We started working on poetry this week. I always begin with the same poem:

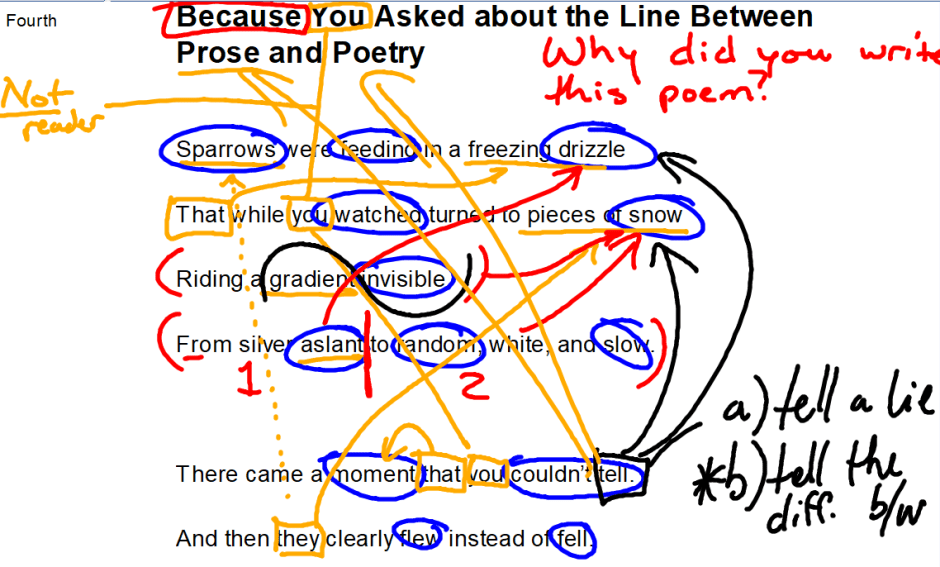

Because You Asked about the Line Between Prose and Poetry

Sparrows were feeding in a freezing drizzle

That while you watched turned to pieces of snow

Riding a gradient invisible

From silver aslant to random, white, and slow.There came a moment that you couldn’t tell.

And then they clearly flew instead of fell.

It’s a perfect start-of-the-poetry-unit poem because it has so much in it that makes poetry great. There’s enough ambiguity to necessitate a little digging. There’s a title doing all the work a good poem title should do — integral to the poem yet still standing a little aloof. There’s parallelism and patterns. There’s such an economy of language.

We work through it slowly. First, we find some of the ambiguities: who is the “you”? It’s not the reader. What is that “they” in the final line? They flew, so we think at first it might be the sparrows, but they also seem to have fallen at some point — birds don’t usually fall. “It’s the snow!” someone realizes.

We tackle the ambiguity of the word “tell.” “It’s not ‘tell’ like ‘to tell a lie’, is it?” I ask. We determine that “discern” might be a synonym. Or just “tell the difference between.” “Between what?” I probe a little further. They realize that it’s telling the difference between snow and rain, and that that is what’s going on in that final stanza: whoever is watching the birds is experiencing a moment when the rain is turning to snow and more specifically, experiencing that liminal moment when we can’t quite tell what it is.

We work on the title a bit. “It begins with ‘Because,'” I point out. “What does that signify?” They soon realize that before that must have been a “Why” question. “So talk to your seat partner — what is the understood question?” Eventually, we get it: “Why did you write this poem and give it to me?” Finally, we unpack the whole title: at some point, someone asked the poet, “What is the line between prose and poetry?” He left the question unanswered and returned at some point with a poem, which he gave to the interrogator. Confused, she asks, “Why did you give me this?” And the class says in unison: “Because you asked about the line between prose and poetry!”

“So he gives her a poem about birds and rain and snow?!?” I ask. “What kind of crazy answer is that?” They talk a little. I give them a hint: “Look for patterns. Look for repetitions.” Then they see it. Two things in the poem: rain and snow; two things in the title: prose and poetry. It’s time to put the bow on it.

I write on the board.

__________ : rain :: __________ : snow

“Let’s finish the syllogism,” I invite, and together they say, “Prose is to rain as poetry is to snow.” Or we could have done it differently: “Rain is to snow as prose is to poetry.” We get the same results. Snow and rain are made of water; poetry and prose are made of words.

“So what’s the poem’s answer to the question? What’s the line between prose and poetry?”

“Not much.”

Not much, indeed, and yet so much. So much difference and so many glowing faces as the poem that just a while ago made no sense to them at all suddenly is this beautiful and pithy exploration of the nature of written language.