A friend posted a link some time ago to Anthony Esolen’s article at InsideCatholic.com about The Sound of Music and how it would resonate (or rather, fail to resonate) with today’s culture. The article begins,

Recently my family and I watched The Sound of Music for perhaps the twelfth time — probably the last great musical that Hollywood ever produced. It made me wonder if I could list the reasons why such a movie could not now be made. These reasons I offer below; but it seems to me that they can all be united under the single assertion that the intellectual, imaginative, and emotional palette of the American people has suffered a terrible constriction, a reduction to the tedium of lust and greed and the thirst for power. It is not so much that Hollywood would not make a movie like The Sound of Music as it is that the people themselves would be hard pressed to understand it.

Inside Catholic

He lists a number of reasons:

- The movie takes for granted that some things are holy.

- There is such a thing as innocence — and it is not the same as ignorance.

- There are such things as children, thank God.

- There are such things as boys and girls, and men and women.

- Today, no one can sing. No one knows why people ever sang.

Many of these reasons are fairly convincing, and all of them are clearly argued (even if one doesn’t agree with the conclusions).

I myself watched the film again a few weeks ago, and I tried to imagine my students’ reactions to the film. Much like Esolen, I came to the conclusion that many of them would find it incomprehensible. There’s one more reason, though, that Esolen hints at but never directly discusses. Most contemporary young people would not get the gist of the film because the idea of submission and respect toward authority (even when it seems unfair) is completely foreign to many of them.

The first time such respectful submission occurs is when the abbess suggests to Maria that monastic life might not be where God’s leading her. Maria protests, giving all the reasons why she she feels she must stay. She grows animated, slightly frustrated, and very insistent. The abbess brings her to complete silence simply by calmly saying her name: “Maria.” The young Maria grows silent instantly, demurely responding, “Yes, reverend mother.” And that’s it. The end of the discussion.

Many young people today would not respond thus to an adult no matter who the adult was. They have rights, see, and they are equal to adults in every way — except paying bills and providing for a family. Many would see Maria’s reaction as cowardly, as a lack of self-respect. Others would simply say, “I’d just turn around and walk off…”

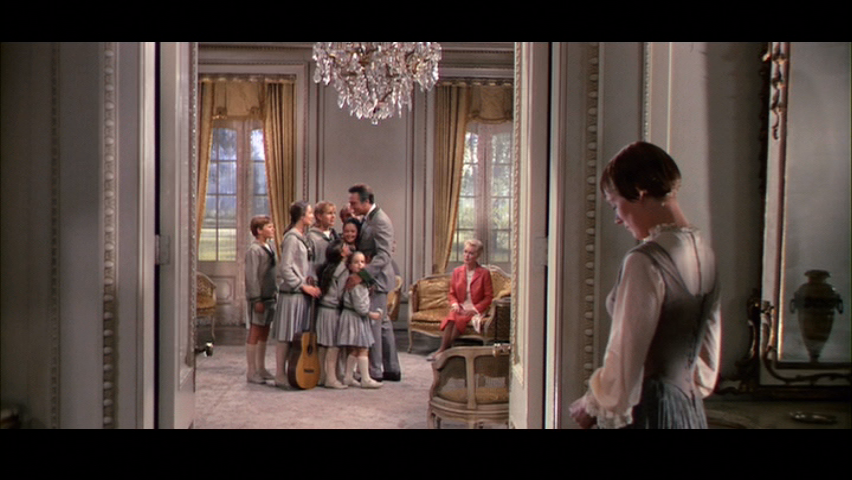

The next time we see this type of submission it is even more tellingly dated. Captain von Trapp blows his whistle to summon the children, who form a straight line and march down the staircase in time to von Trapp’s whistle’s chirps. For most intents and purposes, they’re in the military, and that’s the point: no warmth, no real family ties, just the appearance of discipline.

Maria is horrified, and rightfully so. It is the one time she truly stands up for herself.

I could never answer to a whistle. Whistles are for animals, not for children. And definitely not for me. It would be too humiliating.

Clearly, she is also defending the children against humiliation, actual and potential. She gets away with it, but not without von Trapp commenting on it. But the children? They’re undoubtedly humiliated by the treatment, and they long for a true relationship with von Trapp. Indeed, that is the whole point of the film. But there is no sign of disrespect, only painful hope in the children’s eyes. “Perhaps if we get it right, Father will notice us,” their body language seems to say.

I’m not suggesting that we go back to a time when children were meant to be seen but not heard. However, the other extreme is too prevalent today.

The children long for attention from their father, but how do they get it? Through insolence? Through rebellion? No — by playing childish pranks on the nannies hired to care for them. Many attribute student disrespect to attention-getting measures. Perhaps that’s true. Yet the need to make such a hypothesis is just more evidence of the incomprehensibility of the film. Today’s neglected children go about getting attention from adults in an entirely different manner than in the idyllic times of pre-war Austria.

Another scene that might well be almost impossible for modern viewers to understand is when the children fall into the water after one of their day trips. Maria has gained the children’s trust, and they show their childlike nature around her. There’s mutual respect and even love. Von Trapp steps back into the scene with his whistle, and all returns to “normal”. The children snap to attention and grow silent immediately.

If there is ever a time in the film to protest their father’s callous behavior, this is it. The children could protest about their treatment, pointing out how much they’ve learned with Maria and reminding their father that they are, after all, just children. Indeed, they fell into the water due to their childlike excitement at seeing their father: they all stand excitedly, rock the boat, and fall in. Von Trapp begins by yelling and humiliating them, but the children say nothing. Not even a respectful, “But Father…” Not a word.

Again, this is not a model of my own parenting, but such complete submission to a parent (or any other adult) is, in my experience, a rarity these days.

It is also at this point that the only semblance of disrespect appears: Maria tells von Trapp the truth about his children and their longing for him.

She finally sheds her modest submission and stands up, not for herself, but for the children.

von Trapp: Is it possible, or could I have just imagined it? Have my children, by any chance, been climbing trees today?

Maria: Yes, captain.

von Trapp: I see. And where, may I ask, did they get these. . . .

Maria: Play clothes.

von Trapp: Is that what they are?

Maria: I made them from the drapes that used to hang in my bedroom.

von Trapp: Drapes?

Maria: They have plenty of wear left. We’ve been everywhere in them.

von Trapp: Are you telling me that my children have been roaming about Salzburg dressed up in nothing but some old drapes?

Maria:And having a marvelous time!

von Trapp: They have uniforms.

Maria:Forgive me, straitjackets. They can’t be children if they worry about clothes

von Trapp: They don’t complain.

Maria:They don’t dare. They love you too much and fear–

von Trapp: Don’t discuss my children.

Maria:You’ve got to hear, you’re never home–

von Trapp: I don’t want to hear more!

Maria:I know you don’t, but you’ve got to! Liesl’s not a child.

von Trapp: Not one word–

Maria: Soon she’ll be a woman and you won’t even know her. Friedrich wants to be a man but you’re not here to show–

von Trapp: Don’t you dare tell me–

Maria: Brigitta could tell you about him. She notices everything. Kurt acts tough to hide the pain when you ignore him, the way you do all of them. Louisa, I don’t know about yet. The little ones just want love. Please, love them all.

von Trapp: I don’t care to hear more.

Maria: I am not finished yet, captain!

von Trapp: Oh, yes, you are, captain! Fraulein. Now, you will pack your things this minute and return to the abbey.

Yet she says not a single word about how the captain treats her. Her protests are completely selfless.

Of course Maria doesn’t return to the abbey, just yet. Von Trapp hears the sound of music — literally and figuratively — and the music mends his wounded soul. She has saved the family, yet remains on the periphery, by her own choosing. It’s a private family moment, and it’s not her place to intrude. In short, it’s not respectful.

Many today don’t have this sense of respect so clearly illustrated in the film. Respect is not something one has automatically by being an adult or being in a position of authority. It’s something to be earned, and any perceived disrespect — a teacher telling a student to stop talking, for instance — provides free license for whatever (verbal language or body language) the individual might deem necessary to “defend” oneself.

Respect has become a token, if that, and in such a world, a film filled with unquestioned, unconsciously-given respect is utterly incomprehensible.

Bravo!

This is something I think about quite a lot as I watch children and adults develop patterns of interaction here. Respect for age and authority are not New World values. This country was not built on them and indeed, the adventurous spirit here has always applauded individualism over obedience. And perhaps that’s a good thing. But there is the fallout. It seems to me that kids here have a very hard time participating in social events where they are of secondary importance — where they have to amuse themselves or listen to the voice of someone whose authority trumps theirs. I’ll never forget a time when I hosted a brunch in the neighborhood. An 11 year old son came over with his parents, but he quickly became bored. He literally threw himself on the floor and demanded attention. I could not believe it — the parents, in the mildest of ways suggested that he get up and tell us about some story or other. Uff! Many have said that I had a very “European” approach to childrearing. I’ll agree in this way: I would have been horrified if my kids had entered an adult gathering and demanded anything at all. To this day, I believe in at least a superficial level of respect. In school as well. Students who feel compelled to constantly challenge decorum and rules of behavior are, it seems, at an overall disadvantage when they fashion their own futures once they’re in the “real world.” (Even as I understand that you have to have a firm moral compass that permits you to challenge authority when it puts you in the position of causing harm to others.)