The third day I was in Poland, I encountered my first Corpus Christi procession.

Suddenly the bells began ringing and eventually I caught sight of a procession coming around from behind the church. Choir boys were dinging small bells and behind them was a procession of relics. A little behind that was the priest, walking under a canopy supported by six men, preceded by a young priest waving an incense burner. The head priest was holding a staff with a gold sun in front of his face — he was led by the arms, for he certainly couldn’t see where he was going. Behind the priest was a group of loosely organized lay-persons, singing a capella. The woman beside me knelt as the group went by.

Not having had much exposure to Catholicism, I’d assumed that the doctrine of transubstantiation was a relic of the past. (I also didn’t know what a monstrance is, but that’s really not the point.) But it is a belief alive and well among more traditionally-minded Catholics, which used to be, I think, much more of a universal description of Poland than it is now. I was in Radom when I first encountered Corpus Christi, and while Radom is no Warsaw, it’s not some backwater village, virtually cut off from the urban realities of contemporary life. Still, when the Corpus Christi passed by, even those not participating knelt.

I used to wonder how many of those kneeling really believed in the doctrine of transubstantiation, that the host really is the body of Christ (hence Corpus Christi). It’s a strikingly literal interpretation of the Bible. When Jesus said, “This is my body,” he meant it.

52 Then the Jews began to argue with one another, saying, “How can this man give us His flesh to eat?” 53 So Jesus said to them, “Truly, truly, I say to you, unless you eat the flesh of the Son of Man and drink His blood, you have no life in yourselves. 54 He who eats My flesh and drinks My blood has eternal life, and I will raise him up on the last day. 55 For My flesh is true food, and My blood is true drink. 56 He who eats My flesh and drinks My blood abides in Me, and I in him. 57 As the living Father sent Me, and I live because of the Father, so he who eats Me, he also will live because of Me. 58 This is the bread which came down out of heaven; not as the fathers ate and died; he who eats this bread will live forever.” (John 6:52-58)

The argument is simple: if Jesus was only being metaphorical here, he would have said so. This is why Catholics kneel so much: it’s a belief that we are in the physical presence of Christ, and if that’s the case, kneeling is the logical response.

And so in predominately Catholic countries, on Corpus Christi, when the procession passes by with the glorified body of Christ in the monstrance, the usual reaction is to kneel. Or it was.

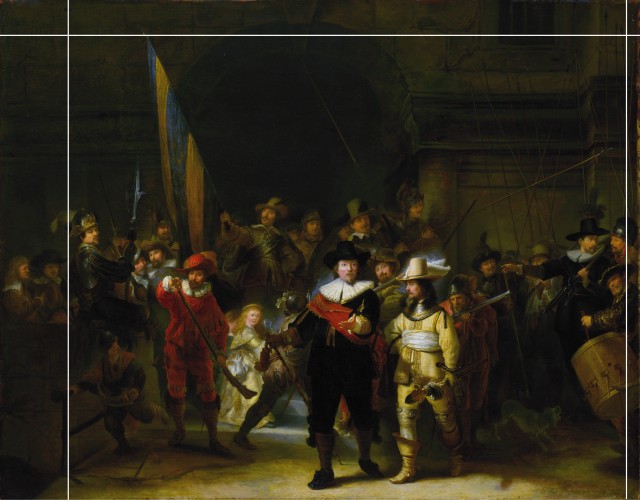

This shot comes from a Corpus Christi procession in Warsaw earlier this month. Two things are striking: the first is the rainbow in the background, a sign of growing tolerance toward homosexuality in Poland. The second is what really caught my eye, though: the folks in the front, enjoying an afternoon at the cafe, appear to be completely oblivious to what’s going on behind them. We can interpret this a couple of ways:

- No one at the cafe has noticed that there is a Corpus Christi procession passing by.

- No one at the cafe cares that there is a Corpus Christi procession passing by.

The first reason seems unlikely, but we can construct an argument: It happens so often, throughout the country on Boze Cialo (“Corpus Christi” in Polish) that perhaps it’s just common place to them, and they just really don’t think about it. Still, enough people are facing the procession to make this unlikely.

The second reason, to me, is quite sad. It’s not that I’m worried about the de-Catholic-sizing of Poland. I am, and I think it’s a great but inevitable tragedy. The Catholic faith has been the social glue that held Poland together for centuries, and it’s gradually weakening effect suggests a gradually weakening sense of cultural identity. Certainly there’s a lot about the Polish Catholic church that is, quite honestly, horrendous, but babies and bathwater come to mind in such a case.

What’s really depressing about the picture is the fact that this group of young people doesn’t even see it as important to show respect to those participating in the procession. Sure, they clearly don’t believe in the faith once delivered, but showing respect to others beliefs just seems like a sign of maturity that I see as lacking in contemporary society, and clearly it’s spread to the east as well.

Then there’s the irony of the caption: Wszystko jest inne niz 10 lat temu. Boze Cialo jest tutaj inne. Fotografia jest inna – zdjecie zostalo zrobione telefonem komórkowym. “Everything is different than it was ten years ago. Corpus Christi is different. Photography is different: the picture was taken with a cell phone.” So Szymczuk himself was at the cafe, but ironically he stood, perhaps out of respect but more likely to better frame the image.

I showed the picture to K, who was not surprised — nor was I, to be honest. “Things are changing in Poland,” she said (translating — no need to put the original Polish). “Everyone in Poland is Catholic by birth, but fewer and fewer actually believe.”

Again, it’s not the lack of belief that’s troublesome: it’s the lack of respect.

That seems to be the defining characteristic of this new millennium. It’s slowly becoming the case that I’m more surprised when a student is consistently respectful — to me and to peers — throughout the year than I am when someone is consistently disrespectful. And where does this come from? I think a song the DJ played today during the eighth-grade day celebration

I was mercifully unfamiliar with the number, but plugging “watch me song” revealed that it’s someone who goes by the name Silento. The lyrics are fairly typical of today’s music:

Now watch me whip (kill it!)

Now watch me nae nae (okay!)

Now watch me whip whip

Watch me nae nae (want me do it?)Now watch me whip (kill it!)

Watch me nae nae (okay!)

Now watch me whip whip

Watch me nae nae (can you do it?)Now watch me

Ooh watch me, watch me

Ooh watch me, watch me

Ooh watch me, watch me

Ooh ooh ooh oohOoh watch me, watch me

Ooh watch me, watch me

Ooh watch me, watch me

Ooh ooh ooh oohDo the stanky leg, do the stanky leg

Do the stanky leg, do the stanky leg

Do the stanky leg, do the stanky leg

Do the stanky leg, do the stanky legNow break your legs

Break your legs

Tell ’em “break your legs”

Break your legsNow break your legs

Break your legs

Now break your legs

Break your legsNow watch me (bop bop bop bop bop bop bop bop)

Now watch me (bop bop bop bop bop bop bop bop)Now watch me whip (kill it!)

Now watch me nae nae (okay!)

Now watch me whip whip

Watch me nae nae (want me do it?)Now watch me whip (kill it!)

Watch me nae nae (okay!)

Now watch me whip whip

Watch me nae nae (can you do it?)Now watch me

Ooh watch me, watch me

Ooh watch me, watch me

Ooh watch me, watch me

Ooh ooh ooh oohOoh watch me, watch me

Ooh watch me, watch me

Ooh watch me, watch me

Ooh ooh ooh oohNow watch me you

Now watch superman

Now watch me you

Now watch superman

Now watch me you

Now watch superman

Now watch me you

Now watch supermanNow watch me duff, duff, duff, duff, duff, duff, duff, duff (Hold on)

Now watch me duff, duff, duff, duff, duff, duff, duff, duff, duffNow watch me (bop bop bop bop bop bop bop bop)

Now watch me (bop bop bop bop bop bop bop bop)Now watch me whip (kill it!)

Now watch me nae nae (okay!)

Now watch me whip whip

Watch me nae nae (want me do it?)Now watch me whip (kill it!)

Watch me nae nae (okay!)

Now watch me whip whip

Watch me nae nae (Can you do it?)Now watch me

Ooh watch me, watch me

Ooh watch me, watch me

Ooh watch me, watch me

Ooh ooh ooh oohOoh watch me, watch me

Ooh watch me, watch me

Ooh watch me, watch me

Ooh ooh ooh ooh

This is the “watch me” generation, to the point that a current hit is literally just the words “Watch me!” And this is why I see this as an issue of maturity: who typically runs around saying, “Watch me!”? Now, of course, we have seemingly countless ways to get people to watch us in the form of the endless stream of social media we’re surrounded with. The point is simple: while we’ve always been a narcissistic species, technology has made it easier never to grow out of that.

He says on his blog.

No, watch me!

The problem of evil for many is the single most convincing argument for an atheistic stance. Dr. Peter Kreeft, of Boston College,

The problem of evil for many is the single most convincing argument for an atheistic stance. Dr. Peter Kreeft, of Boston College,