This content is private.

at risk

Chess Claims

Every now and then, a student will challenge me to a chess game with much braggadocio and bravado.

“I’m going to beat you so bad, Mr. Scott!” comes the claim. “You don’t stand a chance.”

My response is usually simple: “Perhaps.” There are plenty of thirteen-year-old chess players in the world (probably in the county) who could, indeed, thrash me. When facing an opponent for the first time, I prefer humility. Usually.

What I was thinking, though, was anything but humble: “Perhaps. But remember, young one, I have worked with you for quite some time now. I know how you think. I know your critical thinking abilities. I know how much patience you have (or in this case, don’t have). I know how easily (or not) you make connections between seemingly disparate passages of the text. I know how well you infer. Very strong chess players do all these things better than the average person; you do most of these at about an average (or even below average) level. Also, to beat me, you’ll need to know chess theory better than I do, which requires study and focus — two things you don’t always excel at. Therefore, taking all of this into consideration, it’s highly unlikely that you will beat me.”

Now, thinking all these things, I often just play along with the trash talk: “Buddy, I’m going to kick you so hard your grandmother is going to feel it.” The most brutal trash talk I do is when, after a couple of moves, I just give the player my queen. “I won’t be needing that.” Among those who have a basic understanding of chess, this always elicits hoots and laughs. One student might run over to someone not watching the game and recount excitedly what I just did.

I thought about that today as students in my last period class struggled mightily with making claims for an argumentative writing assignment with which we’re concluding the semester. I thought I’d set everything up perfectly for them to see some connections that would lead to good claims. We were annotating the text for things illustrating the narrator’s family’s poverty and the acts of kindness they perform and in turn receive. I made sure students saw two passages:

- We were one of the last families to leave because Papa felt obligated to stay until the rancher’s cotton had all been picked, even though other farmers had better crops. Papa thought it was the right thing to do; after all, the rancher had let us live in his cabin free while we worked for him.

- She made up a story and told the butcher the bones were for the dog. The butcher must have known the bones were for us and not for the dog because he left more and more pieces of meat on the bones each time Mama went back.

Here we have two acts of kindness that directly contribute to the family’s survival. Yet none of the students could make the connections and inferences necessary to come up with a simple claim about this: “The family receives basic needs from the actions of others.”

The co-teacher in the class, seeing the same problem, started searching online for some sentence stems to help them with their claims. When working with struggling students, sentence stems (also known as frames) help students orient their thinking and direct their writing.

“Since claims can be so varied,” I told her, “I doubt you’ll find much.” She’s a great special education teacher and a real advocate for all students: she didn’t give up. Still, she found nothing.

“I just don’t know how to teach these kids such basic critical thinking skills,” I said. I’ve tried logic puzzles and similar ideas, but I’m just not good at that. I feel that’s teaching skills (inferring, categorizing, comparing/contrasting) that most kids have learned years ago. It’s something an elementary teacher would be trained to teach. Not someone who studied secondary education.

It’s from classes like this that the “I’m going to beat you badly!” chess claims emerge. One such kid kept bragging while I set up pieces, and he put his class materials away. He sat down across from me and said, “Okay, so how do you play this game?”

Absent

If any of my colleagues ever suggested — or simply thought (then how would I know?) — that they were more productive a given day because I wasn’t there, I would feel such shame that it might be difficult to show my face again among those folks. I would reflect on my behavior, on what I’d always considered my contributions, and I would likely realize that I shouldn’t have simply been second-guessing myself; I would realize I’d had a completely false self-image.

Today, several students were absent, with most of them were suspended. The types that are likely to get suspended are the types that are likely to disrupt class, and so today, two classes that generally leave me wondering about my decision to stay in education were absolute pleasures. They were productive, polite, focused. They were unlike they’d been in a long time, if ever. (Is it really only September? Are we really only in the second half of the first quarter?! I feel so tired of it all that everything in me screams that it must be March.)

What if I tell these students that? How would that conversation go? I think we all know: they would be indifferent. At least one of the students admitted openly that he is disruptive because he knows it annoys other students, and he likes to annoy other students.

Several of them will be back tomorrow — will it be business as usual? No. I’ve seen what we can accomplish: if they are unwilling to cooperate, I will do what is necessary to protect the education of all the other students.

Tuesday School Thoughts

On the one hand, I’m responsible for teaching them to read and write better. That’s my bottom-line assignment at work. Traditionally, that’s all a teacher has ever been expected to do: teach the course material.

Yet some of my students fall under the rubric “at-risk” in one form or another. They can’t stay focused for more than five minutes (at best) or five seconds (literally, at worst). They can’t keep up with their materials until the next day (at best) or the next minute (at worst). They can’t accept “no” as an answer, and they take everything personally and turn things into battles that have no business being fights to begin with. They come in without materials — no pencil, no paper, no nothing.

These are the kids whose behavior, quite honestly, disrupts the learning of anyone and everyone else in the room. They are black holes for attention: their every second is a new event horizon to resist. Interactions with them can be quicksand, pulling everyone in and restricting movement completely. Working with them for five minutes can be utterly exhausting; working with them for a whole class period can have one questioning one’s sanity.

Yet what option do we have as teachers? No one else is teaching these kids (only a few — perhaps 7-10%, and not even that many who are so demanding and high-maintenance) these skills. At least it seems no one else is teaching them the skills. And someone has to teach these kids the basics of how to interact successfully with the world.

But it’s so exhausting…

Socratic Seminar

They’re tough classes at times, filled with a mix of students with mixed motivations and mixed ability levels. And all of this manifests itself in students’ behavior: several students are focused and hardworking while a few are determined to gain attention by any means necessary, with the vast majority simply there, engaged sometimes, bored and checked out others.

But there’s one activity that always gets good results: Socratic Seminars.

If I could have these on a biweekly basis, I think I could have a serious motivator for the students. So why don’t I do it? That’s a very good question, indeed. I shall be working them into plans one way or another on a much more regular basis based on how well students engaged in their first seminar of the year.

And I haven’t even done one with my honors students yet…

Perception

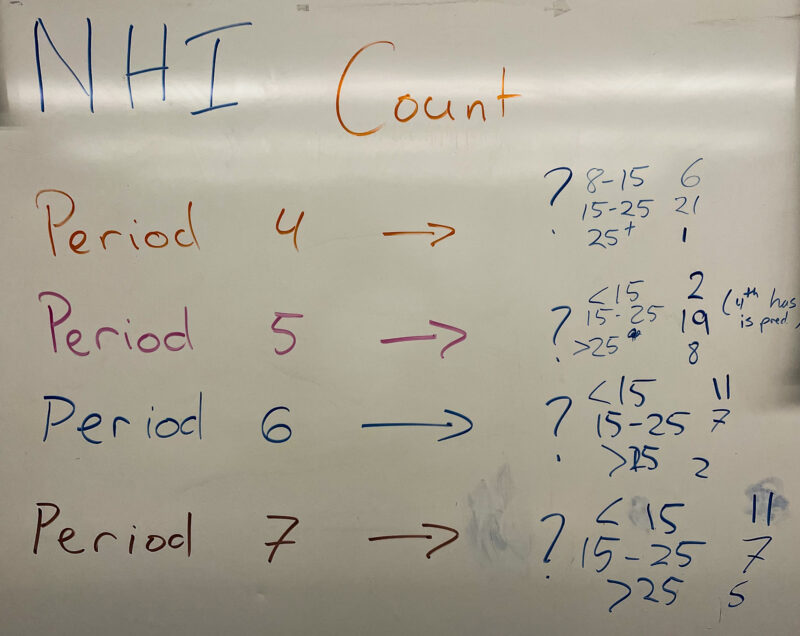

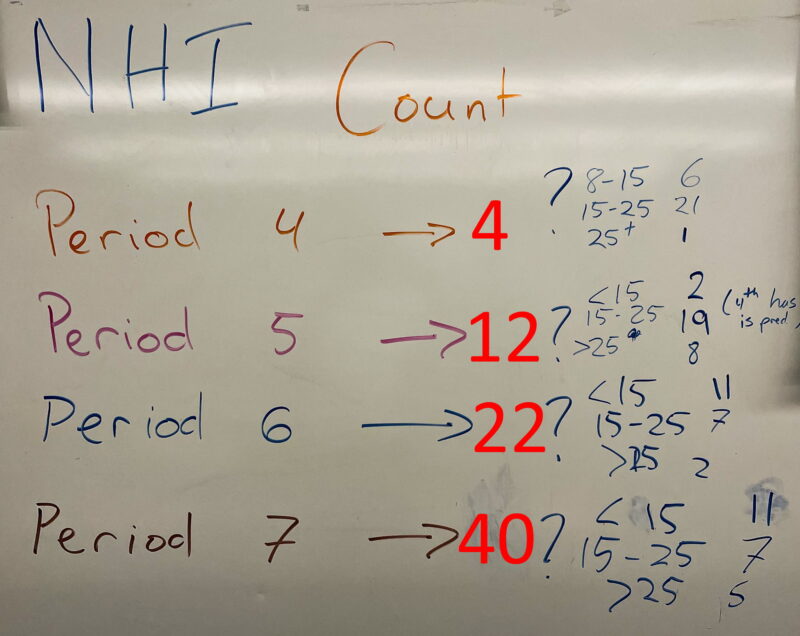

We have an epidemic of NHIs in the eighth grade. NHI is the code we enter for a graded assignment the student failed to turn in. Not Handed In.

I had a talk with my classes about the issue. On Thursday, I had students in each class guess the number of NHIs in their class for English. There were three options:

- Fewer than 15

- Between 15 and 25

- More than 25

The two English I classes were certain they had between 15 and 25 per class. The two English 8 classes were certain they had fewer than 15.

The results for all classes were the exact opposite of what they expected.

The English 8 students refer to the English I (high school English) classes as “the smart kids’ class.”

“They’re not the smart kids class,” I always reply, but Friday, when I revealed the results, I added, “They’re simply the do-the-work kids class.”

Fluke?

I was so excited about how well things went with my toughest class yesterday: we did such good and focused work, though, that I should have expected today. Frustrating all around.

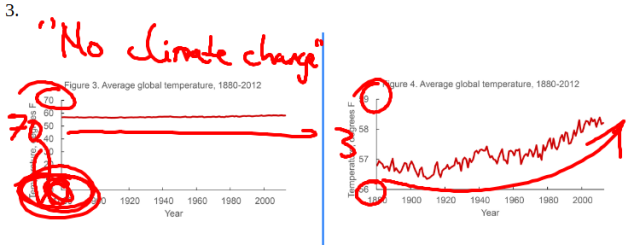

During the bell ringer, when we were going over some of their work, trying to get a student to say that the highest value on the Y axis of a graph (we’re reading a cross-curricular text about deception in graphing) was 70. Even when I pointed to it. Even when I said, “The first number is seven.” Even when I added, “The second number is zero.” Even when I said “70.” Even when I said, “Say ’70.'”

Later in the lesson, when we were going over how to do something, I did the first half of the work for them — for all intents and purposes — in the name of modeling, even though we should be past modeling now. Be all that as it may, some of the kids didn’t even make use of the modeling — and really all they had to do is copy what we came up with as a class.

Every class has tough days, I guess. But they’re even tougher when the happen on the heels of a great day.

Mindfulness

I tried something today, sort of spur of the moment, with one of my more struggling classes. It’s filled with impulsive students who are generally very sweet (at least toward me) but can be very chatty. Very focused on other things than the work at hand. So before we started our main part of the day’s lesson, I had the kids do a little mindfulness work.

“Close your eyes,” I told them.

“Did they trust you enough to close their eyes?” my principal asked when I was telling him about the experience later in the day.

“Yes, they did,” I replied, thinking of what his question suggested about the relationship I have with the kids already.

“Close your eyes,” I said, a few times. There were some stragglers. Some were still focused on something else. “Just close your eyes and breath slowly for a moment.” I led them through some slow breathing, then had them visualize the work we were about to do, seeing themselves working in a focused manner and meeting success instead of frustration.

They opened their eyes, we began the main part of today’s lesson, and they had the most successful day we’ve had so far.

Growth

It’s that time of year: my students are writing their letters to next year’s students. The English 8 kids wrote them last Friday; English I will be writing them in a couple of weeks.

The guidelines are simple:

- Provide advice for rising eight-graders

- Show off how well you can write now.

To achieve the second goal, I only allow students one class period to write the letters. The results could theoretically be a little better for the English 8 students if I gave them more time, but part of the charm in the whole exercise is watching next year’s students’ shock when I tell them at the letters they’re reading are in fact first and only drafts.

One young lady’s letter demonstrated so wonderfully how much she’d grown as a person from the beginning of the year. J, at the start of the year, was one of the most worrying students: her behavior was often disruptive; she was often disrespectful when teachers called her on her behavior; she rarely did any work, and what she did was not turned in or handed in still incomplete.

Yet over the course of the school year, she’s calmed down, learned that butting heads with teachers is counterproductive, and begun doing her work (then doing her best). Her grade has gone from a 62 (just barely passing) to a 84, just six points shy of an A.

One paragraph of her letter reads:

How to stay out of trouble in the 8th grade? Staying out of trouble in the 8th grade is probably one of the most important things you can do. One thing you can do to prevent getting in trouble is to minimize your circle and stop posting things on social media. People take a lot of things to social media and the drama leads into school so now it’s the school’s problem and once you post something on social media there’s literally no going back. It’s there forever. Having a lot of friends can cause you to get into a lot of stuff because once one of your friends is beefing with one another they are going to bring you into it because they want you to choose one or the other. My advice to you as a 8th grader right now is to never trust a soul, follow the right path and take it slow, that’s how you can be successful in the 8th grade.

There’s a certain cynicism in that conclusion, but perhaps it’s not entirely awful advice.

Wednesday in Class

That fifth period can be a tough group of kids. They sometimes disregard what’s going on in class to have a little private conversation that is not at all private because of the number of participants and the volume of their voices. They sometimes ignore simple instructions. A few of them are capable of being truly disrespectful to other students, to me, and by proxy, to themselves.

Yet by and large, they’re a great group of kids. They’re just typical 14-year-olds, many of whom come from less-than-perfect situations and have developed less-than-perfect habits. In my teaching career, there have only been a handful of students that, as humans, I didn’t like, I just didn’t trust. In almost 25 years of teaching perhaps four or five such kids. There are no such kids in this group.

But they can be tiring.

These final weeks of school, we’re going through The Diary of Anne Frank. Why do such an important piece in the waning, testing-ladened final quarter of the year? That’s when the district requires it. It might be a good thing, though, because these kids are more engaged now than they’ve been all year: more focused, more involved, more eager in their participation.

Plopped down in the middle of this is L, a young man from Mexico who speaks not a word of English. Not a word. Well, no, that’s not true: he spoke not a word of English when he arrived last week. He’s already picked up quite a bit. And today, he was able to follow along with the play, even though he didn’t understand 95% of what the kids were saying.

“Where do you think we are?” I’d ask through my phone using Google Translate. He’d point to where we were — each time, dead on. “Great!” I’d say. His smile was ear to ear.

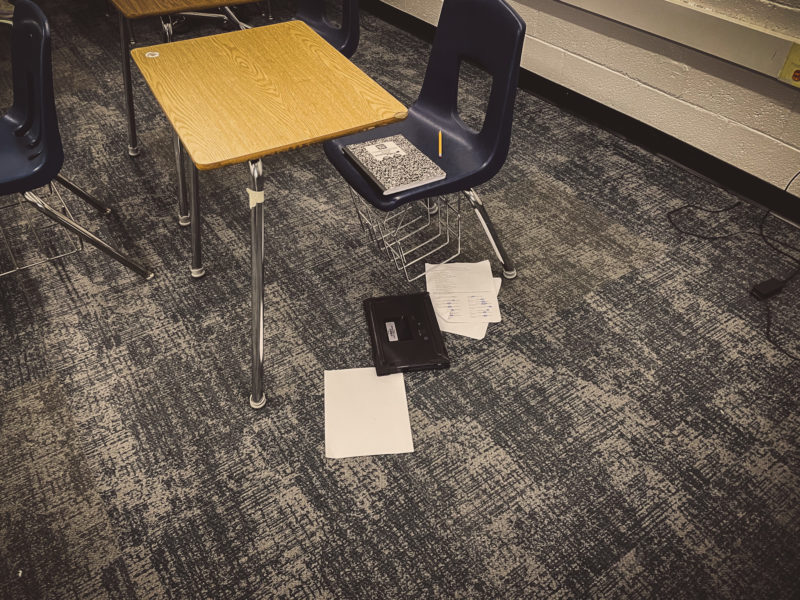

Left Behind

“Pick it up!” she yelled. We were at the end of class when A, who’s always a bit of an immature prankster, pushed K’s materials off her desk. K, who has issues with impulse control (i.e., she’s a chronic disrupter) doesn’t like when her world is disrupted, and she grows verbally violent when it happens. A was walking away smiling, which of course led to K feeling even more aggrieved. “I said,” she began, taking a deep breath, “pick it up!” He walked out the door. She walked out the door herself — not to accost him in the hallway, not to get help from an adult. No — she declared as she walked out, “Well, I ain’t pickin’ it up.” Bear in mind: these were her materials. She literally walked into her next class without her materials, thinking she was perfectly justified in doing so.

I picked her materials up and stowed them in my cabinet. Part of me was justifying it with the thought that it would teach her a little lesson; part of me did it, I think, just to irritate her further. That is, I’ll readily admit, somewhat childish, but at the time, I wasn’t thinking in terms of irritating her. I wanted her to go through the last two periods of the day without her materials to provide an object lesson to her: “Do you realize how many of your problems in school are of your own creation?” I’d planned on asking her when she got her materials back. “You had to go through two periods explaining why you didn’t have your materials, and I guarantee all your teachers responded the same way: ‘That’s your own fault.'”

Ten minutes into the next period, she was knocking at my door. A student let her in. She stormed back to her seat, and discovering her materials were missing, turned and yelled to the whole class, “Where’s my stuff!?!” She proceeded to rant for a while, completely disrupting what we were doing, but I just let her rant for a while. After about thirty seconds, I said, “K, I need you to go back to your class now.”

“But where’s my stuff?!?”

“I need you to go back to class now.”

“But I’ve got to get my stuff.”

“I need you to go back to class now.”

“I have to have my stuff. Where’s my stuff?”

“I need you to go back to class now.”

Her teacher came to the door, a puzzled look on his face.

“Mr. A says I need my stuff.”

“I need you to go back to class now.” I’ve found that the best way to deal with such situations is just to be a broken record, and as it always does, it worked: she huffed and started out of the room, then turned and walked over to a friend and started talking to her.

This is the kind of behavior teachers have to deal with every single day. Every almost single class. In some classes, every single minute.

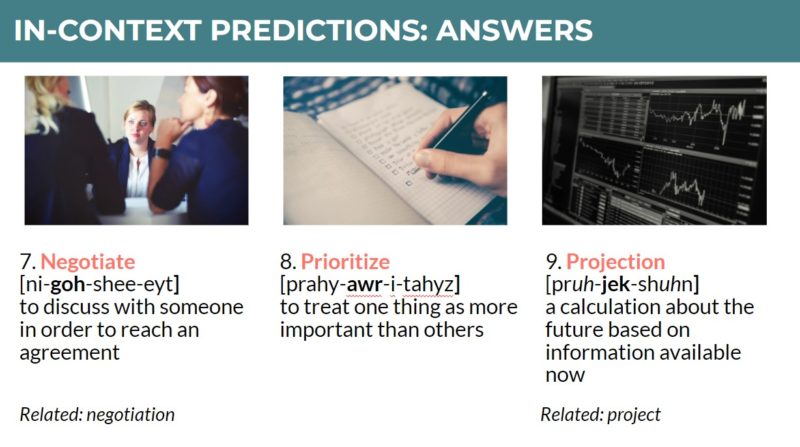

Negotiation

Going over some words in class today that might be new to some students (it was my remedial class), I started asking kids questions about the words.

“What might you prioritize as a student?”

“Your work!” someone responded. If only, young man, if only.

“What might I make projections about as a teacher?”

“Grades.” Yes, and if only you knew the projections — no, you probably do.

“With whom might you negotiate?”

“Your parents.” Of course.

“I don’t negotiate with my parents,” says one boy. “I do what I want.”

Bravado or inadvertent succint social commentary?

In Front of Them?

We’re working on a tricky standard in school in my on-level classes. They’ll have a TDA (text-dependent analysis) question as part of their year-end test, and it’s often a question about how some text develops some idea or other. It might even provide an excerpt and ask specifically how that passage contributes to this or that idea. It’s not a straightforward question, and while I’m not entirely sure it’s a useful question to pursue with kids who have difficulty reading at grade level, I am obliged to some degree or other to teach to the test. That’s what we’ve done the last couple of days. We worked through a text together and then figured out how to answer such a question. Today, students were working to do it on their own.

Part of the process, I taught them, is to take the main idea of the text and compare it with the passage the question wants us to analyze. “See what similarities they have, what differences. Think about the relationships between those.” Since the first multiple-choice comprehension question for our article “Why I Refuse To Say I ‘Fight’ My Disability” was “Which of the following statements best expresses a central idea of the article?” I knew we could save time in determining the main idea for ourselves. We evaluated the four possibilities and realized it was the first option: “Hitselberger’s disability is an important part of who she is, not an enemy that she needs to defeat.”

The analysis question didn’t deal with just one or two sentences; it dealt with the entire final third of the article. “How do paragraphs 5-14 contribute to the development of ideas in the text?” At first I thought, “Great, the kids will have to comb through nine paragraphs to find the answer.” Then I looked at the nine paragraphs. I didn’t have to look closely: the relationship is literally plastered throughout the passage.

I will say I fight ableism and prejudice.

I will say I fight lack of access, stigma and ignorance.

I will say I fight discrimination.

I will say I fight these things, because I do. These are battles to fight, and win. It is ableism, prejudice, lack of access, stigma, ignorance and discrimination that prevent me from having the same opportunities in life as my able-bodied brother and sister, not my cerebral palsy, my wheelchair or my inability to walk.

I will fight to make this world a better place for future generations of kids just like me.

I will fight to make sure they are never told or led to believe their bodies are a problem or something they must do battle against on a daily basis just to fit in.

I will fight to make sure those kids have the same opportunities as everybody else, and never believe everything would be better if they could just change who they are.

I will fight for a world where the mere presence of disability does not make you extraordinary. Where disabled children are taught to aspire to more than just existing, and where being disabled doesn’t mean you have to be 10 times better than everyone else just to be good enough.

I will fight for a world where we talk about living with and owning our disabled bodies rather than overcoming them.

I will fight for a better world, and a better future, because those things are worth fighting for, but I will not fight a war against myself.

So it’s simple, I thought. The main idea statement is “Hitselberger’s disability is an important part of who she is, not an enemy that she needs to defeat.” Every single paragraph of the passage begins with “I will fight.” It’s not terribly difficult to see the connection between “fight,” “enemy,” and “defeat.” So the main idea statement says that the author will not fight her disability while the passage gives a list of things the author will fight.

Most of them could not see it. I phrased it differently and rephrased it again. Many of them could still not see it.

I’ve been thinking about this all day, wondering what went wrong. Was it the presentation? I’d like to think I’d done a decent job scaffolding the learning: we’d practiced the very same thing with the very same question yesterday. The only difference was the text. Was it the students? Just as I’d like to think I wasn’t responsible, I’d like to think it wasn’t a question of student culpability because there are only two ways to explain it: they can’t do it, or they won’t do it. Neither one is appealing. Yet of all three options, I wonder if the truth isn’t hidden in one of them. It’s not a question of intelligence or reading ability; perhaps it’s just a question of critical thinking.

Little Steps

Dear Terrence,

I read your letter and felt it really needed a reply: you touch on a lot of issues that got me thinking, gave me hope, and honestly caused me to worry a bit.

You wrote that you “feel like people criticize [you] because of [your] past,” something which “hurts [you] to even try to change.”I don’t know what you thought I might have known about your past, but I knew nothing. I’m also fairly sure the other teachers on the team knew nothing about you. Yet we can all accurately guess about your past because of your present. I don’t mean to be offensive or blunt, but despite your desire to change, you still exhibit a lot of behaviors that draw negative attention to yourself. I don’t know about other teachers’ rooms, but I can describe some of the things in your behavior in my room that makes it pretty clear that you’ve had a rough past in school.

- You often blurt out things that you’re thinking, things that might not help the classroom atmosphere. Sometimes you say things that are genuinely insightful, but it’s still disruptive.

- You sometimes get up and move about the room for this or that reason without asking permission or seeming to notice that doing so would be an interruption. Sometimes this is to do something genuinely helpful, but it’s still disruptive.

- You put your head down when you get frustrated, and even when you’re not frustrated, you cover your face with your hands and completely disengage.

- When I correct you, you often quickly develop a negative, disrespectful attitude that comes out in your tone of voice and your body language.

You write that you want teachers to “just give [you] a chance and stop messing with [you],” but if a teacher is correcting these behaviors, she’s not “messing” with you. You must understand that some of your behaviors genuinely disrupt the class, and a teacher cannot continue teaching over disruption.

I do have some bad news, though: while no one is messing with you, you’ve made it clear what gets under your skin, and if a teacher wanted to mess with you, wanted to provoke you so that she could write you up, you’ve made it easy for that teacher (whom I hope you never meet) to do just that. You’ve made it clear what your buttons are, what gets you heated and easily leads to a disrespectful outburst. All a teacher would have to do is push just a little and BOOM! there you go, and there’s the excuse to write a referral. In that case, such a teacher would have played you, controlled you. I hope you never meet such a teacher, but it’s entirely possible. It’s also possible that a teacher who wouldn’t normally do that might, in a moment of frustrated weakness, do just that to “get some peace” for a while.

Fortunately, I have some good news, too: letters like yours make a teacher’s day. It gives us hope that perhaps we can help make a difference in students’ lives. I don’t know a single teacher—especially the teachers on our team—who won’t go out of his or her way to help a student who wants to change his/her behavior to do just that. However (and it’s a pretty big “however”), you have to show that you are really trying to make these changes. You have to show progress on a regular basis. Not big progress; not 180 degree changes overnight. But teachers need to see that you are serious about something like this. Otherwise, we’re left wondering if you’re just playing us. I’m sure you’re not, but it has been known to happen, and teachers tend to be a bit wary about that.

Here’s what I suggest you do if you really want to be a “changed man” as you so aptly called it. First, make sure you go to each teacher and say as much to him/her. Look the teacher in the eye; make sure your facial expression is pleasant; be sure not to let yourself be distracted by anything other students might be doing; then say what you said in the letter. “I’m trying to change, but I might slip into old habits. Please be patient with me as I try to make these changes in my life.” Second, make your strongest effort to change right then. Show the teacher you mean business. Show the teacher that you are not just talking the talk but you’re trying to walk the walk. Sit quietly; stay in your seat; keep your head out of your hands; make sure you don’t use a disrespectful tone of voice. Third, when you slip up (and you will: you’re trying to change some habits that you’ve had for a long time, I suspect), apologize. Sincerely. But not right then! If you do, the teacher is likely to think you’re just trying to disrupt further. Just smile as best you can and comply. After class, you can go to the teacher and say, “I really messed up. I appreciate your patience with me. I’ll do better next time.” Finally, make sure all your friends know what you’re up to. If you’re trying to be Mr. Thug or Mr. Cool Dude with them but Mr. Nice Guy with your teachers, you’ll get those roles mixed up and cause yourself more trouble. Be a leader: tell your friends, “Hey, I’m sick of hating school, sick of dreading school, sick of feeling like I’m wasting time. I’m going to make some changes in how I act, how I think, how I see myself and the world.” Be a leader: show other kids how to do it. They’ll follow your example, because everyone loves to see a “troubled-kid-straightens-everything-out” story. We love it, all of us.

Understand that I’ll do everything in my power to help you. I have some tricks I can teach you about making a good impression, keeping your impulses in check, and having a positive affect. (If you don’t know what that means, ask me: I’ll gladly explain.) But as I said earlier, I and all the other teachers have to see change immediately. Not enormous change, but change. Effort.

Reading

Tuesday Unknowns

Unknown 1

We had an online meeting tonight with a company that helps student-athletes navigate the challenge of getting an academic scholarship. It’s something that I have absolutely no firsthand knowledge and little to no general knowledge about. The question is, given the cost of the service (it’s not cheap by any stretch), just how much will this provide us in the long run. Its cost would certainly be justified if we ended up with major savings to L’s college costs through a scholarship to play volleyball. Yet if we just get nothing for it — no real offer, no real scholarship, no real hope — then it was obviously money poorly spent.

Unknown 2

We had a teacher workday today, and the day concluded with a presentation from a therapist about trauma and its effects on learning. It basically boiled down to, “Don’t be a dick and compound these at-risk kids’ issues by taking everything personally and letting that trigger you into a power struggle that damages the relationship.” That’s laudable, and certainly a very basic best practice for classroom management, but it got me thinking about how much we never know about our students in a given moment: what taught a kid to react this way to this stimulus, what’s going on in the kid’s head at the moment, how we’re contributing to it, what other social forces, unseen and unknown, are contributing at that moment due to peer pressure and the idea of lost face — the whole miasmic mess we find ourselves in when an at-risk student is in full panic mode. Not an excuse for disregarding the processes we went over today. Far from it — a full admission to their basic necessity. Yet it still leaves me feeling a bit like Sisyphus.

Unknown 3

One of our final renovations on our house will begin tomorrow: the guest bathroom will get a complete makeover.

Heaven knows it needs it. In a lot of ways, it was always the room most in need of renovation. Ugly subway tiles on the counter, some god-awful trim around the sink, old toilet — it was all awful.

Was?! It is awful. It has been awful for years. And tomorrow, we start renovating it all. Well, we’re not doing anything — we’re hiring our Polish friend who’s done so much already in our home.

This last unknown is finally known: when will we ever get that bathroom done…

How Much Time?

Sometimes, I find myself wondering just how much time I need to give students to finish an assignment. If they’re playing around and wasting time, then they’re doing just that — wasting time. Why should they get extra time? But if I assess what they do turn in, then it’s so incomplete that it’s more an assessment of behavior rather than skill.

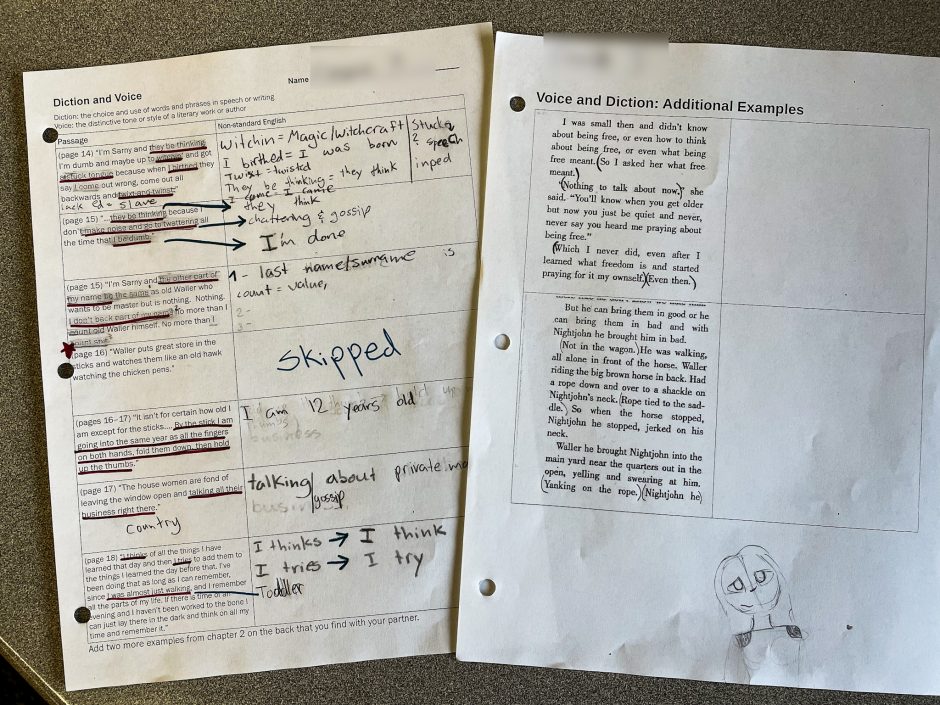

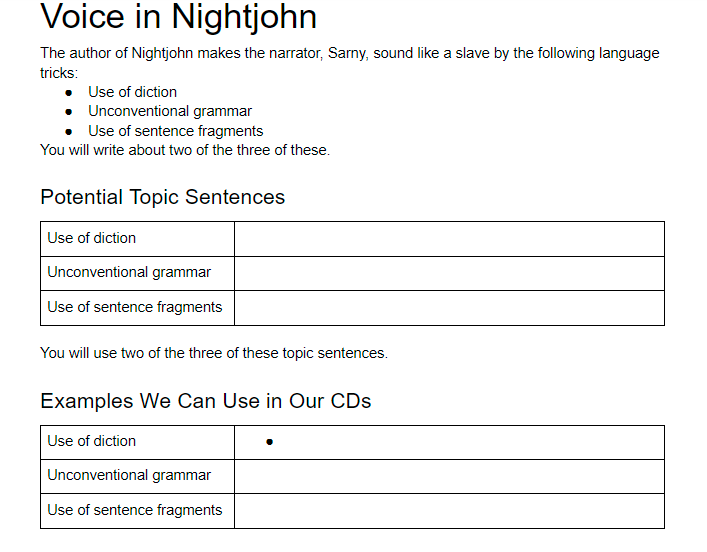

Take our current project: we’re writing about how the narrator effectively creates the voice of an uneducated slave girl in Nightjohn by judicious decisions in diction, regularly irregular grammar, and extensive use of fragments. We’ve gone over all this stuff. We’ve practiced finding it. We’ve found it. We’ve noted it.

I’ve planned out everything so that what they have to do is less figuring-out-how-to-do-it and just doing it. We determined potential topic sentences as a class. We found evidence in groups. (Much of the evidence they already had — it should have taken them about 5 minutes to find evidence because it was in earlier work.)

At this point, students who have been focused and working well are almost done; those who haven’t are not close to done. They should work on it over the long weekend. Will they? Of course not. How do I know this? Fifteen years of teaching eighth grade at this school has shown me that 85% of the kids in on-level classes just won’t do anything on their own at home. Anything at all.

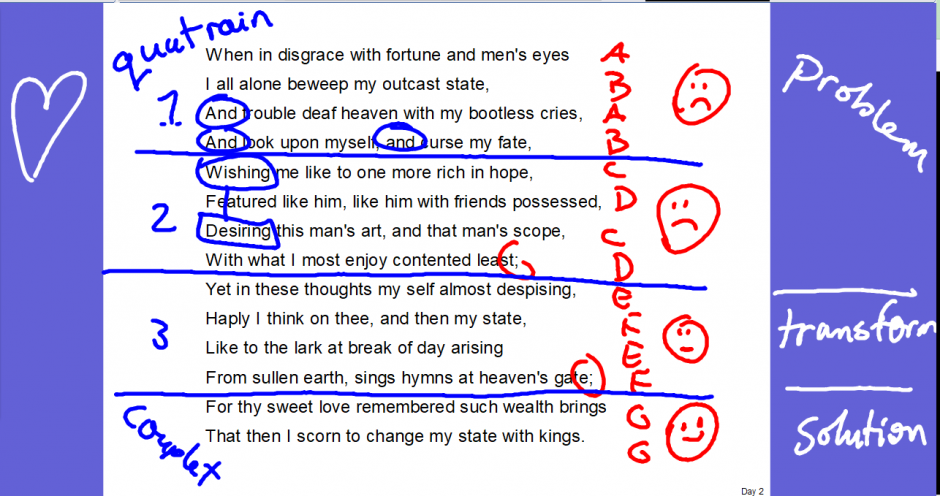

English I students, on the other hand, finished up their analysis of “Sonnet 29” with an examination of the elements of a sonnet:

We then turned our attention to “Sonnet 18” — undoubtedly Shakespeare’s most famous sonnet:

Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?

Thou art more lovely and more temperate:

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,

And summer’s lease hath all too short a date:

Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines,

And often is his gold complexion dimm’d;

And every fair from fair sometime declines,

By chance or nature’s changing course untrimm’d;

But thy eternal summer shall not fade

Nor lose possession of that fair thou owest;

Nor shall Death brag thou wander’st in his shade,

When in eternal lines to time thou growest:

So long as men can breathe or eyes can see,

So long lives this and this gives life to thee.

The difference in what they’re working on is striking, but it’s less striking when you see the difference in how they work. The kids in the honors classes, by and large, are focused and studious. They do homework when I require it. They pay attention when I’m demonstrating. They stay on task when I ask them to cooperate on a task. They remain silent when I tell them I want them to do some step or other on their own.

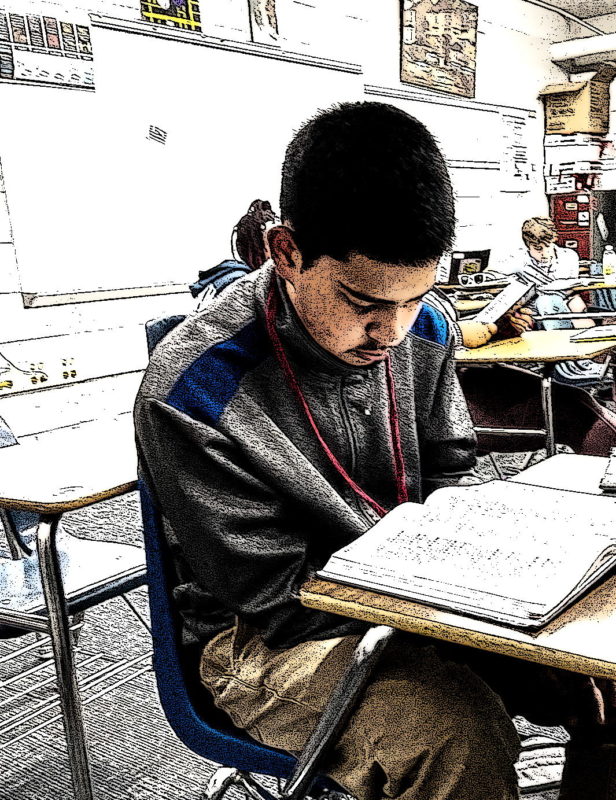

Reading

I knew taking the picture might break the spell: an at-risk student who, of her own accord without any prompting or suggestion, chose to read a book during free time after lunch might not be thrilled about having her picture taken. But on the other hand, it’s a picture of success, and when it’s a kid you’ve already grown to love in a way, a kid you’re already pulling your hair out over and cheering on and fussing at with a smile — you go ahead and take that chance.

Sure enough — “Mr. S! Don’t!” And the spell was broken. But unlike many magical moments, this one has evidence to back it.

Football Glory and Critical Thinking

When we lived in Asheville, I worked for one year at a day treatment facility for kids who’d been expelled from alternative school. It was a tough bunch of mainly fourteen- and fifteen-year-olds. At one point, though, two boys who’d known each other “on the outside” (as they’d referred to it) were in the program at the same time. At lunch they’d revel in their former football glory, recalling magnificent plays they’d been a part of and sharing in the sorrow of those losses that had stung so badly. At one point, one of the boys mentioned having a recording of one of those games.

“Really!?” The program director was incredulous, but he managed to talk the boy into bringing in the video.

A couple of days later, during afternoon free time, the kid put the video cassette into the VHS player and pressed play. Soon, the director was howling in laughter as he watched a little league game in full chaotic, cute glory.

“Man, I thought you were talking about games you’d played in middle school or something,” he laughed. “I didn’t realize you were talking about second grade!” He was just good-naturedly ribbing the kids, and they took it fairly well.

Looking back on it this evening as I jogged laps in a parking lot while the Boy had soccer practice, it suddenly took on a newly instructive dimension for me. Had any of us really thought about it, we would have known it could not have been middle school football the boys were talking about. They’d experienced little success in middle school, showing out enough to be removed from the setting altogether. Even the most gifted player is going to have to meet certain standards — administrators might bend some requirements for such a boy, but there are at least some requirements. These boys couldn’t even make it through alternative school let alone the less structured setting of a typical middle school classroom, so there was no way we adults should have assumed they were talking about playing organized football in the last several years.

We made those assumptions, though, because they neatly and immediately fit our assumptions. When a fourteen-year-old boy is reveling in past glory, we don’t expect it to be from early elementary school but from the recent past. It’s an immediate and logical assumption that we make without even being aware that we’ve made such an assumption. The thing is, we make these kinds of assumptions constantly throughout the day. We couldn’t function, I’d argue, if we were to give extended critical thought to each and every decision we make and every thought that flits through our mind. The trick is being aware enough of our thoughts to have as a conscious option the ability to switch on our critical thinking and go, “Now, hold on there.”

It’s one of the reasons I enjoy teaching literature to middle schoolers. It’s just those “Now, hold on there” moments that critical reading encourages.

A Way Out

You shouldn’t use a student’s behavior as a good example of bad behavior, but I did just that today. We’d finished early, and I was talking to the kids about three questions we should all ask ourselves before speaking:

- Does it need to be said?

- Does it need to be said by me?

- Does it need to be said by me now?

The motivation for this gem of advice was from a young lady who speaks her mind — literally. If it comes into her head, it soon comes out of her mouth.

It can be disruptive, to say the least.

As I was talking about the first question, another student made an unrelated comment to our talker.

“See?” I said to the girl J and class, “that was a time when the answer to the question ‘Does it need to be said?’ was probably ‘No.'” I said that and thought, “Perhaps I shouldn’t have said that.”

And on cue, the girl starts up with the disrespectful arguing: “I was talkin’ quietly. I wasn’t botherin’ you or interrupting anything.”

“Perhaps, but you certainly are now,” I smiled. I glanced over at one of the most studious kids in the class, a girl I already think I’ll remember for the rest of my teaching career, such is the positive impression she’s made with her work ethic and charming personality. She was aghast.

“Make the tension go away!” her face begged.

So I attempted to do that: “It’s okay,” I laughed to the class. “J and I had this all planned as a good bad example.” And I thought, “Please, girl, for the love of all that’s possessing common sense, realize the out I’ve given you, fake a smile, and say, ‘That’s right, Mr. S.’ We’ll drop it. You’ll save face. I will have deflected a challenge to my authority. Everyone else will take a breath and think, ‘God, I’m glad that’s over.’ We’ll all win.”

“No, we didn’t!” she blurted out loudly.

It was really difficult restraining that laughter bubbling up inside me…