There’s been a lot of talk in conservative circles about Republican party allegiance, with three incidents in particularly coming into play: the three Republican senators who scuttled Trumpcare, Lindsey Graham’s comments about who should support him and who shouldn’t, and Bob Corker and Tim Scott’s criticism of Trump’s handling of the attack in Charlottesville.

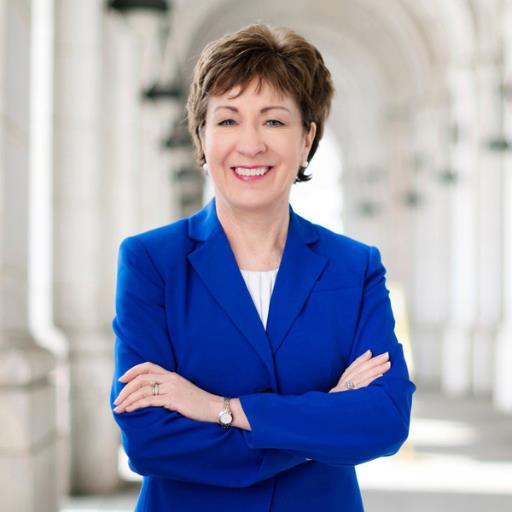

Most widely known, nationally anyway until Charlottesville, was Susan Collins’s, Lisa Murkowski’s and John McCain’s voting against the so-called skinny repeal bill that would roll back portions of Obamacare. They were ridiculed for their actions, called “Rinos” (Republican In Name Only), traitors, and worse. And yet why? Because they voted their conscience?

That’s exactly the action I want from my senators. I don’t want them to be mindlessly following some party platform and voting this way because it’s the establishment Republican way to vote. The same applies to Democrats.

I don’t vote Republican because I expect the office-holders always to vote Republican. I vote Republican because, by and large, many of the Republican positions resonate with my own positions. I’m more liberal on many social matters, though, and most of my views regarding education would still be considered left-leaning. But I vote Republican because that’s the way my conscience leans, and I would hope that Republican office-holders are the same.

However, the Republican party is not perfect, and I don’t expect it to be. And I expect office-holders to feel the same way. I don’t expect them to vote Republican for everything because everything Republican is far from perfect.

The alternative is simple: blind party allegiance. It means putting your thinking aside, putting your conscience aside, and going with whatever the party says. It is willfully surrendering your freedom to think for yourself. Blind party allegiance is unhealthy and dangerous: Blind party allegiance is the mentality of members of the Supreme Soviet and the Nazi party — our party is right no matter what! — and not of a well-functioning republic. I would add “like ours” to that last statement, but I don’t think it’s a particularly well-functioning republic right now.

Many of those who call the three Republicans who voted against the skinny repeal RINOs and such likely don’t even know why they voted that way. Collins explained it thus:

Many of those who call the three Republicans who voted against the skinny repeal RINOs and such likely don’t even know why they voted that way. Collins explained it thus:

In a statement after the final vote early Friday, Collins said that while she supported components of the final plan and that many Americans are suffering under Obamacare, she said Republican leaders punted on many difficult questions.

“We need to reconsider our approach,” she said. “The ACA is flawed and in portions of the country is near collapse. Rather than engaging in partisan exercises, Republicans and Democrats should work together to address these very serious problems.” (Source)

In other words, she was trying to make the process more republican (notice the lower-case “r”). She was, in my view, behaving like an adult who understands that we don’t always get everything we want, and that compromise and cooperation is always necessary. The other option is not democracy, but it does indeed begin with the same letter.

The second, less-well-known case is here in South Carolina, where Senator Lindsey Graham clarified his position on deporting DREAMers:

The second, less-well-known case is here in South Carolina, where Senator Lindsey Graham clarified his position on deporting DREAMers:

“I’m excited about giving you a chance to live the rest of your life” in America, Graham said of DREAMers.

“I embrace you, and I want you to succeed,” he said, speaking at a press conference with Sen. Richard Durbin (D-Ill.).

“To the people who object to this, I don’t want you to vote for me. Because, I cannot serve you well,” he said. (Source)

According to Fox News, this was “Senator Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.) [telling] voters who support deporting children covered under the DREAM Act that he didn’t want their vote.” It has the connotation, when framed like that, that Graham was saying, “Take your vote and shove it.” That’s the connotation I take from it. Yet look at how he himself framed it: “I don’t want you to vote for me, because I cannot serve you well.” He seems to be framing it in terms of talking frankly to voters: “If this is what you want, I’m not your best choice.” That seems to me highly ethical, surprisingly ethical for the stereotype of politicians misleading people to get votes. He could have said nothing and voted that way despite his earlier implications, by membership in the Republican party, that he would vote for laws that result in DREAMers getting deported and then vote differently. I admire the man for his frankness.

Some Republicans have suggested that this makes him a RINO, too, because he differs from the party line in this particular area. Some have even called him a traitor. For such Republicans, it’s the party line or nothing. Such politicians don’t have the right to call themselves Republican because these other Republicans disagree with their stance on one particular question.

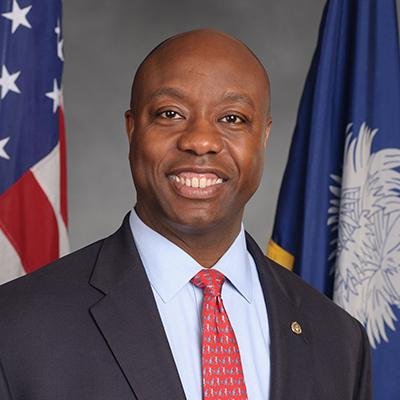

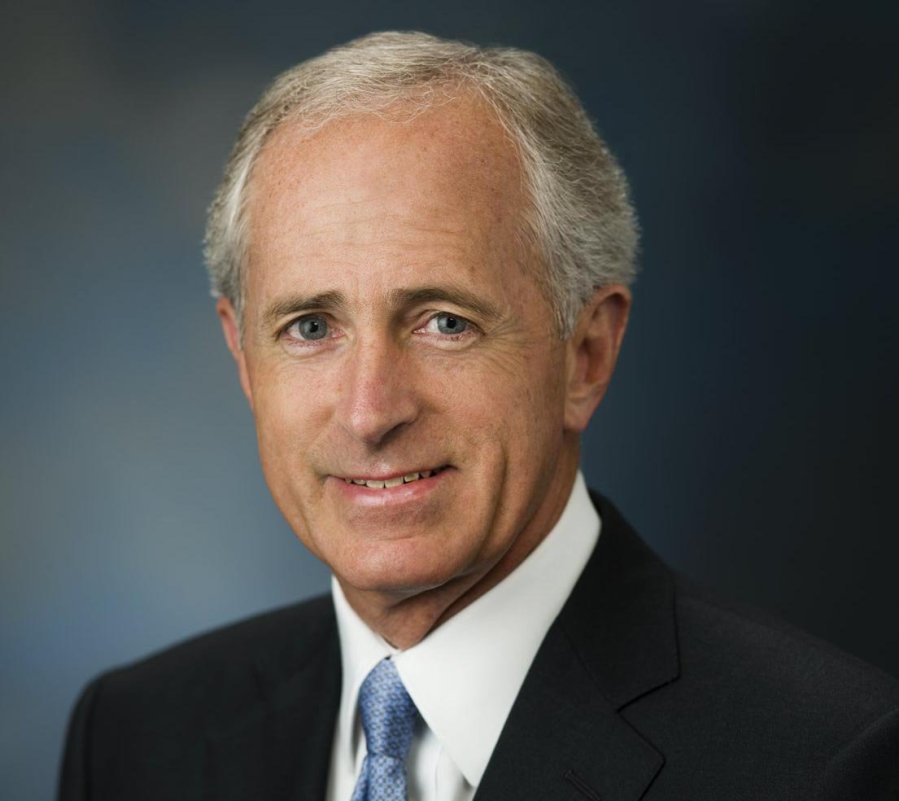

The final and most recent example comes with Republican criticism of Trump’s handling of the Charlottesville attack and his suggestion that the counter-protesters were as much to blame as the white nationalist protesters. Bob Corker and Tim Scott both criticized Trump for his response, with the former suggesting that it illustrated that Trump “has not yet been able to demonstrate the stability nor some of the competence that he needs to demonstrate in order to be successful” and the latter saying that Trump’s “comments on Tuesday started erasing the comments that were strong. What we want to see from our president is clarity and moral authority” (Source).

The final and most recent example comes with Republican criticism of Trump’s handling of the Charlottesville attack and his suggestion that the counter-protesters were as much to blame as the white nationalist protesters. Bob Corker and Tim Scott both criticized Trump for his response, with the former suggesting that it illustrated that Trump “has not yet been able to demonstrate the stability nor some of the competence that he needs to demonstrate in order to be successful” and the latter saying that Trump’s “comments on Tuesday started erasing the comments that were strong. What we want to see from our president is clarity and moral authority” (Source).

These two Republican senators criticized, in specific and pointed terms, the behavior of a sitting Republican president, an act which for some is unthinkable. Out came the claims of being a Republican in name only, of being traitorous.

One wonders for such Republicans who are so keen on labeling others in their party just what Trump would have to do to earn their criticism. Trump, during the primary season, suggested that he could go out on Fifth Avenue and shoot someone and not lose any followers. Perhaps for some, he’s right.

Increasing Partisanship

In 2015, Real Clear Politics published an article about such partisanship called “Political Partisanship: In Three Stunning Charts.” The first is most telling.

It shows that in 1949, Republicans and Democrats couldn’t really expect their party-elected officials to vote solidly according to party lines. They leaned left and leaned right, it seems, but didn’t always vote the party line.

There are a lot of potential explanations for this. In 1949, the world was still recovering from the Second World War, which was a time of relative political unity in the States. We were united in fighting the Nazis and Imperial Japan: war always heightens the “us” side of the us/them divide. But look more closely: even in a period of division, like the 1960s, there was more cross-party voting than today.

The Effect of Technology

When did it really start to split? Look at 1979 — that’s when two separate peaks are clearly visible with an ever-widening gulf between them. It grew in the 1980s, then exploded in the 1990s. It corresponds fairly well with the rise of cable and the growth of the internet. The net allows people to tune into information sources that confirm their pre-existing biases.

Pew Research did a survey about the “scale of ideological consistency” of viewers and their preferred information outlet:

Those who lean left can comfortably ignore opposing viewpoints if they wish; those who lean right can easily find a comparable echo chamber. Sites like left-leaning Daily Kos and right-leaning Breitbart promote hyper-partisanship: Commenters and writers alike regularly suggest that the other side is the other side because of stupidity and selfishness. People derogatorily call the other side “wingnuts” and “Demoncrats,” dehumanizing them and making it easier to discount the opposing view. These name-calling echo chambers we’ve created on the internet foster an us/them mentality that might be useful for defeating the Axis powers but are not particularly conducive to continuing an effective republic.

When you only hang around people with a right-leaning or left-leaning view that corresponds to your own, your idea of where “center” or “moderate” lie on the political spectrum gets skewed. The result is almost comical if the fate of our nation didn’t ultimately lie in the balance: Ask someone on the far left what a conservative newspaper is, and he might name the New York Times. Ask someone on the far right what a liberal newspaper is, and he’s likely to give the same response.

What’s even more troubling is the recent tendency, particularly in the right-wing camp, of assigning the dismissive label “fake news” to anything that disrupts their right-leaning bias. It allows the wholesale creation of “alternative facts,” as Kellyanne Conway labeled them, which might not be facts at all. In other words, this hyper-partisanship has descended to the level that people don’t even agree on what a fact is anymore.