Quartets

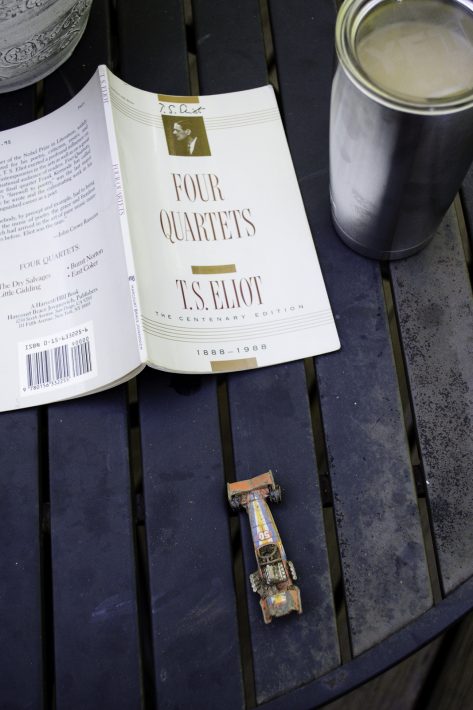

This afternoon, while cleaning up the kitchen, putting away groceries, and just generally puttering around the house, I discovered a BBC culture podcast that talks about, among other things, T. S. Eliot’s Four Quartets, a cycle of four poems that have, from the very first time I encountered them during my freshman year in college, utterly enthralled me. Naturally, I listened to it; naturally, halfway through, I was rooting around in the bookcase where we store such books for my thin volume of the poems.

Some passages of those poems seem pulled from the very fabric of existence itself, so fully do they capture the experience of being a finite human. In “Burnt Norton,” the first of the poems, Eliot writes of the frailty of the one thing that links us humans one to another: language.

Words strain,

Crack and sometimes break, under the burden,

Under the tension, slip, slide, perish,

Decay with imprecision, will not stay in place,

Will not stay still.

I read those lines in college at a time when I was growing very distrustful of language having been in a relationship that I ended largely because I felt like the young lady was lying incessantly, for no reason whatsoever. Was it compulsive lying? Was it even always conscious lying? Was it even lying? I could never figure that out, but I learned I couldn’t trust her, and when that happens, there’s only one thing to do.

The second poem in the cycle, “East Coker,” returns to this motif:

So here I am, […]

Trying to use words, and every attempt

Is a wholly new start, and a different kind of failure

Because one has only learnt to get the better of words

For the thing one no longer has to say, or the way in which

One is no longer disposed to say it. And so each venture

Is a new beginning, a raid on the inarticulate

With shabby equipment always deteriorating

In the general mess of imprecision of feeling,

Undisciplined squads of emotion.

“Is he reading my mind?” I thought. The poem seemed to be a summary of my growing interest in the idea of language itself. Such a strange thing — it’s the only thing we have that connects us to other people, yet it’s such a fragile connection, so easily manipulated and bent.

The Buried Car

This evening, as I was reading the poems again after dinner, the Boy brought me a little car he’d found buried in the backyard.

“I found it buried in Mommy’s flowers,” he explained.

“It was my car,” I said, wondering if he would remember that it had been among the mass of cars that Nana had saved from my childhood just to give to a grandchild.

“Really?!” He couldn’t believe it. “Why did you bury it out there?”

It’s so rare that we can see someone’s entire faulty thinking process from just one sentence, the entire line of thought backing up neatly, step by step, until the whole story is clear, and it was so different from reality. That was such a moment. I knew I could utterly perplex him with one short sentence.

“I didn’t bury it out there; you did.”

I could almost hear the gears clicking. He wrinkled his brow, cast his eyes upward, and his breathing quickened. “I did?”

Back to Eliot — the very next lines:

And what there is to conquer

By strength and submission, has already been discovered

Once or twice, or several times, by men whom one cannot hope

To emulate—but there is no competition—

There is only the fight to recover what has been lost

And found and lost again and again: and now, under conditions

That seem unpropitious. But perhaps neither gain nor loss.

For us, there is only the trying. The rest is not our business.

I had not really lost the car; he had not really gained it. He discovered something that he himself had owned, had played with, had possibly even treasured.

“Yes, you must have been playing with it when Mommy was working out in the flowers and you accidentally left it there. Or maybe you even buried it on purpose, and you just don’t remember.” More thinking.

“I did?”

“Yes.” And I could even imagine how it happened: E, with more than a handful of cars, following K around as she planted flowers or pulled weeds, never willing to let her get very far away from her, picking up everything to follow closely behind.

Nana told me I was the same way. Probably, we all are.

“You must have been playing with it when Mommy was working in the flowers.”

He shrugged, not convinced, still wondering, I think, how I knew it was mine. “Was it one of your favorites?”

True, I think I can remember when I got that car, which means an event likely forty years ago. When we went to our church’s annual fall retreat, we had two-hour church services every day. To keep me quiet when I was a child, Nana and Papa gave me a new Matchbox car every day at the start of the service. I believe that’s where this one comes from. But it could simply be that I just remember playing with that old car.

Are there any of my old toys I wouldn’t recognize? I rather doubt it in a way. Toys are so precious to children — at least they were to me and to my own children — that they form an integral part of our identities. Like the music we listen to as adolescents, the toys we love as children reflect our interest and how we see ourselves.

I didn’t tell him all that, though. Too much back story, and so much of it so very different from the reality the Boy experiences.

“Two-hour church every day?! Why would you do that?” I can hear him ask. Why, indeed.

Back to the Quartets, this time, from “Little Gidding”:

There are three conditions which often look alike

Yet differ completely, flourish in the same hedgerow:

Attachment to self and to things and to persons, detachment

From self and from things and from persons; and, growing between them, indifference

Which resembles the others as death resembles life,

Being between two lives—unflowering, between

The live and the dead nettle. This is the use of memory:

For liberation—not less of love but expanding

Of love beyond desire, and so liberation

From the future as well as the past.

It’s attachment to things that makes us remember those toys, I guess, and the sense that they are part of us — thus, attachment to self.