Evening

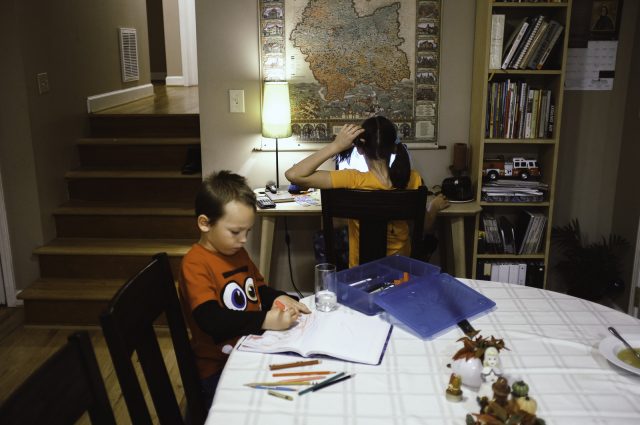

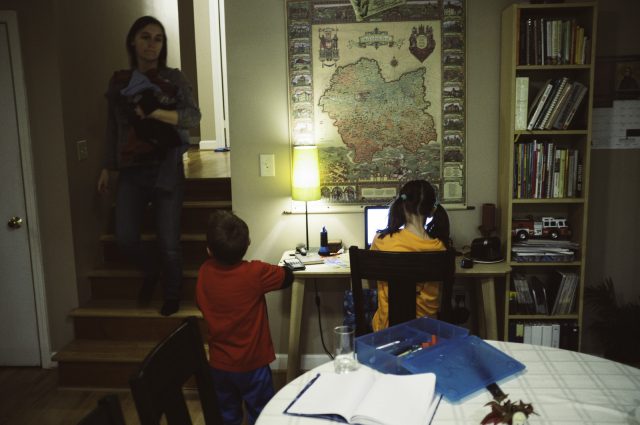

The kids are both at an age that they can find something to do all by themselves. The Boy less so, since he’s only five; the Girl more so, because she’s nearing her teens.

This evening, the Girl was researching prices for an electronic item she is saving up for. She’s saved for several items in the past: a Barbie camper, a Barbie bike, and others. Those items are long gone, as well as the dolls which they accessorized. I hadn’t thought about that, though, until I sat down to write this: it’s been so long since she’s played with Barbies that I’d forgotten, on some level, that she ever had. More evidence of that strange way we tend to fall into thinking that the way things are now is how they always have been. And always will be. Remember a Barbie camper reminds me that things change.

The Boy soon contented himself with drawing. I’m not sure where the urge came from, but he suddenly wanted to draw cupcakes.

“Okay, Google, show me cupcakes” he commanded our Chromebook. It’s become a favorite activity: “Okay, Google” activates the voice search, and off he goes. It’s a blessing and a curse: it allows him to research things he wouldn’t be able to investigate otherwise due to his still-blossoming literacy, but it could lead to a kind of laziness if not monitored as he learns to write.

After L made some decisions about which iPod was within her budget, she sat down at the piano and began picking through some songs. She stopped taking piano lessons at the end of the school year, but dear friends’ visit this weekend got her interested again, I think. At least on some level.

I’m a little torn on the whole issue: there’s an argument to be made for insisting that a child learn a musical instrument. But that whole argument is made moot by the fact that the Girl sings three hours a week in the church choir. Let her find her passion, a wiser voice says. Let her follow that.

Interpretation

My English I Honors students have just finished up a four-week poetry unit, which is in a way one of my favorite units we do. It’s not just that I love poetry, which I do, or that I hope to instill in them an appreciation of or even love of poetry, which I do, but it’s also a one of the units where we all see real growth in students’ ability to read and think critically.

At the start of the unit, there are the concerns: Some suggest they cannot understand poetry. Some suggest poetry is just about emotions. Some suggest that learning about poetry has no practical value later in life.

To the first concern, I always point out that learning to read increasingly challenging texts with greater levels of intentional ambiguity is just like everything else: it takes time and practice. I assure them that I’ll give them some skills — some tricks, I call them — that will help them ease the process.

To the second suggestion, I point out that while emotion is a critical element in a lot of poetry, it’s not the end of poetry in itself. It’s a means to an end. The emotion one finds in poetry is not what it’s about — except for some confessional poetry, of course. Even then, there’s always something bigger. I don’t tell them then, but what I’m referring to of course is the lyric moment of a poem, that point at which the reader has an epiphany because the speaker has an epiphany. (I am speaking of modern poetry, of course. When we move back into the nineteenth century and beyond, lyric moments tend to disappear a bit. Just a bit.)

The third worry is easy: No, you won’t read and interpret poetry your whole life, but you will need the skills — picking up on connotation, determining tone, reading for changes in mood — your whole life. No matter what you do, I say, no matter what the job, you’ll need these skills.

So we dive in. We read Elizabeth Bishop and Billy Collins, Dylan Thomas and Theodore Roethke, Langston Hughes and Howard Nemerov, Robert Hayden and in preparation for Romeo and Juliet, Shakespeare. There are others, but I’ve found it most fruitful to read less and read more deeply than read more and only skim over the surface. We read poems and then go back to them again when we’ve learned another skill. We read poems once, twice, three times — again and again and again.

Then comes the test. A simple, four-question test. “Four questions, Mr. Scott?! Only four?!” they all reply when we prep for it. I give them two poems, both by W.D. Snodgrass: “Momentos, 1” and “A Locked House.”

Momentos, 1

Sorting out letters and piles of my old

Canceled checks, old clippings, and yellow note cards

That meant something once, I happened to find

Your picture. That picture. I stopped there cold,

Like a man raking piles of dead leaves in his yard

Who has turned up a severed hand.Still, that first second, I was glad: you stand

Just as you stood—shy, delicate, slender,

In that long gown of green lace netting and daisies

That you wore to our first dance. The sight of you stunned

Us all. Well, our needs were different, then,

And our ideals came easy.Then through the war and those two long years

Overseas, the Japanese dead in their shacks

Among dishes, dolls, and lost shoes; I carried

This glimpse of you, there, to choke down my fear,

Prove it had been, that it might come back.

That was before we got married.—Before we drained out one another’s force

With lies, self-denial, unspoken regret

And the sick eyes that blame; before the divorce

And the treachery. Say it: before we met. Still,

I put back your picture. Someday, in due course,

I will find that it’s still there.

We read it together, make sure there are no unknown or confusing words, then move on to the second poem.

A Locked House

As we drove back, crossing the hill,

The house still

Hidden in the trees, I always thought—

A fool’s fear—that it might have caught

Fire, someone could have broken in.

As if things must have been

Too good here. Still, we always found

It locked tight, safe and sound.I mentioned that, once, as a joke;

No doubt we spoke

Of the absurdity

To fear some dour god’s jealousy

Of our good fortune. From the farm

Next door, our neighbors saw no harm

Came to the things we cared for here.

What did we have to fear?Maybe I should have thought: all

Such things rot, fall—

Barns, houses, furniture.

We two are stronger than we were

Apart; we’ve grown

Together. Everything we own

Can burn; we know what counts—some such

Idea. We said as much.We’d watched friends driven to betray;

Felt that love drained away

Some self they need.

We’d said love, like a growth, can feed

On hate we turn in and disguise;

We warned ourselves. That you might despise

Me—hate all we both loved best—

None of us ever guessed.The house still stands, locked, as it stood

Untouched a good

Two years after you went.

Some things passed in the settlement;

Some things slipped away. Enough’s left

That I come back sometimes. The theft

And vandalism were our own.

Maybe we should have known.

The questions:

- Identify tone and tonal shift of each poem. Make sure you quote specific passages of each poem in order to provide evidence.

- What is the lyric moment of each poem? What epiphany does the speaker have in each poem?

- Compare and contrast the two poems. How are the topics, tones, and lyric moments similar? How are they different?

- The author of these poems was an early writer of what’s called “confessional poetry,” in which the “I” in the poem is very often the poet himself/herself. It involves writing not about what’s going on in the world but what’s going on in the heart and mind of the poet. What can you infer about the author if we assume that the “I” in each poem is the poet himself?

These are somewhat tricky poems. “Momentos, 1” has a couple of tones in the first part of the poem that are then echoed in mutated form in the second half.

“A Locked House” uses a long, extended metaphor that, being a metaphor, is never expressly explicated. Experienced readers immediately see that the house is a metaphor for the speaker’s and his wife’s marriage, but thirteen-year-olds don’t always see that at first.

Flood

The Lost Art

You want to enter every conversation assuming you have something to learn.

Afternoon Downtown

Conestee Afternoon

Thanksgiving 2017

12:50

Three hours in the kitchen yesterday morning; five hours in the kitchen this morning; I’ve listened to over half of Paul Auster’s Sunset Park in the meantime. (Does he ever write anything that doesn’t have a writer in it? I love his style, but sometimes I get the feeling I’m just reading variations on his autobiography. This one, so far, has no connection to Paris.) I’m thankful that it’s almost done. The turkey is in the oven; the dressing is cooling; the soup and cranberry sauce (this year stewed spiced chai with a bit of bourbon as an experiment) sit in the refrigerator; the broccoli casserole (yes, there simply must be a casserole or else it’s not Thanksgiving) is ready to go in the oven; the giblet gravy is almost ready. It’s time for a cup of coffee, a pipe of tobacco (after years of smoking English and Virginia/Perique blends almost exclusively, I’ve begun exploring burley-based blends–it’s like smoking a pipe again for the first time), and some quiet.

It’s been a crazy morning: the dog, less than twenty-four hours after being spayed, has returned to normal energy levels and is highly irritated about being stuck inside with an Elizabethan collar on. The Boy wanted to help, of course, but the difference now is that he’s able actually to help. He broke the dried bread into chunks for the dressing; he crushed crackers and mixed the liquid components for the casserole; he willingly taste-tested the pumpkin pie baklava; he kept an eye on everything. How did I listen to a story and talk to the Boy? Simple: his fits of helping merely punctuated his playing.

10:24

It’s always the same — Thanksgiving, Christmas, Easter, you spend all that time cooking and it’s over before you know it. Even when you slow down, even when you’re mindful, even when you want to stretch things out, you can’t.

You sit and listen to the Boy’s stories, plow through the food, and it’s done. Of course, when you compare the amount of prep to the time eating, even two hours would be “plowing through.” But you can’t complain: people aren’t eager to eat food that tastes mediocre at best, so I take it as a complement.

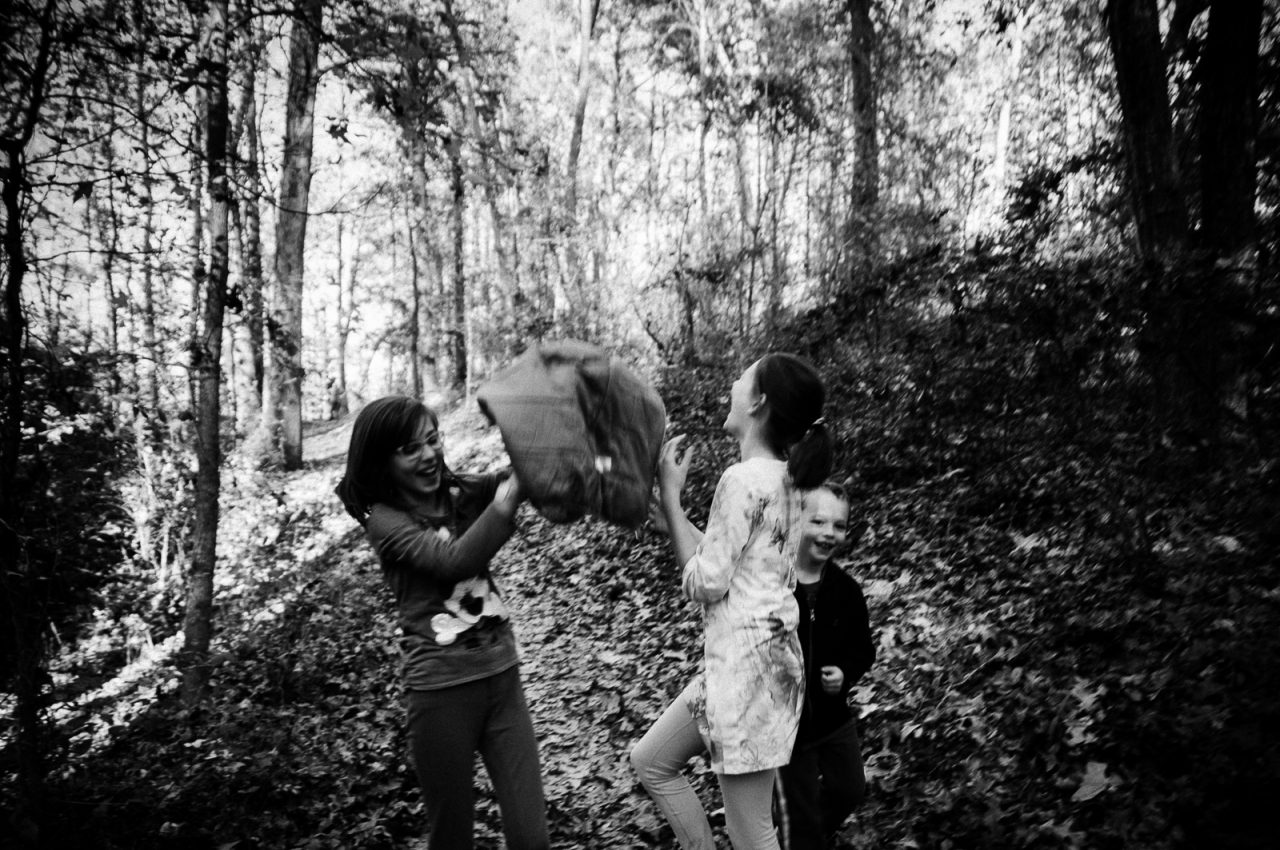

And go for a meandering walk afterward, the first quarter of it with the family. The rest head back because the poor dog, with her radar hat on, probably shouldn’t be out too long.

Pre-Thanksgiving

Immigrant Day

Helping

Sunday Evening

At a Loss

There are some times in my classroom that I am positively at a loss, that I am standing there, looking at what just happened, listening to what’s being said, watching what’s going on, and I find myself wondering, “What in the world do I do about this?” I’ve been in the classroom for almost twenty years now, and I’ve come to realize that I will always — always — have these moments.

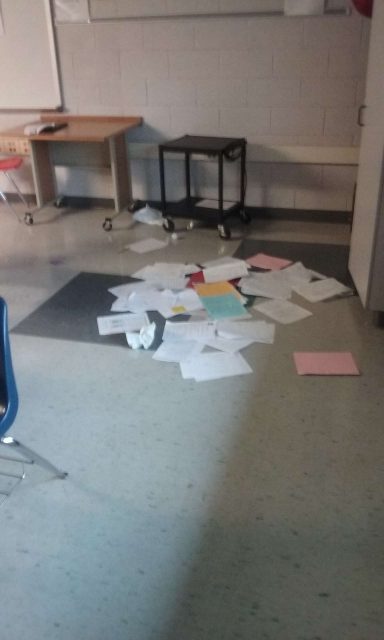

Last week, for example, in order to load a document I wanted the students to view on the projector, I turned my back on my most challenging class — challenging in that they are, by and large, not motivated and therefore not inclined to behave in a manner that produces the most efficient use of our limited class time — and in the few seconds that I had my back turned, this happened.

This, in fact, is a photo after I kicked some of the papers into a more consolidated pile.

Apparently, in a matter of seconds, a boy who sits in the back of the room stood up, ran to the front of the room, grabbed a girl’s binder, ran back to the back of the room, and emptied its contents on the floor with the girl in heated pursuit. This girl is not very popular, and she has a habit of antagonizing everyone around her and then playing the victim. In this case, though, she was the victim, but that didn’t stop the kids from hooting in approval at the boy’s actions.

I called them down; they stopped after a few seconds; and I didn’t have the slightest clue what to do. I removed them both from the classroom, but that’s hardly a preventative measure for the next time the kid gets an impulse to do something like this. Truth be told, the boy can be more antagonistic and disruptive among his peers as the girl.

These are thirteen-year-old kids. They’re not two or three. Yet their behavior belies their age, because this sort of thing happens so frequently. If it was a one-time occurrence, it would just be a question of youthful hi-jinks, but something similar happens on a regular basis, and I never really know what to do to prevent it.

Blowing Leaves

Book Character Day

Homework and Playing

Bedtime

“Daddy, will you come lie with me?”

The Boy is having trouble falling asleep, and when this happens, there’s only one real solution: to climb into the bed with him and let him fall asleep curled in one’s arms.

I’ll admit that there was a time that I was growing tired of this. It was an almost nightly ritual, and with so many things I needed and wanted to do in the evening once the kids were asleep, I just wanted him to drift off as quickly as possible.

But over the last couple of years, another change has happened, which has altered my outlook on stretching out with the Boy in the evening. The Girl, now almost eleven, requires little to no bedtime assistance, and some nights, I have simply kissed her goodnight and turned out her light. She’s growing up, and in doing so, she’s developing her own evening routines and rhythms, and unlike the Boy, she no longer gets scared as she’s going to bed.

It struck me, then, that E will be following suit soon. No, not really all that soon, but soon enough. A few years and the whole bedtime ritual in the house will look entirely different than it does now. A few more years and neither one will really want K or me to lie in the bed with them, stroking their hair, whispering to them to lie still and go to sleep. And I will look back on this time when I could have done it with a tinge of regret that I didn’t do it more often.

Which is why, when the Boy asked if I would lie down with him, I did so without hesitation.

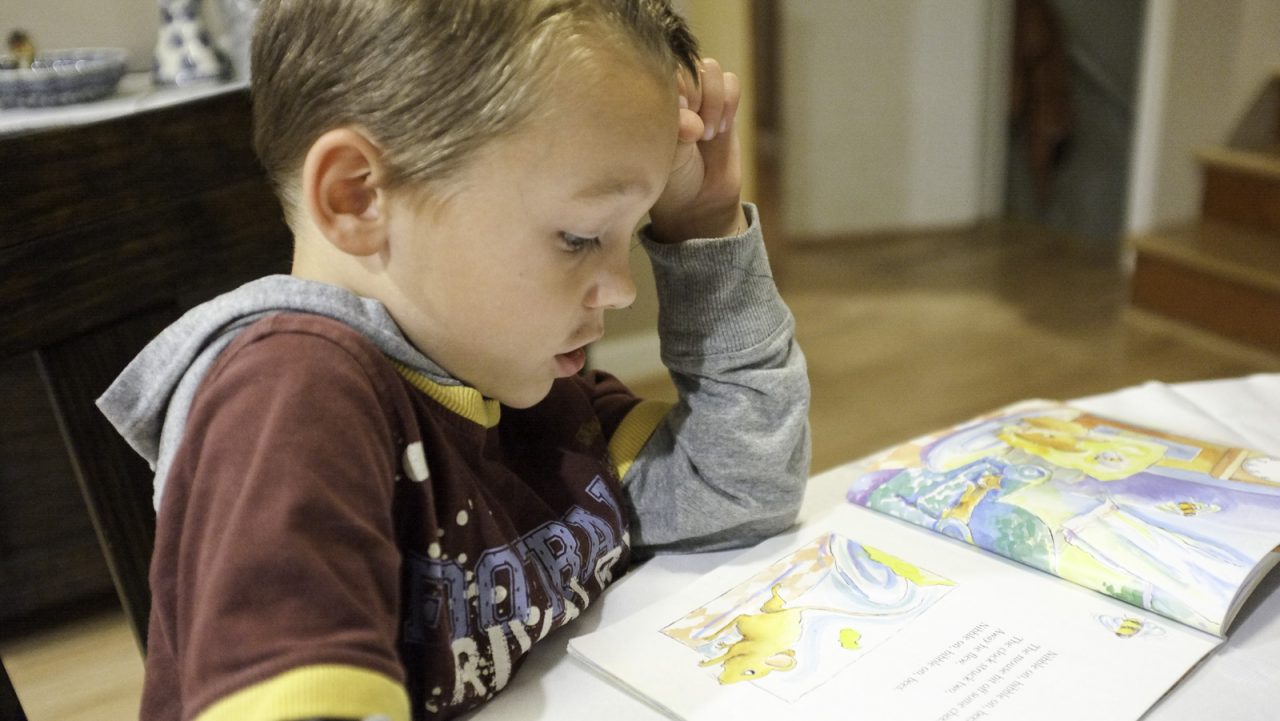

Lost Stars

E and I were lying on the bed in the master bedroom, reading. He always gets a book from school for his daily reading log, and often the book is leveled just right for reading with a parent: a few words he knows, enough short words that he can sound out, and a few words that he needs a lot of help with. Always a refrain of sorts, something easily remembered that he can just repeat.

Today’s book: My Dad and I.

We made it through the book, which was about all the things the narrator’s dad teaches him to do and all the things he teaches his dad to do, and E began teaching me about his star behavior system in school. Of course I knew all about it: I just had a conference with his teacher a few weeks ago, and we get a daily report about how many stars he ended the day with. But of course I let him explain it.

“We start with three stars, and if we do something wrong, we lose a star.” He paused, then added, “I haven’t lost a star yet this year.”

What will he do when he loses a star?

Updated B

The Girl got her report card today, and much to her surprise, she didn’t get that B. Turns out it was on the second quarter reporting period — which means she has a hole to dig herself out of. But at least the streak remains.

B

The Girl tomorrow will be getting the first B she’s ever made on a report card. It’s in social studies, and it weighs heavily on her.

“I got an A on the study guide,” she told me this evening, “but I got a C on the test.”

I don’t remember when I got my first B. Probably on my first report card. I can’t remember when I got my first C, but I think it was in junior high. I do remember getting the one D I ever received: earth science, ninth grade. I think I made all As and Bs in college, but if I had, I would have not graduated simply Cum Laude but rather Summa. Or so it seems to me.

Obviously grades were never all that important to me. Sure, I wanted to do well, but I didn’t beat myself up over it. I sat back and watched everyone who was interested battle for valedictorian and salutatorian honors, and I think I slipped into the top 10% of my class and was somewhat pleased with that.

The Girl’s biggest concern is remaining on the All A Honor Roll. Will this disqualify her for end of year honors? I had to admit that, despite being a teacher, I really didn’t know. Again, I never really worry too much about it.

My own students come to me sometimes worried about their grades. My English I Honors course has had the dubious distinction of being the first B for several students over the year. I express my regret, point out that I don’t give grades but that they earn grades, but in the back of my mind, I’m thinking, “It’s not such a big deal really.” For them it is: it’s a high school credit course, which means it will count toward their GPA.

I’ve had students’ parents have their children repeat English I in high school to get that A. I’ve even had one mother require her daughter repeat because her A wasn’t high enough. “Your class was much harder,” the girl wrote later in an email.

So I try to comfort L the best I can, suggesting that it’s not the end of the world. She dries her eyes and says, “I know.” But I know that doesn’t help all that much.