I gave my students an article of the week about the Kaliningrad House of the Soviets, an administrative building constructed during the Soviet era but never occupied because of structural issues.

The structure was redolent of all the communist-era buildings I’d grown so accustomed to in Poland, and like the Palace of Culture and Science in Warsaw, it has its detractors:

Even architects who admire the original, bold design in a mixture of the modernist and brutalist styles concede that the House of Soviets fell short of its promise as a symbol of the Soviet Union’s control over formerly German land captured during World War II.

Instead, the building became emblematic of flaws in the Soviet system, as shoddy construction and structural defects meant it could never be occupied.

As a result, it’s to be demolished in the spring of this year. As might be expected, this provokes mixed reactions:

“It’s like a monument to the Soviet Union we should keep,” said Yevgenia Kryazheva, a waitress at Tyotka Fischer, a German restaurant with windows overlooking the House of Soviets. “I don’t like how it looks,” she conceded. But “people like things with defects. It’s ugly, but it’s ours.”

I can understand that reluctance to let go of a socialist realist architectural past: I’ve experienced it myself.

The bus station in Nowy Targ was an ugly structure, a mix of traditional wood building materials and the angular modernist look of the seventies. The roof angled upward to the front-right corner of the building, and off the back-right and front-left corners jutted buttress-like structures that likely served no functional purpose but were intended to give that exact impression as if the building were somehow cantilevered at odd angles and but for those buttresses would collapse. The back right corner of the building was the main waiting area, and it was enclosed in glass that rose two stories above the floor, giving the waiting area an open, light-filled feeling when first constructed.

The right-front corner of the building had a second story to serve as offices or shops. There might have been a small cafeteria on the second floor, but I can’t really recall. The ticket booths were on the left-front of the ground floor.

From the back jutted a covered area to wait for busses. Local-haul busses parked on the left; long-haul busses pulled up on the right.

When I first entered the building in 1996, it was a little more than twenty years old, but it already looked much older. The style dated it, but the grimy windows and weathered wooden exterior made it look at least a decade older. The originally-light-hued wood siding had turned dark brown from age and dirt. Spruce trees had grown up around the back-right corner, concealing almost entirely the two-story windows. A fast-food kiosk built behind the building concealed the rest of the windows. At the far end of the line of bus bays was another kiosk that sold CDs and cassette tapes of disco polo, essentially the country music of Poland.

The spacious two-story waiting area, originally conceived to be filled with light, was dark and dirty. Kiosks along one side took up at least half of the waiting area’s original space, crowding passengers into a small dark corner The windows were always streaked with the running beads of condensation formed by the temperature difference in winter, and those streaks dried in the summer to form a dirty haze. There was always a Roma family or two in the waiting room: a mother and a couple of children, sometimes begging, sometimes just waiting.

Even on a bright summer morning as passengers sat watching cleaning ladies scrub down this or that, the Nowt Targ bus station felt grimy and tired, as if a film of dirt had bonded permanently to the surfaces of the building. The dated architecture did not help: with the Berlin Wall history and Communist rule nearly a decade in the past, the socialist realist angles and materials simply made the building feel like a relic of an oppressive past.

In winter, there were mountains of snow around the back of the terminal where the busses parked, mountains that steadily turned became covered with flecks of gray and then black as the coal smoke particles from the air and the particulate matter from the bus exhaust settled onto the snow. Puddles formed where the busses had crushed the slush and enough mid-day warmth had melted it further. Passengers performed the same operation as they walked here and there, forming a slush on the covered walkway that ran down the middle of the bus loading area. By December or January, all those puddles turned to dirty ice challenging all but the surest-footed passengers.

Waiting inside was always a risky decision. Most passengers stood around the bay from which their bus was to start, so waiting inside might ruin one’s chances of getting a seat once the driver pulled his bus into the slot, opened the doors, and began boarding. This is not to say one would not have a spot on the bus: there was standing room in the aisle, but it was never pleasant to be standing with one’s shopping spread out all around one.

In truth, it was never really even necessary to go into the bus station. Drivers sold tickets on boarding the bus, and there were far more pleasant places to wait for the bus. Within a couple of blocks, there were several restaurants with hot tea and cleaner surroundings.

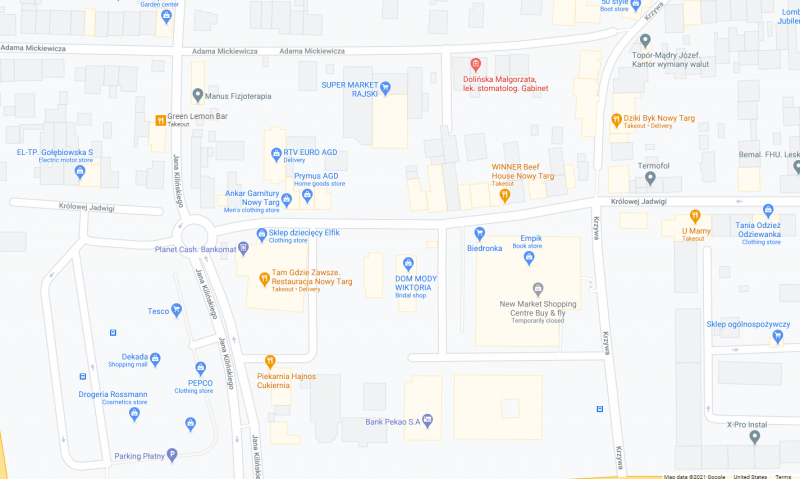

Yet it still served as a landmark for me. Heading home after a long day of shopping in Nowy Targ, trudging through snow and slush, I always felt a wave of relief when I turned left from Queen Jadwiga Street on to Jan Kilinski Street, approaching the bus station from the back. The lines of busses, the piles of dirty snow, the people milling about waiting all signaled that I was just about home.

When I was back in Poland in 2013, it was all gone. I was hoping to take some pictures inside and out, to wallow in nostalgia, but it was not to be.