We were playing Monopoly this evening and the Boy bought his first railroad. It’s always his plan to try to get all four railroads. When L landed on the next railroad, she bought it for $200, then offered to sell it to E for $400; he accepted the offer. I tried to explain to him why this was a bad deal, that paying double for this railroad was not worth it at this point, but he was stubborn and would not listen.

“It might be worth it if this were your final railroad,” I told him. “As it is, it’s certainly not worth this much money just for the second railroad. There’s no guarantee that you’ll get either of the other two railroads.

A couple of hours later we were looking through a box of old collector cards that I had. There were baseball cards, football cards, basketball cards, and even, strangely enough, some Star Wars cards that I have gotten from somewhere at some point in my childhood. E asked me how much these cards were worth I tried to explain to him that I really didn’t have any idea because there was just no way of knowing.

“Where on the cards does it show how much they’re worth?” he asked.

“It’s not on the cards,” I explained. “It all depends on how valuable they are and that depends on how rare they are.”

“How could we find out?” he asked.

“We would have to go talk to an expert.”

“I think I know an expert.” He told me of a friend at school so that’s mini baseball cards. “A couple of them are worth a few million dollars.”

“How do you know that?” I asked.

“Because he told me.”

“Do you believe him?”

“No.” He thought for a moment then changed his answer.

“Does that make sense?” I asked.

“What do you mean?”

I tried to explain to him that if indeed the family had a card which is are several million dollars they certainly wouldn’t let the seven-year-old child keep it.

“Why not?”

“Because remember what I told you about Star Wars characters and every other collector item: they’re only valuable if they’re in perfect condition. If you bent it, or wrinkled it, or tore it, it would be worthless.”

“Why?”

“It’s just the way it is,” I sighed.

It’s all but impossible to explain to a seven-year-old how the scarcity of an item makes something valuable, something which otherwise would have no value, priceless. Baseball cards are just a bit of paper with a picture printed on them. Then again, change the word “paper” to “fabric” and it holds true for money: just a bit of material was a picture printed on it.

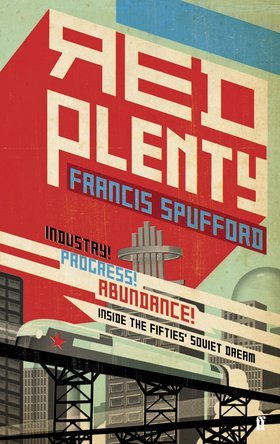

In the midst of all this, I’ve been re-reading Francis Spufford’s fantastic book Red Plenty, set in Khrushchev’s Soviet Union.

The premise is simple. When Khrushchev was ruling the Soviet Union. it seemed as if the Communist Utopia could indeed come to pass. A state-planned economy that would bypass all the uncertainty and unfairness of supply and demand capitalism seemed achievable. Vacuum tubes and algorithms made such calculations on such a scale achievable.

The book follows various characters as they weave their way through the creation of this Utopia, each playing their own part. Mathematicians, economists, biologists, Politburo members, Eisenhower, Khrushchev, and others all appear in the novel. All of the Soviet characters are searching for the formula that will make the magic Elixir of Plenty. Plenty of meat. Plenty of bread. Plenty of apartments. Plenty of cars. Plenty of everything.

Within all of this, the chief problem is how to assign value to both work and commodities. The book, which is part-novel, part-history, is filled with characters fictional and real; many events of the book are actual events in history. It’s nearly 500 dense pages telling the story of just over 70 years of men and women working feverishly to determine a mathematical and certain way of deciding value.

If they couldn’t do it, I’m not sure I can explain it to a seven-year-old in one evening.