Dear Terrence,

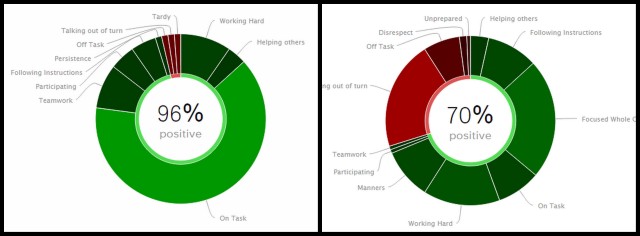

![]() Today you asked me a question that I’ve never heard you ask before: “Mr. S, what’s my Dojo percentage.” You’ve always insisted that Class Dojo is a waste of time and a generally stupid idea, and although I’ve never given up trying to convince you of its value, I never really thought you’d come around and see it for what it is: a powerful tool for monitoring and controlling your behavior. After all, everyone is keeping points on us in their heads for all the good and bad things we do. It’s called a reputation. But at least with Dojo, you get an idea of where your strengths and weaknesses are. Anyway, your question caught me off guard, because I really didn’t know. I had to check. And that was a good thing, because in the past, I could have likely guessed it without looking: “No more than 30%, I’d say.”

Today you asked me a question that I’ve never heard you ask before: “Mr. S, what’s my Dojo percentage.” You’ve always insisted that Class Dojo is a waste of time and a generally stupid idea, and although I’ve never given up trying to convince you of its value, I never really thought you’d come around and see it for what it is: a powerful tool for monitoring and controlling your behavior. After all, everyone is keeping points on us in their heads for all the good and bad things we do. It’s called a reputation. But at least with Dojo, you get an idea of where your strengths and weaknesses are. Anyway, your question caught me off guard, because I really didn’t know. I had to check. And that was a good thing, because in the past, I could have likely guessed it without looking: “No more than 30%, I’d say.”

You and I have had our issues this year, and at least once you’ve stormed out of class insisting that you have to get your schedule changed because you’re sure I’m out to get you. I assure you, I’m not: your behavior, though, sometimes seems like it is, which is why I think Class Dojo could be such a powerful tool for you. It could help you see your weaknesses (talking out of turn) and help you build on your strengths (helping others).

But you’ve made a turn around — at least your behavior of the last few days indicates that. So I was particularly pleased when I looked down at my phone and saw you were at 83% for the week.

Keep up the good work,

Your Teacher

And at that moment, young man, you sealed your fate. Previously, you’d simply been disrespecting me and my authority. But mocking the school-wide discipline program, you disrespected the entire school, the entire administration, and the entire teaching staff that came up with a school-wide plan to help you and students like you change some of the damaging behaviors you and students like you so clearly and brazenly exhibit. These are behaviors that will destroy your future if you do not make a serious attempt to change them, and our school discipline plan is intended to help prevent that, to help you see in an on-going basis the negative (and positive) behaviors you’re showing. And so it is not intended to scare or frighten or even punish: it’s intended to help. But you showed that you don’t want help, that you’re set the way you are, that you see a bright future with your behaviors. Ironically, it was that very short-sightedness that we’re trying to help you correct.

And at that moment, young man, you sealed your fate. Previously, you’d simply been disrespecting me and my authority. But mocking the school-wide discipline program, you disrespected the entire school, the entire administration, and the entire teaching staff that came up with a school-wide plan to help you and students like you change some of the damaging behaviors you and students like you so clearly and brazenly exhibit. These are behaviors that will destroy your future if you do not make a serious attempt to change them, and our school discipline plan is intended to help prevent that, to help you see in an on-going basis the negative (and positive) behaviors you’re showing. And so it is not intended to scare or frighten or even punish: it’s intended to help. But you showed that you don’t want help, that you’re set the way you are, that you see a bright future with your behaviors. Ironically, it was that very short-sightedness that we’re trying to help you correct.