As an English teacher, there are times that demand I drop what we’re doing in class and talk about what’s going on. Or as Kelly Gallagher put it,

Sometimes when history unfolds, it immediately supersedes tomorrow’s lesson plan. Today is one of those days. Students will need to read, write, and talk about this.

I took his thoughts (and one of his ideas) to heart and took the opportunity to do a short media studies lesson. We looked at seven screenshots of seven media outlets and asked a few questions about them:

- What is said?

- What is not said?

- How is it said?

- What images were selected?

- What images were not selected?

- Why this order of links?

- Why the selected font sizes?

- Who is the intended audience?

- What is the intended purpose?

- What inferences can we draw about the source?

As best I could, I scrubbed all indications of the source from the screenshot. I missed a bit from the CNN shot, observant students probably noticed the “South Carolina Public Radio” media player on the NPR shot, and I accidentally left in image attribution for The Washington Times but otherwise, I kept them a mystery. (The first time I went through the lesson, I told the students which images came from which sources. Because of the reaction, I decided not to do that in subsequent lessons.)

Here are a few things the students noted.

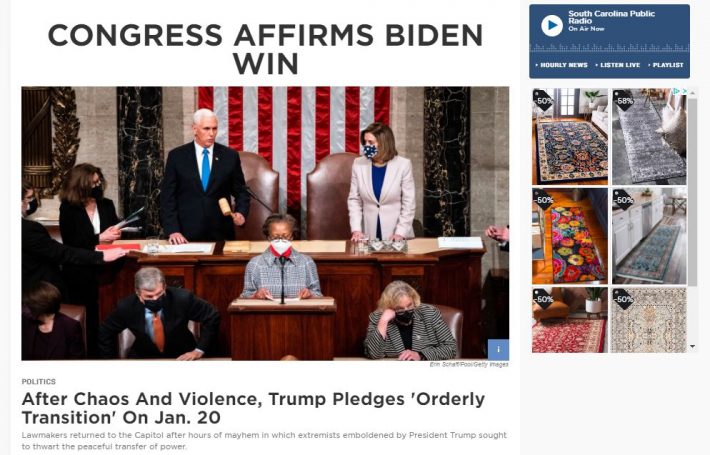

Screenshot 1: NPR

Of the two big stories from January 6, this source focused on the positive (for the survival of our democracy, that is) story. The attack on the capital was referred to only as “chaos and violence.”

Screenshot 2: The Washington Times

Students, after I explained who Newt Gingrich is and what “GOP” refers to, decided this was definitely targeting a right-leaning audience. I was surprised that not a single student knew what GOP meant.

“Why did Republicans get that nickname?” they all asked.

“I don’t know.”

“Do Democrats have an equivalent nickname?”

“Not that I know of.”

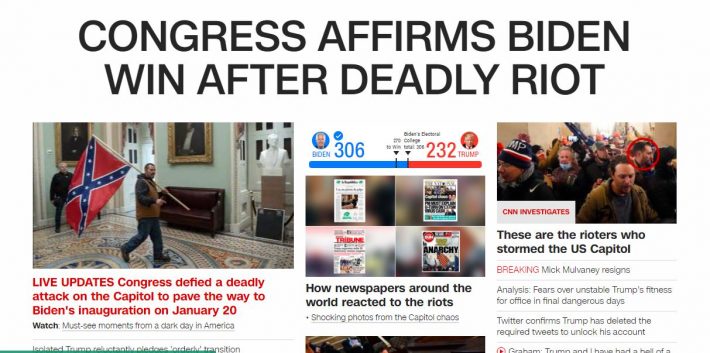

Screenshot 3: CNN

Students immediately commented on the amount of screen real estate the headline takes up. They also commented on the vote count graphic.

“I’ve only ever seen this on election day,” I pointed out.

We discussed the use of the term “rioter.”

“What else could we call the people who participated in that event?” I probed.

They came up with a list:

- protesters

- gang

- terrorists

- attackers

- mob

I added one more: insurrectionists.

We put the words on a continuum, and they decided that the most benevolent was “protesters.”

“Using that term would suggest they support them,” one student succinctly observed.

At the far end: insurrectionists. All that being said, they felt that “rioters” was the most objective.

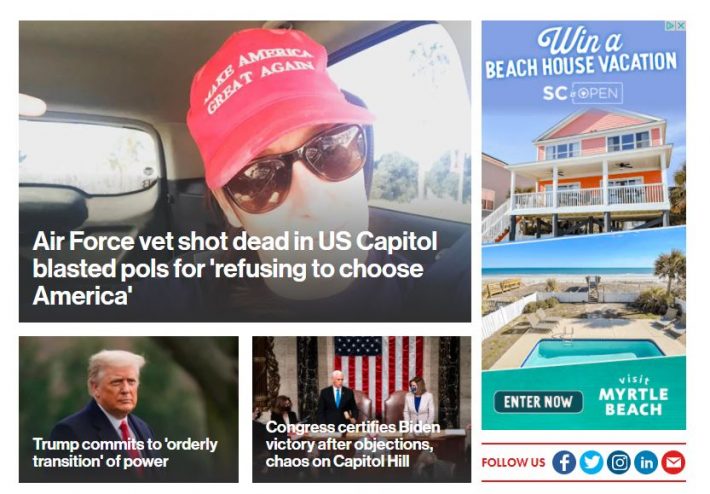

Screenshot 4: The New York Post

Students immediately noticed that, with source 4, we could win a beach house vacation! In other words, they realized quickly that this site relies heavily on ad revenue.

“Maybe it’s a blog,” someone ventured.

As to the content, they thought it was striking that the lead story was about the rioter who was shot, but they also thought it was significant that the headline left so much out.

“In the Capitol — it sounds like something happened to a tourist or something.”

Screenshot 5: The New York Times

This source included a video, which suggests that the images in the other articles are screen grabs from this video.

There’s also the word choice: mob and mayhem.

“What’s ‘incited, Mr. Scott?” they asked. “Isn’t it like ‘encouraged’?”

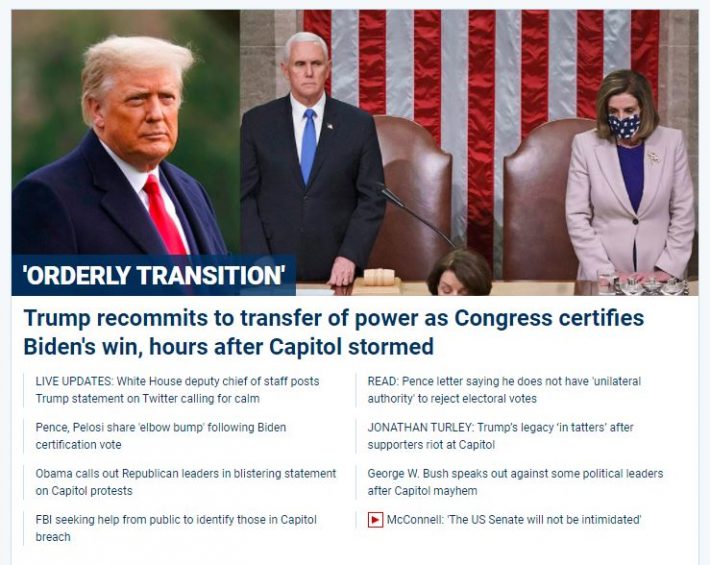

Screenshot 6: Fox News

The immediate thing students noticed was “Orderly Transition” is the headline. It’s in all-caps, so it somewhat dominates the second headline below it.

Also, in the picture, Pelosi looks a little weak: she’s a little slouched over with downcast eyes. If this was from a video, it could have been a conscious choice, which would indicate a bias. Additionally, with the placement of Trump’s picture, it seems to highlight the distance between the two parties.

Screenshot 7: The Washington Post

The final shot came from The Washington Post. It seemed, the kids noted, to balance between both: the headline was about Biden; the image was from the assault.

“If you look at the area just below it,” I pointed out, “you’ll see what looks like the tops of letters. That was the headline for the second story, which was about the assault.”

Once we were all through, I reminded kids that the purpose of the lesson was not to teach them what to think but rather how to think. “An informed citizenry is critical to the success of any democracy,” I said.

Oh, the things we (rightly) leave unsaid in the classroom when talking about such matters, though…