Friday Fire

Thursday at Home

We stayed home today because of potential high winds due to the remnants of Zeta. Since we’re all so used to it, switching to online learning was a snap for everyone. K pointed out the now-obvious: they’ll be more willing to do this in the future with less risk because they know we can do elearning.

No more snow days. More wind/rain/inclement weather elearning days.

Unfortunately, the neighbor up the street with the trashy Halloween decorations suffered little damage to his display…

First Day at 100%

We go to school five days a week now, and this has advantages and disadvantages.

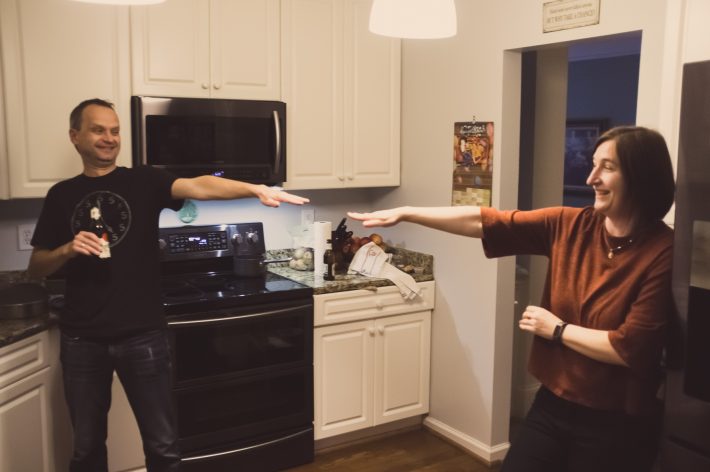

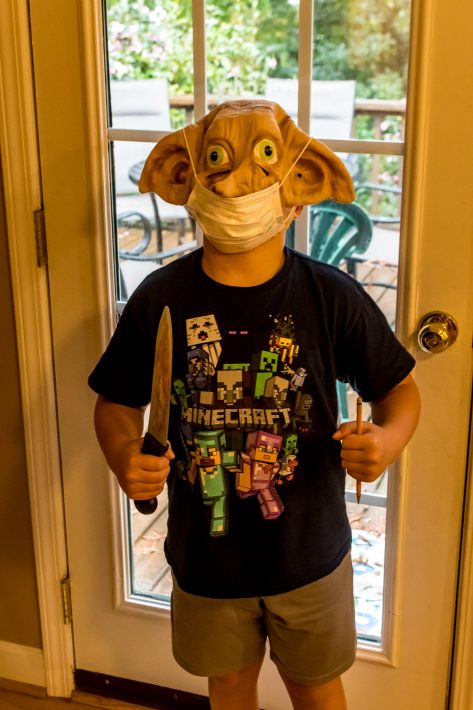

First, I get all my friends back. A and O are my two best friends, and because of Covid, I didn’t have them in class since we went to school in different groups. Today, though, we go five days a week, and we don’t have two groups anymore. We talked about the surprise I’m going to do for their mom. I’m going to take a Dobby mask and try to surprise her and maybe spook her a little bit with a fake knife.

Next, I feel better having a big group of twenty people. I think that everyone in one class should be together and not split up into two groups.

However, I have to wear a mask all day, and this is a disadvantage. A mask is uncomfortable because it rubs on your mouth, and it itches. Even though it’s uncomfortable, I have to do it because covid is bad, and we have to stop the spread. Masks help stop the spread.

I think that it’s very much better than two groups because I get so many people to be with.

Working from Home

Chicken Fingers

We’ve gotten into some lazy food habits, which means some unhealthy food habits. We’re in the process of turning them around.

One thing has to do with snacking. The Girl is often very hungry again later in the evening, even if she’s eaten a full dinner. Teens tend to be that way. She’s been eating a few chicken nuggets from Aldi as her evening snack a couple of times a week for some time now.

Today, she learned how to make her own chicken fingers from fresh chicken. Completely healthy? Probably not. Better than what she was eating? Definitely.

Removal

Sunday in the Fall

Tryouts

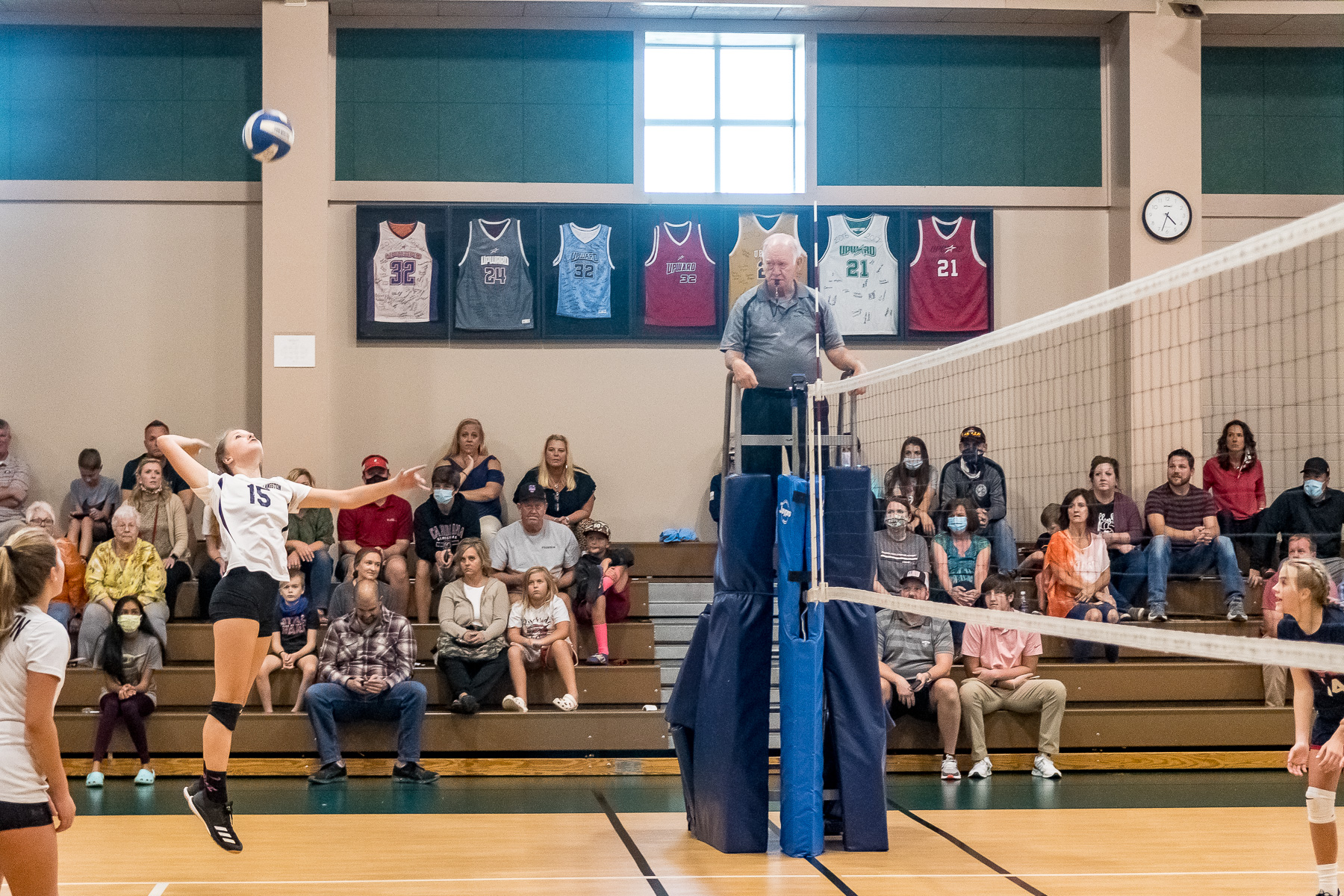

Today was the first of three days of tryouts for club teams. L will be trying out for two clubs: Excell Sports, where she played last year, and Carolina One, which gave her the cold shoulder last year.

Today was day one at Excell.

Her coach from last year was there. “L’s really improved,” he said.

The owner and head coach of Excell, Shane, talked to L and me after tryouts.

“Everyone was impressed with your hitting,” he said. “Last year, you were a baby giraffe: you had these long arms and legs and didn’t know what to do with them. You know what to do with them now.”

Remembering and Forgetting

Yesterday, we went over a new poem: Billy Collins’s “Forgetfulness.”

The name of the author is the first to go

followed obediently by the title, the plot,

the heartbreaking conclusion, the entire novel

which suddenly becomes one you have never read, never even heard of,as if, one by one, the memories you used to harbor

decided to retire to the southern hemisphere of the brain,

to a little fishing village where there are no phones.Long ago you kissed the names of the nine muses goodbye

and watched the quadratic equation pack its bag,

and even now as you memorize the order of the planets,something else is slipping away, a state flower perhaps,

the address of an uncle, the capital of Paraguay.Whatever it is you are struggling to remember,

it is not poised on the tip of your tongue

or even lurking in some obscure corner of your spleen.It has floated away down a dark mythological river

whose name begins with an L as far as you can recall

well on your own way to oblivion where you will join those

who have even forgotten how to swim and how to ride a bicycle.No wonder you rise in the middle of the night

to look up the date of a famous battle in a book on war.

No wonder the moon in the window seems to have drifted

out of a love poem that you used to know by heart.

Collins is famous for poems in which a witty, whimsical tone belies a deeper, subtler idea. He’s perfect for teaching kids what I call the two levels of poetry: what’s happening in the poem and what the poem is about. His work also often shows a clear tonal shift, and that’s something I want my students to be able to sense.

Yet eighth-grade students often miss the whimsy in his poems. They read something like this without cracking a smile. They even watch an animated version of it without reaction:

So we have to walk through it carefully.

This year, I started by focusing on the fifth stanza:

Whatever it is you are struggling to remember,

it is not poised on the tip of your tongue

or even lurking in some obscure corner of your spleen.

“Everyone has heard the phrase ‘it’s on the tip of your tongue,’ right?” I asked. Of course they had. But I had to lead them into “lurking in some obscure corner of your spleen.” We mapped it out:

- “poised” turns into “lurking”

- “tip” transmutes into “some obscure corner”

- “tongue” becomes “spleen”

“Have you ever heard anyone say some memory is ‘lurking in the corner of my spleen’?” I asked. And everyone laughed. “That’s what the poet was getting at!”

Once they got it, they saw the other instances of whimsy in the poem:

- We talked about the idea of “the memories you used to harbor” deciding to “retire to the southern hemisphere of the brain, / to a little fishing village where there are no phones.” “Look at all that absurd detail!”

- We visualized kissing “the names of the nine muses goodbye” — “I’m going to miss you so much! What will life be like without you!?”

- We imagined seeing “the quadratic equation pack its bag.” “It’s over, do you hear!? I saw you last week in the park with that pythagorean theorem!”

- We saw the drama build up with the line “It has floated away down a dark mythological river” only to fizzle out pathetically with “whose name begins with an L as far as you can recall.”

It’s not the first time students have struggled to see the humor in Collins’s poetry. When we do “The Lanyard” next week, the same thing will happen. I’ve come to the conclusion that it’s an age thing: that type of whimsy just goes right over their inexperienced heads.

Down at the Swings Again

Late October

Written a couple of years ago but still true

It’s late October. The first quarter is drawing to a close, and students sit wading through district-mandated benchmark tests. Despite this, its one of my favorite periods of the school year. The honeymoon period is over, and we’re up to our noses in work that occasionally seems like it might sweep over us all. The kids are getting comfortable with the demands of an honors course, and we’ve all settled in for several months of work. But more than that, more personal, when I look out over the class, the students are now not just faces to which I’m trying to attach names; when I scroll down the roll at the start of each class, the names are not just sitting there waiting for me to combine with a face.

They’ve emerged as this amalgamation of worry and laughter, of procrastination and focus, of silliness and maturity — everything that makes thirteen-year-olds and fourteen-year-olds thirteen-year-olds and fourteen-year-olds. They’re still kids but in bodies that are nearly fully developed, and the awkwardness that implies radiates from every smile of accomplishment and glistens from every tear of frustration that accompanies the eighth grade. Their brains, developing in new and unexpected ways, are awash in a warm flood of newly-released hormones. They realize they’re not adults yet but in some sense are convinced they are. They’ve become people that I think I might actually have quite warm feelings toward instead of just a list of names an administrator has handed me.

I look around the classroom and see faces behind which are entire universes of experiences, worries, excitements, concerns, joys, and doubts. Each face is a mixture of all these things and more.

I see B, who’s new to public school and worried the effect her shyness and lack of experience might have on making friends but who is, nonetheless, making friends because she is a genuinely good soul and everyone sees that. I glance over at J, sitting with his head down, a child I suspect is just on the edge of the autism spectrum, who seems just enough aware of his social awkwardness to be annoyed but not defeated by it. H sits in front of the class, a teacher’s dream in so many ways: quick, bright, kind, helpful, she would probably be accused of being a teacher’s pet if it weren’t so obvious that she does these things because it’s just the person she is. In the corner desk is D, who has a mouth that seems incapable of pausing at times yet is impossible not to like despite his frustrating behavior. In the middle of the room sits quiet J, who struggled mightily at the beginning of the year and wanted to leave the class but has in the last weeks blossomed into a determined but struggling writer who has shown more improvement in the last month than some students show all year because she is so very determined to make that improvement.

In short, it’s the time of year that I realize I was wrong in my assumptions at the end of the last year, just as I am wrong every year.

“I love these silly kids!” I think at the end of the year. “There’s no way any other group can compare to them.”

And then the next year’s students come, and over the course of a few weeks they go from being names on a list to kids I’m working with, laughing with, fighting with, crying with, and I see that the impossible has happened: once again, I have the greatest group of kids I could ever imagine working with, and I’m equally convinced that they are irreplaceable, that I can never feel for another group of kids what I feel for these kids.

Birds and Testing

The kids are all taking a benchmark test. We’re spending two hours of each of the two days students will be in school taking a district-mandated benchmark test, which, truth be told, will be of little to no value to me. I know where my students are; I know where we’re going; I know what I haven’t covered. Further, I know the students better than a benchmark could show

In the midst of all this, a bird flies up to the window and perches on the sill. It cocks its head as it investigates all the humanoid forms on the inside, all hunched over glowing boxes, almost all oblivious to the bird’s presence. Except Anna. She’s sitting next to the window and has watched the bird flutter up. She takes a break from her test and looks over at the bird, smiling and likely grateful for the break the bird’s presence has brought.

Birds come to this window regularly, but their presence injects a bit of tragic chaos into the class atmosphere. Twice this year, birds have flown into the window with a sickening thud, only to lie outside the window slowly dying of the blunt force trauma the window and physics delivered. They flap about just outside our window as if they are trying to distract a predator to lure it away from its nest. Those times, though, the bird was not faking.

There’s an analogy there, I think. The window is our education system: it can either offer a glimpse into a new world, inviting participation and fascination, or it can just break students, often with rigid testing systems and the one-size-fits-all mentality they can engender.

During this highly stressful year, I think testing is more the break-students type of experience than anything else. Why are we spending two hours of each of the two days this week testing? Our students are in the classroom two days a week. That’s about fourteen hours a week. And we’re four of those hours (about 28.5%) of that time administering benchmark tests? Benchmark tests?! I can tell you just have close my students are to any given benchmark without taking nearly thirty percent of my week’s time with students to do it.

On a positive note, though, the assistant principal came into my room about ten minutes into the lesson with the district’s assistant superintendent so he could see how I’m streaming my class. Apparently, I’m something of a trailblazer with this in the district. I, for one, can’t understand why more teachers aren’t doing it on their own: it returns my planning to normal, pre-covid dimensions. I no longer have to create something separate for the kids at home. I do, though, have a unique situation in that I teach only honors kids, which means that most of them are motivated to log on and follow along from home. Other students might not be so willing. (Still, said students — at risk, we would call them — are not necessarily doing the elearning anyway. What difference does it make which type of online learning they are neglecting? I’m fortunate that most of the kids follow along.

It’s Fine When We Do It

A lot of people are supporting Trump because, although they don’t think he’s an ideal candidate, they see him as better than the boogie-man-Stalinst-wannabe straw man they fear Biden is. In other words, they see it as a question of the survival of the republic: if Biden wins, he and far-left radicals will work to turn the US into a socialist/communist country, they fear. The United States will cease to be, they say.

Yet some take it a bit further:

Radical right-wing conspiracy theorist Rick Wiles declares that "if Joe Biden wins on Nov. 3, the American people cannot allow that man to be sworn in." pic.twitter.com/RHDasrPwpP

— Right Wing Watch (@RightWingWatch) October 19, 2020

Someone like Wiles would likely be willing to let Trump be president for life, and make it hereditary — get rid of elections, in other words — in order to protect the US against this perceived threat. In other words, to save the country, he would be willing to destroy the country. Shades of the Battle of Bến Tre.

This sort of worship of Trump is surprisingly common in the evangelical community.

For a group that calls itself Christians and swears never to put any god above their god, they certainly do that an awful lot with Trump.

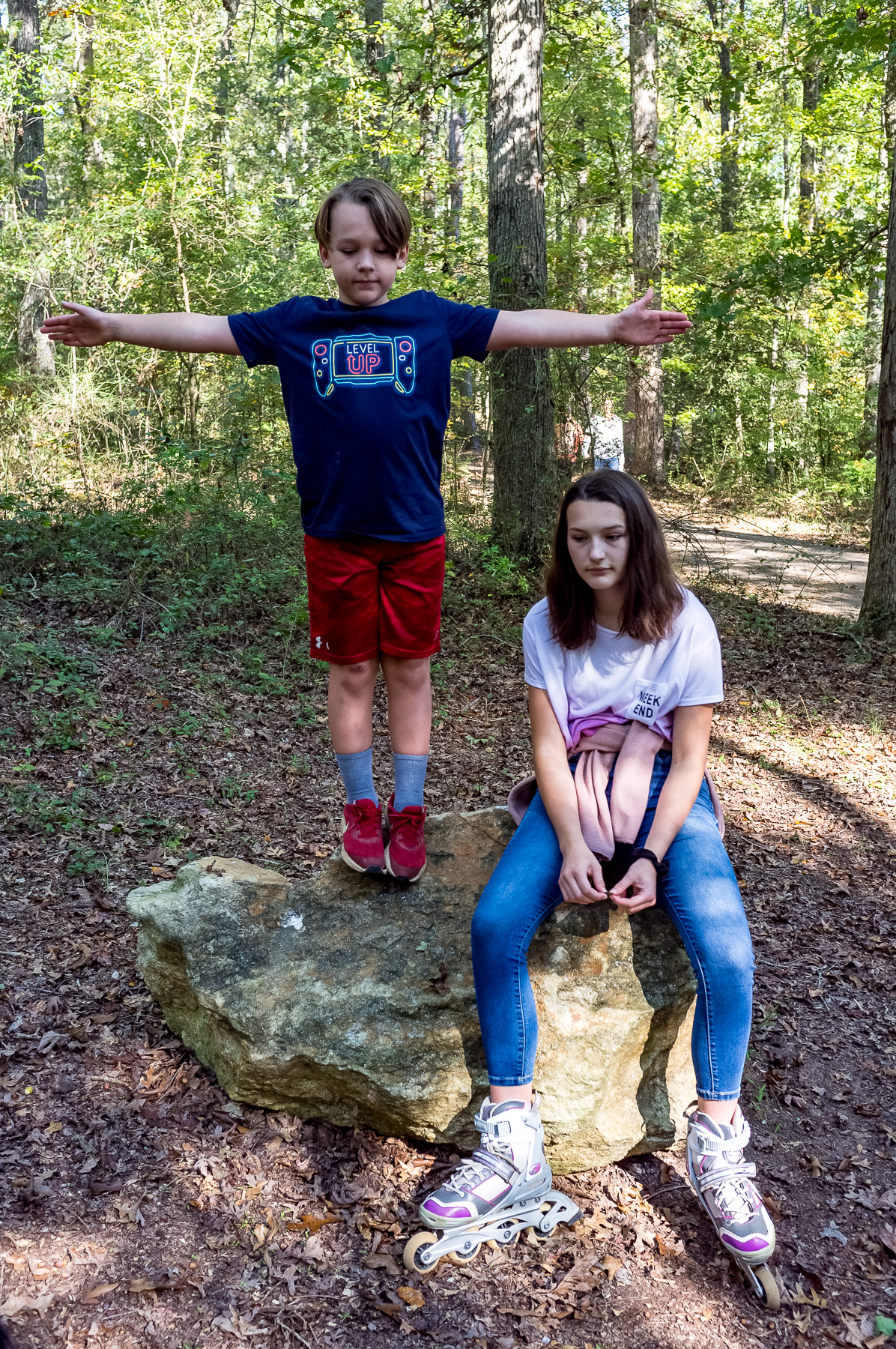

Sunday at the Park and on the Trampoline

Saturday Morning

Perfection

Our Country

Trump supporter in Utah says "Black lives don't matter" & coughs on protesters pic.twitter.com/P012t6EFhL

— Fifty Shades of Whey (@davenewworld_2) October 14, 2020

His justification:

All this has been lurking just below the surface in our country for years, and it just took one man to bring it all out. There are historical parallels that are too awful to mention.

Today in School

We had the PSAT today, so many students were out during class. No matter — it’s recorded and posted on Google Classroom.

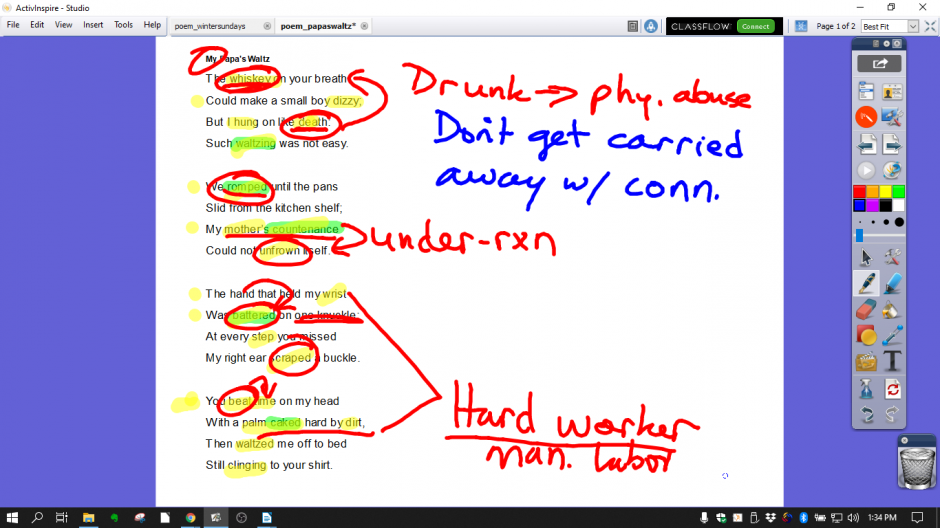

We began the day with a short open-note quiz on the two poems we just finished and on poetry in general. We followed that with a short viewing (about a minute) of the Stanford Viennese Ball’s opening waltz:

This was in order to provide students with some perspective about what a waltz looks like when we read “My Papa’s Waltz.”

Our reading of “My Papa’s Waltz” was a cautionary tale. At first it seems like so many words have connotations of abuse that the poem is actually about an abusive father.

- The “whiskey on your breath” line makes us think he’s inebriated.

- “Death” has obvious bad connotations.

- “Battered” and “beat” are abusive words.

The problem, though, is this is not a close-enough reading.

- Notice: his knuckle is what’s battered. Along with the “palm caked hard with dirt,” this suggests he’s a man used to hard manual labor.

- He’s beating time and nothing else — he’s tapping the boy’s head 1-2-3 to help him keep up with the waltz.

- The text shows he’s had something to drink; it doesn’t say he’s inebriated. (“Remember what that waltz looked like?” I reminded the students. “Do you think he could do that if he’d been inebriated?”)

- Note who puts him to bed: the father.

So this was a cautionary tale about reading too much into the connotations of a poem. Don’t overdo it. If there’s no evidence in the text, it’s likely not a valid interpretation.

Finishing the Toolbox

Yesterday was the cut day; today we assembled everything. I struggled to figure out how much to do and how much to let him do, to decide how many mistakes to correct and how many to let slide.

“Oh, Daddy, that nail is actually coming out of the bottom.” That’s one to correct.

“Daddy, I didn’t evenly space these nails.” Just pat him on the head and say, “It’s not a big deal, buddy.”

In the end, it wasn’t perfect, but he’d done almost all of it — a good reason to do your best Dr. Seuss character imitation. (“Daddy, why do so many of the characters go around with their eyes closed?” he once asked. I’d never really noticed that.)