The Boy claims he hates — hates — reading. It’s hard. It’s exhausting. It’s boring. Yet there are some strange quirks about him.

For example, he loves reading — if someone else is doing it. He will sit for hours and listen to you read a book to him. One of his favorite things to listen to is an audiobook.

He also enjoys certain books. The Dog Man series is an eternal favorite for him.

Most strikingly, he scores very high on his standardized reading tests — in the 90th percentile as I best recall, which means he’s very good at reading for his age.

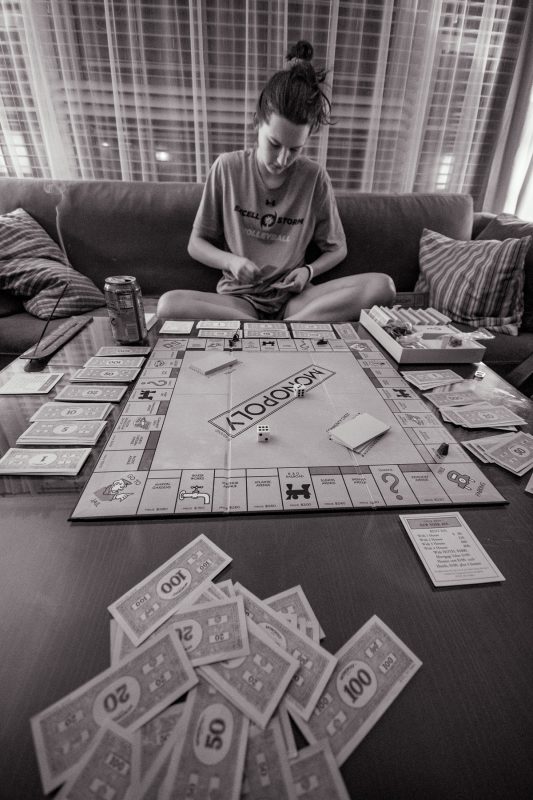

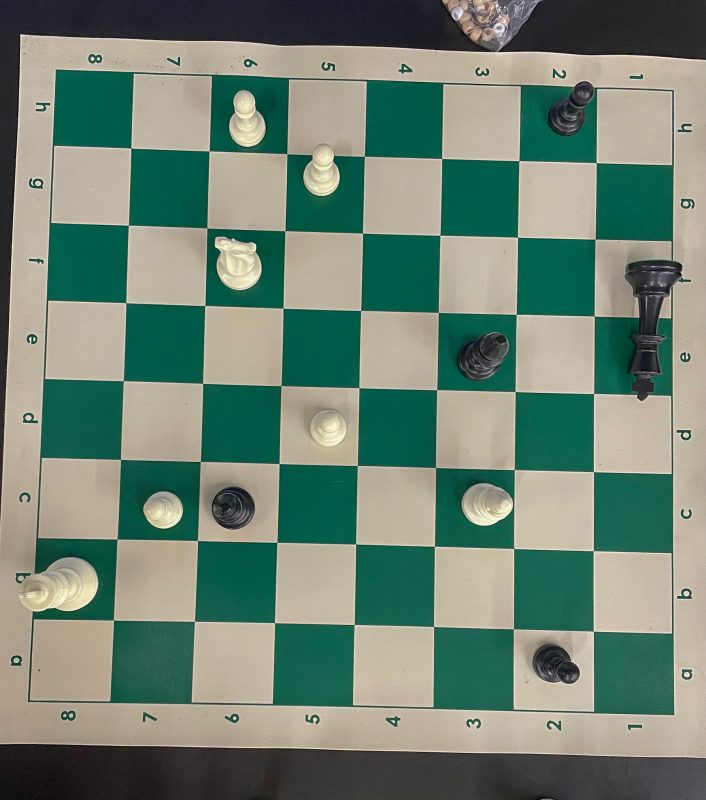

But we still have to force him to get his nightly twenty minutes of reading in. Yet he was so engrossed that he didn’t even notice I’d snapped this picture.