Sunday started like it always does: Mass. We decided to Mass at a church run by Dominican monks. But this time, we had to figure out, once again, how to get there. Google advised us to take the metro again, this time one stop further to the north, and then a 900-meter walk. As we made our way closer to the church, it became more and more evident that we were nearing the Old Town — Stare Miasto.

A family Mass, it was called, and indeed, there were a lot of families there. Throughout the entire Mass, some child or other was fussing, crying, protesting. We felt right at home.

Well, almost.

Before Mass began, K was talking quietly with the L about our plans for the day — we’ll go here, see that, meet with these people, those people — when the woman in front of us turned around and asked K to be quiet. Throughout the entire church, children were fussing, crying, protesting, and it was complete chaos for a church, and yet she turned around to hush us. As if that made any difference at all.

So easily am I side-tracked from what’s really important some time that that little gesture sat like a splinter in my mind for some time, distracting me from the Mass, distracting me from so much that was going on around me. I felt slighted, personally insulted. And I’m sure K thought nothing of it.

Indeed, when the Mass reached the point in the Liturgy of the Eucharist that everyone turns to each other and says “Pokoj z toba,” she turned right around as if nothing had happened, gave the biggest smile, and wished us all peace. And I immediately felt an idiot.

After Mass, we met up again with J, M, and E for a stroll through the Old Town, which is as much a paradox in Poland as anything else. In short, it isn’t old. It dates from the fifties at its oldest areas, and the royal palace was finished only in the seventies. The reason, of course, was simple: the Nazis destroyed everything. Hitler commanded his retreating armies to raze Warsaw, resulting in 80-90% of the city being destroyed. The Nazis made a concerted effort to eradicate all traces of Warsaw’s cultural heritage, essentially wiping Warsaw from history. According to one article, it was

one of the most ambitious projects in human history was initiated. No one had ever attempted to reconstruct the monuments of a war-torn city on such a scale. The decision to do so was also in blatant contrast with the prevailing conservation doctrine of the times. After the war, when faced with rebuilding a town which had been virtually erased from the face of the earth, Germany, the UK, Holland, France and Italy reconstructed only selected individual historical buildings. The reconstruction of Warsaw followed exactly the opposite tactic. (Source)

But like everything, political motivations joined with other catalysts and the project got under way. (Click on pictures for larger view.)

When you walk around that reconstructed area, then, it’s hard to feel anything but admiration for Poles. It speaks to a stubborn clinging to culture, to roots, to history, that has helped the Polish nation survive, literally. After all, Poland for a period literally disappeared from the map, gobbled up by greedy empires to the east and the west. That the country even existed for the Nazis to attack was something of a miracle, and it should have been a warning to Hitler that Poles would not just roll over and give up. The reconstructed Old Town bears more evidence of that.

As we were walking, I explained all that to the Boy and the Girl. L was fascinated and saddened; the Boy just asked questions about the technical aspects of it. How, for example, was the royal palace blown up and destroyed completely? Did bombs send it up into the air? Did it crash down and break? How can we be walking through it if it was destroyed?

We spent a good bit of time in the royal palace, which seemed to me at first to be a bad idea. I didn’t think the kids would particularly like it, but as I often am when it comes to my own children, I was surprised. L, the artist, enjoyed looking at some of the paintings, especially the huge historical paintings of Jan Matejko.

His Rejtan, which pictured the First Partition of Poland, captured both our attention and seemed a good example of what’s possible for the Girl’s artistic creativity: Matejko, it seemed, wasn’t a stickler for historical accuracy, placing people in Rejtan that weren’t even in the area, let alone in the room, at the time. So pink unicorns with green spots and blue stripes are not really all that significant when it comes to lacking in “realism,” whatever that might be in art. (That’s not to say that the Girl paints pink unicorns with green spots and blue stripes. She’s more likely to paint Apollo these days. Still, she might, on a whim, put pink Speedos on him.)

Then there’s Matejko’s attention to detail. He researched his subjects meticulously. When he got a chance, he examined cloth from the era of the painting, and when it was available, armor from the time of the painting’s subjects.

By this time, though, both the kids (as well as J’s and M’s son E) were getting a bit tired. There’s only so much of “look but don’t you dare touch” that a five-year-old and a seven-year-old can hear. There’s only so many ridiculously ornate rooms (by our standards) one can look at before one gets a little overwhelmed by it all. So we walked to the banks of the Vistula, took a walk, and eventually made our way to a ferry crossing.

Along the way, a few sights completely unknown to Americans, like a group of priests and seminarians walking along in cassocks, sun glasses, and baseball caps.

Or men wearing the same sort of minimalistic swim trunks that I wore as a competitive swimmer twenty-five years or so ago — Speedos we called the no matter the manufacturer, and I always wore baggy shorts over top of them until the very last moment before the race. And here, they’re the standard swim suit.

Once we crossed the river, we met up with M’s brother, B, and head to M’s and B’s family home, where K and I were visiting many years ago when Leszek Miller, then-prime minister, signed the documents that made Poland a part of the European Union. Such lofty ideas were nowhere to be seen during this visit, though. It was all about the usual: family, life here versus life in the States, and the like. “Tell us, hour by hour, what does a typical day look for you guys in the States?” B asked at one point in the evening.

In the end, to no one’s surprise, we found very few significant differences. The cost of health care might be the only difference: we pay much more than they do. But that’s a different, more political conversation…

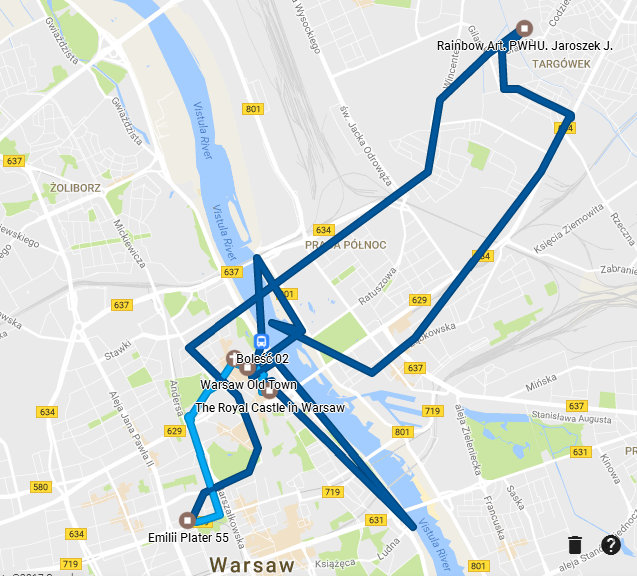

Today’s Travels

Not entirely accurate because Google is not entirely accurate, but generally speaking. (Of course we spent no time at “Rainbow Art, PWHU,” but that was the closest Google could find, and naturally I wouldn’t publish the actual address on the internet…)

More pictures at Flickr.

0 Comments