Today was a day focused in some ways on the Boy. He had his three best friends over for the day (the twins plus, you might say), and we decided to go to the pool for the afternoon. This was the pool in which we had a membership some years ago, the first (and only) year the Boy was on the swim team, so I was familiar with it had had all the appropriate expectations: lots of kids, lots of yelling, lots of chaos.

I had no desire to bob about in a crowded pool, and swimming laps would have been out of the question, so I took something to read and relaxed by the pool in a covered area. Taking a break from reading, I glanced up at a newly-installed support pole supporting the corner of the structure. I noticed there were no bolts at all securing the support to the concrete pool deck. “Surely there’s some kind of support at the top,” I thought. Nope. An entire corner of a structure bearing down on a completely unsecured support: seems safe enough.

I checked the other four supports: the one in the other corner of the open area had two bolts at the two and two at the bottom. Two at each end is certainly better than none, but not quite sufficient considering each end of the pole required four bolts. Of the other two supports, one had a single bolt in the top but none at the bottom (though there was a zip-tie through one of the lower bolt holes) and the other had no bolts whatsoever. So of the thirty-two bolts required for the four poles, there were in fact five bolts in place. Basically, whoever replaced the likely thoroughly rusted supports with these new, shiny poles is relying strictly on gravity to keep the structure safe.

This clear code violation is open view, impossible not to notice. How has it stayed this way so long? Is there a plan to remedy this? Has someone spoken to the local building inspector about it? Has anyone else even noticed?

For a brief moment, a scenario runs through my head: I decide to contact the local building inspector and report the condition. To make things clear, I decide to include photographs of the supports. As I snap pictures with my phone, someone notices what I’m doing and takes umbrage. “They might close down the pool!” the individual complains. A confrontation ensues.

In the conservative South, there seems to be a general distrust of anything that even hints of governmental control, and it’s often tied back to religion in some way or another. Environmental regulations are classified as government overreach and a violation of the divine mandate for humans to use the earth as they themselves see fit a la Genesis. Rumors of coming vaccination requirements during the pandemic had people speaking of apocalyptic visions and the antichrist. And the closing of churches during the pandemic? That was evil itself: Satan trying to bring the gates of hell against our freedom to worship our Lord and Savior. “We’re a freedom-loving people!” This all soon devolves into talk of the supposed Deep State and affirmations of the necessity to re-elect Trump to clean the swamp and defeat the fascists of the Deep State, not to mention fascist building building inspectors.

I am, of course, exaggerating, but just barely.

So to avoid such confrontations, I waited until just before we left to take the pictures that I will send to the neighborhood’s residential board members…

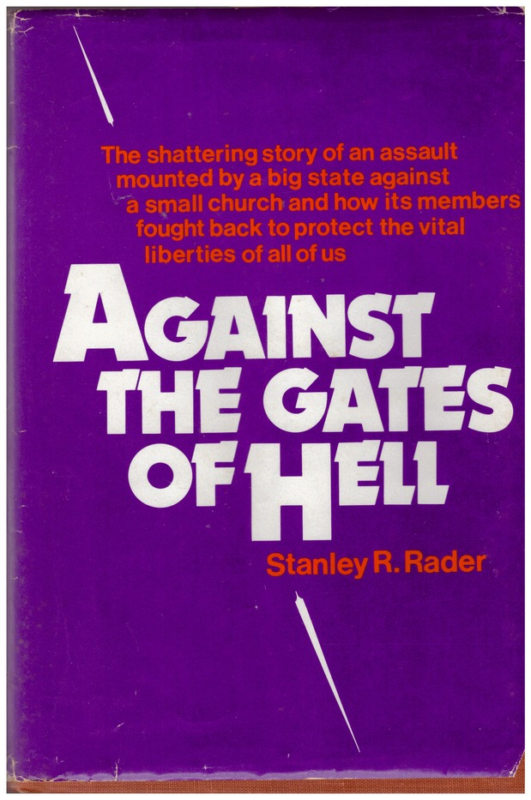

The reason I went down that rabbit hole, in part, has to do with my most recent reading, something I downloaded from an obscure website that specializes in materials from the sect I grew up in. The blurb on Good Reads:

On January 3, 1979, without warning, the attorney general’s office of the state of California struck a hard blow at the Worldwide Church of God. Responding to vague complaints from a few dissident former Church members, the attorney general, in the wake of the People’s Temple tragedy, rushed to court asking that the courts throw the Worldwide Church of God into receivership. It was almost like a military maneuver; the attorney general’s deputies charged onto the campus of Ambassador College in Pasadena, the Church’s headquarters, ordering employees out of the building, demanding church records and actually firing Church officials.

Within hours and then days, the campus swarmed with Church members who poured into Pasadena to fight back. They picketed, they surrounded the buildings, and they swore never to yield to an anti-constitutional assault; at the same time, their leadership was petitioning the courts for relief.

The Church, led for over one half-century by Herbert W. Armstrong, its Pastor General, has been a leader in spiritual affairs in the United States and throughout the world. From his home in Tucson, the 87-year-old Armstrong urged his followers to fight back. Eventually, the membership prevailed. The receiver and his assistants, costing thousands of dollars a day which the Church had been forced to pay, were removed by the courts.

The fight continued into the highest courts of the land. It is the traditional story of stave versus church and of the indignation that erupts whenever the state attempts to deny the rights of a legally constituted church.

This book is the dramatic story of that battle and with it, the story of the Pasadena-based Worldwide Church of God and of its patriarch, Herbert W. Armstrong. It is also the constitutional-issue account of a particular small, but determined, group fighting the powerful state which applies to all who care deeply about our civil liberties. For, had the state of California won its battle and destroyed the Worldwide Church of God, it would be open season for any state to do the same to any other church anywhere in the United States.

I was six when all that happened, and I remember Papa reading Rader’s book to the family on Friday nights. At the time, I viewed the church as a victim; as I grew older and more critical of the church, I took a different view, thinking perhaps the State’s move, while too much, was justified. After all, there was a lot of spiritual abuse going on, and the leaders of the church used that abuse to enrich themselves.

Reading Rader’s book, though, I see the whole thing was a mistake. Not because I don’t think the scrutiny was unjustified — it certainly was. But it galvanized a lot of people and helped reenforce the notion that churches are untouchable because of their constitutional protections.

As an aside, Rader appeared on Sixty Minutes opposite Mike Wallace during all this, and he got quite heated when Wallace played a taped conversation between an informant and Herbert Armstrong: