Wednesday Virus

The Boy wanted to go to school today. He really wanted to go. Mainly because they weren’t going to be in school — it was field trip day to the local science center where they have a Tesla coil, explode hydrogen balloons, and generally thrill kids of all ages. But the rash he’d gone to bed with, the little splotches on his cheeks, had spread all over his body.

“E, we have to go to the doctor,” K explained.

“But it’s nothing. Look — it will go away in no time.”

She tried to explain to him the risks of passing something on to other children.

“They won’t get it! I know they won’t!”

In the end, he lost. The doctor said it was a virus going around. “He’s through the worst of it, but you should keep him home today.”

For today’s pictures — fifteen years ago in Budapest and Poland with Nana and Papa, when they came for our wedding. I was going through pictures this evening, revisited these, and did some editing.

Monday

When I got home from work, I asked the Boy if he wanted to go play outside — to go exploring or something similar. With the coming cold spell, we have to make the most of the relative warmth while we have it. He was eager to go, and he was eager for L to join us.

He’s always talking about doing things as a family. “When can we go on a family bike ride?” “When can we watch a family movie?” “Can we go on a family walk?”

L, now twelve, is starting to show typical teenager behavior, like a reluctance to hang out as a family all the time. She enjoys it, but she also loves “alone time” as she calls it.

Today, though, we were able to talk L into going exploring with us. The Boy, utterly thrilled, took the lead and instructed L how to cross the creek, how to scale the bank (of course she found her own way), how to navigate the thorny places.

Standing Still

Coming home this evening, L was playing a life simulator game on her iPod and mentioned that she was now forty-seven.

“You’re older than I am,” I laughed.

“No,” she explained, “you can change your age at the click of a button.”

“It’s a good thing you can’t do that in real life,” I replied.

What I had in mind was what I thought at her age: I can’t wait until I’m X years old. That always looking forward, always longing to be a little older, which struck around age six or so. “When will I be big?!”

“No, it’s a good thing,” she agreed. “I’d never press the button then.”

She was taking the opposite option, to which I replied, “Well, at some point, I’d just click the button for you.”

“Why!?” came the incredulous response.

“Because you’re not going to mooch off me for the rest of your life.” We both laughed a bit, but I got to thinking about what it might be like if we could have that option, if we could just stay one age for as long as we wanted to.

On the one hand, the nostalgic in me would love that, but what moment? While looking at the “Time Machine” posts at the bottom of the site, I discovered this shot from 2013:

The Girl was just a little younger than the Boy is now, and I hadn’t thought about how much different she was then than she is now. A six-year-old and a twelve-year-old are completely different people in many ways. Looking back, I can see traces of personality traits she now exhibits all the way back then, but the reverse wasn’t true: I had no idea how much she would change in six years (and, of course, how much she would stay the same).

Yet, within that little clump of nostalgia is a nightmare: if I chose that moment, then what about all the wonders that have happened since? Being stuck in one moment, after all, is what Bill Murray’s brilliant Groundhog Day is all about. But it’s more complex, because that film is really about being stuck in that moment without enjoying that moment, being stuck in a moment when all one does for one’s whole life is look toward other, more exciting moments.

I think I’ve lost the thread of where I was going with this, and that’s kind of the point perhaps. The key to life, rediscovered once again, is getting stuck in the moment by enjoying the moment so much that one doesn’t want to move forward but accepts the simple fact that that forward motion is, in fact, the moment itself. Axiomatic. The present doesn’t exist — it’s a sliver between the past and the future. That old chestnut. Living the moment means accepting that it’s just that — the moment.

So what to do in the moments of this afternoon? Go exploring, of course. Play in the backyard, of course. Enjoy the short bit of time we had between visits to Nana and visits to Papa and trips to church and more trips to church and cooking and lesson planning and everything that makes Sunday Sunday.

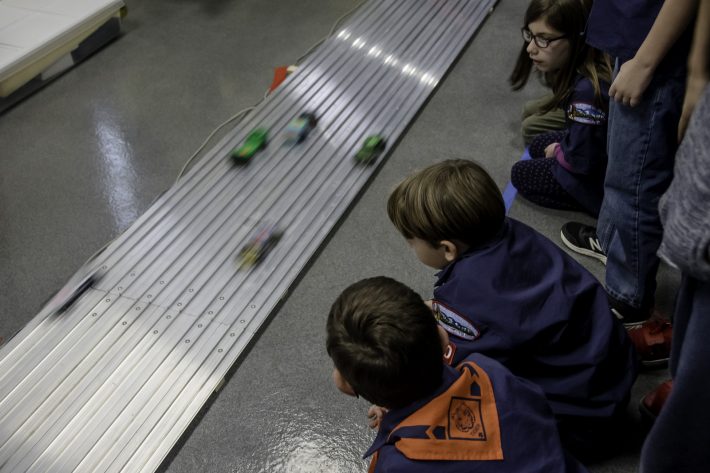

Last Game and Pinewood Derby

The Boy played his last game of his first basketball season today. He didn’t make a basket, though he took a shot. He had a couple of turnovers. At one point, he was defending his assigned player even though his team was on offense. All signs of a new player still finding his way in a game that he really doesn’t fully understand. But he played with such heart. He did everything his coach told him (coaches at this level are allowed on the court, as soccer coaches at that age group are allowed on the field), and oblivious to the above facts, he enjoyed it, which is what counts most.

“I know what I’m saving up for,” he declared earlier this week. “A basketball goal for our house.” The only problem: we don’t really have a place to put a goal. But our neighbor has a small court set up on his driveway — we’ll have to find the time to go there more often, K and I decided.

In the early evening, we went for the Boy’s second pinewood derby. We’d been working on the car this week, and the Boy went into it with a lot of confidence. At the very least, he was sure, we would have the best-looking car. He’d decided on a humvee, which made for easy painting and it looked pretty good when it was all said and done: I did the cutting and some of the sanding; he did the painting and some of the sanding.

When the racing started, his car finished consistently in fourth place out of the six cars racing. That meant he wasn’t the fastest but wasn’t the slowest either. A more competitive spirit would equate those terms with “best” and “worst,” but I try not to look at it that way because I’m only somewhat competitive.

Sometimes I wonder, or rather fear, that his lack of competitiveness comes from a lack of confidence, that he feels he has no chance of winning anyway and so why not cut one’s losses and not appear to be terribly worried about the results of inherently competitive events. That’s how I was, I think, when I was a child and teen. It wasn’t that I worried about losing; I just didn’t want to get embarrassed, to get beaten into the ground, so to speak. In gym class during high school, when we had basketball, I was reticent to participate because I was never all that good. I even refused to dress out some days, making the excuse that because I was on the swim team and got plenty of exercise that way, I really didn’t even need the activity. Swimming was different, though, because I had success in the pool and felt more confident there.

Is that compensation or something more concerning? I don’t really know, and I’m honestly not terribly worried about it. I think in the end, all of us with a little competitive spirit in us do that.

Zab Revisited

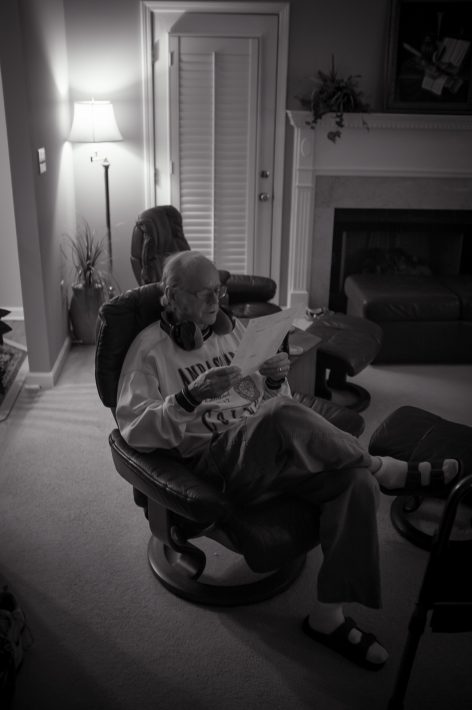

Lunch with Nana, Dinner with Papa, and Work

With Nana still in rehab and Papa alone, we take care of them the best we can. Poor Nana has to put up with institutional food, which, she claims, is not terrible, but which I also know is not great. Poor Papa can cook eggs and warm things up in the microwave, but he’s never done much more than that.

This afternoon, since it was MLK Day and the kids and I had the day off, we took over a favorite chicken sandwich for Nana and cheered as we saw evidence of an ever-increasing appetite.

In the evening, we went to make dinner at Papa’s. We either cook something here and take it over every night or take everything there to cook.

Other than that, an uneventful day. I spent an hour in the morning planning lessons for the next several days (this week and a little beyond) for one class and another hour in the afternoon planning for another class, plus half an hour in the evening grading papers.

This year, I’ve kept track of all my out-of-classroom hours — planning, grading, going to meetings, etc. For this first semester, I’ve spent 115 hours above the 40-hour work weeks. That’s just a little over half a day shy of three full work weeks. If I keep this pace up — and I see no reason why I wouldn’t — I’ll have spent close to six weeks’ worth of time outside the classroom doing work. Add to that the half-hour morning duty I have every third week, which makes 2.5 hours a week or 30 hours for the year, and I’ll have 260 hours of additional work on top of my normal work week. That’s six and a half weeks of work. I have about nine weeks off during summer break, but I probably spend an additional 40 or so hours over the summer planning for the coming year. (I’ll keep track this summer.) That’s seven and a half weeks of work, which means my summer “vacation” is really not much of vacation — I’ve just put in the hours in advance.

I don’t say this to complain. Much of the time I spend grading is because I try to push my kids as hard as I can, which produces a lot of material for me to assess. I have a reputation to keep up, after all: students tell me that they’ve heard since they entered the school in sixth grade that I’m the most demanding teacher in the school. I don’t know about that, but it certainly doesn’t hurt one’s sense of self-worth to hear something like that. In other words, I could do less work and get by, but then it wouldn’t be the Dread Teacher Mr. Scott’s.

Finally, I must have been under a rock, but I just learned of Mary Oliver’s death tonight, listening to the news in the car. A poet of fairly simple verse, she’s always a great choice for thirteen-year-olds. In past years, when I had students put together annotated portfolios as their culminating poetry unit project (which is not to say I have my students read poems for one dedicated unit and then neglect poetry for the rest of the year, but I find it’s good to spend three or four weeks focusing on what makes poetry poetry to equip them for the rest of the year), almost every student included an Oliver poem, and they all said they liked her because she’s easy to understand. I personally have always liked poems that require a bit more digging, but that’s not to say I’m a big fan of someone like Louis Gluck, someone who writes poetry that is almost impenetrable. My favorites — Bishop, Heany, Levine, and the like — require some thought, require a bit of effort, but always reward with a moment of stunned epiphany.

And since I’ve been talking about work, why not include Levine’s poem on the same subject:

Five Years Ago

What For Dinner?

Rainy Saturday

The Boy finished his Jurassic Park Lego play set yesterday. Today, it fell apart, in part because of a poor design. K helped him put things back together; I added some stability to make sure it doesn’t happen again.

In the afternoon, we finally took down the Christmas tree while watching ski jumping from Zakopane.

Gallery of Shakespeare

I posted the seven quotes around the room, seven key passages from the second and third scenes of Romeo and Juliet act three. The kids spread out in groups of three or four and took four to five minutes looking at the quotes, completing three steps:

- Define up to three words on the Post-It note.

- Note any language tricks (inversions, elliptical constructions, parallel construction, figurative language, etc.).

- Discuss and note what earlier passages in the play this reminds you of; mark specific elements.

After time was up, they rotated to the next quote. (It’s called a gallery walk in edu-speak.)

The kids read Juliet’s thoughts about Romeo:

Come, gentle night, come, loving, black-brow’d night,

Give me my Romeo; and, when he shall die,

Take him and cut him out in little stars,

And he will make the face of heaven so fine

That all the world will be in love with night

And pay no worship to the garish sun.

O, I have bought the mansion of a love,

But not possess’d it, and, though I am sold,

Not yet enjoy’d: so tedious is this day

As is the night before some festival

To an impatient child that hath new robes

And may not wear them.

And sure enough, they picked up on the parallels with Romeo’s words in the balcony scene:

But, soft! what light through yonder window breaks?

It is the east, and Juliet is the sun.

Arise, fair sun, and kill the envious moon,

Who is already sick and pale with grief,

That thou her maid art far more fair than she:

Be not her maid, since she is envious;

Her vestal livery is but sick and green

And none but fools do wear it; cast it off.

They read Juliet’s furious reaction to the news that her newlywed husband killed her beloved cousin:

O serpent heart, hid with a flowering face!

Did ever dragon keep so fair a cave?

Beautiful tyrant! fiend angelical!

Dove-feather’d raven! wolvish-ravening lamb!

Despised substance of divinest show!

Just opposite to what thou justly seem’st,

A damned saint, an honourable villain!

O nature, what hadst thou to do in hell,

When thou didst bower the spirit of a fiend

In moral paradise of such sweet flesh?

Was ever book containing such vile matter

So fairly bound? O that deceit should dwell

In such a gorgeous palace!

And they caught the parallel with Romeo’s words in the first scene:

Here’s much to do with hate, but more with love.

Why, then, O brawling love! O loving hate!

O any thing, of nothing first create!

O heavy lightness! serious vanity!

Mis-shapen chaos of well-seeming forms!

Feather of lead, bright smoke, cold fire,

sick health!

Still-waking sleep, that is not what it is!

This love feel I, that feel no love in this.

And they actually think it’s, to use their words, pretty cool.

Five Years Ago

No, six — I forgot it was 2019. Papa was in the hospital, recovering from major surgery on his lungs. Now, six years later, it’s Nana’s turn to spend some time in the hospital and rehab.

I know she would have passed. Gladly.

Sunrise

Wednesday Night Inferring

A busy day for everyone culminates in us arriving separately at home after seven, two hours after we normally eat dinner. After school, a long meeting, and a visit with Nana (out of the hospital and back in rehab — hurrah!), I’d stopped for something for us to eat; after work, shuttling the Girl to choir practice while taking the Boy shopping, running the Boy to basketball practice after dropping the Girl off at volleyball practice, then picking everyone up, K arrived shortly after.

As we ate, the kids and I decided that K’s plan for the rest of the evening was flawed.

“I’ll put away all the groceries and then go to bed if you’ll put the Boy to bed.”

“Nope. I’ll put away the groceries while you take a hot bath, and then I’ll put the Boy to bed while you go to bed yourself.” L and E agreed — Mama needed to call it a day. As I was bustling about the kitchen, I remembered it was garbage night.

“L, take the garbage and recycling out,” I said, expecting a little fussing.

“Okay.” Nothing more.

She came back in, a little whiny, and said, “E always takes out one of them. Can he take out the recycling? I’ll go with him.”

“No, sweetie, it’s late. Just do a little more than you have to.”

“Oh, okay.” Nothing more.

From this, a simple inference: our daughter really is growing up. She’s not just sprouting vertically (she’s almost 5’4″ now); she’s not just developing into a young woman; she’s maturing. With my nose pressed to the ever-present every day, I forget that sometimes. It escapes me.

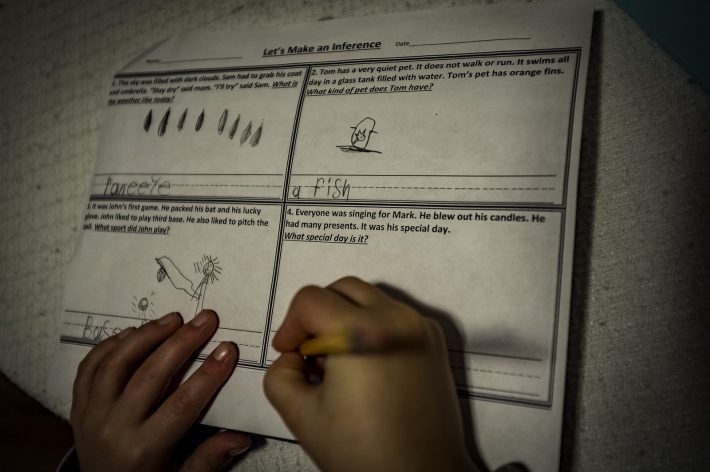

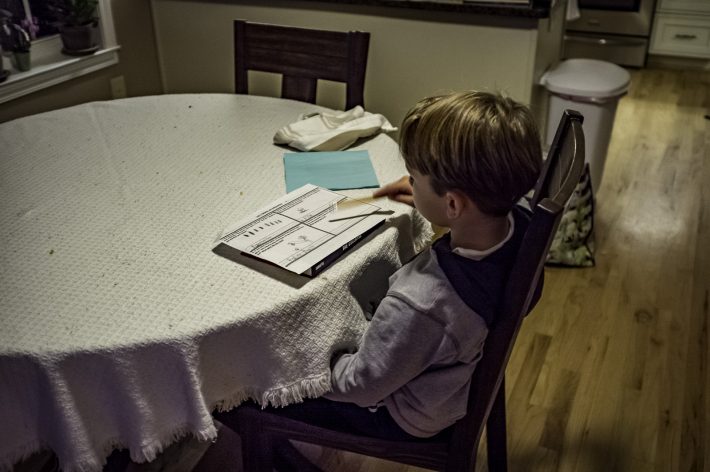

While all this was going on, the Boy had started his homework.

“What are you working on tonight?” I asked him.

“Inferring. We learned it today.”

As an English teacher, I’ve been working on the Boy’s (and the Girl’s) inferring skills for years. I taught him the word; he must have forgotten. The teacher did a better job today. “What’s that?” I asked.

“Making a good guess.”

Not a bad definition. I usually tell my students it’s “making a reasonable guess based on evidence.”

And there you might notice something: I teach eighth grade; my son is in first grade. Am I really teaching inferring again? Well, I’m not teaching inferring — they know what it is. But we’re still practicing it. Like mad. Especially (really, that should read “solely”) with my lower-achieving students. I give them a text like this:

Every day after work Paul took his muddy boots off on the steps of the front porch. Alice would have a fit if the boots made it so far as the welcome mat. He then took off his dusty overalls and threw them into a plastic garbage bag; Alice left a new garbage bag tied to the porch railing for him every morning. On his way in the house, he dropped the garbage bag off at the washing machine and went straight up the stairs to the shower as he was instructed. He would eat dinner with her after he was “presentable,” as Alice had often said.

I then ask a question: What type of job does Paul do? How do you know this? I have the students back up their answers with three specific pieces of evidence from the text, then explain how that evidence is evidence. A good student response (an actual student response) looks like this:

Paul is a farmer.I know this because he is wearing muddy boots. Wearing muddy boots is evidence that he is a farmer because if he were to work in an office or inside he wouldn’t have muddy boots. Also, he is wearing overalls in which he would not have been wearing if he was working inside. Finally, Paul’s overalls are dusty and most farmers work a lot outside so he must have gotten dirty from working outside.

So I applied the same thing to the Boy’s work. The same thing — a text followed by a question:

Everyone was singing for Mark. He blew out his candles. He had many presents. It was his special day. What special day was it?

E read the text and said, “It’s his birthday!”

“How do you know this?” I prodded.

“Because he got presents.”

“But we get presents at Christmas as well. How do you know it’s not Christmas?” He looked stumped for a moment, so I told him what I tell my own students: “Go back to the text. Find something in the text that shows it’s not Christmas.”

He read a while, thought a while, then said with a smile, “Because it says it’s his special day, not everyone’s special day. Christmas is everyone’s special day.”

I thought he’d pick up on the candles. That’s the more obvious piece of evidence. He went the more subtle route.

“That’s great. A very good observation. Now, can you find a third piece of evidence?”

Again, he looked, read, thought. “The candles. You don’t blow out candles on Christmas.”

After a tiring day, what a perfect ending.

New Legos

The Boy collected a bit of money for Christmas, and it’s been gnawing at him ever since. He wants to spend it. Badly. But he has a way of spending his money on items that just don’t last. K and I let him make those decisions once we’ve advised him, like buying a radio controlled car that was clearly of poor quality and obviously wouldn’t last long, then we try to help him reflect on the wisdom of that decision. He deemed the radio controlled car a poor decision.

With that in mind, we tried to steer him toward something that would last a bit longer. Given his love of Legos, it wasn’t that difficult. The difficulty came in choosing which enormous set he’d actually buy.

He went with a Jurassic World set, even though he’s never seen any of the movies.

“Can I watch one of the movies?”

“No, it will only frighten you.”

That’s as far as it’s gotten, but one doesn’t have to have seen the film to enjoy the Lego set. And he knows enough about the movie to make proclamations like, “I’m going to go against the rules: the dinosaurs are going to be friends with the people, not enemies.”

46

As of today, I’m on the back half of my forties, the downhill slide to fifty. Truth be told, it’s all been a slide, year to year.

It doesn’t seem like I’ve changed that much since the time I worried about the things the Boy worries about: how do I compare to the other boys? Am I as fast? Am I as coordinated? Am I as brave?

How do you console such worries? How do you reassure your son in this hyper-masculine culture about his fears of not measuring up to the other boys? The truth is, I not only worried about such things when I was young but continued stacking myself up against others and finding myself coming short well into my twenties thirties forties. I think most people who tell you they don’t do that are lying, probably to themselves first of all.

Life is not kind to most little boys like E, boys who are actually sensitive to others’ feelings, who can spontaneously show compassion and empathy. Who take a little while to settle into new sports. Who are so scrupulous about following rules that they ask daddy when on the road, “Daddy, how fast are you going? Are you speeding?”

I don’t have answers. I don’t even know if I understand the questions.

K and I talk about it. We encourage him. We support him. But we’re not there on the playground when he’s struggling to keep up with the other boys as they run about. We’re not there when kids are mindlessly cruel, and he struggles to understand why people could be so mean.

Good souls win in the end, don’t they? I look around the world and struggle to find an answer to that question other than, “Afraid not.”

Zakopane, 20 Years Ago

Pre-Bed Building and Reading

Eight Years Ago

Revisited

In my journalism class, we’ve decided to shift from pure journalism to a bit of literary nonfiction, so we began the day with a writing exercise. I provided a starter and fifteen minutes to write: “During winter break, I learned…”

I wrote along with them and found myself thinking again of Bida and so began writing again about Bida:

During winter break, I learned anew that love and pain are often so closely twined that one cannot separate the two, that tugging on one brings the second along with it. I learned all this watching and participating in my daughter’s grief as our family cat slowly died as she lay on our couch.

We’d had Bida for ten years. My daughter had never known life without that gray, grumpy, yet sweet rescue cat. She looked pitiful when we got her, hence the name, which means “poor little thing” in Polish. She looked even more pitiful as she lay dying, thin, slow, her bones protruding, her long gray hair matted because we could no longer brush her without causing her pain.

When we arrived home that night, my wife went to check on her in the room in the basement where Bida always loved to sleep. In a panicked voice, she called me downstairs. The poor cat had fallen off the bag of insulation that she loved to sleep on and landed on her back, wedged between the bag and some shelving. I thought she was already dead, but when I pulled her out gently, she shuddered, gasped, and began breathing in shallow breaths.

“Go get the kids,” I told my wife. “They’ll want to say goodbye.” She headed upstairs while I gently carried Bida to the couch in our basement family room and lay her down on the middle cushion. The four of us sat around the old, ornery cat for two hours as her breathing slowed, then stopped.

The first to come running from upstairs was L, my daughter. She was already beginning to cry, and when she saw Bida, the cat that had been around for as long as she could remember, she broke down into a sobbing, shuddering cry.

“No, Bida!” she shouted, dropping to her knees beside the couch and throwing an arm protectively but gently over the cat, who lay with her eyes open, her mouth gaping, the only movement being her rib cage that went up and down, up and down, up and down. “No, Bida! No!” she cried, her body shaking more and more violently.

I’d never been a big fan of that cat. I put up with her because L loved her so. But in that moment, watching my daughter wrecked with pain, her face a puddle, her voice almost instantly hoarse from crying, I realized I loved that cat because she loved that cat. I understood that I was near tears because she was in tears, and even because I was sad to see that grumpy cat go, to see that sweet cat suffer, to see my daughter suffer along with her.

When you love something, you open yourself up to pain because of that. You will feel that person’s pain with them; you will feel the pain of separation; you will eventually feel the pain of ultimate loss.

To love someone is to love their mortality, their temporariness, and the ________ness of everything they love.

A first draft — shows some promise, but nothing spectacular. That’s the idea.

Afterward, I had students choose the sentence they like most, the sentence they’re most proud of. “Be prepared to explain to a partner why you like that sentence, why that sentence fills you with a bit of pride,” I instructed. For my own sentence, I chose the first one: “During winter break, I learned anew that love and pain are often so closely twined that one cannot separate the two, that tugging on one brings the second along with it.”

“I like it because of the word ‘twined.’ I don’t think I’ve ever used that word, and it somehow provides a theme for the whole piece that I could go back and incorporate — images of thread, fabric, sewing, weaving, and so on,” I explained.

It was just the final lesson of a day filled with successful engagement from all students. I always worry a bit about how students will perform that first day back, and I’m always impressed. And then ask myself, “Why are you always worried? They’re always great!”