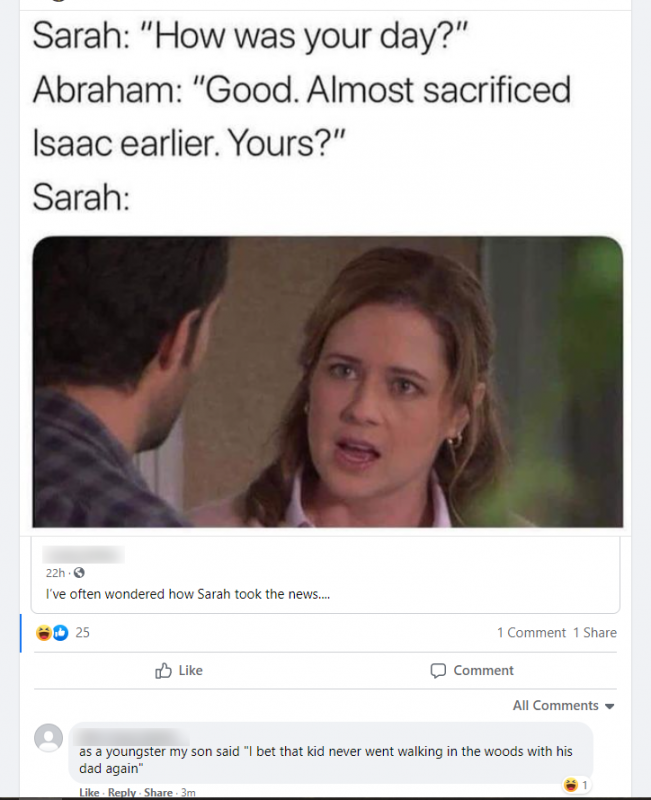

I knew taking the picture might break the spell: an at-risk student who, of her own accord without any prompting or suggestion, chose to read a book during free time after lunch might not be thrilled about having her picture taken. But on the other hand, it’s a picture of success, and when it’s a kid you’ve already grown to love in a way, a kid you’re already pulling your hair out over and cheering on and fussing at with a smile — you go ahead and take that chance.

Sure enough — “Mr. S! Don’t!” And the spell was broken. But unlike many magical moments, this one has evidence to back it.

I was drawn to this book for one reason: I grew up in the same cult as Walker, Herbert W. Armstrong’s Worldwide Church of God (WCG). Hence, as I read the book, I felt an eerie similarity with many of Walker’s experiences. His sense of otherness while at school was the same as my sense of otherness. His sense of impending doom while looking at peers in school was my sense of impending doom.

I was drawn to this book for one reason: I grew up in the same cult as Walker, Herbert W. Armstrong’s Worldwide Church of God (WCG). Hence, as I read the book, I felt an eerie similarity with many of Walker’s experiences. His sense of otherness while at school was the same as my sense of otherness. His sense of impending doom while looking at peers in school was my sense of impending doom.

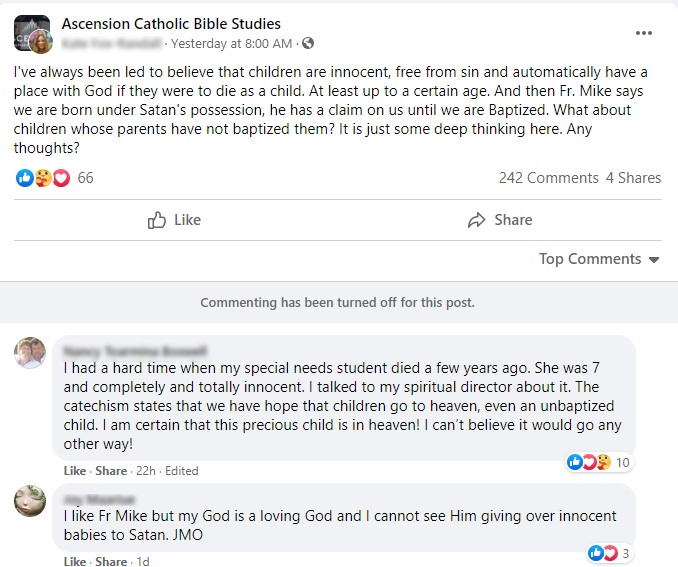

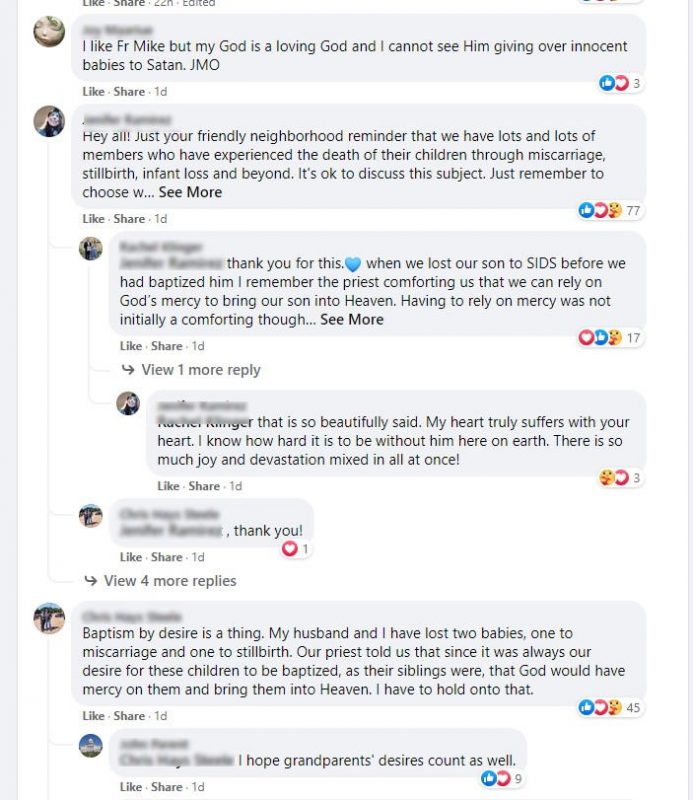

We see what we want to see. Social media offers the best example of that in the contemporary world, but sometimes, it’s not just evident in a macro-view but in individual postings.

We see what we want to see. Social media offers the best example of that in the contemporary world, but sometimes, it’s not just evident in a macro-view but in individual postings.