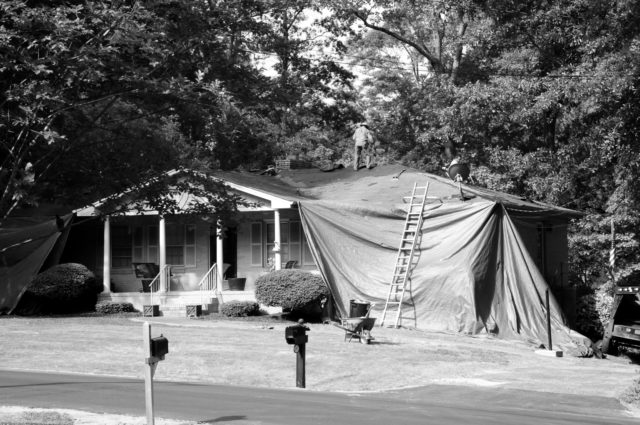

They were already at work when I peeked out the front windows at eight this morning.

Our neighbors finalized the purchase of their home, and in doing so, got enough money from the bank to fix up a few things, including the roof. And so while the Boy and I worked on trimming the hedges in the front — well, while I worked on it and he helped, which, as is often (but not always) the case, makes more work for me — we heard the sounds of scraping and popping as the workers pulled up the old roof, accompanied occasionally by some song or another that the workers would sing. I wouldn’t recognize the songs; they were in Spanish.

I thought about the situation for a few moments and realized that had this been in the suburbs of Chicago, it might have been Polish a few years ago. It still might be, but the likelihood is smaller: with the opening of the EU to Poles some ten years ago, few people come here to work. It’s easier just to work in Austria.

At any rate, by the time we finished the hedges, they had pulled all the shingles and tar paper off. And it was then that the unlikely happened: rain. It hasn’t rained in a couple of weeks, but the roofers had no sooner gotten the first bit of tar paper down than it started raining.

The Boy and I by that time were working on improving the draining at the bottom of our driveway, and so we decided just to continue working.

I dumped the gravel; the Boy threw away the empty bags. One of the few but increasingly frequent times when his “I want to help!” was actually help.

“Teamwork!” he exclaimed. Indeed.