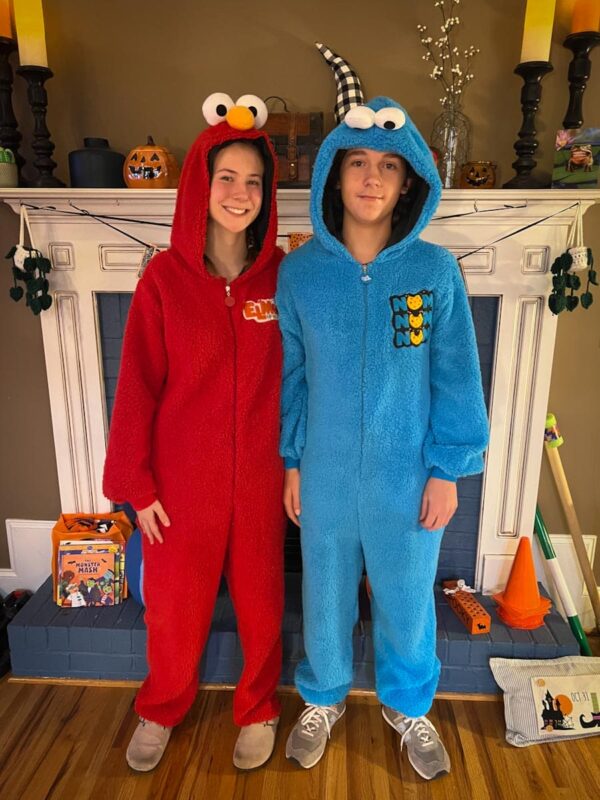

Costumes

At Furman

Fall Soccer

Halloween 2025

Final Spooky Concert

Social Media Wonderings and Wanderings

Questions

One of the most challenging things about being a parent of a teenager is that constant uncertainty that you’re getting the whole story. It’s not that you think they are lying to you. It’s not to say that it’s even a conscious effort to withhold information: they likely don’t even know themselves whether they’re telling the whole story. Being awash in hormones and emotions that are all new to them, young teens have only started trying to figure out who they really are, who they ultimately want to become, what they want to be, what they want to achieve. You’re never quite sure if everything is all right of the mannerisms, the silence, you suspect it’s not. And when they say, “No, I’m fine. I’m just tired,” you wonder if they’re fooling you, fooling yourselves, or fooling everyone.

“Are you all right?” That’s probably the most spoken word in the household with one or teens.

We try to replay our own teen years in our head in such situations, and realize that sometimes we wouldn’t want to talk. It was just that. Nothing was wrong. It was no depression or anger. We just didn’t feel like talking. But it’s so different when you’re on the other side. There must be a reason you don’t want to talk. There must be a reason for everything, because that is what parenting feels like sometimes: looking for reasons.

“I’m just tired,” comes the response. That was an excuse we used, t0o.

The thing is, we have no more answers now as adults that we did kids, and while all adolescent identity are instructed in a swirl of questions, it still feels like we as parents have more questions. Certainly more questions and answers.

It all just illustrates my childhood was usually the easiest part of any one’s life in the modern era. What questions has children were simple, when we trusted the adults in our lives about the answers they gave. Even later in life what do we realize that not all those answers were correct or healthy, we usually remain in blissful ignorance of all these doubts as children.

First Concert

Soccer Saturday

The Boy’s team has had quite the season this year: up to today’s game, they had allowed only a single goal. They beat most of their opponents handily. Today was different. They were up 3-0 by the first half, so the coach put in a new goalie. Someone who’d never played goalie before. I suppose the reasoning was that if the other team started scoring, he could make adjustments and put back one of the two boys who usually play in the goal. That seemed unnecessary, though: the boys added three more to the score, invoking the mercy rule, which means they were no longer allowed to score. In the final minutes, though, the goalie made a mistake that left too much room and allowed a shot into a virtually open goal. The boys still won 6-1, but E was a little disappointed: “I wanted to finish the season with only one goal scored against us.”

Houses on the Way

Are They Listening? (No, They Are Not)

Today’s journal prompt for students touches on a universal motif:

Have your parents ever said something like, “Listen to me!” or “You’re not listening to me!” when they’re talking to you? What are you doing when they say that? Why do they think you’re not listening? What does it mean to listen?

We’re working our way through a unit on communication, and this week, we’ll be focusing on active listening. It should be a fairly straight-forward week, especially since we only have three days in school: Monday and Tuesday constituted our fall break, one week after and 100% longer than the Boy’s. (Wasn’t fall break three days at one point? At least two days. Greenville County Schools cut it back this year or last, I suppose.)

As students work, I find myself thinking now-familiar thoughts: this work is so much easier than teaching English, and it’s also easier, I think, than the other teachers’ responsibilities, which leaves me feeling a little guilty.

Why should I? It’s not like I’m spinning my wheels with the kids, just giving them busy work and straight 100s, which I theoretically could. I think that might be one of the reasons why the principal, who was my grade-level administrator at my old school, hired me to teach this leadership class: cruising is so tempting, and she knew I wouldn’t do that.

Compared to what I was doing, I certainly feel like I’m cruising. Gone are the hours of reading and providing feedback on a seemingly-endless pile of essays. Gone are the hours of tedious planning. Gone are the painful and endless meetings about “data.” (I swore last year I wouldn’t use that word anymore. Now that the year is over, perhaps I can lighten up.) Gone are the emails asking me to provide clarification for this or that element of a lesson that the instructional coach (what in the world even is that job? do some research: though every school has one, you won’t find a consistent definition or list of responsibilities) had observed and made notes about. Gone are the meetings leading up to a given benchmark during which administrators (and the instructional coach) encouraged us to encourage our students, motivate our students, push our students to take the benchmarks seriously even though almost none of the teachers took them seriously because of the lack of transparency in the benchmark and our inability to use it as a teaching aid in any sense because of its proprietary nature.

Count that: thirteen individuals with a job title that includes “Superintendent” in it, with the attendant six-figure salaries. With only an average of $150,000 a year — and the superintendent himself making over $300,000 — that comes to $1,950,000 for the salaries of thirteen people who work in public education and do little to nothing directly with students. They do nothing with the teachers. They are so far removed from actual education that to call them educators in anything more than a theoretical sense is insulting.

I often felt the district administrators, from the Superintendent to the Deputy Superintendent down through the seven (yes, seven) Assistant Superintendents for School Leadership, the Assistant Superintendent for Transformation, the Associate Superintendent for Academics, and the Associate Superintendent for Operations all could have used a lesson or two in active listening.

When my previous principal asked me if there was anything he could do that might convince me to stay, I told him there was nothing he could do because it’s all out of his hands. I rehearsed the list; he agreed. But why was it out of his hands? Because the thirteen six-figure-salary superintendents (almost none of whom I ever met except to speak with the superintendent ten seconds when he visited our school a decade ago and one of the assistant- or associates- when they visited our school as we were coming out of COVID lockdown) take those options out of principals hands. “You should tell them at the next meeting you have that you lost a teacher that you most certainly did not want to lose because of your inability to be flexible in any way,” I wanted to say, but they wouldn’t have listened. We’d all be wasting our breath.

So I’m not working nearly as hard as I used to, but I still feel I’m working, and doing important work at that. Sadly I’m not impacting many of the students who would most benefit from a class like mine (and what I could make it if I did have those at-risk students in the class), but I’m coming to terms with the fact that I don’t have to sacrifice my mental well-being and time for my entire teaching career. I made my sacrifice: time to move on.

But the Boy still has to face all nonsense that drove me out, but he faces it as a student. The endless cycles of benchmark tests with their weak questions drive him to the same level of frustration as they did me. He bemoans how poorly he does on them whether or not he tries, and he speaks of the frustration of hearing his teachers fuss at those who did poorly on the benchmark. “Next time they say that, politely suggest to your teacher that everyone might do better the next time if the teacher could take some time with the class and go over some of the questions the majority of students got wrong,” I decide to tell him when I get home today and listen to him fuss about the latest benchmark nonsense. I know full well that the teacher can do this. I know perfectly well that the teacher himself can’t even see the benchmark test but instead gets a report with the question number, the standard it supposedly covers (and don’t even get me started about how poorly the questions align with the standards), and whether or not a given student got that question right, with a cumulative report for each question and each class. It’s like doing target shooting with a blindfold on and being told only, “You missed. Try again.”

One teacher apparently told him the benchmark is so important that it will impact her decision about which high school class to place him in later this year. “Bullshit,” I want to say when he relates this to me, but I restrain myself and simply tell him that that’s not accurate. But who can blame teachers for doing things like this when everyone from the thirteen superintendents down to the principal, the assistant principal, and the instructional coach all harp on the same nonsense: getting students to make an acceptable score on these tests is equivalent to ending world poverty.

“Don’t tell him not to take this seriously,” K constantly admonishes me, and I do indeed tell the Boy that he should look at the benchmark as must an opportunity to practice with questions like the ones that will be on the end-of-the-year SC Ready test (which, yes, is just as useless but useless at a state level instead of just a district level). But even that is not accurate: the company that creates the benchmarks is not the one that creates the actual test, and while one might think that doesn’t really make a big difference, the quality of the questions from the latter is somewhat improved over the former.

So I am out of the system, out of the haranguing reality of GCS schools, but because E still has three quarters of a school year in middle school (all the testing ramps down in high school: it’s just End of Course exams, SAT, ACT, and AP tests), we still suffer through it together as a family.

Stool Mountain

Do you remember your first love and all the stress and joy that comes from the certain uncertainty that comes with it? Does she like me? Do I still like her? Is she flirting with him? Am I flirting with her? Are we going to make it last forever? Are we about to break up?

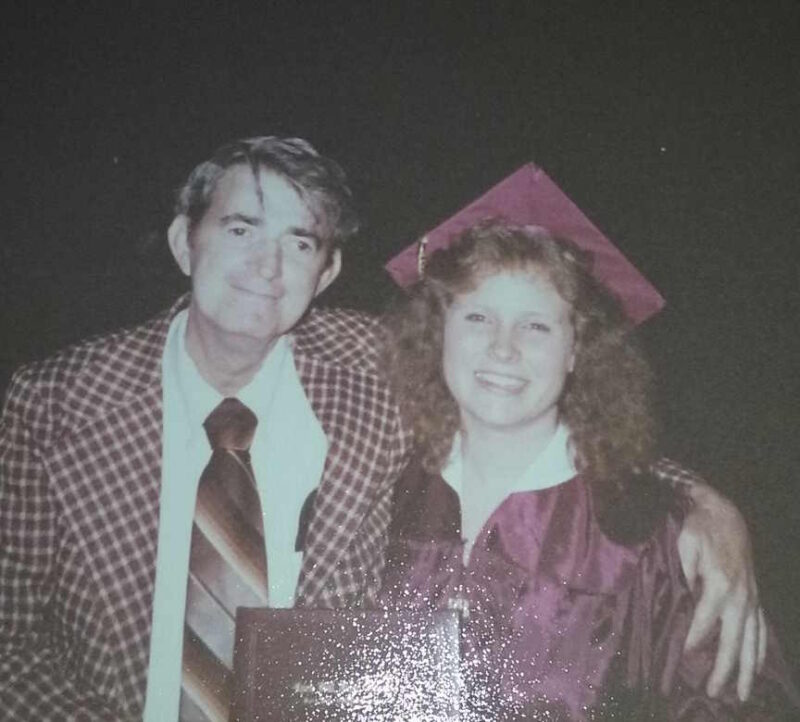

My first love, whom I met at band camp, was Tonya. She lived about two hours away, so our romance was a week together at camp (or less — we didn’t meet that first day) followed by a few months of letters and occasional phone calls. That all lasted three, maybe four months. By the time school started again, we were drifting apart — as if we were every really together.

That was forty years ago now. Tonya and I remained in loose, occasional contact until I was in high school, and we even saw each other a time or two (usually at church gatherings — she was raised in the same sect as I), but I haven’t seen her in over thirty years now, and I really have no clue about her life now. Nor, truth be told, do I really worry about it. Why would I?

But why am I thinking about her now? Because of the Boy and his girlfriend. “Have fun, enjoy this,” we tell him (and her parents probably tell her), “but don’t take it too seriously.” But how can you not take your first love seriously? It’s your first love, after all. Those enormous, overwhelming, awe-inspiring emotions surging through your thoughts continually make it impossible to do anything but take it seriously.

And we all did. We all went through that, “I know he’s the first boyfriend I’ve had, but he has to be the one fate meant for me!” certainty. “I know everyone else breaks up with their first girlfriend, but this is different.” It’s always different because it’s always real. It’s always deep. It’s always comfortable.

Until it isn’t. Until that uncertainty hits. And it always does. And it’s always countered with that certainty. Which is always tinged with that doubt. Which always has a sliver of assurance. That is lined with doubt powered with surety that has been dusted with misgivings.

In short, it’s great until it isn’t, and even when it isn’t, it’s perfectly imperfect.

The Boy is going through all the typical ups and downs of a first love, and we talk about all these things during our near-nightly walk. I encourage him, console him, laugh with him, and sometimes advise him. But mostly I just listen, letting the conversation wind where it will. Sometimes it ends up in band. Sometimes, soccer. Sometimes, something he discovered on the internet.

I try not to advise him too much because often people speak just because they want someone to hear them not necessarily to help them. But when asked, I do give a bit of advice. Yet how can I? Married for twenty years, I have long forgotten about the uncertainties of new relationships; an adult (legally speaking) for thirty-four years, I’ve long forgotten the details of my adolescent loves.

I remember that on-again/off-again uncertainty of it all, but I don’t remember how I dealt with it. I certainly didn’t talk to my dad about it because there was an understanding in our church that adolescent relationships were of little value and might actually hurt your spiritual growth. I honestly kept all my interests, loves, and infatuations from my parents until I was sixteen or seventeen, and it was no longer possible to hide them. Even those early loves, I’m sure they realized, but we never really talked about them.

That’s not to disparage my folks: I’m sure if I’d taken the initiative to discuss any of that with them, they would have talked to me about it. I just always got the sense from sermons and such that I just shouldn’t be having those feelings so young, and if I did have them, I was supposed to master them instead of letting them master me. Sort of purity culture on steroids.

So that’s likely one of the reasons I so treasure my walks with the Boy. That he trusts me to talk to me about these things is something to cherish.

Something else to cherish: a Tuesday-morning hike with your lovely wife of twenty years. Why Tuesday morning? Because I have fall break right now.

“I could take off one of those days, and we could go for a hike!” Kinga realized a month or so ago when we were looking at the calendar together. So that’s just what we did: a new trail up a mountain right beside one of the most-hiked trails in the area, Table Rock. Next to a table, one must have a chair or a stool or something. Enter the new trail: Stool Mountain Trail.

Back on the Bike

My mountain bike has been out of commission for a few weeks now simply because I didn’t take the time to drive it to a shop to see what’s going on. I didn’t know if I’d bent my derailleur hanger, my pully cage, or something altogether different, but my shifting was completely off. It turned out to be the hanger, which the mechanic bent back into shape but warned me the next wreck would be the last: “It will snap.”

I took it out for a ride this afternoon. No wrecks, so no snapping. But a relatively slow ride.

Field Trip

My Uncle

Guests

We’re guests in our current school building. The charter high school with which we are affiliated (indeed, for which we will be the feeder school) is letting us use one hallway to house all 150 of our middle-school students. So none of the facilities are ours. The cafeteria is not ours. The gym is not ours. My classroom is not mine: I’m only using it until our building is completed, and we move in, which is supposed to be some time in the middle of the second semester. March-ish.

While we use their facilities, the teachers we displaced are “floaters.” They have one class here, one class there. always moving from room to room. ”That’s how almost all teachers in Poland are,” I explained to my colleagues, adding the notion of the Polish cohort: a group of kids with whom you spend all day, every single day, throughout high school. “Oh my God! No way!” is the typical student reaction; “I’d hate not to have my own space” is the typical teacher reaction. Both are understandable.

Being a long-term guest is liberating in a sense. I’ve not bothered putting much of anything on the walls. I put up some pictures on existing nails, but I haven’t added any holes that weren’t already there. I’m using the teacher’s desk while mine sits along one wall virtually unused. Everything the teacher, Mr. W, left hanging on the walls is still just where he left them. I leave as much untouched as possible. Liberating.

Yet I’ve already gotten into routines of using certain things that I won’t have when we move. Mr. W has a number of small dry-erase boards, each probably about a foot square, which is great for students to use for notes and such that are not critical but need to be shared with others. He has a hanging divider on the wall where I store six folders (one for each class) that has work in it I need to grade. (All are currently empty: a great feeling.) The chairs are fablous for middle schoolers: there are four possible positions the kids can choose from (and they all make different choices from day to day, believe me). All of that will change when we move to the new school, and while I usually hate change like that, I’ve gone into the year with the understanding that it is by nature a year filled with change. So I’m surprisingly calm about it.

Soccer Practice

The Boy’s team notched a significant win this weekend, beating a previously-unbeaten team, and that decidedly. What does a wise coach do on Monday practice? Run drills? Work them silly? Burpees and suicides? Of course not — he just let them play.

And the sun did a little playing with the clouds as well. That photo looks excessively edited, but I did my best to make it look just as it did when I took it — some of the most brilliant and rich colors I’ve ever seen. Only the ground is too dark…

Sunday Walk

The Boy has joined the Carolina Youth Symphony. Their mission, according to their site:

Our mission is to encourage artistic excellence in a nurturing environment by providing the highest quality orchestral training and performance opportunities to qualified musicians, grades K-12, and make participation possible through many financial aid and work study programs.

CYS Website

Auditions were in May, but since the Boy’s middle school band teacher is one of the conductors for the CYS, he pulled some strings and got the Boy an audition in September.

Practice is every Sunday from 1:15 to 2:45, and it takes place on the Furman University campus in the north of the city. It’s a private university with a lovely campus complete with a lake and its famous tower. So while E plays, I go for a walk.

K and the pup went with us today since she had the free time, and we went for a four-mile walk while the Boy rehearsed with about 50 other local kids.

Of late, the Boy has really become focused on his music. We have an hour-long private lesson for him every Tuesday, and he returns home from that lesson and plays for another half hour or so, usually on the back deck. He told me that someone once shouted “Good job!” at him when he finished playing.

Goal!

It’s not often Emil scores a goal: he plays left back most of the time, so defending is his thing. But the coach put him up front in the second half of today’s game, and he got a free kick.