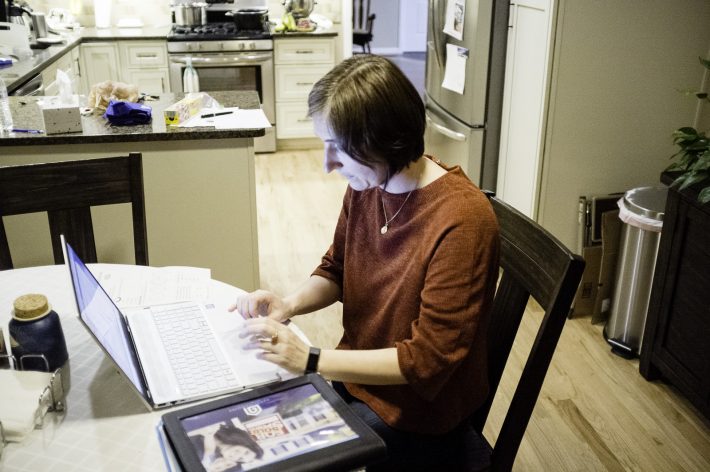

In the afternoon, after almost all the day’s necessities were behind us — shopping, a photoshoot at a local church for the diocesan newspaper, a soccer game (that I didn’t attend because I stayed behind to keep an eye on Papa, hence the lack of photos) — we went out to shoot L’s bow and arrows. K had gone to drum up some clients for her new venture in real estate, but the kids and I were, for all intents and purposes, done. Sure, I still had a consultation call with a client for a web site I’m building for her, but that was easily put off to the evening.

The Girl hadn’t lost her touch. Which is to say that she didn’t put a lot of arrows near the center of the target, but she didn’t miss the target entirely — which was the case when she first started shooting.

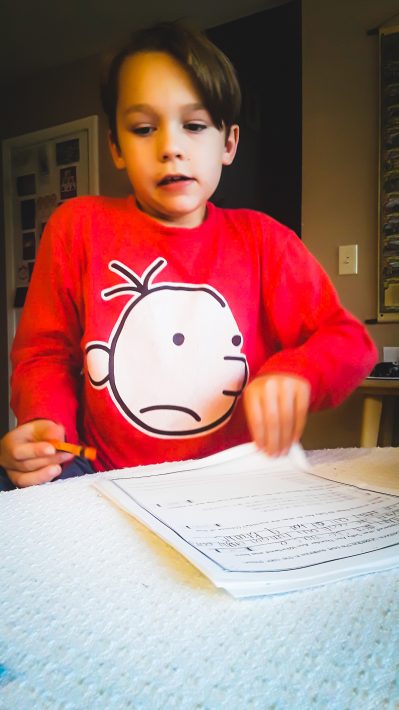

For the Boy, though, it was a different matter. He hit the target a few times — many shots fell ineffectually short, but he did hit the target a number of times. The problem was, though, that the bow was just a little too big for him, so he was not able to get enough pull on it, so not enough energy went into the arrow. So every single shot that did hit the target bounced off.

Understandably enough, it was a source of great frustration.

“Daddy, I can’t make any of them stick!”

What to do when your boy is frustrated and wants to quit? Make a joke of it.

“It’s almost like the target is against you, like it has a will of its own. Like it has some kind of Jedi power. ‘Nope,’ it says as your arrows strike. ‘Nah, not this time,’ it says the next shot.” And so on. Soon he was laughing and making his own jokes when the arrows flopped off the target.

“That one slammed into reverse and backed up!”