I was at the store and decided L needed something a little not-everyday, so I brought her some flowers.

Later in the evening, I realized she’d put some in a vase for Papa.

I was at the store and decided L needed something a little not-everyday, so I brought her some flowers.

Later in the evening, I realized she’d put some in a vase for Papa.

A few pictures from K’s day trip to Wraclaw. Why would she take a train there in the morning and a return train in the afternoon?

It’s a “remember where you are” moment. When my American friend and I encountered inexplicable bureaucracy while living in Poland, we always said to ourselves, “Remember where you are.” When things were unnecessarily complicated, we always said to ourselves, “Remember where you are.” When you had to get a stamp on this piece of paper to get a stamp on that piece of paper to get a signature and stamp on that application to get a piece of paper glued into your passport saying you could stay in Poland, we always said to ourselves, “Remember where you are.”

In short, there’s nothing like inexplicable Polish bureaucracy.

The pastor of K’s parish tweeted a link to “Has quantum physics smashed the Enlightenment deception?” by John Moran with the comment, “Reality is Rubbery.” I clicked through thinking, “Great — another ‘God of the Gaps’ article,” but hoping that I might be wrong. I wasn’t.

The article begins,

Forget Richard Dawkins, Stephen Hawking, Steven Pinker and the other high-profile God-denying “clever” boys. It is time for the broader implications of the 20th-century physics revolution, often described as quantum mechanics, to again be debated seriously and out in the “town square,” not just the backrooms of academia or in “deferring to the expert” interviews and documentaries.

The critical word there is “implications.” I’m not sure what Moran is suggesting here. At its heart, it’s simple: “Quantum mechanics is so weirdly different from the physics of our everyday reality that there must be implications for the nature of our everyday reality.” But must there be? There must be if we’ve already nurtured for millennia a belief in the supernatural, but all “quantum mechanics is weird” implies is “quantum mechanics is weird.”

Whatever these implications are in Moran’s mind, though, should be “debated seriously and out in the ‘town square,’ not just the backrooms of academia or in ‘deferring to the expert’ interviews and documentaries.” Part of the reason we “defer to experts” is because they are just that: they’ve forgotten more about their specialization than we laypeople even begin to understand. So when the people who actually work in quantum mechanics say, “No sorry — your implications that you want to discuss are based on misunderstandings of the quantum world,” as they do, we can just dismiss them. Who wants to defer to experts? After all, we’re seeing the benefits of not deferring to experts in the way covid is ravaging the conservative Christian anti-vaxers.

What does Moran say these implications are, though? To introduce them, he begins with a quote from a video by Leonard Susskind

It is hard to understand. Our neural wiring was not built for quantum mechanics. It was not built for higher dimensions. It was not built for thinking about curved space-time. It was built for classical physics. It was built for rocks and stones and all the ordinary objects and it was built for three-dimensional space. And that’s not quite good enough for us to be able to visualize and internalize the ideas of quantum mechanics and general relativity and so forth. …that can be extremely frustrating when trying to explain to the outside world. The outside world, by and large, has not had that experience of going through the rewiring process of converting their minds into something that can deal with five dimensions, 10 dimensions, or the quantum mechanical uncertainty principle or whatever it happens to be. And so the best we can do is to use analogies, metaphors.

Moran jumps on this:

Metaphor? So quantum physics has brought science full circle, back to the world of religion and the story telling methods of Jesus Christ and other religious figures.

Where quantum physics challenges everything, including those who arrogantly dismiss things like spirituality, is that it basically tells us two things:

- There might not be such a thing as an objective material object; and

- Consciousness has to be fundamental.

Now, let’s be clear. This new science does not prove the existence of God or anything else of that nature. But, it does shatter the arrogant certainty of those who think science is all you need and has killed off the spiritual. Through quantum physics we were again reminded of just how much we don’t know, especially about the mystery of the universe and the atomic world. In fact, we were not even close. This new quantum world was nothing like what scientists had envisaged prior to its discovery.

Why Moran gets so excited about Susskind using the word “metaphor” is confusing: does he not think that we use metaphor for anything other than religious ideas? After all, when we’re examining the quantum world, we’re looking at something so different from what we’re used to that we have to ground it in something we are used to — that’s what metaphor does. The use of metaphors does not equate scientists with theologians. This is an important distinction because scientists study the thing they study; theologians, unable to study gods directly, only study what other theologians have said. Scientists base their ideas on evidence; theologians’ try to do that, but their only evidence is ancient and anonymous manuscripts — again, studying what others have said about gods rather than studying the gods themselves. If, of course, we could study the gods themselves, there would be fewer atheists. Theologians would reply, “If we could study God, he wouldn’t be God,” but for one thing, that doesn’t necessarily follow. It’s based on the presupposition that gods must be so far beyond us that we can’t interact on their plane of existence. That very conveniently explains why there is no evidence for gods. For another, any god worth its salt could easily manifest itself regularly for study and confirmation of its existence. I do that with my own children daily; it’s too bad gods don’t do that with their children.

From there, Moran goes into a layman’s analysis of quantum theory brought about by this quote from Andrew Klavan’s article “Can We Believe?” subtitled “A personal reflection on why we shouldn’t abandon the faith that has nourished Western civilization.”

And is science still moving away from that Christian outlook, or has its trajectory begun to change? It may have once seemed reasonable to assume that the clockwork world uncovered by Isaac Newton would inexorably lead us to atheism, but those clockwork certainties have themselves dissolved as science advanced. Quantum physics has raised mind-boggling questions about the role of consciousness in the creation of reality. And the virtual impossibility of an accidental universe precisely fine-tuned to the maintenance of life has scientists scrambling for “reasonable” explanations.

Like Pinker, some try to explain these mysteries away. For example, they’ve concocted a wholly unprovable theory that we are in a multiverse. There are infinite universes, they say, and this one just happens to be the one that acts as if it were spoken into being by a gigantic invisible Jew! Others bruit about the idea that we live in a computer simulation—a tacit admission of faith, though it may be faith in a god who looks like the nerd you beat up in high school.

In any case, scientists used to accuse religious people of inventing a “God of the Gaps”—that is, using religion to explain away what science had not yet uncovered. But multiverses and simulations seem very much like a Science of the Gaps, jerry-rigged nothings designed to circumvent the simplest explanation for the reality we know.

The problem with Klavan’s thinking here is simple: he doesn’t realize that these conjectures are just that. No one is making dogmatic proclamations about multiverses or computer simulations. Why? Because there is no evidence or at least not enough evidence. Science is free to do what religion can never do: reject ideas it itself has created when evidence to the contrary appears. Indeed that is what science is all about.

It might seem ironic, though, that Klavan himself brings up the “God of the Gaps” fallacy in this article that amounts, in short, to the latest installment in the “God of the Gaps” theory since his whole idea here is nothing more than that. “Quantum theory is spooky and weird, and it’s outside our understanding now: therefore, God.” But irony is when the unexpected happens, and I’ve come to expect “God of the Gaps” theorizing in any apologetic piece, so far from being ironic, it is instead expected.

It is the Enlightenment Narrative that creates this worship of reason, not reason itself. In fact, most of the scientific arguments against the existence of God are circular and self-proving. They pit advanced scientific thinkers against simple, literalist religious believers. They dismiss error and mischief committed in the name of science—the Holocaust, atom bombs, climate change—but amberize error and mischief committed in the name of faith—“the Crusades, the Inquisition, witch hunts, the European wars of religion,” as Pinker has it.

By assuming that the spiritual realm is a fantasy, they irrationally dismiss our experience of it. Our brains perceive the smell of coffee, yet no one argues that coffee isn’t real. But when the same brain perceives the immaterial—morality, the self, or God—it is presumed to be spinning fantasies. Coming from those who worship reason, this is lousy reasoning.

There are just so many issues with this line of thinking here that I don’t even know where to start: with the false equivocation, with the question-begging, or with the general lack of experience this short passage exhibits.

To begin with, equating “the Holocaust, atom bombs, [and] climate change” is a curious mix. Certainly, some Nazis promoted pseudo-scientific reasoning for their antisemitism, but a far amount of it was good old-fashioned Christian antisemitism: the Jews reject the Christ, and so that is at the heart of their malevolence. The atom bomb is an unquestionably evil application of science so I’ll give him that. Climate change, though? I’m not even sure what he’s suggesting here. Is he saying that climate change was brought about by science? Well, it certainly was enabled by it, but our voracious appetites for convenience that science facilitated seem more responsible for climate change than the science itself. On the other hand, is he suggesting that climate change is a hoax that science is perpetuating on the world? That would seem more in line with the article’s source, City Journal, which is an unabashedly right/nearly-hard-right publication.

Klavan then equates, for all intents and purposes, the smell of coffee with God. “Our brains perceive the smell of coffee, yet no one argues that coffee isn’t real,” he writes, and I just scratch my head on that one. When my brain perceives the smell of coffee, I assume that there is coffee somewhere around because in my own experience, that odor has always been associated with coffee. However, if it’s terribly important to me to prove that there’s coffee, I can search for it. I can find evidence that the smell I’m encountering is indeed coming from coffee. It’s worth noting, however, that just because my brain perceives the smell of coffee there is coffee somewhere. I want to scream at Klavan, “Good grief, man, have you never encountered Scratch-And-Sniff stickers?!” We can fool our brain into thinking there’s coffee when in fact it’s not there. That’s why we investigate and examine and confirm. The smell of coffee is a bad example, though: we do this all the time when we think we smell something burning.

Klavan then equates smelling coffee with perceiving “the immaterial” such as “morality, the self, of God” in a perfect example of question-begging. No one suggests that people who say they are perceiving “the immaterial” are not having some sort of cognitive experience. Instead, skeptics are simply pointing out that what we think might be an experience of God isn’t necessarily that. We can fool people into thinking they smell coffee; atheists simply suggest that the mind is fooling itself into thinking it’s experiencing God.

It’s important to point out here that attaching the label “God” to any such experience depends on prior exposure to the idea that a god exists. If no one believed in a god, would we deduce it exists simply from these experiences? Scientifically illiterate people might; scientifically literate people probably wouldn’t. So this is a strange kind of cultural question-begging: the idea of a god was already in place; these experiences simply provide another hook on which to hang it.

Klavan concludes his article thusly:

Pinker credits Kant with naming the Enlightenment Age, but ironically, it is Kant who provided a plausible foundation for the faith that he believed was the only guarantor of morality. His Critique of Pure Reason proposed an update of Plato’s form theory, suggesting that the phenomenal world we see and understand is but the emanation of a noumenal world of things-as-they-are, an immaterial plane we cannot fully know.

In this scenario, we can think of all material being as a sort of language that imperfectly expresses an idea. Every aspect of language is physical: the brain sparks, the tongue speaks, the air is stirred, the ear hears. But the idea expressed by that language has no physical existence whatsoever. It simply is. And whether the idea is “two plus two equal four” or “I love you” or “slavery is wrong,” it is true or false, regardless of whether we perceive the truth or falsehood of it.

This, as I see it, is the very essence of Christianity. It is the religion of the Word. For Christians, the model, of course, is Jesus, the perfect Word that is the thing itself. But each of us is made in that image, continually expressing in flesh some aspect of the maker’s mind. This is why Jesus speaks in parables—not just to communicate their meaning but also to assert the validity of their mechanism. In the act of understanding a parable, we are forced to acknowledge that physical interactions—the welcoming home of a prodigal son, say—speak to us about immaterial things like love and forgiveness.

To acknowledge that our lives are parables for spiritual truths may entail a belief in the extraordinary, but it is how we all live, whether we confess that belief or not. We all know that the words “two plus two” express the human version of a truth both immaterial and universal. We likewise know that we are not just flesh-bags of chemicals but that our bodies imperfectly express the idea of ourselves. We know that whether we strangle a child or give a beggar bread, we take physical actions that convey moral meaning. We know that this morality does not change when we don’t perceive it. In ancient civilizations, where everyone, including slaves, considered slavery moral, it was immoral still. They simply hadn’t discovered that truth yet, just as they hadn’t figured out how to make an automobile, though all the materials and principles were there.

To begin with, the suggestion that an idea doesn’t have a physical correspondence only works with abstract things like morality and love. Two plus two equal four is simple: take two items; set two more beside them; count them. There. I don’t even know what Klavan is suggesting using that idea. “I love you” is harder to prove physically: we can’t scan brains and say, “Look — see that? That’s love.” Yet. All evidence points to the fact that our consciousness is bound in our brain, so it’s not unreasonable to think that we will indeed be able to do something similar in the future. It’s more “God of the Gaps” in action. “Slavery is wrong” is tricky because morality is tricky. Yet morality is very fluid at the same time. The Bible itself endorses slavery, and nowhere in scripture does Jesus or anyone else condemn the owning of other people. Indeed, it seems to suggest the opposite: in 1 Peter, we see an appalling command: “Slaves, in reverent fear of God submit yourselves to your masters, not only to those who are good and considerate, but also to those who are harsh” (1 Peter 2.18). The book of Philemon is almost as bad:

I am sending [Onesimus, your slave]—who is my very heart—back to you. I would have liked to keep him with me so that he could take your place in helping me while I am in chains for the gospel. But I did not want to do anything without your consent, so that any favor you do would not seem forced but would be voluntary. Perhaps the reason he was separated from you for a little while was that you might have him back forever—no longer as a slave, but better than a slave, as a dear brother. He is very dear to me but even dearer to you, both as a fellow man and as a brother in the Lord. (Philemon 12-16)

Here Paul could have said, “Slavery is wrong.” Here he could have said, “I am not sending him back because I have no authority to do so. He is a free human being with his own will.” But he sends him back and suggests that, since Onsemus is a Christian too, perhaps Philemon should treat him a little better.

Many proponents of slavery used the Bible to endorse the position so maybe this wasn’t the best moral to use in trying to suggest that morality implies a god.

From there, though, Klavan makes a hard, awkward turn to Christianity. He’s essentially saying, “Words often don’t have physical referents in the real world, and Christianity calls Jesus ‘the Word,’ so it’s likely true.” It’s a hard sell, completely out of the blue, completely illogical, for anyone other than a Christian who already accepts all this. Of course, given the fact that it’s a conservative source, Klavan is justified in assuming that most of the readers already accept these presuppositions, but the ideas themselves make very little sense without those presuppositions, which we skeptics reject. This, then, is still another example of question-begging.

The idea that Jesus spoke in parables in order to make the connection between language and ideas that have no physical referent is just speculation like scientists’ speculations about multiverses, so I’m not even going to deal with it.

Finally, there’s this: “In ancient civilizations, where everyone, including slaves, considered slavery moral, it was immoral still. They simply hadn’t discovered that truth yet, just as they hadn’t figured out how to make an automobile, though all the materials and principles were there.” Funny: if there was a god that felt that slavery is immoral and he wrote a book, it’s ironic that he didn’t say as much in that book but left it for us to discover while untold millions suffer in slavery.

Despite the fact that L had a less-than-positive experience with the line park just outside of Jablonka, it became just about her favorite activity when at Babcia’s.

Overcoming

This year the Boy is old enough to do the larger courses, and it’s clear: he’ll probably share L’s opinion of the park.

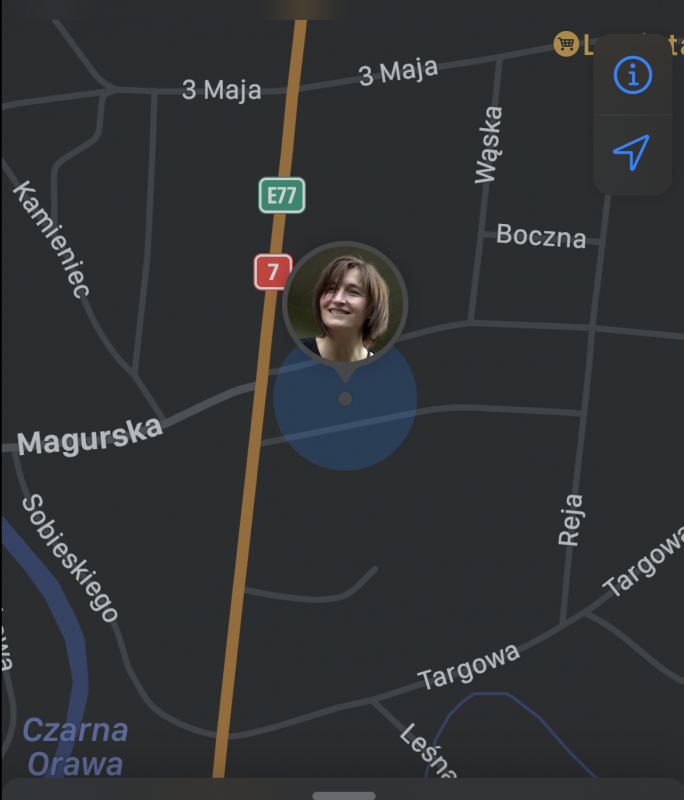

I check K’s location in the morning, knowing what I’ll find. If there had been any issues, K would have contacted me. But there she is, safe in sound in Jablonka.

In the afternoon, we FaceTime a little while as K and E return from a walk to the river — the walk. I see immediately the changes: at least half a dozen new houses along the gravel road where, ten years ago, there was only one and where, when we left Poland in 2005, there were none. Not terribly impressive growth by Greenville standards, to be sure, but in a little village…

As for other pictures — perhaps tomorrow. Today was a rest day, a day with Babcia — as it should be.

It’s been four years since we last did this. It’s actually been more like six — four years ago, we all went to Poland together. It was the 2015 trip that was split up. I wasn’t even planning on going that summer, in fact. This year, just K and E are going, and that long long journey began this morning with a departure from the house at 2:15 to arrive before 4:00 to make it for the 6:00 flight from Charlotte to JFK. We usually go Charlotte-Munich-Krakow, but with covid restrictions and such, K wanted to fly directly to Poland, which meant leaving from JFK. She reasoned she stood less of a chance of having problems getting into Poland with an American passport and an expired Polish passport than into an EU state. When we did all this planning, Americans were still not admitted into Europe, I think. So we left ridiculously early to arrive the requisite 2 hours before departure.

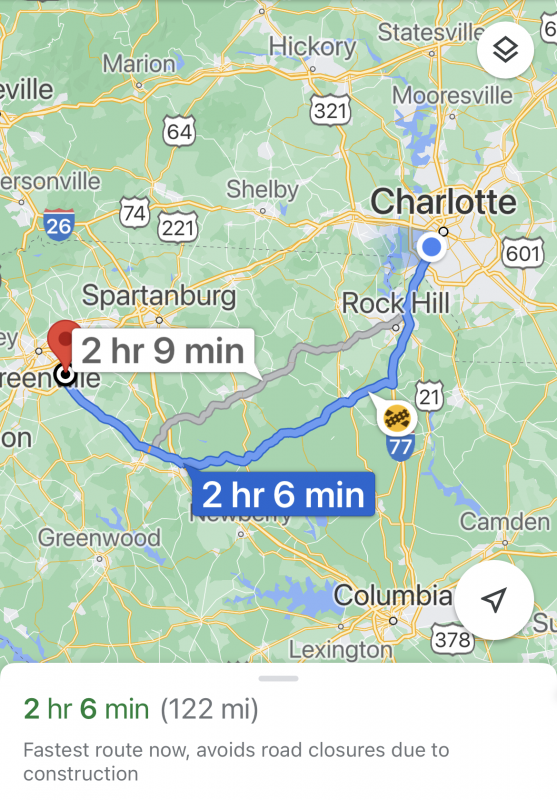

You can see in K’s expression just how excited she was. Even though the drive home would normally only be about an hour and twenty minutes, Google routed me a different way: 85 south was closed at some point for construction. We’d seen the backup forming (at 3:00 am), but I’d hoped it would have cleared up by the time I was heading back that way.

It was not, turning an hour-and-twenty-minute drive into a two-hour-twenty-minute drive. (I stopped just before getting on I77 to double-check, hence the two-hour-six-minute time.)

I got home to find Papa awake and needing assistance. By the time everything was squared away, it was 6:35. I set the alarm for 7:35 so I could get up to take L to volleyball conditioning, but of course I never really went to sleep. I was just dozing off as the alarm sounded. Back home at 8:00, I started Papa’s morning routine, then left the rest to our wonderful CNA and headed out to the store to buy a few things. No point in lying down for an hour again, I figured.

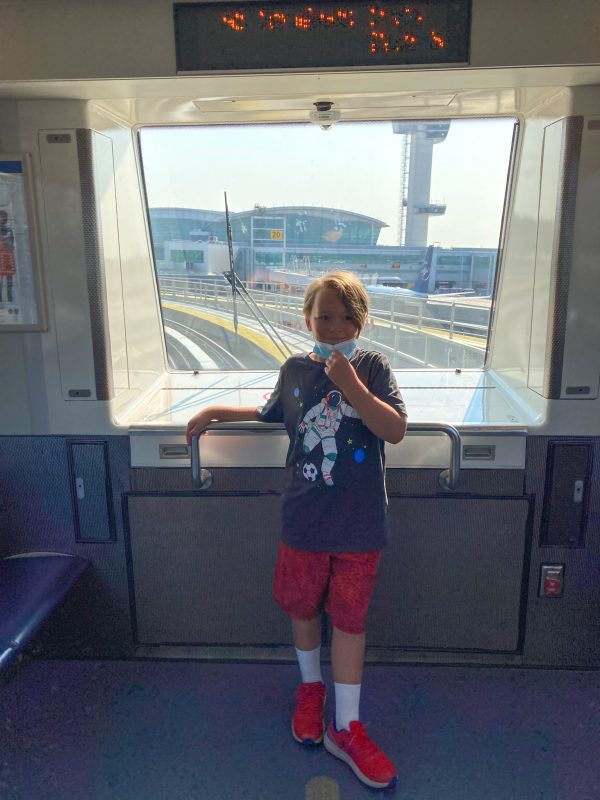

In the meantime, K and E were having their own adventure, collecting their bags (not checked all the way through because the original plan had been to drive to NYC), finding their way to the terminal from which LOT departs — all of which absolutely thrilled the Boy. In Munich the last time we were there, he was thrilled by all the moving walkways, all the planes visible from the terminal, and even the self-enclosed smoking pods. I’m sure it was just as thrilling in JFK.

“An airport is a paradise for a nine-year-old boy,” I texted K. I always loved going to the airport for Papa’s business trips: the hustle and bustle, the equipment, the planes.

But even then, a little one can get tired and frustrated when the layover is hours long. K had a secret weapon, though:

And of course, he knew what was waiting for him on the plane — he’d been talking about it for the last two weeks:

The final text from K: we’re on board but take-off is delayed thirty minutes. For once, that’s not a problem: there’s no connection to worry about. Waiting at the other end of the flight will be her brother, ready to bundle them off to Babcia’s place.

I can only imagine Babcia’s excitement after four years.

The Girl finished her summer volleyball season tonight by winning the grass championship for her age group. Her partner was a young lady she met while playing club ball this summer and with whom she immediately bonded. Birds of a feather and all that.

She was also my student last year, which made for some amusing situations.

“What are you doing, M?” I might ask when the team was taking a break between games.

“Studying for your test, Mr. Scott.”

The Boy likes to help, so much so that it sometimes can get in the way. But often it is really sweet how he pitches in. Tonight, for example, he insisted on getting Papa’s evening water prepared, thickened with some magical mystery white powder that turns water into a pudding-like goop that’s easier for Papa to swallow and less risky as well. In the meantime, K was preparping Papa’s dinner: warm blueberry cobbler and ice cream. Soft, easy to chew, tasty — a perfect dinner.

E then excitedly asked if he could help Papa eat.

“Of course,” we said. “Just make sure you go slowly: it’s difficult for him to swallow at times.” And so he stood patiently by Papa’s bed and helped him eat.

Nothing brings Papa back more completely than his grandchildren. Sometimes, when I walk in and greet him, I get no response. He’s off somewhere, seeing something, hearing something — but not there. Then E can walk in right behind me and say, “Hey, Papa,” and he perks right up: “Hey, little buddy.”

Once Papa is ready for his night’s sleep, I headed out to walk the dog while the Boy and K played cards. Last night, it was chess with me.

And L? She’s fourteen — just a little too cool to spend too much time with the family. Plus, she was at work today: she needed some down time.

He takes a deep breath and then pauses. I watch his chest and wonder if this is it. I count — one, two, three. And his chest rises once again. It’s just like sitting with Bida two and a half years ago.

“Normal” is a fluid idea in our home these days with Papa’s condition, but with two kids in the house, we also have to try to keep the old “normal” part of our new normal.

Yesterday, for example, I took the Boy swimming in the afternoon (the Girl was not interested in going just to float around with a bum ankle if she didn’t have a friend with her, and it was too late to arrange all that), and afterward we went out for our favorite Boys’-Night-Out meal: Mexican. A taco and enchilada with beans and rice, all covered with sauces and queso?! Who wouldn’t love that?

“The only problem with going out for Mexican,” the Boy explained, “is that it’s so easy to stuff yourself.” That’s certainly true.

In the afternoon today, I spent a lot of time with the dog, kicking the ball for her to retrieve. Again and again and again.

She came back in a slobbering, exhausted mess.

Papa’s existence when the meds that keep him calm and sedated changes from moment to moment: There are lucid moments when he is just like the Papa we all know and love, there are moments enveloped in hallucinations, and there are moments that seem to fall somewhere in between.

This is a lucid moment.

He occasionally smiles while hallucinating, and it’s such a mischievous little smile that I want to catch a photo of it. Tonight, he smiled that smile, a little kid’s smile when he’s gotten away with something and yet is still just nervous enough to realize that he might not have in fact gotten away with it. An “I know you know I did it, but please don’t tell on me” smile. I didn’t have a camera ready, though, so I went downstairs and got our good Nikon. I was telling Papa about that smile and how much I wanted to get a picture of that smile, so he smiled for me. It’s not the smile I’d initially wanted, but it was a smile of intent, a smile of purpose, a smile to fulfill a request. A smile that said, “I know I’m having a lot of problems following instructions when you ask me to open my mouth or to roll over. Right now, though, I can do exactly what you asked me to even if I’m not sure why you want me to. I trust you and will do it because I trust you.”

Those lucid moments are rare, and they are increasingly rare with each passing day. The hospice nurses all say that they have never seen anyone with Parkinson’s progress this quickly. Every day is literally a new normal. Yesterday it became clear that he could no longer eat solid food because he didn’t chew it. He kept it in his mouth sometimes, partially chewed it others, and every now and then chewed and swallowed, each motion of his jaw a supreme effort. Today we gave him only pureed food, and in the morning he did a good job with it, but in the evening, it was difficult to get him to open his mouth to eat. He no longer can draw liquid through a straw, and when he does get liquid in his mouth, he almost chokes on it, so we bought thickener and we spoon-feed him his thickened water to keep him hydrated. Today we also stopped giving him pills to swallow: they’re all ground up own, sprinkled on spoons of yogurt. What tomorrow will bring is a complete mystery.

This is a hallucination.

He pulls threads out of thin air. He talks to people who over his bed, who sneak behind his bed and hide, who stand on either side of his bed. Strangers come to visit him as well as friends. Nana comes often. “Hey, babe! Don’t you think it’s about time we get out of here?”

This is the picture I hesitate to put on here, but this is the reality he’s suffering now. This is the reality that leaves us shaking our heads wondering how much one poor man has to suffer. This is the reality that creates new habits: I walked out of the room today just as he started saying something. I paused for a moment, then realized he was talking to a hallucination. I didn’t respond. I just continued out.

These are the moments when he seems most vulnerable, too. The hallucinations don’t frighten him: he once said he saw a hangman standing by his bed with a noose, but other than that, the people who come to visit him seem relatively harmless. He’s restless, though: he’s always been a mannerly man, a gentleman, a problem solver, so he wants to respond to all the things he sees around him, deal with all the issues around him (the threads that hang endlessly over his bed, for instance). In the past (i.e., earlier this week), when he started talking to these hallucinations or pulling at the threads, we did as the nurses advised: we played along and asked the person he was talking to to leave or took that threads ourselves. “Don’t worry,” we’d then reassure him. “We asked him to leave. Did you hear? Did you see him leave? He just walked out the door.” Now, he doesn’t engage with us when we say those things. That change has come in the last 36 hours.

This is a mystery.

Not hallucinating, not engaging with us — just there. Remembering? We don’t know. This might disappear tomorrow because it only appeared a few days ago. The way things change, “normal” is a fluid concept that can change within one day.

This is the only thing that seems to help these days.

This is what I feel guilty about neglecting with Nana: I didn’t realize how little time we had left with her once she came back from rehab. I didn’t realize how quickly she could go. I didn’t take the time simply to sit with her and to talk to her as much as I could have or should have. And now, so much that we say to Papa just goes unacknowledged. Perhaps because he didn’t hear. Perhaps because he didn’t understand. Perhaps because he was busy talking to someone else. But there’s one thing he understands.

A gigantic home on a long, narrow lot…

“Only in Poland” my friend and I would laugh.

Night can be the most trying time with a Parkinson’s patient since the disease can throw all kinds of obstacles in the way of a simple night’s sleep. Of course, there are the hallucinations that plague one night and day without proper medication, and as the disease progresses, the dosage of that medicine needs to be constantly adjusted. With Papa and his lightning-fast deterioration, what was an adequate dose three or even two days ago no longer has the desired effect. So Papa can spend a lot of the night talking to his hallucinatory friends, reaching for hallucinated objects, and puzzling over imagined problems. It’s hard to go to sleep like that.

Parkinson’s also affects sleep: one of the 10 early symptoms of Parkinson’s is trouble sleeping.

And so some nights at eleven, when everyone should be in bed, Papa has been lying in bed for three hours yet he’s still talking to people who are not there, reaching for things not there, looking around the room at sights only in his mind, and in worst-case scenarios, trying to get out of bed — something that would be disastrous.

The frustration we all feel about this is ineffable.

When Papa was in his late thirties or early forties (I can’t really remember), we had a family membership at the local YMCA, and he liked to play basketball. He didn’t like playing with men his age — too slow. He played with the twenty- and twenty-one-year-olds. It was hard and aggressive, and while I can’t really remember how good Papa was at basketball, I do remember how tenacious he was, how he never gave up.

One time he was breaking for the basket, forcing his way through a couple of defenders, when he leaped, shot, landed on his ankle at an angle, and fell in agony with a snap that everyone heard.

As Papa lay there on the floor, rolling about in agony, one of the other players leaned into the group huddled about him and said, “If it’s any consolation to you, sir, you made the basket.”

Tonight, L made a block that won the point but resulted in an ankle injury. A young lady on her team told her, “But L, you won the point.”