Through a social media account dedicated to publishing old photos of Orawa, the region of Poland where I lived for seven years, I’ve discovered photographs of Lipnica Wielka from a time long before I was born, not to mention before I came to know and love the place.

Most of the photos are of the centrum area, which makes sense: it is literally the center of the village. From centrum, the village now stretches about four kilometers toward Lake Orawa and six kilometers to the base of Babia Gora, giving the name centrum both a geographical and functional significance. During the time these pictures were taken, those distances might have been different, but I doubt it: instead, there was likely simply more room between homesteads.

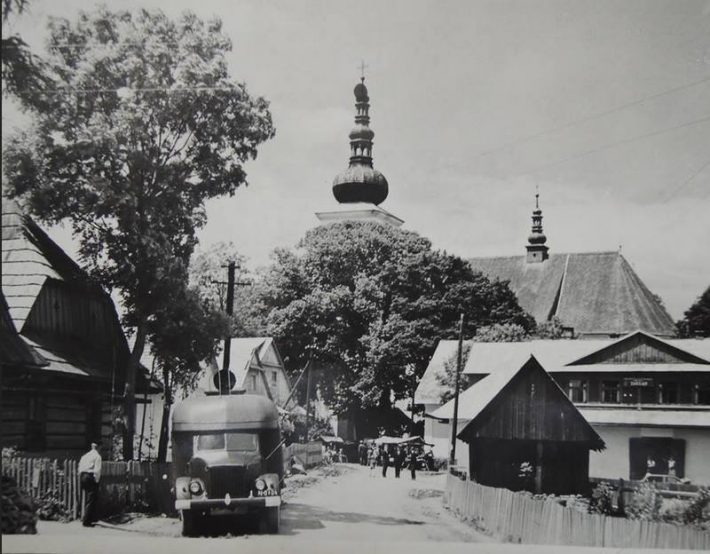

The shot from the sixties — the second and third houses on the left are still there. I’ve visited friends in both of them.

In one of them lived two of my students. I’d gotten to know their father, F, as he would come to a shop my friend S owned when I was there hanging out, drinking a beer, chatting with my friend. F was always insisting that I would have to come to visit him for a coffee; I was always putting it off.

I did visit him once. I was leaving S’s store when an eruption of yelling and what sounded like physical fighting spilled into the street, and F’s youngest son came running out, a look of panic and fear on his seven-year-old face. More yelling. I pushed through the gate and walked to the house. “Wujek!” I called out — I’d taken to calling him “Uncle” as my friend S did. “I came for that coffee you promised.” Just then, his son — whom I taught — came out of the house yelling back at him, his father in pursuit, his mother tugging at her husband. “Wujek, I came for that coffee,” I repeated, trying to sound as if I had no idea what was going on and just happened to choose that moment to take him up on the offer.

F saw me, stopped, and calmed immediately. “Get out of here,” I said in English to his son, “and take your little brother with you.”

Soon, we were sitting at a small table in their kitchen, his wife making coffee. When F left the room to retrieve something to show me — pictures? some kind of manual? — I said quickly to his wife, “Sorry to come in like this. I just thought I might be able to help.” The corners of her mouth arched upward slightly but said nothing.

The church in the thirties: that view is impossible now. There are several houses there, many of which weren’t even there when I first arrived in 1996. The village is expanding, with houses being built off the main road, which necessitates new roads, new infrastructure, new, new new. Such a strange juxtaposition to the numerous half-completed homes that dot the village — all villages in southern Poland — that have stood as empty shells for years, decades even, after the family abruptly moved to America. That stone road, though, is still there albeit paved.

Two images look strikingly similar to my first encounters: the old school in Lipnica looked exactly the same when I arrived. It was no longer in use, with the elementary school it used to house in the lower floor of the large, then-new school complex where I taught high school students. The volunteer fire department band used upper room for rehearsals, though, and many a summer evening, when all the windows were open, I could easily hear them in my apartment in dom nauczyciela behind it. Sometimes heated discussions replaced the music, but by the time my Polish was good enough to scratch out some meaning from my eavesdropping, they’d stop rehearsing there.

Except for the dirt road, the border looked almost identical as well. This was the small crossing that I never dared use because there was never any officers there to document my departure from Poland and my arrival to Slovakia. I was terrified at the thought of being caught in Slovakia without proper stamps in my passport or caught coming back into Poland without the appropriate stamps.

Once, I rode my bike there with K, and feeling mischevious, I stepped over the border briefly. If memory serves, K assured me that we could continue on the road without any worries, but in a way, that doesn’t sound like K.

Finally, there is a portion of the road that I recognize not because of buildings or anything else; I simply recognize the curve and slope of the road, with Babia Gora just behind it. So odd that I can recognize a coupe-hundred-meter stretch of road in a small Polish village simply from that.

It was the route I walked countless Saturday nights with friends as we headed to a discoteque housed in the empty rooms above one of the bakeries in the village. There was always such a mix there:

- Teens who were not yet of age (i.e., my students) who shouldn’t have been in there, but what else are they going to do?

- Men in their twenties and a few in their thirties — occasionally, older — who went to drink.

- Men in their twenties and a few in their thirties — occasionally, older — who went to drink and flirt with girls entirely too young for them.

- Young ladies who’d come in groups to dance.

- Young ladies who’d come in groups to dance and flirt.

I sat with my friends, drinking beer, talking to folks (occasionally students), watching people, making mental notes that eventually found their way into my journal.

All those memories embodied, strangely enough, in that little curve of road.