Back to the Store

Imitation

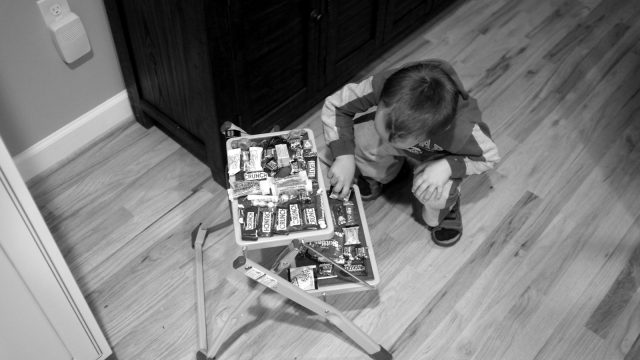

The Boy sees me do something, and he starts doing it. He sees K do it, and he starts doing it. He sees L doing it, and he starts doing it.

L has always enjoyed playing store, though in recent years, she really hasn’t taken the initiative to play it. When her Polish near-cousins come from the Asheville area, they might play school, and they might, just might, play store, but the oldest is now in middle school and such games seem pointless with just two.

She saw the Boy setting up his store after dinner and desert — a treat from the Halloween bucket — and she just had to play. And take over. And start directing the Boy. Playing with her can be so exhausting when she’s like that, and I often worry that she might be that way at school as well. She might not have the most friends possible as a result. And part of me wants to do something about that, to guide her a bit. And I have. But nothing has changed, so I’ve decided to take K’s advice and just let it be. It’s a lesson she’ll have to learn for herself.

Risks

Part of growing up is learning to take risks and learning not to take them. It all depends on the child, I guess. For us, it’s both: the Girl dives into almost everything without much thought of the consequences sometimes, and it’s something that’s always worried us; the Boy on the other hand watches, thinks, calculates, and sometimes — often — walks away from a given situation that he evaluates to be too risky. Between the two of them, the perfect mean.

Parenting is about risk as well. At the most basic level, there’s the risk of some kind of congenital defect in our children that provides them with challenges that might seem or simply be unfair, overwhelming, disheartening. Some folks are reluctant to have children for that reason. “What if our kid is born without certain wiring working and grows to be a sociopath?” is the extreme of this worrying. It’s never really been a worry of mine, though. It’s out of my control, so why worry about it.

That fear aside, we all want our kids to grow into these super-beings that fear nothing that needs not be feared, that boldly takes risks that matter, that stand up to bullies and make perfect grades. Of course all those things have differing priorities and can all be subsumed under the general idea of “well-rounded person” in the risk department. To that end, we teach, train, and so on. But there’s only so much as parents we can do about our kids’ personalities and outlooks on life. Nurture takes you only so far; nature gives some pretty strong dispositions.

The Boy, as a four-year-old, has certain risks that he decides to take that are appropriately sized. He’s begun to turn his back on his little Baby Bjorn potty and head straight for the toilet. He’s begun standing instead of always sitting. And that involves risks. Today he went upstairs to go to the restroom wearing one pair of pants and came back down wearing shorts. “I siu-siu‘ed on my pants,” he explained, using his typical Polish-English combination: a Polish base with the English past-tense inflection.

A few minutes later, he trotted back upstairs to clean up the mess, illustrating another parenting risk: lack of proper instruction on how to clean up potty messes leads to testing the absorbency of the bathroom rug.

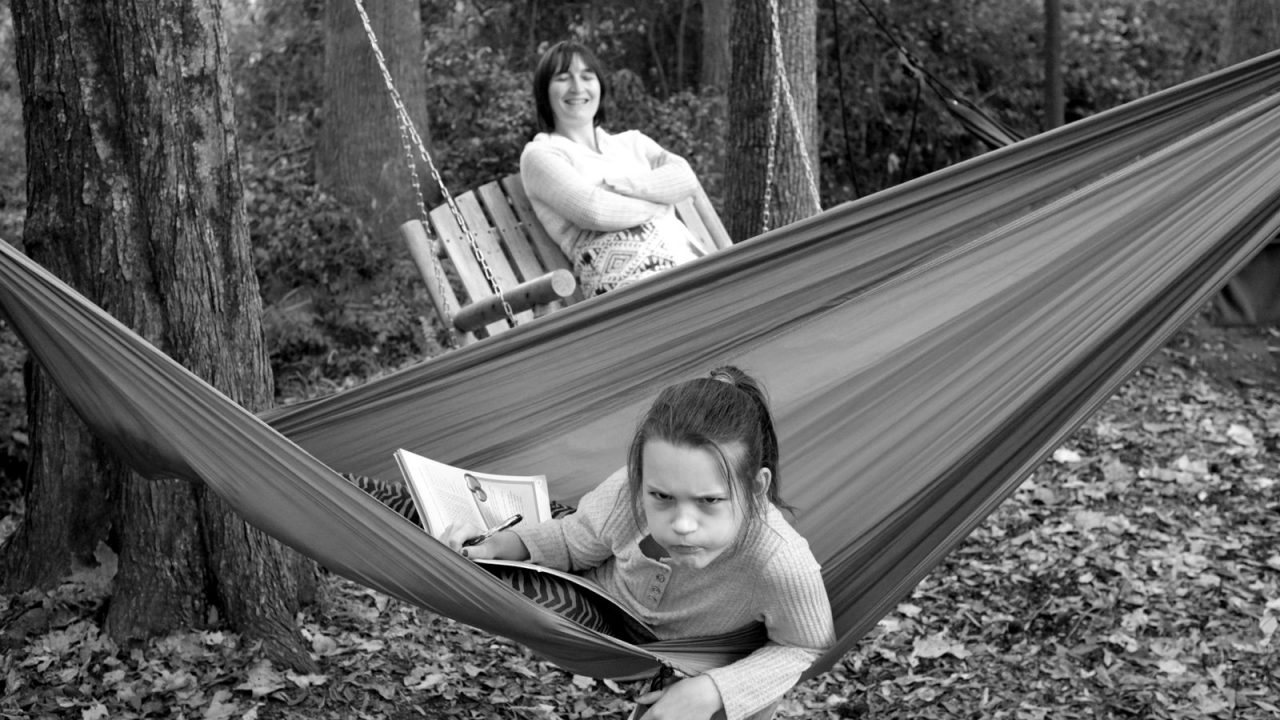

The Girl’s risk-taking is appropriately sized as well. She’ll swing like a maniac, but today she realized she was going a little too high and decided to stop pumping her legs. That kind of self-awareness has been a long time coming.

Still, she does things on our newest tree swing that make me just cringe. She likes to drop back and hang from her knees as she swings. She never does it when she’s swinging high, and she always holds on with both hands (unlike the picture below, taken before she actually started swinging). At some point, she’s going to decide that her gymnastics training, meager as it is, is sufficient to begin turning backflips out of the swing like the girl in elementary school who could do that, stopping students’ and teachers’ hearts alike. That will be a risk I don’t want her to take, but it’s a risk I’m also not sure she would take. As we approach her birthday — a little over two weeks to go — I know we’re edging ever closer to the risk-taking that makes all fathers nervous: love. Sure, it’s still a long way off, I tell myself, but those first stirrings will begin in the next couple of years or so, and she’ll begin offering her heart to boys. And we all know what that means.

Their risks are my risks, so for now I’m happy to face the little risks with the Boy and smile as the Girl pulls back a little from her ridiculously high arc.

Fresh Starts

All things come to an end, and more often than not, that end is itself a beginning. Our summer’s adventures in remodeling have finally come to a complete and total end. Well, almost — there are still pictures to hang on the walls, but we’re 99.97% finished now. And so as we prepared our yearbook, we finally took the time to unclutter the kitchen and take some “After” shots to complete our “Before” shots.

Our parish is in a similar situation: a two-year building project came to completion tonight with the dedication of our new Our Lady of the Rosary church. Like with our kitchen, there are still a few things the Father Dwight said we need to do, like completing an enclosure around the whole campus to ensure safety for the parish school — can never be too careful these days.

Father Dwight warned, so to speak, the parish that the liturgy for the dedication of a new church is long. “Really long,” he stressed. We dropped the Boy off at Nana’s and Papa’s as a result, because we really didn’t know what “really long” might mean. K comes from a country where most churches’ age is measured in centuries, and so the idea of attending a Mass to dedicate a new church was completely new to her. But Father did say “really long,” so we decided not to take a chance — the Boy can handle only so much sitting still.

“Really long” turned out to be just shy of three hours. Having grown up in a church were every week’s service was at least two hours long, I would say two hours and forty-five minutes make a long service, but not a really long service.

The liturgy was lovely, and it’s fitting that Fr. Dwight be the pastor of the parish: it’s a uniquely Catholic-looking structure, and Fr. Dwight is a uniquely un-common Catholic priest. Raised a Protestant, he converted to Anglicanism and moved to England where he married, started a family, and had a lovely parish. Then trouble struck, so to speak, and he and his family converted to Catholicism, which meant the loss of his vocation. Or so it would seem. It turns out, several dozen married Anglican priests have converted to Catholicism and then been re-ordained as Catholic priests with the discipline of celibacy being waived for them. So he posed with the bishop and his wife and four children after Mass, making it an odd sight in an oddly traditional church.

The real stars of the evening, though, were the members of the choir, including L. She’s been singing in the children’s choir for several months now, and she spent more time in the church today than she’d spent in a month of Masses — over five hours.

The results, though, were stunning. A Catholic church that looked, smelled, and sounded like a Catholic church.

During the entire liturgy, I smiled occasionally as I thought, “This is not just some lovely church we’re visiting while passing through here or there. This is where we will go to Mass every Sunday now.”

Four Changes

One

“You always use that one.” The Girl was downstairs as K worked on our yearly photo calendar and putting finishing touches on the yearbook I create and she polishes (which is not to say she was Polishing it — it remains untranslated this year). Since I was upstairs, I really don’t know what the conversation concerned other than the selection of this or that picture. It occurred to me that she is becoming a vocal and thoughtful member of our family cognitively. Her tastes and her views are no longer merely childish, and entertaining them is no longer simply a matter of being a good and patient parent that encourages a child by simply listening to her. We’ve been through that; we’re going through that with E. Now, she has her own opinions that are not based entirely on childhood fancy.

For instance, she selected the granite that completes our kitchen. It wasn’t just a matter of, “Ooh, this is pink and pretty!” like she might have as a younger child. (The granite is not pink of course.) It was a thoughtful choice that, as I recall, she made with K as they held the sample of the cabinets we’d chosen.

Two

This afternoon I caught a glimpse of another kind of change. We took the kids to see Disney on Ice after lunch, and it was the second time for L. The first time, she was so into Disney and princesses and pink and blue. She sat in rapt attention, almost in awe. There was Peter Pan and the Simba and everyone else she’d watched at Nana’s and Papa’s. Today, the show ended with the inevitable: a long-ish re-telling of Frozen. A couple of years ago, she was obsessed with that, with that music. She marched around Fort Pulaski singing that song, performing it for any passers-by who took the time to stand and watch — and a few did. As the song approached, I was curious what she might do. “Here it comes!” I whispered as Elsa retreated to her winter hideaway. “Here it comes!” And she smiled at me. A polite smile. The song began. I looked over at her again. “Aren’t you going to sing along?” The same polite smile, head cocked a little bit, as if to say, “Daddy, do you think I’m so childish or something?” The thing is, she can still be surprisingly childish, but at that moment, she was fourteen or more.

The Boy’s take on Disney this afternoon can be summed up in three things he said:

- “I just don’t like pretty things.”

- “I like vehicles. There were no vehicles.”

- [Spreading his arms out as far as they could go] “Disney on ice was this long.”

Three

As I’ve spent the last several evenings putting together our annual yearbook, pulling pictures from our photo collection and occasionally taking a bit of text from here — every year, it’s the same: I swear I’m going to make it as the year goes along and then never even begin re-gathering the pictures (and I say re-gathering because I reuse many from here) until late October — I had a conversation with K in whispers as the kids were up having their baths.

“Do you realize that almost all the pictures from this year seem to be of E?”

She nodded in sympathetic agreement. “Well, he is the youngest.” But it just seemed like some kind of favoritism. We agreed that she’d actually been kind of avoiding pictures, not showing the least bit of excitement when the camera came out, even frowning at it occasionally. Foreshadowing the soon-coming day that she actually chides me for putting pictures on the internet. “My friends might find that picture!”

Four

Before the show, we made the requisite restroom stops, and I stood outside the ladies’ room to the side waiting for them. (The Boy still occasionally chooses to go with K — only a little longer before that’s really no longer appropriate. But that’s a different story.) L was the first to emerge, and for a moment, she didn’t see me and merely walked toward my general location. There was a little bounce in her step that made her gait appear a little older, and her hair was lying on her shoulders in that casual way that older girls probably only dream of getting their hair to do — slightly unplanned, slightly messy (perhaps pouting might be the better term), yet certainly not unkempt, just casual — I could see her at fourteen, at fifteen, at twenty.

Thanksgiving 2016

In the morning, it’s cooking. And the Boy wants to help. He wants so much to be a big boy, to do the things he sees adults do, to do the things he sees me do. It’s humbling to think that I am for him the example of what a man is supposed to be.

After a few hours of work, we head to the backyard, where the leaves make a kaleidoscopic carpet and curtains. One advantage of things not being as wet as they often are — there are colors. The last few years, it’s seemed like it rained a lot during autumn and all the leaves just turned black and fell off. This year, there’s no chance of that happening. Sure, we’re eleven inches behind in rainfall now. But those colors.

Mid-afternoon, it’s back to the kitchen to finish up everything. This goes into the oven, that comes out. The turkey remains the whole time. K’s a bit nervous about the turkey: we haven’t done a turkey. Ever. It’s not “We haven’t done a turkey like this” or “We haven’t done a turkey in this gas oven” — we just have never baked a whole turkey. Nana and Papa always contributed that to the Thanksgiving dinner. Still, how hard can it be? Research a few recipes, double-check the temperature and time in relation to the weight, then wait.

In the end, everything turns out fine.

Better than fine.

Everyone goes home, K goes to bed early, and I head downstairs for an after-dinner drink and cigar. I scroll through what’s new on Netflix and see one of my all-time favorite movies is now streaming: Oh Brother, Where Art Thou?

How can I resist?

Preparation

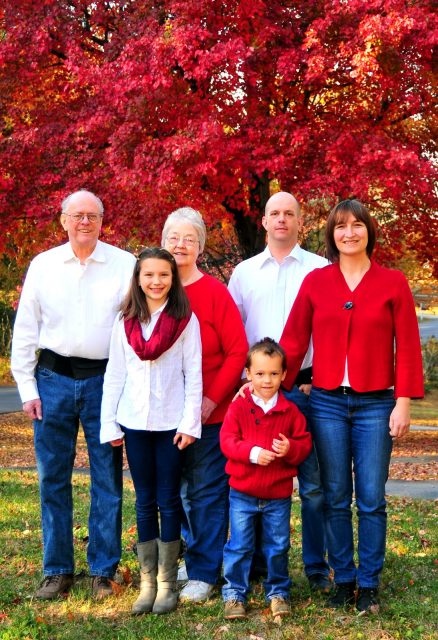

Portraits 2016

Preparing for Portraits

Energy

Swing and Dinner

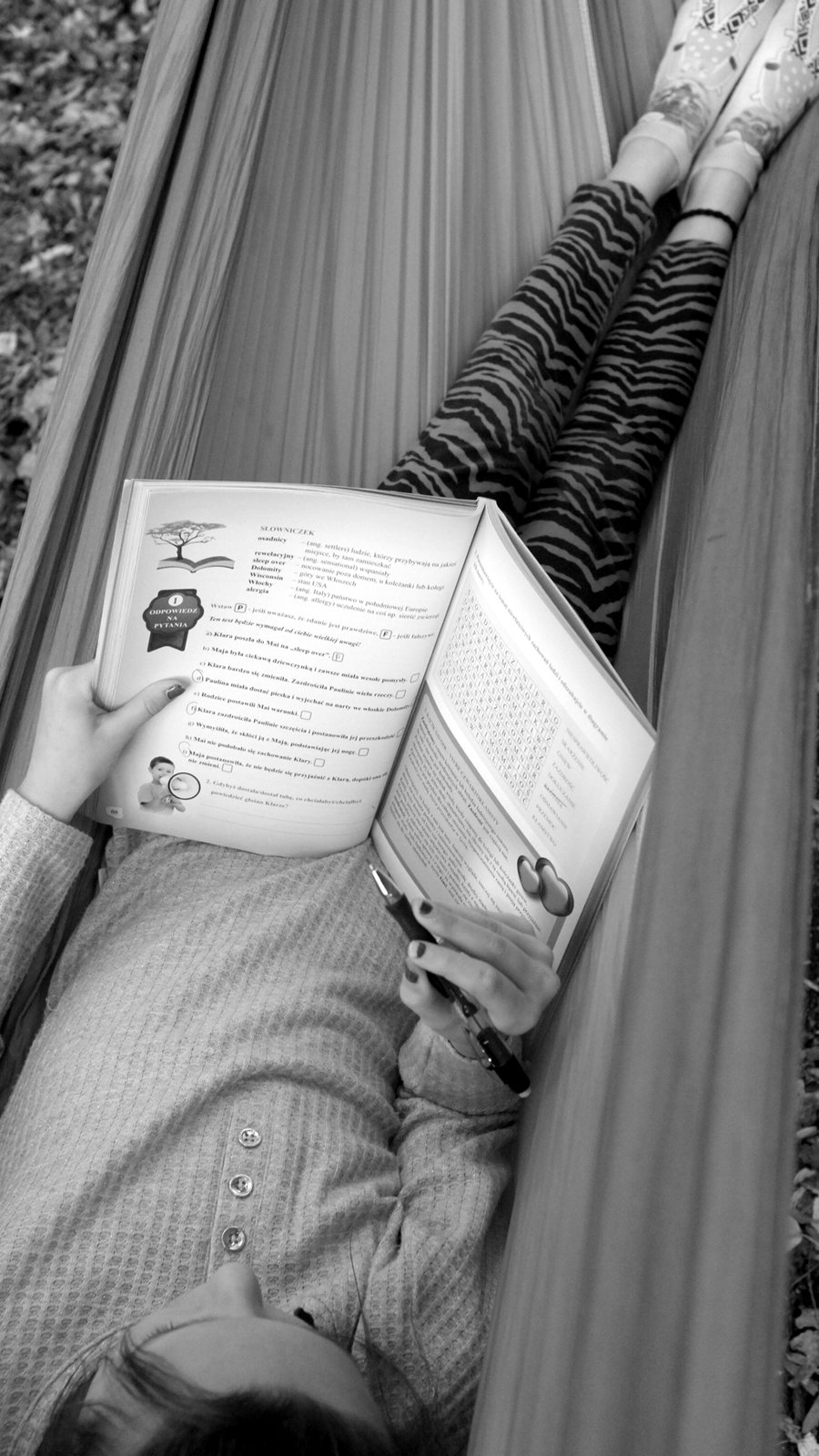

Curriculum

Three events today, happening within moments of each other, reminded me just what challenges some students in my class face, and how I am often really not teaching what I thought I would be teaching to thirteen-year-olds.

We’re working on a cross-curricular unit that incorporates Sean Covey’s Seven Habits of Highly Effective Teens as the anchor text. Since I’m the literature/reading teacher, the unit starts in my room. To make the process simpler and faster, as well as to hit more standards, I’ve designed a unit that includes a jigsaw reading of the article: independent groups read one chapter of the book, then present their chapter to others who read other portions of the book. Each group gets a habit.

I copied the book to make my life easier: we don’t have enough books for two classes to use them simultaneously, and because I have a class-set of Chromebooks due to an elective I teach, I told the other English teacher that I could just scan the book in for my students. I scanned them in two pages at a time, which meant that, because the first page of each chapter was on the right side of the page, there was always a page from the previous chapter as the first page. I knew it might be confusing for some, but I thought that most thirteen-year-olds could figure out that it must be part of the previous chapter, especially since I’d already shown the kids how to read the PDF versions of the novel: Left page, right page, scroll down; left page, right page, scroll down. When I found that some students were having trouble with that and were in fact treating the first page visible as the first page of their chapter, I was frustrated, disheartened even.

Later, as I was moving around the room, I noticed some students having problems with Google Docs’ outline feature. It turned out that, instead of turning on the automatic-numbering outline feature, they were manually adding numbers — like it was just a typewriter instead of a computer. Since I had showed the students how to do this, since we had spent time working as a class, working as groups, working even as individuals with simple outlines, I thought everyone knew how to do it But if a student is not paying attention, if a student is more interested in most everything else other than what is being taught, it shouldn’t come as a surprise. Yet it happens to these students time and time again, and they can never figure out why. What are the chances of someone who can’t pay enough attention to learn how to use a simple outline feature ever going to keep a job? Perhaps these students will learn some focus, but they’ve made it this far without paying attention: what’s in it for them to start now?

Finally, I had a vivid reminder of how poorly some of the students read. A student was struggling to figure out what to put as a sub-point in his outline. To his credit, he had figured out that the heading immediately above would be a main point and knew that something below it must be the sub-point. The first paragraph after the heading was short:

“Synergy doesn’t just happen. It’s a process. You have to get there. And the foundation of getting there is this: Learn to celebrate differences.”

I sat down by the student and quickly assessed the problem. “Read the first paragraph under the heading,” I said. He read it. “Tell me something about ‘synergy’ from the paragraph.” “It’s a process,” he said after a moment’s hesitation. At this point, I was thinking that another helpful question or two and I’d be on my way. “And what is the foundation of that process?” He made a wild stab — something completely outside the text. “No,” I reminded him, “no, it must be in the text. It’s right there in the text.” Another wild stab. “Find the word ‘foundation’ in the text,” I instructed, growing a bit frustrated with my ineffectiveness. He found it. “And what does it say is the foundation? What’s right after it?” Another wild guess. I sat there, wondering what was going on in his head, wondering if he was seeing, what he was thinking, what even he was feeling.

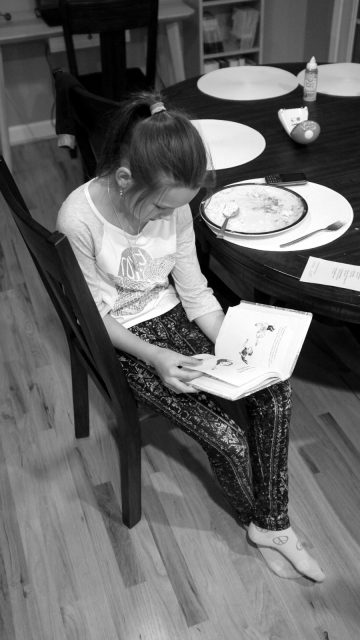

This evening, I called the Girl to the computer and had her read the paragraph. “What is the foundation of synergy?” I asked. “It’s a process. You have to get there,” she began. “No,” I redirected, “one thing. It’s in the text.” She re-read, then said, “Learn to celebrate differences.”

I don’t say this to brag about our daughter. I point this out to show the level of reading of so many of my students, students who should have responded like L, for she is, according to testing, reading at about an eighth-grade level. The level my students should be reading at. What’s most frustrating about all of this is the shortsightedness of these same students. They don’t see how far behind they are — and how could then? They divide school into two, fatalistic groups: the smart kids classes and our classes.

Add to this all the students lacking social skills who need instruction in this simply to reach a state of mind in which they can functionally work with someone. No, that’s not even correct — to get them to the point that they can stand to be in the same group as someone they find irritating. Several students in my lowest level class are incapable of getting along with much of anyone. “He annoys me.” “She gets on my nerves.” “He’s a pain.” “We might fight.” So on top of basic reading, I have to try to teach them how to deal with each other. Given their fatalistic worldview, that’s nearly impossible. “When I’m mad, I just react. It’s just how I am.” For them, it’s as immutable a fact as the inevitability of tomorrow’s sunrise. There is nothing they can do to stop it. Is this laziness? Learned victimhood? Personality? Nature? Nurture? All the above?

It’s not that I’m feeling pessimistic about my chosen profession. I’m just not sure those who don’t teach, who don’t interact with such kids on a daily basis, really know the extent of the problem we face in the American education system today, and all too often, those very people are the ones making the decisions, about funding, about testing.

Comfort

The Boy and I were playing just before bedtime. The miasteczko that T and he made during their visit this weekend is still up, so we decided to make use of it. As often happens when playing, the Boy decided to pontificate a bit. Picking up a convertible, he began explaining, “This is a big car. It can hold a lot. I think maybe 38 gallons.” He handed me the car upside down and asked me to read what kind of car it was.

“It’s a 38 Gallon Cruiser,” I said. He beamed.

“I said that!”

I was expecting such a response, hoping for it at the very least. I like when something I say, something K does, something L makes him, gives him a certain kind of comfortable joy. It was the same with L when she was his age, still working out how everything worked, still not quite sure she had a handle on some of the basics. Of course, I look at her now and think, “You still don’t have a handle on some of the basics,” and I look in the mirror shaving and think, “You still don’t have a handle on some of the basics.”

K has a handle on the basics though. She knows what brings a smile to everyone’s face: homemade rosół. The Boy leaves his bowl empty; the Girl goes back for seconds; even the older cat is happy to get the dregs in E’s bowl.

The basics.

Monday Chills

Rainy Sunday

“We can’t stay for choir practice because we have family visiting,” K explained to the choir director this morning after Mass. As the dedication of the new church is only weeks away now, after-Mass choir practice has really ramped up. But today, we decided L could miss it. Because of family.

Of course, M and her daughters are not related to us in any other sense beyond her being E’s godmother and sharing the same adventure as K of being a Pole in America. But they’re still family. We spend holidays together; we know (or rather, K and M know) rather intimate details about each others’ lives; we’ve shared the same struggles at times.

You choose your friends; you don’t choose your family. It’s a truism that gets both sides of the equation right and wrong: because you don’t choose your family, it can be more difficult to love them and more important. (Note: such is not the case here.) Because you choose your friends, the relationships are more valuable and more fragile. That’s why close friends and family blurry the lines: these relationships have both elements.

So time with this kind of family is precious: E gains two more sisters for a weekend, and L gains siblings more her age. And because they’re more like family than friends, there’s no compunction in telling L that she’s being a pain in the back side (which she can be) or telling E that he’s got to share his new siblings (which is is reluctant to do).

Fall Saturday

Today was one of those days that suggests that fall might finally be here. I wore long sleeves all day, and in the evening, when outside, I was just a bit chilly.

We wake up with K heading off to work for the morning and us staying behind. I spend some time in the morning working on some side projects and the kids entertain themselves. It’s a good thing, a good skill, to be able to pass a lazy morning without turning on the television.

Mid-morning, I come up, and we get to cleaning. I do the vacuuming while the Boy sorts silverware from the dishwasher, the Girl uses our lovely Shark cleaner to wet-clean the hardwood

When K gets home, she and the Boy get to baking. The Girl is upset that the Boy has horned in on the action. It’s one of those times that K just lets her be.

Evening, friends that are almost family arrive for a short weekend visit. E’s favorite near-cousin sits with him and makes a miasteczko.

Soup with Papa

The best way to get the kids to eat certain foods is to hide them. No, that’s not quite right. E will try just about anything. He might not like it (as when he commented that a butternut squash soup tasted more like “sea turtle soup”), but he’ll try it. No, it’s just L that we have to deceive. So K puts a lot of onion in a lot of soup, but it’s always turned to a paste that simply adds flavor and thickens the soup. Tonight’s soup: pea soup.

“What kind of soup is this?” she asked.

“Do you like it?”

“Yes.”

“Then you don’t want to know.”

American Tune

Four years ago, I marveled at how some of these lines mirrored what I was feeling after a disappointing election. I still feel this way after the election in 2016, but for different reasons.

With an untried, inexperienced, president-elect of questionable integrity, surely these are, in many ways, America’s most uncertain hours, both for Republicans and Democrats.

Decision, Redux

The Girl is tough. I don’t mean that she’s resilient, that she can take a metaphorical beating and get up from it. I mean she’s stubborn, so very set in her ways that she looks at me sometimes with a glint in her eye when she’s resisting and I think that if we could just get that stubbornness off of petty things, get it away from food and her obstinate refusal to try anything new, get it away from her irritation with the Boy and her stubborn insistence that everything go her way, get it away from her frustration with little failures and her insistence that the original solution to the problem (the solution that is obviously anything but) is the only solution to the problem — if we could just redirect it, steer it just a bit, give it just the slightest nudge, she would have the resilience of a diamond.

Last night, we sat the table, fighting about food. I insisted that she eat some of the veggies that went alone with the stir fry we had for dinner. I insisted. I insisted. I insisted. And she fought. “I won’t” became “I can’t” became tears of frustration and anger.

I sat thinking whether it was necessary. Am I ruining her culinary tastes, creating a stubbornness for life, by doing this? Is it really a big deal that she doesn’t eat something? Am I making something of nothing?

And then there was the question of disobedience. I can’t have that — it’s pathological. I get it enough from students at school. And yet, who really wants to submit?

And then there was the question of resilience: if I let her get by with not tackling this meager challenge — in the end, it turned out to be five, five bites — what kind of a child am I raising? I want someone who will slay dragons, and she can’t even eat five damn bites of vegetables.

The other day in school, I had a quiet conversation with a very bright young lady who wanted to leave my class because she was so frustrated. She wasn’t frustrated with me, or with my class, or with anyone in the class. But someone had said something, and she was on the warpath. She was ready to swing, as she said.

“But you don’t have to. You can control that.”

“No, I can’t,” she replied. Her tone wasn’t argumentative or plaintive — it was matter-of-fact. “I can’t.”

Of course she can, and I told her that, but to someone who has such a very fatalistic worldview, suggesting that she can control something she’s always been convinced she can’t control was like me suggesting that she could control her digestive system like those tabloid gurus who the tabloid writers excitedly proclaim haven’t had a bowel movement in decades. It makes sense: if you can control your heart rate and breathing, why can’t you control every aspect of your body, including bowel movements and aging. Yet on a practical level, it’s ridiculous to me. That’s likely how this young lady viewed my suggestion that she could simply not fight, that she could unclinch her fists, take a deep breath, and let people say whatever the hell they want to about her.

I don’t think the Girl will ever become anything like that. But perhaps I’m so concerned that she might, even with the little things, that I worry I overreact.

“Tomorrow,” I decided, “I must make better decisions.”

The Democratic party, now, seems to me to be a little like the Girl. It stuck by principles that seemed so important at the time, but in the end, one principle in particular cost them dearly. The principle? That as progressives, they are on the “right side of history,” and to be on the right side of history means to be the party that has the first black president, and what could put them more firmly on the right side of history than to elect the first woman president. And so the party put forward a candidate that was seen by Republicans and many Democrats alike as untrustworthy.

In her hubris, Clinton assumed she would be the Democratic nominee, because that would put the Democrats once again on the “right side of history.” Sanders was not supposed to fight. Sanders was supposed to be on the “right side of history” as well. He got in the way, but the email leak scandal shows that the Democratic party machinery conspired to make sure he got put in his place, white male that he is. When the general election cycle began, Clinton, as the freshly minted historic nominee, knew she and her party were on the “right side of history,” and given Trump’s ridiculous and offensive behavior, it almost seemed poetic that he was the candidate, the perfect ying for her yang. Slate, an openly left-leaning magazine, can finish the argument better than I:

The party establishment made a grievous mistake rallying around Hillary Clinton. It wasn’t just a lack of recent political seasoning. She was a bad candidate, with no message beyond heckling the opposite sideline. She was a total misfit for both the politics of 2016 and the energy of the Democratic Party as currently constituted. She could not escape her baggage, and she must own that failure herself.

Theoretically smart people in the Democratic Party should have known that. And yet they worked giddily to clear the field for her. Every power-hungry young Democrat fresh out of law school, every rising lawmaker, every old friend of the Clintons wanted a piece of the action. This was their ride up the power chain. The whole edifice was hollow, built atop the same unearned sense of inevitability that surrounded Clinton in 2008, and it collapsed, just as it collapsed in 2008, only a little later in the calendar. The voters of the party got taken for a ride by the people who controlled it, the ones who promised they had everything figured out and sneeringly dismissed anyone who suggested otherwise. They promised that Hillary Clinton had a lock on the Electoral College. These people didn’t know what they were talking about, and too many of us in the media thought they did. (Slate)

There are other things at work there, I realize. And this all says nothing about what the political right accomplished in this election. National Review sums that up well:

This is a direct rebuke to progressive hubris. It turns out that the progressive elite’s preoccupations with identity politics, social shaming, and radical sexual change don’t motivate their “coalition of the ascendant.” In the past eight years, the progressive movement has doubled down its attacks on churches and in recent years directly confronted American law enforcement. It has attacked free speech, the free exercise of religion, and gun rights — secure in the belief that history was, as they put it, on their “side.”

The result was clear: The Democratic party lost ground with America’s poorest voters. Citizens making less than $50,000 per year propelled Obama to victory over Romney. Exit polling shows that Trump improved the GOP showing by 16 points with voters making less than $30,000 per year and by six points with voters making between $30,000 and $50,000, which more than offset Democrat gains with the middle class. (National Review)

For the right, this was not about choosing a man over a woman; it was about choosing one ideology over another. The New Republic recognized this as well:

This brings us to the problem of how the Democratic Party—and America as a whole—can recover from this calamity. There is sure to be a civil war among Democrats, with leftists arguing that a purer, less compromised version of liberalism will have a better chance of appealing to those very voters who put Trump over the top. There will be a push to expand the Democratic message beyond the identity politics that has increasingly defined the party in recent years—to welcome with open arms those blue-collar and middle-class whites who have been culturally alienated by newly assertive blue-collar and middle-class workers of brown skin. And there will be a backlash to this, an argument that the Democratic Party’s function is to redress the wrongs that have been done to minorities and make white America atone for its sins—“to force our brothers to see themselves as they are,” as James Baldwin put it, “to cease fleeing from reality and begin to change it.” (New Republic)

In that vein, some liberals suggest that this is just a sign of the latent misogyny and racism in America, but that kind of talk seems to indicate that they haven’t yet learned much from this earthquake. What should they talk away from it? Back to the National Review:

The presidential candidate that voters believe less, like less, and think less qualified won the election. In other words, rather than endure four more years of elite progressive rule, the American people chose to gamble on a reality-television star with well-known and openly notorious character flaws. That’s how much they were ready for change.

It was all about change, Trump supporters say.

In that sense, though, Trump’s supporters are a little like the Girl as well. The Girl tends to see every setback as a complete disaster. So many little things blow up into the end of the world for her. The veggies were an impossible task. We’d asked her to do the impossible, and she just couldn’t do it, couldn’t imagine it. In the same way, many on the right saw the election of Clinton as the end of the country. Obama began the transformation into a socialist republic, they saw, and Clinton would finish it.

Change can be good. It can be scary. These are merely truisms. Yet, change often does work, and so tonight, I changed tactics with the Girl: I put her veggies on a plate and told her that she needed to scarf them down before the Boy, who was napping, and napping hard, woke up. “Then for dinner, all you’ll have is chicken and rice.” She jumped at the chance. A little reframing, a little rewording, and we got reached the same conclusion.

Eventually, the left will realize this and act on it. Frustrated Americans will vote the right out and the left in, until the cycle repeats again.