I grew up in a cult, and that means I grew up learning how to be adept at double-speak and managing cognitive dissonance in many areas but especially in questions of power. We were taught that God was unquestionably in charge and not to be questions — nothing extraordinarily unusual about that since that’s a fairly orthodox position. However, we learned that we had to transfer that kind of blind obedience to God’s only true representative on Earth, Herbert Armstrong. Not only were we to obey him but we were also to assist him. Our job was not to proselytize or to try to win converts to our religion. That was God’s job through Armstrong’s preaching. Our job was simply to support him, and there was only one kind of support he wanted: fiscal. We weren’t to question what he did with the money we sent him. We weren’t to entertain doubts about the wisdom of his decisions even when they seemed to be causing problems members individually or the church as a whole.

The most wide-spread cult in America today is unquestionably MAGA with its unquestioning loyalty to Trump. Every now and then, I read something that seems so perfectly parallel to how members of Armstrong’s cult used to talk that I feel I’m simply hearing a sermon from my youth.

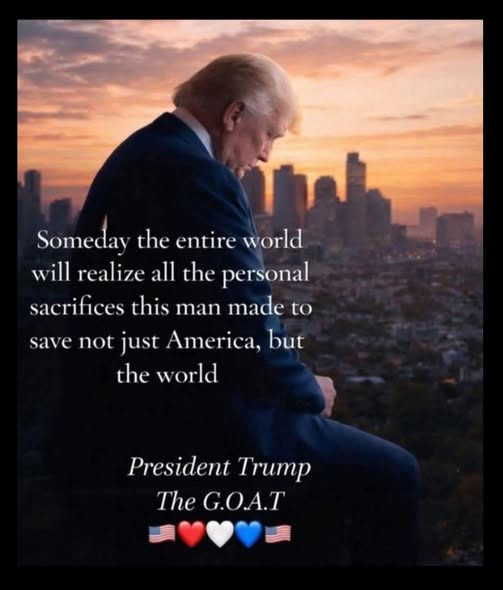

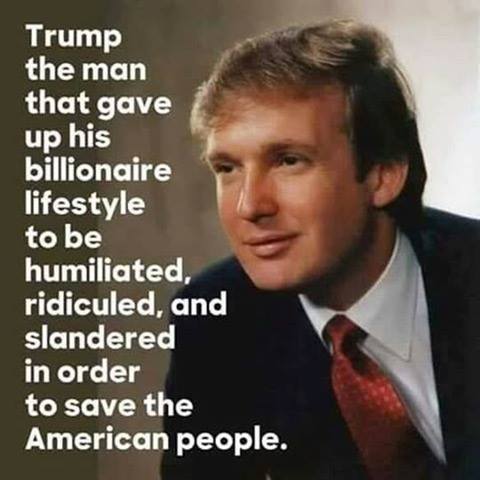

I discovered this picture posted on social media recently, and combined with the poster’s own thoughts, it fairly accurately mirrors all the destructive thinking patterns of Armstrong’s own cult.

The most immediately obvious parallel of the hagiographic nature of followers’ descriptions. This idea of Trump sacrificing so much to save America has been around in memes for a while.

This is one my own mother shared early in Trump’s first term. It has much more blatantly messianic tones than this newer one, but the sentiment is the same.

The original post included the author’s own thoughts about Trump’s recent actions:

Yes! He is TRYING to save our whole world!! Trying to demand peace. The road to that is very rocky, but you have to be willing to do it and endure any roadblocks and hiccups along the way. But if you stay strong and stay faithful, you are doing your part.

Almost every sentence of this echoes the thinking that pervaded my cultic upbringing.

“He is TRYING to save our whole world!” This notion parallels notions that Herbert Armstrong and his organization were literally the only thing holding at bay the complete destruction of not just America but the whole world.

Additionally, Trump is “[t]rying to demand peace.” This is in direct opposition to what we’re seeing with our own eyes. This gaslighting is critical to cults. It allows followers to ignore their own experience and thoughts when they contradict the official story. He’s not killing civilians in American cities, extra-judiciously attacking boats in the Gulf of Mexico, or initiating a completely unprovoked war. That’s violence. That’s not what he’s about. He’s about peace. He’s said it himself countless times over the last ten years, and just because it seems to contradict his actions, we just have to listen to him and understand that he is trying to create peace through his violence. Doublethink at its best.

However, we must understand that the “road to that [peace] is very rocky, but you have to be willing to do it and endure any roadblocks and hiccups along the way.” Again, don’t pay attention to your own eyes. Ignore the reality you’re seeing. These are just hiccups, roadblocks to our complete supremacy and world peace. Just remember that “if you stay strong and stay faithful, you are doing your part.” Your part is not to think. Not to question. It’s to support — without question, without thought, without doubt. Our dear leader knows best. After all, look at all he sacrificed to reach this moment. Ignore the riches he’s created for himself by using his position. He sacrificed because he said he sacrificed.

I intentionally retained the pronoun-antecedent ambiguity of the above paragraphs simply to illustrate the fact that one could use either “Trump” or “Armstrong” as the antecedent, and the result would be identical.