Poland produces a revolution every five hundred years, and it’s always the same revolution: a man comes along and challenges the way we all look at the universe, challenges us to stop thinking we’re the center of the universe and that all things circle around us.

Poland produces a revolution every five hundred years, and it’s always the same revolution: a man comes along and challenges the way we all look at the universe, challenges us to stop thinking we’re the center of the universe and that all things circle around us.

Copernicus was the first to suggest that the Earth was not the center of the universe. He dethroned the heady notion that literally everything revolved around us, and modern science has pushed us to the point of virtual cosmic insignificance.

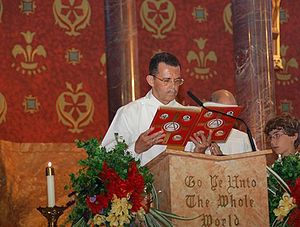

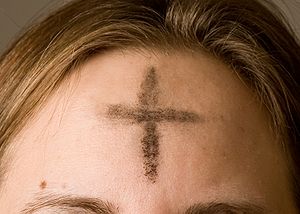

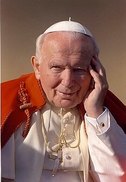

Karol Wojtyla, with his famous words, “Do not be afraid,” challenged us to stop thinking of ourselves as the center of our own worlds. Love is the greatest of all these, said Saint Paul, and John Paul, in his insistence on the universal recognition of human dignity and freedom, showed how to put that into practice.

“Nie lekajcie sie!”

Don’t be afraid.

Fear not.

How can we not fear? Look at the world, and the injustice that hounds it, and it seems the only thing we can do is be afraid. How can that possibly work? Perhaps when we start following John Paul’s example and love others more than ourselves, we will stop fear. After all, what is fear? It’s fear of what will happen to me. When I start loving others more, I stop thinking of my self so much, and I stop fearing.

John Paul in that sense was a Copernicus for the soul.

Excerpted from a post dated 5 April 2005.