can probably guess why: more brutality. Verses 32 through 36 read

Today’s reading with Fr. Mike included Numbers 15, and if I’m writing about it, you can probably guess why: more brutality. Verses 32 through 36 read