What do you do when it’s raining, raining, raining? When we took our trip to Charleston a few months ago, we went to watch the Dylan biopic that first day because of the weather, but there’s no movie theater in Jablonka. Where could you possibly go when you’re in a small village relatively far from any town?

Well, when there’s a break in the rain, you can take the dogs out for a walk. There’s always something to look at and to talk about with the Boy. So that’s exactly what we did this morning. The little suka that Babcia adopted some years ago (a poor pup clearly abused earlier in your life–she’s terrified of me and all men in general) got out of her collar and caused the Boy no bit of initial worry.

“She’ll follow us and make it back home,” I assured him.

We cut through the jarmark, which, by that time, was closing up.

“Almost nobody is there,” the Boy informed me when I finally dragged myself out of bed at nearly nine this morning, exhausted from waking to take K to the airport and then unable to fall back asleep at 4:30 when I got back to Wujek D’s house yesterday.

(K made it home safely: the animals are thrilled to have part of the family back home, but still wondering where in the world the rest of the family is.)

Finally, after lunch, we decided the best place to go was the outdoor train museum we seem to visit every visit lately. It was a little different this time: the Boy wasn’t as fascinated with every little thing like he was during our first visit, and the cold rain was a radical difference from the unbelievable heat we endured in 2022.

We talked about the fact that all this equipment was once new, modern, and cutting-edge. We entered an empty passenger wagon that had nothing but a wooden floor and rusted ceiling:

“Just think, son–at one point, someone climbed into this carriage and thought, ‘Wow! A new, modern car!’ And now, it’s difficult for us to imagine traveling like that, difficult to imagine the carriage as anything but an exhausted antique in a museum.”

The changes in Warsaw between the time I first explored the city in 1996 and finally returned with my family in 2017 were enormous: it was almost an entirely new, entirely different city. I’m sure the changes in the intervening eight years have not been as drastic, but certainly it has grown: new skyscrapers, old buildings torn down or renovated, more diversity in its populations–all the changes I observed in 2017 continued to some unknown end.

Krakow, on the other hand, is a city that seems to have changed little in those years. The Old Town has a lot more variety in its culinary offerings; the prices for apartments in that part of town are likely out of reach for the vast majority of Cracovians; there’s much more diversity in the population of the city and in the tourists who visit it; some buildings have been renovated a few new structures have appeared. Still, it is by and large the same city I visited first in the summer of 1996.

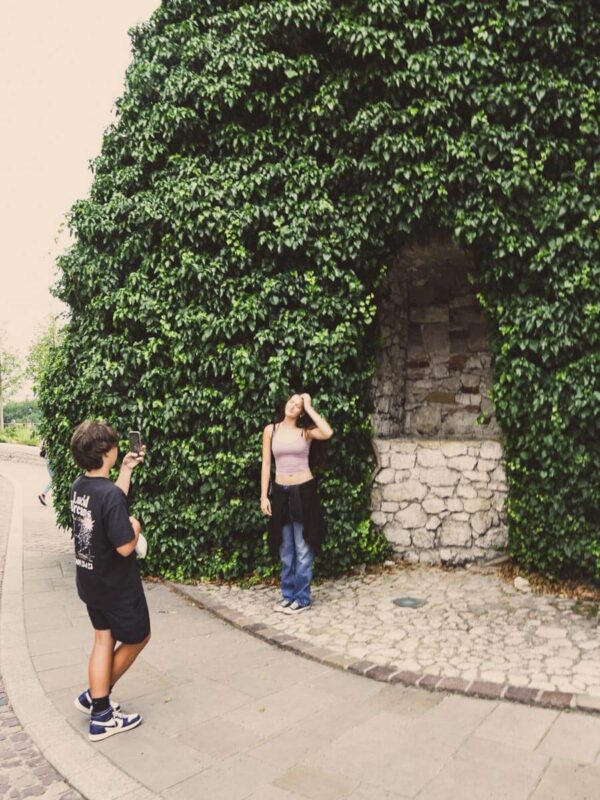

The kids and I explored a bit of Krakow today since we were already so close having taken K to the airport for her return to the States. (The kids and I will be staying another two weeks.) L’s knee is still giving her problems (it all started last week in the mountains), and the forecast predicted severe thunderstorms and continuing rain starting around two, so we made a short day of it. We really only went to two major tourist attractions: the sukiennice on the main rynek for the Girl to get a few more gifts for friends, and Wawel because, well, it’s Wawel.

Along the way, we of course stopped in several shops that lured the Girl’s attention with vintage dresses or exotic plants, and we took a break in a charming little cafe just off the rynek for coffee (three lattes, please). All told, we spent there only about four hours–certainly not enough to do the city justice at all, but we’ve all been there so many times that it felt fine just reliving a few highlights. Besides, relief for an aching knee is more important than any tourist attraction.

We hiked 26 kilometers with 938 meters of climbing. It was, in short, an exhausting day.

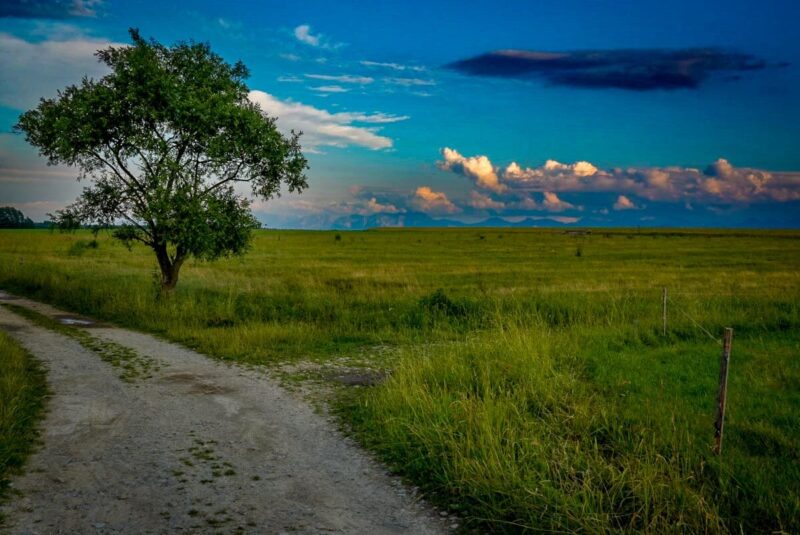

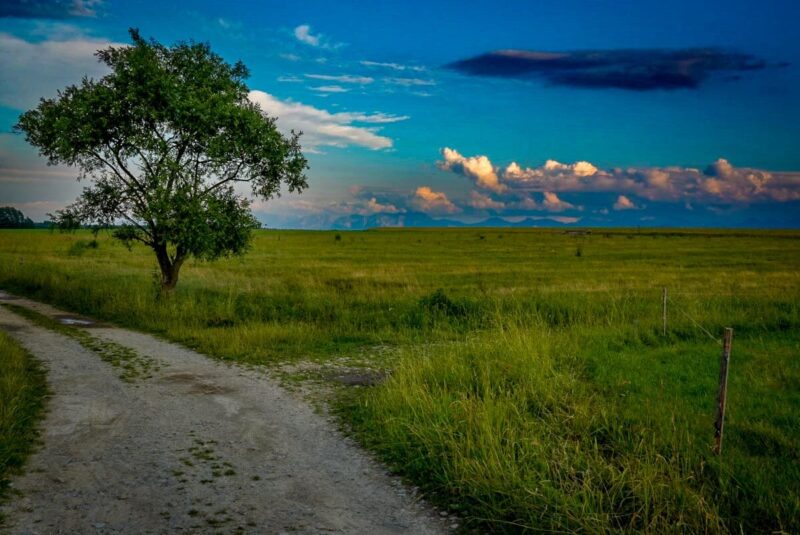

It’s a walk I’ve taken countless times. The first time I took this walk was with Kinga probably 28 or 29 years ago. At that point the deliniation between houses and fields was clear. Most all of the houses were at 15 to 20 years old, and those that were new were likely incomplete. The block walls and slab floors were done. It had a roof, and there were windows. Often there were even window boxes filled with flowers. Yet the exterior of the house was still, as the Poles would call it, raw–surowy.

Once in the fields, one saw several things consistently. Fields planted with various crops often potatoes or grass for livestock streched out in various directions, sometimes to the horizon. An farmer might be making loops in the field as he cut that grass or turned the grass as they processed it into hay. Strang pyramids of may might line another field–triangular wooden frames piled with grass it for the final drying process. Families might be loading the grass from the frames to horse-drawn wagons to be taken to the barn storage for winter feed. But most of all there would be cows. Cows everywhere.

Now, almost all of that is gone. The fields have been turned under and houses constructed upon them. The cows have completely disappeared except for exotic bulls that are likely more status symbol than anything else. The A-frame with hay drying on them (drabiny the Poles called them—ladders) are also a thing of the past. In short, the Polish village to which I arrived in 1996 has completely disappeared. Cows are no longer a basic necessity. They’re simply an expense. Giant hay balers have replaced the drabiny. And the people in the new houses are once the children of those farmers whose crops and dairty once supported them. But dairy production is now on an industrial scale; crops are grown on an industrial scale. The small family farms are no longer profitable, so they disappear.

Now, I take a walk in the fields and there are no people. There are no cows. The only sound of humanity that I hear on the cars is passing on the road and the distance.

As we were driving back from Nowy Targ yesterday after getting ice cream, I was talking to my brother-in-law about how I regret not taking pictures of the communist, social realist style of architecture that was so prevalent when I first arrived in Poland. There was the bus stop in Nowy Targ, which was a textbook example of 60s Eastern European architecture, where I sat for many hours waiting for a bus here or there. I have almost no pictures on the inside and absolutely none of the front of the building. I think about the old bus station in Kraków, where I also waited for countless hours.I also have no pictures of it. Most significantly, the apartment in which I lived for three years, which was pulled down during our last visit in 2022, survives only in my memory. I have not a single shot just of the interior of that building or my apartment. I have only some pictures of the apartment when I went for a visit in 2001. I poppoed into the apartment after the American who replaced me had moved out and cleaning ladies were battling the complete mess he’d left behind. I took a picture more of the wreck than of the apartment. Those were the elements of my everyday life I should’ve realized would change, or even disappear, and I never took a single photograph.

It occurred to me during the walk today, though, that all the pictures I’ve been taking while on walks in the fields over the last 30 years have been just that: images of a disappearing world. Unlike the brutalist architecture of Eastern Europe, which I knew would eventually disappear or be renovated beyond recognition, it never really occurred to me that the village too would disappear. But it should have: that’s exactly what happened in America. That’s exactly what has happened in various countries in western Europe. It hasn’t disappeared, but it has transformed beyond recognition.

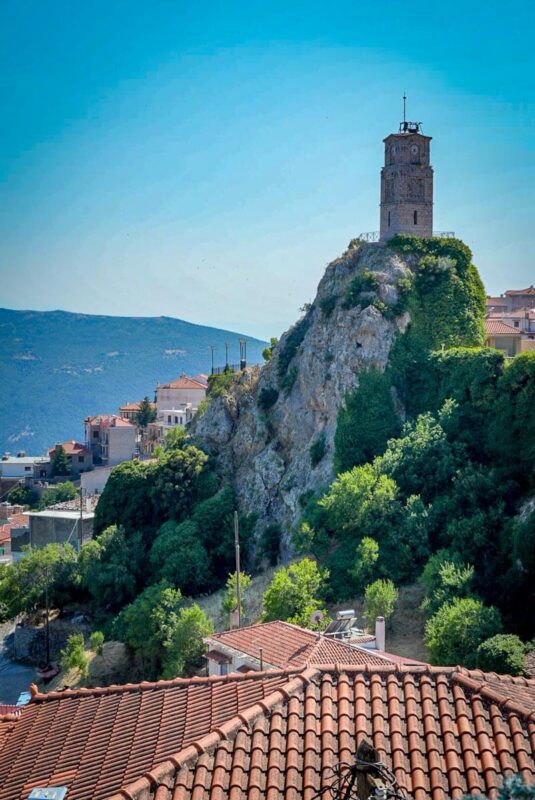

It occurs to me, though, that this has really been the theme of our visit our European adventure. We spent five days in Greece visiting ruins of civilizations that never really anticipated their own demise. They hadn’t foreseen the technological advancement of the coming millennia that would make every single element of their daily life completely redundant, unnecessary, or even silly.

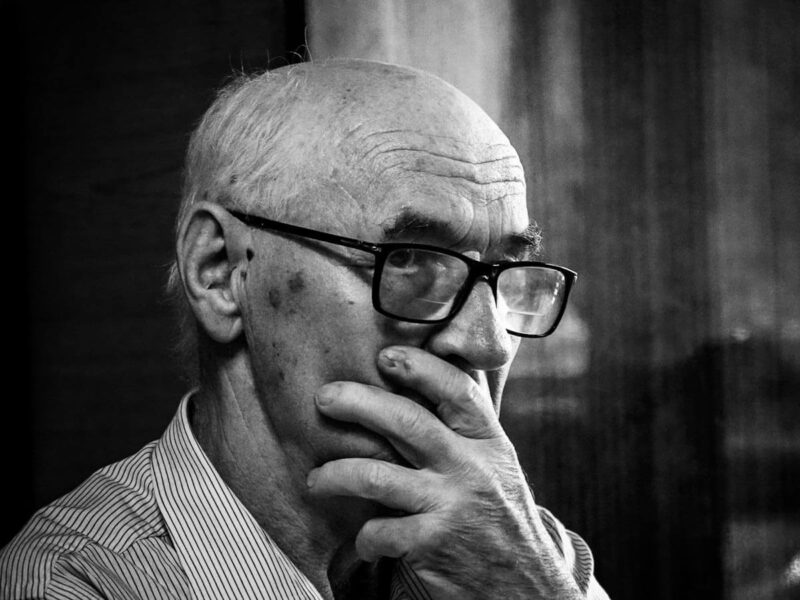

We as a family are also entering a time of great change, a time of endings. L will soon be heading out to college, and since we are going to be trying to establish Florida residency for her to decrease costs during her second year at Florida, she won’t be coming to visit nearly as often as we would probably like. E has one more year of middle school, and then, as with L, high school will disappear in a flash and he too, will be heading off to college. For all we know, this might be one of the last if not the last time we are here together as a family of four. It’s depressing to think that way, and I don’t think it is the last time we are here as a family of four, but it certainly won’t be a certainty anymore.

Such endings used to be heavy for me. I’m such a sentimental sap that when an ending appears, I want to wallow in the potential nostalgia of that moment. Yet the older I get, the easier those ends come. A school year ends, and instead of thinking despondently, “Oh, I will never see these kids again,” I simply think, “Well, it’ll be a new group next year.” Perhaps that is not the best example: school years by their cyclical nature never really end. One year simply replaces the other. One group simply replaces the other. No one will replace L when she goes off to college. Nothing has replaced these cows in the field now that they’ve gone. Some endings are just that: endings.

For a first day in Poland, it couldn’t get much better than today: a day that slipped by without a pause as one moment bled into another to form a day that’s a blur and so much more.

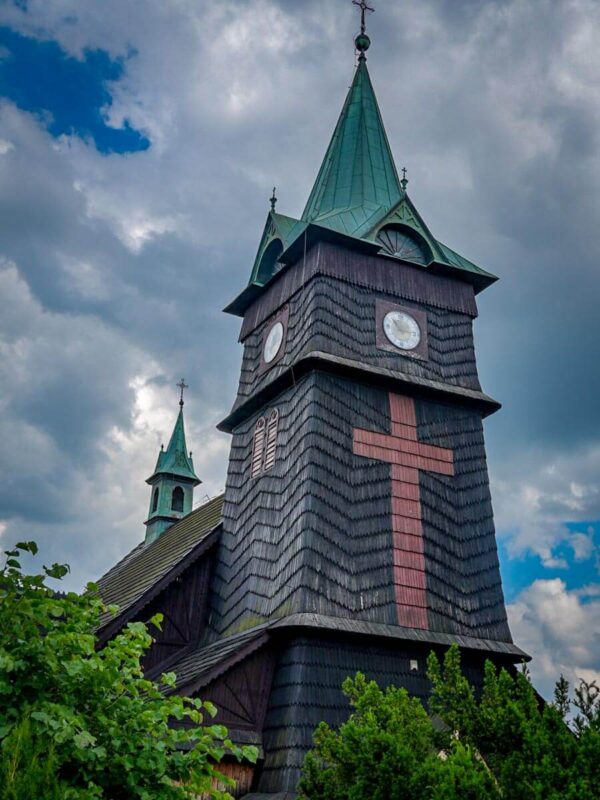

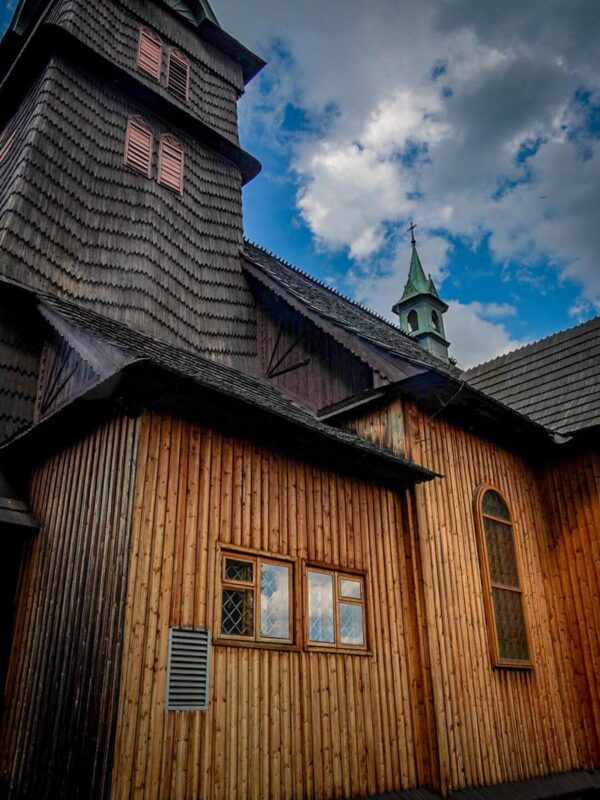

“Tomorrow, we’re going to church at eleven!” Babcia announced, telling D that he was to drive from their home outside Krakow (where we were last evening) with all three kids and meet us in the church. “I haven’t had a chance to show off my whole family in the church in a long time!” she declared. In fact, I suppose she hasn’t had a chance to show off her entire family at all: the last time I remember us all being in the church here in Jablonka together was when L got baptized in 2008. That’s when we took this picture:

Naturally, when we got back from church, we had to recreate that photo:

Only one of them could fit in the swing, and poor S, who is the middle in age (one year older than L and a year or two younger than W), has been left behind in the height category.

After we had a light lunch, we decided to head to Nowy Targ for ice cream. Sure, there’s ice cream in Jablonka, but it’s not the same as Lodziarnia Żarneccy.

“Isn’t this just the best ice cream in the world!” K was raving as she savored her cone.

“Maybe for your generation, Ciociu,” S politely demurred.

Your generation? That makes sit sound like some kind of disease, doesn’t it? Be careful, Cousin S: middle age is very contagious, and it has a way of sneaking up on you unawares.

Once we got back, it was time to prepare for the day’s main event: Babcia’s seventy-ninth birthday. We’d invited all the aunties and cousins who live nearby, and we had a classic Polish ognisko with grilled chicken, kielbasa, boczek, kiszki, bread toasted over the fire, some beer, some wine, and a lot of talking and laughing.

It’s a minor miracle that any flight at all leaves Athens airport on time. We saw the chaos when we landed and quickly decided we might feel safer with more time than less when it came time to head to Polska. We arrived at 10:45 for a 2:00 flight. Admittedly I thought that was a bit excessive, but I knew K would feel more comfortable, and she was probably right, I reasoned.

We unloaded our baggage from the taxi and entered terminal one at check-in desk 60. Not knowing where to check-in, K and the Boy waited with our baggage as L headed one way and I the other looking for the LOT desks. I made it to desk 1 without seeing anything, so I asked an airport attendant I passed. He liked it up: we were to check-in at desks 168-171—literally in the last desks in the terminal. “They will open the desks two hours before the flight,” he explained. I glanced at my watch: we had an hour to wait.

We began weaving our way through the crowd of passengers waiting to check in, heading to or from their check-in desks, and just sitting or standing with their luggage. It must be that chaotic regularly because there was a passage of large round decals forming a path on the floor directing people to find somewhere else to sit or stand as the decals indicated a walkway.

We quickly figured out why.

We made our way to desks 168-171 and found a spot to camp out, but within twenty minutes we realized we should go ahead and get in the line though no one was even at the check-in desks yet. Poles are expert queuers and there was already a line. (When I lived in Poland, I’d arrive at the administrative office in Krakow where I renewed my visa well before it opened only to find the line stretching halfway around the block.) Gathering our luggage, we joined the line, and to our surprise, four attendants soon began checking passengers in as the line grew behind us. With only about ten to twelve groups of passengers in front of us, I was sure wevavimg already checked in online, would be through quickly.

The first clue that the whole process might be a bit more time consuming than we anticipated was that the fourth attendant was not checking anyone in. Instead she was consulting with the third attendant, helping her almost continuously, and when she wasn’t, she was talking to someone on the phone. After a few minutes, the second attendant left while she was helping someone. He stood there for a while until the first attendant finished with her passenger and then finished with him. There was some problem or other with his baggage, and he must have been there ten to fifteen minutes. Meanwhile, the only other attendant working must have been completely inexperienced for she kept asking for help from the assistant in the fourth desk who was moving between five activities: talking on the phone at her desk, talking to the attendant in the third desk, taking on the phone at the third desk, talking to the worker at the first desk, and taking on the phone at the first desk. After a while, a fourth attendant came but she also checked no one in and insisted was apparently supervising the whole incompetent mess. Each group of travelers was taking at least eight to ten minutes to check in, with one group of Canadian travelers working on the process for well over fifteen minutes. In short, though we were very close to the start of the line, it took us well over an hour to get checked in.

Was it a technical issue, incompetence, inexperience, or some mysterious combination of the three? I feel we got an answer when we were checking our luggage.

After printing and attaching our first luggage label, the attendant told us, “I don’t see that you’ve paid for any checked baggage,” pointing to the screen (which we couldn’t see of course). K pulled up the reservation on her phone and showed her. She nodded in assent, ripped off the label, printed a new one and attached it. “Incompetence and technical stupidity it is,” I thought as we walked away.

Looking at the line snaking down the terminal, I wondered if there was any hope at all that we could take off on time. There were three times more passengers behind us than in front of us. “If this pace keeps up, it will take three more hours just to check everyone else in,” I grumbled. I’m really skilled with complaining when the perceived problem seems to be due to others’ incompetence, and I have an absolute gift at reading incompetence into my inconvenience.

Suffice it to say, we all somehow made it through and we took off only twenty minutes late.

We made it to the required attractions here in Athens; we visited an island; we drove up to Delphi and experienced the charm of Arachova. It’s been go! Go! Go! We’re tired, and today was a day to relax. Do we go to a beach? Do we head to an island for more discovery? In the end, on L’s urging (she’s picked most of our adventures, and she’s chosen excellently), we went to Lake Vouliagmeni just south of Athens. We considered renting a car, but who wants to drive in Athens again?

“It would take an hour and a half by public transport,” we told the kids, not sure whether or not it would discourage them. It did not. “That’s fine.” So our journey today was a typical city journey: we walked a few blocks to our Victoria (Βικτώρια) metro station where we took the metro a few stations to catch the 122 bus down to Vouliagmenil. We weren’t the only ones with that idea, though, and soon the bus was positively packed as we crawled through southern-Athens traffic.

“This gives you an idea of what it was like for me to be a student in Krakow,” K explained to the kids

Once at the lake, we discovered what the Garra Rufa fish do: they’re also known as doctor fish or nibble fish, and they do just that. Within moments of entering the water, I looked down to see they’d completely covered my legs. Once I eased into the water completely and relaxed, they swarmed my arms, my chest, my back. It was strangely addictive.

We ended up staying there for hours: none of us really wanted to leave.

When L began picking out places she wanted to go (this Athens portion of our trip is, after all, her graduation trip), the ruins at Delphi were very high on the list. At first, I was opposed: it’s at least two hours out of Athens, and I wasn’t fond of the idea of driving in Athens. I had no firm reason why; it just didn’t sound pleasant. It was just a feeling I had. After all, “chaos” is as Greek a word one could ever imagine. Still, she kept talking about it, and I relented. (Truthfully, it really didn’t take that much: I’m a reasonably confident driver, and while I’d never drive in many countries–India comes to mind–I knew it wouldn’t be all that bad.)

We headed out today after breakfast. While K and the kids were in a pharmacy getting something for the itchy bites plaguing L (and strangely enough, no one else), I went to the car rental place just a block away and started filling out the paperwork. As we headed out to the car, the representative asked casually, “You can drive a manual, can’t you?” Of course, I can drive a manual, and yesterday on Aegina I drove a manual. But there’s a big difference in driving a manual on a small, sleepy village where the biggest challenge was ridiculously narrow streets. Narrow streets pose no challenge for a manual transmission. Hilly terrain with lots of stop lights does indeed pose a challenge. It’s not a big deal once you’ve gotten the hang of the clutch in your car (just how loosy-goosy is it?), but to acclimate yourself to that clutch in a busy city where stop lights hide on poles on the corner of streets — that did not sound enticing.

We made it through Athens and to the quieter roads of the countryside, but it was indeed a stressful driving experience. Scooter drivers and motorcyclists split lanes constantly, which is technically illegal, I read, but one would never know it watching their behavior. There were portions of the road where there were no clear lane markings, and where I drove it appeared to be a three-lane road whereas just in front of me, it seemed like a two-lane road. Once we made it to the quieter streets, it was a bit better, but double middle lines apparently mean nothing to Greek drivers, and the people being passed casually pull onto the shoulder to get out of the way.

Though I was initially less than thrilled about driving two hours (with morning traffic, it was more like three hours) to get somewhere while on vacation, I came to appreciate the opportunity it offered: we were able to see parts of Greece that we would never have seen otherwise. We passed through small villages and quaint towns. We saw how ordinary Greeks live, even if only a glimpse. It also gave us freedom: when we found a town — Arachova — we thought charming, we were able to work that into our return plans as a dinner stop and a place to get out for a lovely walk.

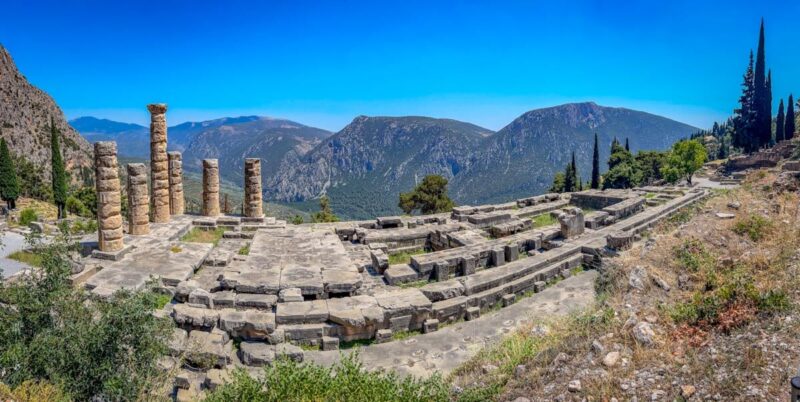

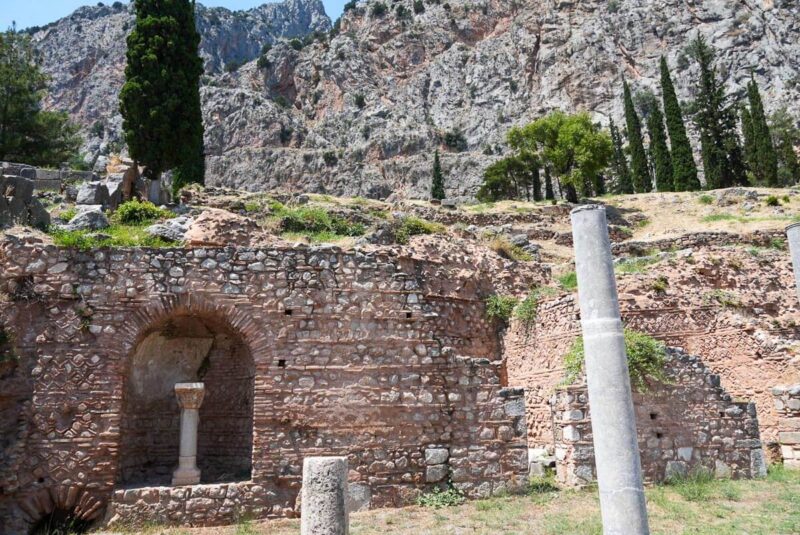

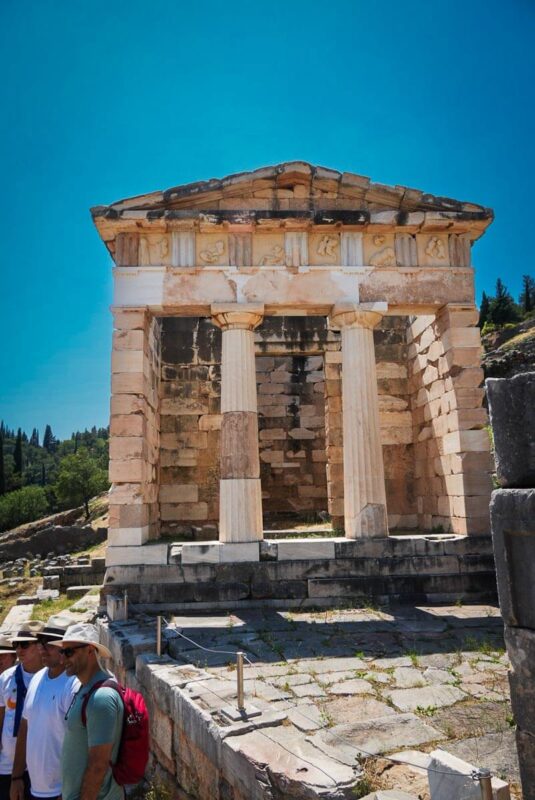

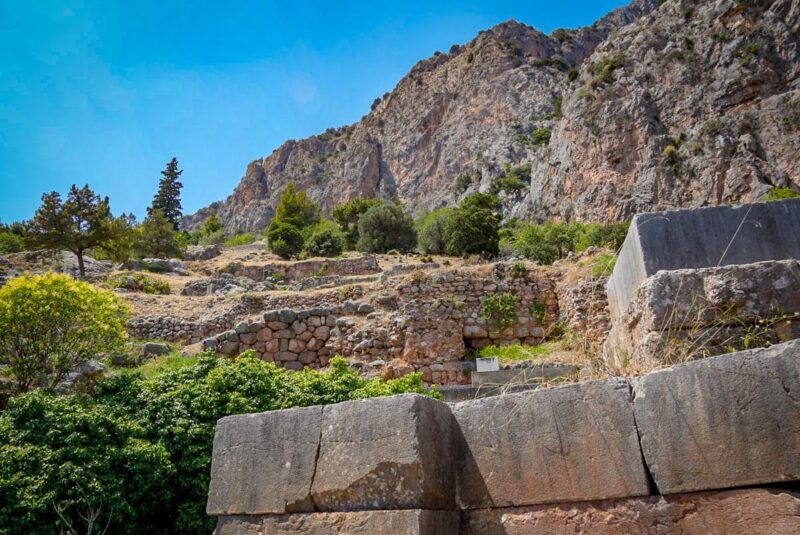

Delphi itself was, as so many things here are, overwhelming. The thought of how much work it took to create something like that in a time when there were only the simplest of machines is almost overwhelming. How could they do something like that? And then the silliness of why they did it: the Delphic Oracle needed a special place to commune with Apollo and tell his priests his will using what I inferred was glossolalia. In other words, she spoke gibberish and the priests “interpreted” it. That sounds a lot like modern Evangelicalism, which is depressing: it means we as a species have outgrown this silliness in almost 2,500 years.

On the way back we stopped in Arachova for dinner. It was a stunning little town. “We should learn Greek and retire here,” K suggested.