Kicking the Ball

Clover loves to play fetch with balls: tennis balls, volleyballs, basketballs — whatever. She prefers anything over a basketball because she cannot grasp it in her teeth and has to herd it up the hill of our backyard with her nose. This is why I personally prefer a basketball with her because it is much more amusing to watch her bring the ball back.

However, as enjoyable as playing ball with Clover is, she can really turn it into an annoyance. Any time anyone comes into the backyard, she thinks they’ve done so expressly to play with her. No other options are conceivable. So she runs to get the ball and drops it near your feet and backs off expectantly. She looks at the ball, looks at you, looks back at the ball. If you don’t kick it, she’ll run up, give it a little nudge with her nose, then back off again, ready to streak down the hill after the ball.

This is cute if you’re just out with your son, doing this or that. It’s less cute when you’re trying to do something, like build a fire or finish a swing. I try to accommodate her even then, occasionally kicking the ball for her or simply shove it away from me with the vague hope that it will roll down the hill that is our backyard and distract the dog for at least fifteen seconds.

I shouldn’t complain, though: I love our dog, even though I joke that I don’t. She’s stubborn and overly hyper; she gets jealous of any dog which is receiving giving attention; she plays rough and tries to boss smaller or large and more docile dogs about. Despite these minor shortcomings, it’s hard not to adore her: her jealousy just comes from her love. Her pestering just comes from a desire to play, which she rightly realizes we often enjoy as much as she.

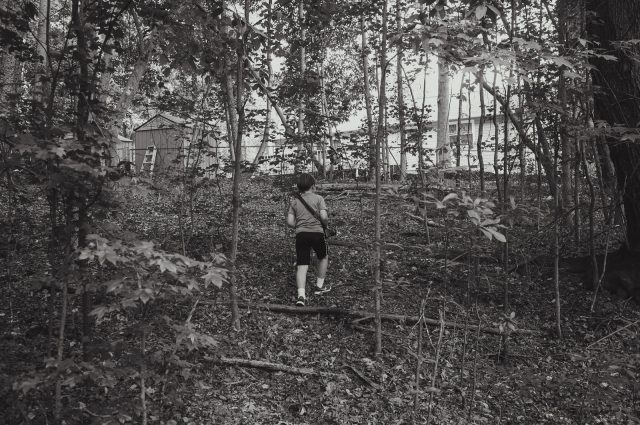

Shooting and Berries

During our morning break, the Boy and I went shooting in the backyard. He’s become quite the shot with his bb gun. While we were retrieving an errantly kicked ball (over the fence to the driveway, rolling down to the blueberry bushes), he decided to take a few shots at the archery target at the other end of the yard. From where we stood, though, he was shooting only at the side, a target of about 15-18 inches wide. He hit it the first time; he hit it the second.

“Man, I’m good,” he said.

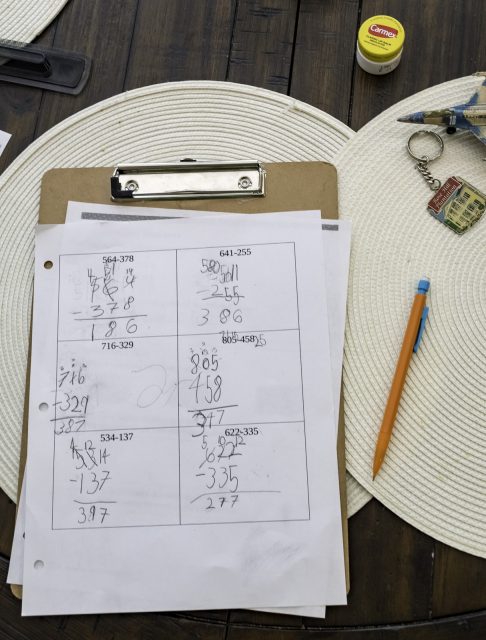

Yes, he certainly is. Sometimes we have to work on that modesty a bit, though. Yet, on the other hand, he is so lacking in confidence about some things — especially academic tasks — that perhaps a bit of bragging is a good thing. I don’t know.

I do know that he was impressed with the number of berries on our bushes and wondered what would happen if we were to try them now, long before they’re ripe.

“Go ahead and try one — but you probably won’t like it,” I suggested.

He tried one.

“Oh, oh! Yuck! It’s so hard and sour!”

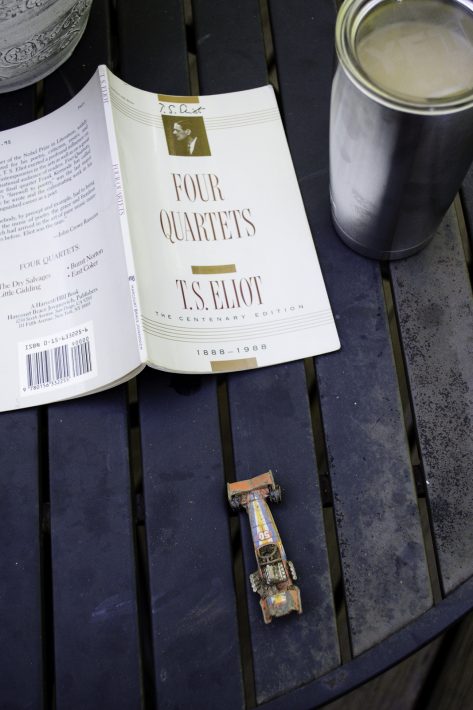

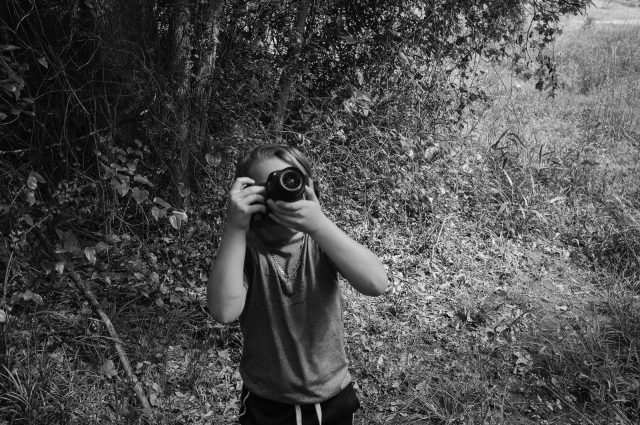

Photo Walk

After school was finished, the Boy was eager to go on a photo walk together. “I’m not so into photography anymore,” he explained, “but it’s still fun.” So I gave him the old D70 and took our little X100 for myself and off we went.

We passed the house where, for whatever reason, the owners are storing an old toilet on the back deck. The Boy loves the idea of a toilet on the back deck. “That way you can poop and be in nature!” That’s one way of looking at it — a very seven-year-old way at that. When we got to the house, he tromped boldly up to the fence, took a moment to compose his shot, and walked calmly back down. In the past, he didn’t really want to do that.

“What if they see me? What if they say something?”

I tried to explain: “The most they would do is to tell you not to take a picture of their house. In that case, you just smile, apologize, and say, ‘Sorry — I’ll delete it.’ Simple.”

And where are the pictures he took? I haven’t taken them off the camera. I’ve been trying to teach him to use Lightroom and use his edits as well, but we didn’t have time today to complete the whole project.

We had to hurry home for dinner.

My Hometown

I grew up in Bristol, which is a unique city as it sits on the Virginia/Tennessee border. The border runs right down the middle of the main street downtown, State Street. A divided city such as Bristol has unique features: for instance, sales tax in Virginia is much lower than that in Tennessee because Tennessee doesn’t have an income tax. Smart folks, then, live on the Tennessee side and shop on the Virginia side.

Back before Daylight Savings Time was an almost-nationwide phenomenon — I don’t know what else to call the arbitrary changing of the clock — one state used it and the other didn’t. That meant you could cross the street and gain or lose an hour.

When I first went to Poland in the Peace Corps, I stayed with a Polish host family in Radom for twelve weeks during training. The son was fascinated with State Street: “Does that mean if you commit a crime on one side of the city and the police chase you and you cross the border, they have to stop chasing you?”

The two-state status of the city is relevant now in the time of COVID-19 as Tennessee and Virginia are taking different courses through the pandemic. CNN had a story about it yesterday.