13

And just like that, we have two teenagers.

Mother’s Day Walk

Upper State Championship

Last Friday

Our lives are filled with unconscious lasts — the last time we do this, the last time we do that. It’s rare that we encounter a last knowingly, consciously, purposefully. Retirement, weddings, births: these might count

Today, I pull into the parking spot I have used for years, shut off my engine, and sigh with the contentment of knowing it’s Friday. We’ll have a respite — some room to breathe. “Only a couple of more weeks of this,” I think, and running the news two weeks’ schedule through my mind, I realize that this is in fact the last regular Friday I will be teaching at this school. Next Friday is the eighth-grade field trip to Carowinds; the following Friday is the last day of school, hardly a normal school day.

Yet, truthfully, even today is not a typical Friday. A large portion of the students are on a band field trip to Carowinds, a theme park in nearby Charlotte, for a competition, and today our PTA is hosting the cooking for students who achieved all As throughout the year, which means several students will be out for a couple of periods. Given that we’re done with testing, none of us are engaged in any rigorous teaching with any of our classes at this point. So the last typical Friday passed some time ago, unnoticed and unacknowledged as so many other lasts.

For someone who likes to wallow in nostalgia as I do, such an epiphany brings everything into sharp focus. I step out of the car determined to notice and to appreciate every little feature of the day.

I cross the parking lot and begin up the sidewalk to the school, stopping at the dip in the sidewalk through which the roadway from the car drop-off line passes. A small grey car passes, but the large white SUV behind it stopped, the driver waving me across. I raise my hand in acknowledgement and smiling in polite gratitude, hurried my step. NEW ADD DETAILS

Up the sidewalk and to the right I turn, stepping through the puddle of dark water that sits continually at the end of the carline colonnade. Like the relatively-newly-redirected carline, this puddle is a new development. It forms from the drops of water falling from the stub of PVC pipe that breaks through the wall, slowly discharging the water drawn from the moist air of the classroom. Most classrooms received a dehumidifier earlier this year to deal with the high levels of humidity that often leave their marks in mold over the long summer. In the few short months the dehumidifier’s discharge has been dripping in that spot, a stain has formed and a small rise of sediment has formed, the beginnings of some kind of modern stalagmite. It’s only taken a few short months: who knows what it will look like after a few more years? In the past, I might have thought, “We’ll see over the next few years,” but I won’t see.

As I continue up the sidewalk, I greet a couple of students as they get out of their cars. There has always been such diversity in our population, and that’s clear from the cars in the line. One student gets out of a beat-up clunker; the next gets out of an expensive Mercedes. This diversity has always been a charm and a challenge at this school. I’m likely to have less diversity at my new school, and since it’s a charter school that one must apply to attend, I’ll likely have few if any at-risk students. I’ll miss that, to be sure, but I won’t at the same time. Working with kids saddled with trauma is exhausting, almost to the point of trauma itself.

After I check my small cubby of a mailbox, I head down the hallway to my classroom and pass two of our Spanish teachers, a gentleman from Columbia and a young lady from Peru. They stand in the corridor chatting in Spanish. As I pass, I understand a word or two but nothing more. Suddenly I remember doing the same in the small high school in Poland where I taught for seven years. “That’s what we must have looked like standing in the hall chatting in English,” I thought.

Leaving that school for the first time in 1999 was so wrenchingly difficult. Not knowing when I’d be teaching again and already missing the adventure of living abroad, I sat numbly in a small bus with the village drifting by one last time as I headed to Krakow to leave for the States. I knew that ending was coming, too, but the uncertainty that followed was awful. Now, I know exactly what I’ll be doing next year, and knowing I’ll still be in a classroom transforms my departure into a transition.

Shortly after I enter my room, my first student arrives. A young lady in my homeroom and honors class, EC is a conscientious student who stresses entirely too much about getting everything right. She puts her materials down and begins typing something on her computer.

“EC, did you realize that this is your last regular Friday in middle school?”

She smiles. “Yes, sir,” she began, always such a polite Southern girl. “Julie, Alison, and I were just talking about that last night.” Girls after my own sentimental heart.

“We so often move through lasts in life,” I continue, “and we don’t even realize it’s the last.”

“Yes, sir,” she replies, still smiling.

“It’s good to be conscious of and acknowledge those lasts,” I say. “To enjoy them. To cherish them. To savor them.”

“Yes, sir,” comes the response. EC’s smile suggests that she is just being polite, and since no one wants a lecture at eight in the morning, I let it go. Still, it’s heartening to see someone so young being introspective about life instead of just gliding through it without thought. Of all my students, I would have put EC high on a list of potentially self-reflective students.

A few moments later, Tonia, another student in EC’s honors class, bounces in. Tonia has always been all smiles. She, too, is somewhat introspective: she has a charming nickname for herself whenever she does something she regards as, in her words, stupid — Ton-key Donkey. It’s rare that a middle school student can be so freely and jocularly self-derogatory. It suggests a maturity that is rare in middle schoolers, a maturity that makes a student stand out, makes a student shine.

“Did you see my email, Mr. Scott?” she asks with her usual lilt.

Loading my email, I explain that I haven’t had a chance yet. She starts waving her hands to warn me off.

Tonkey-Donkey messed up!! I submitted the comprehension questions and got a 78% on them! I am confused about what I could have gotten wrong and I’m worried about how much it’s going to bring my grade down. Is there anything I can do to bring my grade up? Thank you!

As she begins explaining, I exclaim, “A 78!?!”

She buries her face in her hands in playful, mock (but not entirely so) shame. “I know! I can’t believe it. I don’t know what happened. I thought everything was fine and then I submitted and saw the grade. A C! A C! Mr. Scott, I never get Cs. Ever. One time, okay, one time, but the teacher gave me a chance to raise the grade. Some students might get a 78. I don’t get 78s! Ever! It’s going to bring down my grade so much! This is awful! I couldn’t sleep last night because I was worrying about my 78. Well, 77, but it’s 77.5, so you’ll round that up to 78.” All of this flows from her in what sounds like one breath as she hops from one foot to the other and gestures wildly with her hands as she explains the looming tragedy.

Together, we look at the questions she got wrong. They’re questions about the end of To Kill a Mockingbird, specifically about how the sheriff, Heck Tate, tampered with evidence to make it look like Bob Ewell fell on his knife. Students never get the intricacies of that passage, and we’ll go over it once everyone is done with the book.

“I thought I’d set the value of those questions to 0 so they don’t affect the kids’ grades,” I think, almost muttering out loud to myself and making a note to go back and change that value.

“Is there anything I can do to raise my grade?!” Tonia begs.

Such a sweet child, and such a wonderful student. She’s in my class because her mother requested it. In truth, it’s because I requested it. Tonia’s little brother played on E’s soccer team a couple of seasons ago, and Tonia’s mother asked if it would be possible to request she be in my class and how she might go about doing that. “I’ll just put in a request for her with the counselor,” I said that spring afternoon. Had I known Tonia, I would have made the request without any request from her mother, so charming is Tonia.

As we’re talking, another girl from a different honors class comes in to tell me that she’s completed an assignment that is marked as “Not handed in” (NHI in our district parlance). She’s not worried about the grade as much as the fact that she never — never — gets NHIs. She’s okay with me changing it to GFA (Grade Floor Applied), which will have the same effect on her grade as “NHI” but without as much of the stigma she’s attached to it.

Most of my students next year will be like this. There will be few (if any) students who have a majority of NHIs in the gradebook. District policy mandates that NHIs count as 50s rather than 0s. In other words, ten points from a passing grade. The thinking is reasonable: if you have an extremely low grade from zeros, it’s likely to discourage you from doing anything about them. There’s no way to come back from that. With 50 as the grade floor, students can recover. The problem is, at the high schools, there is no grade floor. These 50s will suddenly be 0s, and kids who skirt by with 60s as a result of the middle school grade floor will find themselves with grades in the thirties or forties in high school. The common sentiment is that the district is setting them up for ultimate failure with this grade floor, but there’s nothing we can do but comply.

“There will be no 50 floor at this school,” the principal at my new school announced at the in-take meeting last Saturday, and this announcement received rather vigorous applause from the parents.

As these virtually-simultaneous conversations bounce along, I notice two of the four Muslim students on our team have come in to join the two in my homeroom. Three of the girls are from Afghanistan; one is from _______. They chatter away in a mix of languages. The ______ student explains that she can understand a bit of the Dari the other girls speak, and since Arabic and Dari use the same script, she can sound out the written language, “but I can’t say anything,” she laughs.

One of the girls, Asmaan, comes up to discuss a small assignment she has. New to America, Asmaan speaks very little English. This is, in part, because of her lack of experience with the language, in part, because of her reticence to speak. She’s a quiet girl no matter the language, and that is obvious when she begins discussing her assignment. Her class is reading The Diary of Anne Frank, and I procured for her a Dari version of the original diary, which she is reading on her own. My assignment to her was to find three ways that she and Anne are similar and two differences. Asmaan shows me her Chromebook, which is open to Google Translate, where she has written in Dari to translate to English: “Anne is very talkative, and I am not.”

“Yes,” I begin slowly, “but I want you to say these differences. To speak.”

At first she misunderstands, feeling confused about the parameters of the assignment. Once we clear that up, she heads back to her desk to practice saying her handful of sentences.

I wonder at the similarities and differences she will find beyond the obvious. As a young Muslim girl who wears the hijab, she stands out and in some opposition to the society around her, much like Anne. Does she see that similarity? Even if she does, will she willingly admit it?

The first of two honors classes begins and students form their literature groups. All of my classes are working in independent literature groups, but most of the

During class, Jessica, confused about one of the questions, comes to discuss it with me. The question is about one of the passages in Mockingbird that most students miss:

Mr. Tate reached in his side pocket and withdrew a long switchblade knife. As he did so, Dr. Reynolds came to the door. “The son—deceased’s under that tree, doctor, just inside the schoolyard. Got a flashlight? Better have this one.”

The question is meant to see if students made the correct inference about what Heck Tate was about to say to Dr. Reynolds: “How does the conversation about the attack change the reader’s opinion of Heck Tate?” The correct answer is “We realize he hated Ewell just as much as everyone else did,” but most students struggle with that passage.

It’s not the only scene from the novel that students struggle with. Students in the next period are trying to figure out what the three versions of Bob Ewell’s attack on the children could be. “There’s what Atticus thinks happened,” I explain every year, “then there’s what Heck Tate is going to say happened, and finally, there’s what really happened.” The first two are fairly straightforward; the third, the truth behind Tate’s lie, eludes students and always has. The key to the mystery is actually in the passage above, which is the real reason I ask students to re-examine it.

Mr. Tate reached in his side pocket and withdrew a long switchblade knife. As he did so, Dr. Reynolds came to the door. “The son—deceased’s under that tree, doctor, just inside the schoolyard. Got a flashlight? Better have this one.”

“I can ease around and turn my car lights on,” said Dr. Reynolds, but he took Mr. Tate’s flashlight. “Jem’s all right. He won’t wake up tonight, I hope, so don’t worry. That the knife that killed him, Heck?”

“No sir, still in him. Looked like a kitchen knife from the handle. Ken oughta be there with the hearse by now, doctor, ‘night.”

Mr. Tate flicked open the knife. “It was like this,” he said. He held the knife and pretended to stumble; as he leaned forward his left arm went down in front of him. “See there? Stabbed himself through that soft stuff between his ribs. His whole weight drove it in.”

Mr. Tate closed the knife and jammed it back in his pocket. “Scout is eight years old,” he said. “She was too scared to know exactly what went on.”

I want students to notice that little detail, the switchblade. Good writers do not just drop details in a scene for no reason. The switchblade must be somehow significant. To make sure readers see that, Lee refers back to the switchblade a few pages later:

“Heck,” said Atticus abruptly, “that was a switchblade you were waving. Where’d you get it?”

“Took it off a drunk man,” Mr. Tate answered coolly.

Sharp readers realize that it is in fact with that switchblade that Ewell attacked the children, that Tate found Ewell with a kitchen knife in his gut and a switchblade in his hand making it impossible to suggest that he fell on his own knife, thus shielding Boo Radley from the town’s attention.

Next week, we will go over these passages as a class, and with a gallery walk I hope to nudge the students to these realizations. These are honor students: they will continue putting forth their best effort even knowing that grades and testing are all behind them. Indeed, that is, in large measure, why they are honor students: they’re really no smarter than most; they’re just harder working.

Sixth period students are finishing up the play version of The Diary of Anne Frank in literature circles, and since some students are further ahead than others, some students only have a few minutes of work on this Friday afternoon. A couple of Latina students, Valentina and Gabriela, come up to talk to me about a problem one of the girls is having with one of the Latino boys in class. Valentina has her Chromebook open with a translation of what she wants to say.

“No, no!” I scold her playfully. “Take that back to your seat and learn to say it.”

Valentina heads back to her seat, but Gabriela stays at my desk.

“What’s this about?” I ask Gabriela. Of the four Latina girls in his class, Gabriela speaks English the best and often translates for the other girls when sticky language issues arise.

“Luis keeps saying stuff to her, calling her names,” Gabriela explains.

Finally, Valentina, who’s been practicing in the back corner, comes back and explains what’s going on.

“In English or Spanish?” I ask her.

“In English and Spanish,” she explains.

Though I rarely do so, I ask Gabriela to translate for me: “Unfortunately, at your age, a lot of kids just act childishly. It’s best just to avoid such students.” I know it’s not the best solution, but how else can I deal with one student simply being childish to another? “Someone has to be the adult,” I conclude, and Valentina nods.

I feel a little guilty about my non-native English speakers, or as the common jargon labels them, MLs, mult-linguals. I never feel I’ve done all for them I could have. Asmaan is also in this class, and I feel I could have done so much more for her. I blame the district in part: dumping these kids into regular classrooms with very little direct English language instruction seems terribly unfair and awfully ineffective, but I have no say over district policies developed in turn from state department of education policies that seem at best discriminatory. But that’s just an excuse: I could have done more, and I, often tired and frayed, simply didn’t put in the extra planning and preparatory time necessary for such students. I could, in turn, also push this onto the district: we have so many required meetings and so many administrative responsibilities (many of which feel completely arbitrary and useless) that our planning time during the day disappears into a seemingly-endless stream of meetings and surveys. In the end, I must face it: I could have done more.

Seventh period files in, and noticing the sound meter still projected on the Promethean Board from the last period, several of them begin screeching and whooping to see just how high they can make the meter go. This maturity disparity often differentiates the honors classes from the on-level classes, and this difference continues into the class itself. Students are to work in self-directed reading groups to complete The Diary of Anne Frank, and the more mature students do just that while the less mature students, the ones often with behavior issues, mountains of NHIs in the grade book, and a long string of disciplinary referrals, use the time to entertain themselves with conversations and silliness. It’s the end of the year, though: testing is over, and I have already drained myself with this class. I make the decision to let them be.

Karma will catch them, I assure myself. In time, they will have to find a job and support themselves, and they will find it difficult to keep a job with their inability to stay focused and on task for more than (with some students, literally) ten to fifteen seconds. I don’t want their lives to end up like this, and I’ve repeatedly sketched out the contours of their futures if they don’t develop better habits, but I’m tired: even Sisyphus could push only so hard.

Aside: it was eighteen years ago today that I accept my current job.

First and Only

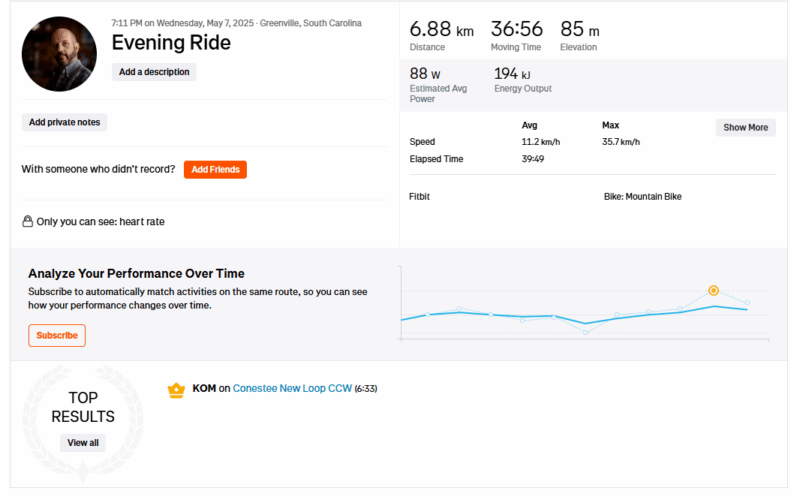

Yesterday, E and I went for a short mountain bike ride: one quick loop each around all three paths at our nearest mountain bike path. There’s a new loop, we took it. Naturally. It’s mostly gravel and packed dirt, but there’s one paved section. I picked up the pace; E matched it; I accelerated; he matched my speed — soon, it was an out-and-out race.

When we got home, and I checked the stats on Strava, I saw that we’d gotten the KOM for that new segment. Granted, only four people have ridden it, but still — a King of the Mountain for a Strava segment? That’s what legends do!

So this evening, I did the logical thing: I went back and rode it again, taking almost 45 seconds off the KOM.

It will fall soon enough. A fat man on a cheap bike (my Strava profile tag line) can’t hold a KOM for long. But the point is, I never thought I’d get a KOM…

Conestee Turtle

Closing In

We’re in our final three weeks of school — my final three weeks at Hughes. My testing is over: we had three days — three days — of English testing (two reading, one writing). My grades are almost done: English 8 students have one more grade while English I Honors have three. Everything is winding down.

And those three weeks are hardly full weeks: we have another day of testing (math — poor sixth-grade students have two more days of testing because they also have a science test); we have a field trip next Friday; our last two days are half days; I’m missing one day for L’s graduation. And we’re done with Monday. So that means we have about ten more regular days of school. “Are you excited about next year?” seems to be the common refrain from my colleagues, and I freely admit that I am at such peace with this decision that I don’t think excitement is the emotion I’m feeling: confidence, surety. It will be a good thing.

This Saturday, we had the intake for students at the new school, so I got to meet a lot of students and parents. As I told them the plans I have for this class, parents continually told me, “That sounds like a very valuable class.”

Yet every now and then, it really hits me what I’m about to do. I’ve taught at that school for eighteen years now. Seventeen of those years I’ve been in the same room. I’m comfortable there. I have no surprises there. But surprises can be a good thing. I hope to have many of the next year.

We’re also closing in on L’s graduation (May 20) and her departure for college. We’re ordering things (a new laptop that’s actually more powerful than our desktop), planning things (a graduation party that will last an afternoon and evening), discussing things (upcoming exams, upcoming travel), and getting used to the idea of her being gone (not really).

And then there’s the Boy: he’s got concerts and competitions for band; he’s got his own testing worries to stress about (why do we do this to kids?); he’s got a burgeoning social life for which we provide transportation. All this as he closes in on his final year as a middle schooler.

Grad Pictures

Polish Festival

Final Competitor

Conestee Dam Renovation

Our Girl

Saturday

Thursday Badminton

Easter 2025

Holy Saturday 2025

Good Friday 2025

Holy Thursday and Papa’s Birthday 2025

Outdoor Concert

Can’t embed E’s latest concert. Might not even be able to watch it…