A curious story appeared in Newsweek the other day that highlights some of the quirks of Catholicism. Apparently, a priest there has been saying the wrong words during baptisms, which makes the baptisms invalid:

A priest with over two decades’ worth of service to multiple congregations has resigned “with a heavy heart” in the wake of revelations that he incorrectly performed baptisms.

Father Andres Arango, who most recently served in the Roman Catholic Diocese of Phoenix, Arizona, was found to have used the wrong phrasing.

When performing the sacrament, Arango would say, “We baptize you in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit.”

However, as the Vatican’s Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith made the diocese aware, the use of the word “we” made the baptisms “invalid.” Instead, Arango was supposed to use the phrase “I baptize” rather than “we baptize.” (Source)

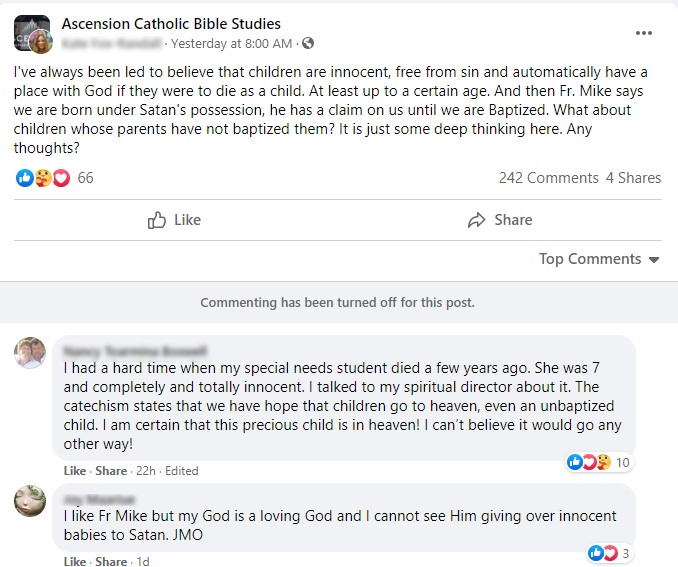

So all these families have been taking their children to the priest to say the right words in order to remove the effects of the apple curse and safeguard their children from the horrors of hell, and this guy has been saying the wrong words! According to Catholic teaching, if they’re not validly baptized, they’re not saved. If they died still a child, then they go to limbo heaven — I forgot, the Catholic church changed that teaching when enough people protested that the idea of infants going to limbo for eternity was unconscionable. (Does this mean that all the infants in limbo never were in limbo, or did they get a “Get out of limbo free” card?)

For the poor schmucks who made it to adulthood and thought they were freed of the effects of the talking-snake-induced apple curse, it’s another story. These folks died in the assurance of heaven only to awaken in the next life to the surprise of, well, not just their lives but of eternity.

“Um, excuse me, I think there’s been some kind of mistake,” they shriek, doing their best to maintain some kind of professional decorum.

“No, no mistake,” the demon idly pulling their intestines out and wrapping them around its forefinger says, almost sounding bored.

“Yes, I think there was. You see, I was baptized.”

The succubus pauses for a moment, tightens the ringlets of intestine just a bit, yawns and says, “No, I’m afraid you weren’t. You see, Father Arango said ‘we baptize you’ when all decent priests know the correct words are ‘I baptize you.’ A simple clerical error, to be sure, but nonetheless, an error.”

“But, but!”

The demon becomes irate: “Now look here — we don’t make the rules about these or those magic words. We’re just as bound to the formalities as you are.” He gives a good tug, dislodging the large intestines. “You’d have to take that up with God.”

“Where is he?”

“Not here,” giggles the tormentor…

All joking aside, there are lot of people now unnecessarily mentally tortured with the thought that their loved one is in fact in hell because of a priest’s mistake. Just how many people might be going through this?

Katie Burke, a spokesperson for the Diocese of Phoenix, told Newsweek that while the diocese has no exact number of invalid baptisms Arango performed, the number is “in the thousands.”

Thomas Olmsted, bishop of the Diocese of Phoenix, wrote a January 14 letter to his congregation informing them of the invalid baptisms. He said it is his responsibility to be “vigilant over the celebration of the sacraments,” adding that it is “my duty to ensure that the sacraments are conferred in a manner” consistent with the Gospel and the tradition’s requirements.

I guess Father Arango should have realized the importance of using the proper words…