Cooking

Snow Day 2016, Part 2

Another day off school, another typical Greenville County Schools snow day — not a bit of snow visible in our part of the county, but apparently enough snow in the north portions of the county to render things unsafe. And so we kept ourselves occupied today in a variety of ways — details when you mouse-over.

Two Conversations

One

Mama, why does Daddy have bronchitis?

I don’t know.

Is he going to die?

No, honey.

Two

Daddy, hear that? (Slightly congested cough.)

Yes. Are you okay?

We were out for that spacer [walk] yesterday, and there was cold air, and I had it in my mouth, and I swallowed it.

Did you get some medicine?

Yes, Mama posmarować-ed [smeared] me with special olej [oil]. I’ll be okay in a few minutes.

Garbage-Bagging

“It’s supposed to start around seven this evening,” I explained. “That’s what all the meteorological reports suggest.” The slight bit of icy snow that frosted the ground yesterday was not enough to do much of anything, one would think, but when you’re on the South, any amount of “snow” is significant for children. So the suggestion that we might have even more snow was the stuff of sweet dreams as the kids plodded off to bed. “Is it snow?” was the mantra of the evening, but they went to sleep with complete confidence with the weather reports, knowing that they were only off by the time.

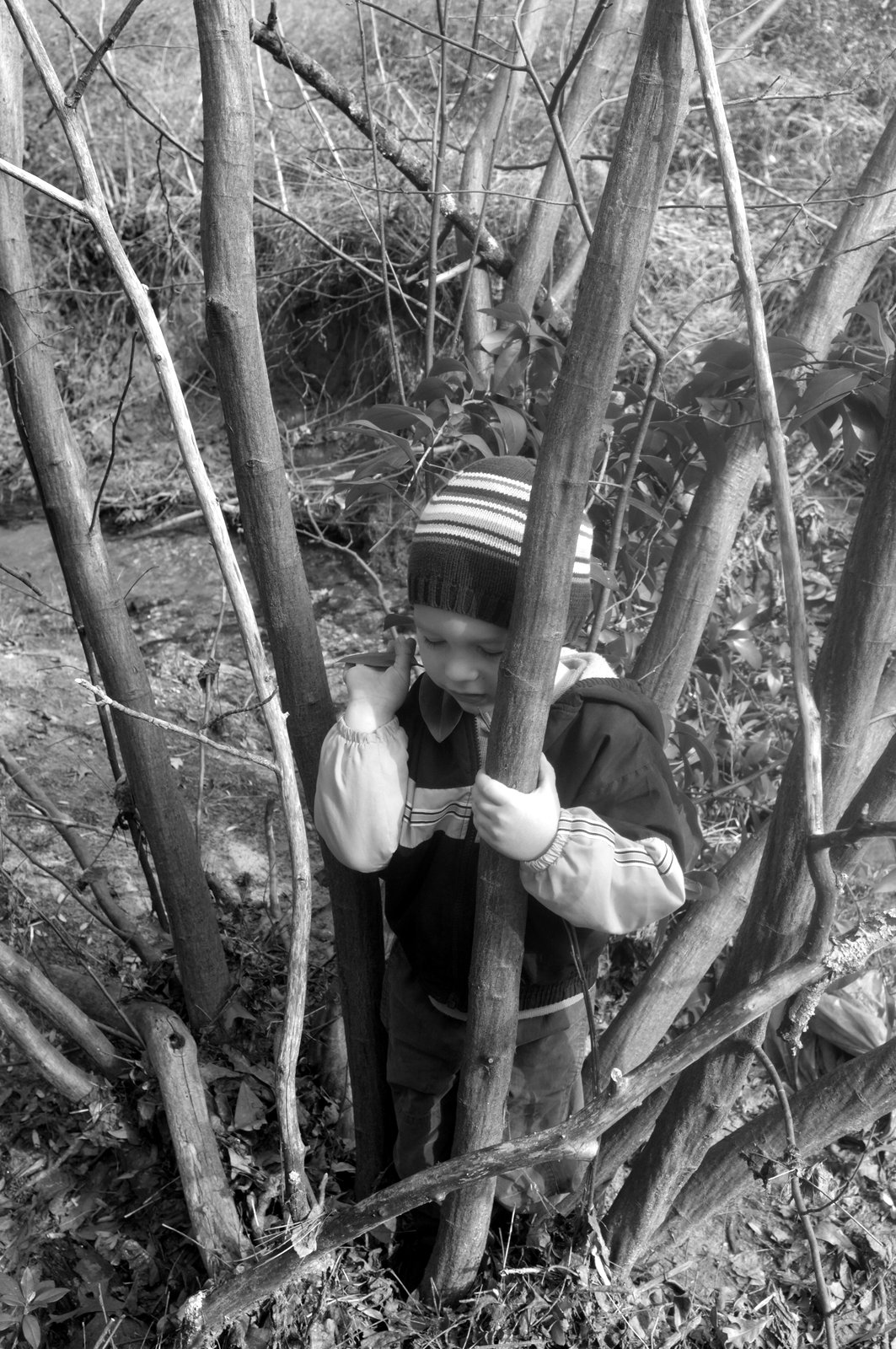

From the moment they woke up, the kids were at the window, ready to go out, ready to play in the snow. “There’s so much snow!” E chirped again and again. It’s only the second or third time the Boy has seen snow, so any snow at all is significant. When Dziadek was sick a few years ago, K to the Boy with her for a visit in the middle of January, and so E saw real snow, deep snow, snow that covers everything and utterly transforms the whole landscape, but of course he doesn’t remember it.

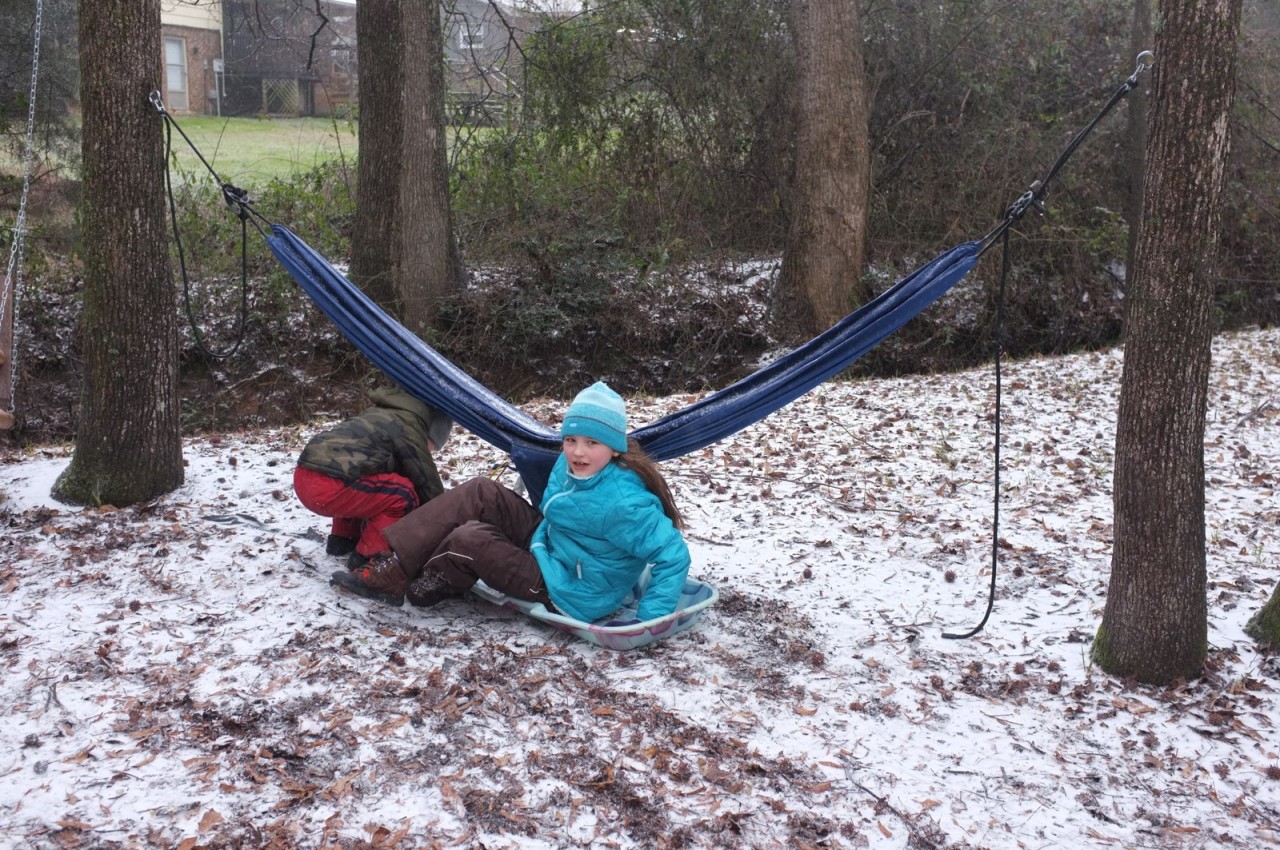

When we finally made it outside, we had a dilemma: the young man who was sledding with us yesterday had come in the morning and taken his sleds with us. What to do? “I guess we sled like I did when I was a kid,” K said. And so we took an old sleeping bag — though, properly speaking, it should have been straw — and used it to stuff a garbage bag. K also thought we might try E’s old inner-tube we used at the pool. “It’s not like we use it anymore.” As the finishing touch, our neighbors invited us to use their yard — slightly smoother and with fewer trees.

When the kids came in, they were soaked. And that’s as it should be.

Snow Day 2016

We don’t get much snow here in the South. Even an inch is enough to disrupt everything. We do get a lot more ice, I think. Even then, the slightest little bit makes the news. This morning, for example, a news caster commented on the fact that there were icicles on the trees, “And they don’t fall off when I shake the branch.” No joke.

Still, when we get a little snow, or even a little ice that is masquerading as snow, we make the most of it.

Relativity

We recently decided to work with Compassion International and sponsor a child in need. We did our research; we determined the organization was reputable; we made the commitment. About the price of going out to dinner as a family once a month.

Our child is H, and he’s an eight-year-old in Burkina Faso, a poor landlocked country in Africa. A few facts from Wikipedia:

According to the Global Hunger Index, a multidimensional tool used to measure and track a country’s hunger levels, Burkina Faso ranked 65 out of 78 countries in 2013. It is estimated that there are currently over 1.5 million children who are at risk of food insecurity in Burkina Faso, with around 350,000 children who are in need of emergency medical assistance. However, only about a third of these children will actually receive adequate medical attention. Only 11.4 percent of children under the age of two receive the daily recommended number of meals. Stunted growth as a result of food insecurity is a severe problem in Burkina Faso, affecting at least a third of the population from 2008 to 2012. Additionally, stunted children, on average, tend to complete less school than children with normal growth development, further contributing to the low levels of education of the Burkina Faso population.

Nothing short of depressing. We feel fortunate to help, blessed to be able to help.

Tonight, we wrote as a family (more or less — the kids were in and out) our first letter to young H. In writing it, I realized anew how ridiculous the Occupy Wall Street slogan “We The 99%” really is, how wealthy my family truly is.

We read in the material we received that there is a three-month rainy season in Burkina Faso, so we asked what that’s like, explaining that it never rains here more than a few days in a row. I thought of our recent flooding in the basement, when the plugs for the termite treatment holes gave way and our basement flooded because of the hydro-static pressure. “The boy probably doesn’t even know what a basement is, and he certainly doesn’t have one,” I thought.

While I was thinking about water, I thought of our problems in the crawl space, where a leak in the line from our sink to the refrigerator (a really old house) caused some substantial damage and necessitated mold remediation and the replacing of a large amount of insulation, something that’s still on-going. These apparent “problems” for us are blessings. We have a refrigerator that keeps our food fresh. We have water from multiple sources in our house. One of his chores, in fact, is to bring water to the family. We use cleaner water in our toilets than H’s family naturally has access to — an absolutely absurd thought.

And so writing a letter to a boy growing up in complete poverty, a boy who would view us as absolutely unimaginably fantastically rick — it was a challenge. “Ask him what toys he likes,” L suggested. Later, helping E clean up his room, I realized that there, spread on the floor, were more toys than H has likely seen in his whole life in one spot. I thought about asking him what’s his favorite subject in school, and then I remembered the fact sheet we received about him explained that he is currently not attending school.

These are of course almost cliche thoughts in the Western world. They are the stuff of dinner-table guilt trips: “You know, there are children in Africa…” We hear it all the damn time. But to have a name, a picture, a short personal history connected to the stories — it makes a world of difference. Suddenly, terrorist attacks in remote countries have personal meaning. World Health Organization statistics have a face behind them. Stock images of houses made of scrap sheet metal become homes.

Last week, everyone in the States it seems was daydreaming and talking about what they’d do if they won the ridiculously huge Powerball jackpot. We could buy this and that; we could do this and that; we could pay for this and that. It’s sometimes hard to remember in the midst of our conspicuous consumption that we are not the 99%. We are the 1%. We have already won the lottery in the eyes of most of the world. The question is, what are we doing with it?

Papa’s Hard Hat

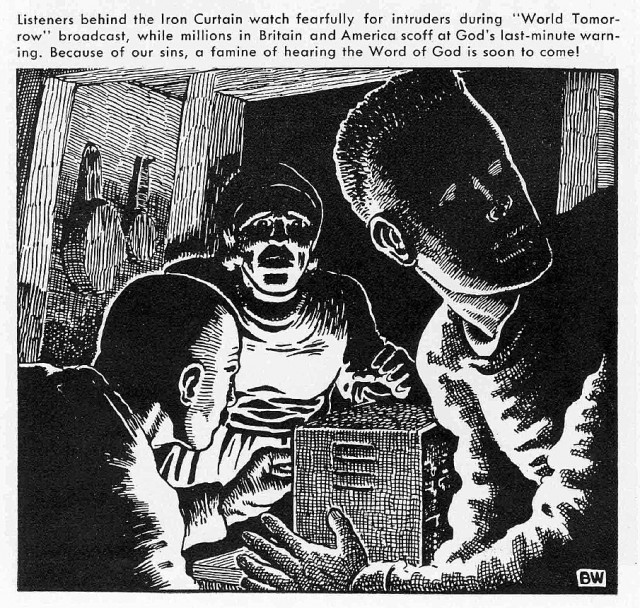

Listeners Behind the Iron Curtain

They huddle around the radio, their attention fearfully divided as they listen both to the thundering voice on the radio and to every little sound outside their darkened hovel. They’re breaking the law, listening to illegal, anti-state programming, and in listening to Herbert Armstrong’s World Tomorrow broadcasts, they’re risking their lives for the truth of Biblical prophecy while those in the free world who have free access scoff.

“What was that!?” the mother whispers in a panic. “Quick, turn it down!” Her husband silences the radio as the teenage son peers into the darkness, straining to hear another sound. Could it be the secret police? If it were, they could be whisked away and put in prison camps in a matter of days.

The three of them remain motionless. No further sounds. Father decides it’s safe.

He turns the volume back up and the three family members continue listening to Herbert Armstrong’s prophetic teachings: German is going to rise again in a Fourth Reich, the revived Holy Roman Empire, which with the Pope as the anti-Christ will crush America and put the survivors into slavery. It’s all prophesied in the Bible if you realize that America and the countries of Western Europe, except Germany, are the Lost Tribes of Israel, while Germany is modern day Assyria. Or something like that.

It’s all silly when you really think about it, and it’s even sillier to think that people still believe that despite the fact that DNA testing has shown conclusively that the only people with Semitic backgrounds are — surprise — Jews and Arabs. But this was the fifties: James Watson and Francis Crick had just discovered DNA’s double helix in 1953, and DNA testing was still a very long way in the future. In the meantime, the Cold War was in full swing, with Kruschev’s USSR just reaching the zenith of its optimism that a state-run economy could produce the paradise that seemed to elude — at least in Soviet propaganda — the capitalists.

But what of these listeners behind the Iron Curtain? The notion came from an illustration in 1956’s booklet 1975 in Prophecy, a digest-size title laying out a timetable for the end of the age. Jesus was to return in 1975, and so the time of trials so many Protestants see as preceding his return would be in 1972. The book purported to provide an “inside view” of the coming tribulation. Within the booklet were illustrations by Mad Magazine illustrator and Armstrong follower Basil Wolverton.

The purpose of such an illustration in 1975 in Prophecy is simple: make listeners in the free, Western world feel guilty for not taking Armstrong’s message seriously. After all, people in Eastern Europe are risking their very lives to listen to The World Tomorrow, Armstrong’s prophecy radio show. But it also worked to create the illusion that the entire world was listening to Herbert Armstrong, further legitimizing his claims of being God’s chosen. World leaders, Armstrong liked to suggest, read his magazine and listened to his radio show, and so literally the whole world must be tuning in. To support Armstrong’s work, then, would be to support a Global Enterprise, and everyone knows that investing in a Global Enterprise is a wise investment indeed. Especially when such an investment could also ultimately help save your own hide.

Just how many listeners were there in Eastern Europe? How many could there be? Given the fact that Armstrong only transmitted in English in the 1950s, linguistic barriers reduce the potential audience significantly. I recall hearing that in all of Poland, for example, in a country of forty million, there was one official church member. Clearly, this was meant for a local audience, then.

Yet that raises a troubling question: is this a lie? For it to be a lie, Armstrong and the administrators of his church would have to know it to be untrue, would have to realize that few people indeed listen to his show in Eastern Europe.

But what if the nature of your self-delusion is such that you see yourself as God’s Apostle on the same level as the New Testament apostles? What if you see yourself as the leader of the one true church, with everyone else in the world deceived by Satan? What if you have surrounded yourself with people who support that delusion? In such a case, believing that people all around the world are listening to your little radio show is a self-delusion of almost insignificant proportions. Of course in the 1950’s, there would have been no metric for a radio audience listening in Eastern Europe, no way to prove or disprove the claim that people are tuning in at the peril of their own lives. And it creates a powerful layer of importance on top of all the other self-delusions: If I am the leader of the only true church (which in a sense would make me the most important person in the world), it only makes sense that people risk their lives to listen to me.

I’ve often wondered about stories I hear about this or that miraculous event, wondering if the individual is stretching the truth in the perceived service of God. Surely that’s unacceptable according to anyone’s moral compass. Yet Machiavellian thinking is dangerously seductive. Could something like that be going on here?

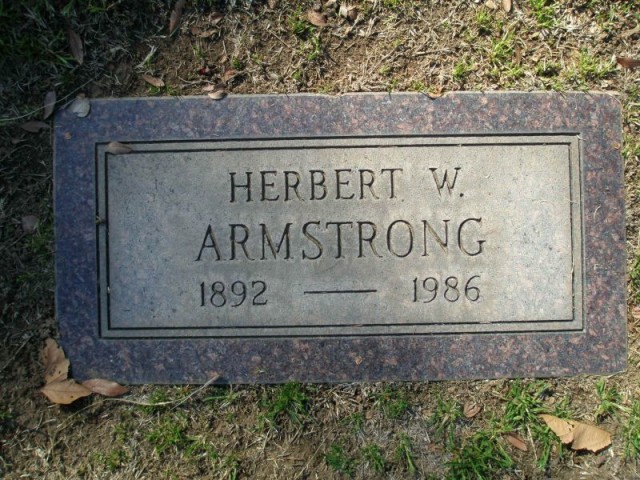

Herbert Armstrong died 30 years ago today. For several thousand in the world, it was an earth-shattering, previously-unthinkable event. For the majority of the world’s population, it was a non-event, just like the majority of other deaths. “Herbert Who?” my classmates and even teachers would have asked. Yet he was a significant-enough player that major news outlets wrote obituaries. The New York Times wrote the following:

LOS ANGELES, Jan. 16— Herbert W. Armstrong, the broadcasting evangelist who was founder and pastor general of the Worldwide Church of God, died today at his home in Pasadena, Calif. He was 93 years old. Church officials said no official cause of death had been established, but they added that Mr. Armstrong’s health had been declining about four months because of a heart ailment.

Mr. Armstrong presided as the ”Chosen Apostle” of God over the wealthy fundamentalist Christian church, as well as over the Ambassador College and the Ambassador International College Foundation, both in Pasadena. The Ambassador Auditorium on the campus is a lavish concert hall where famous musicians and artists have performed.

The church publishes Plain Truth magazine and broadcasts television programs on 374 stations around the world, David Hulme, a church spokesman, said.

Officials of the 80,000-member church announced last Tuesday that Mr. Armstrong had named Joseph Tkach, 59, as his successor. Ralph K. Helge, the church’s general counsel, said in a statement that Mr. Armstrong had felt it was time to ”pass the baton” and establish a new spiritual leader to avert dissent when he died. Advertising Career, Then Radio

Herbert Armstrong was born July 31, 1892, to Horace and Eva Armstrong in Des Moines. In 1934 the young Mr. Armstrong abandoned a career in advertising to found the Radio Church of God in 1934 with the first broadcast of his program, ”The World Tomorrow.”

He incorporated his California ministry in in 1947 as the Worldwide Church of God and began spreading his conservative beliefs with alternately fiery and folksy sermons. The religion is a blend of fundamental Christianity, non-belief in the trinity and some tenets of Judaism and Seventh-Day Sabbath doctrine.

Members pay the church at least 10 percent and as much as 20 to 30 percent of their income, and celebrate Passover and Yom Kippur as holy days rather than Easter and Christmas. Mr. Armstrong espoused creationism and enjoying material wealth as a sign of divine favor; he held that he was preparing his followers for a Utopia to be ruled by Jesus.

Controversy and Feud With Son

The church has been embroiled in controversy, ranging from the estrangement of Mr. Armstrong and his son, Garner Ted Armstrong, to lawsuits by former church members and an investigation by the state Attorney General of reports of mismanagement of church funds.

As membership swelled in the mid-1970’s, trouble arose between Mr. Armstrong and Garner Ted Armstrong, his youngest child and heir apparent. The son appeared weekly on 165 television stations across the country as the voice of ”The World Tomorrow” and was executive vice president of the church.

The church had a strict policy against remarriage for divorced people that required new church members to dissolve second marriages and remarry their original spouses. Garner Ted Armstrong vehemently opposed rescinding that order and his father’s subsequent marriage in 1977 to a second wife, Ramona, 44 years old and divorced. His first wife, Loma, died in 1967. He divorced the second in 1984.

Mr. Armstrong and his son also argued over control of the college, the auditorium, and other holdings. Herbert Armstrong excommunicated his son in 1978.

Case Led to Curb in Law

Garner Ted Armstrong, supported by some former church members, subsequently charged that his father and other officials had spent millions of the church’s estimated $60 million annual income on personal expenses. In 1979 the Attorney General’s office got a court order to place the church in receivership, saying the officials had ”looted” $1 million a year from tithed funds.

The case was dropped in 1980 after a new state law, prompted by the Armstrong case, prohibited the Attorney General from investigating the finances of religious groups for fraud and mismanagement.

The father-son rift was never healed. ”I tried repeatedly to contact my father up until two weeks ago, but it was all to no avail,” Garner Ted Armstrong said in an interview from the headquarters of his Church of God International at Tyler, Tex. ”He had a heart condition, and I knew his health was failing quite rapidly. My sister said he died quietly while sitting in a chair.”

Herbert Armstrong also leaves his daughters Beverly Gott and Dorothy Mattson, eight grandchildren and four great-grandchildren. Arrangements for private funeral services are pending. (Source)

Thirty years later, and it’s such a different world for everyone mentioned in the article. Armstrong’s successor, Joseph Tkach, is dead, and his successor, his son, is still running the original church, though it reformed twenty years ago and even changed its name.

There are still those who follow the man’s teachings, though. A few thousand scattered among a few dozen off-shoots. The leaders of several of those churches are now in their seventies or eighties, and the pattern will repeat itself.

Śpij, kochanie

“Daddy, I want to go to sleep.” And so I put up the book, turn off the light, and start the music.

The Boy rolls over on his back, and I rest my arm along his back, running my fingers through his hair gently. He stops moving, his breathing slows, and within moments, he’s asleep. Still I lie, continually stroking his head, rubbing his back. He takes a deep breath, lets it out, and sinks deeper.

W górze tyle gwiazd,

W dole tyle miast,

Gwiazdy miastu dają znać,

Że dzieci muszą spać.

Just listening to the Polish lullaby gets me thinking of all the twists and turns it took to get me to this moment in which I’m listening to a song in a language I never dreamed of learning, thinking how appropriate the lyrics — “Above, so many stars / below, so many cities. The stars let the cities know / That it’s time for children to sleep” — are some nights when the Boy tosses and turns and turns and tosses as my Polish wife puts our daughter to bed in the next room. All those little twists and turns, those seemingly insignificant decisions that led to meeting, returning, dancing, flying — all the things that led to the present moment, the present family.

“It was fate,” some might say. “It was the hand of God,” others might rejoin. “It was a happy sequence of accidents,” still others might insist. Fate, accident, God — whatever the cause, I’m grateful for all the steps, trips, and slips that led to this moment. Remembering that on a regular basis, I think, is the key to happiness.

Diagram

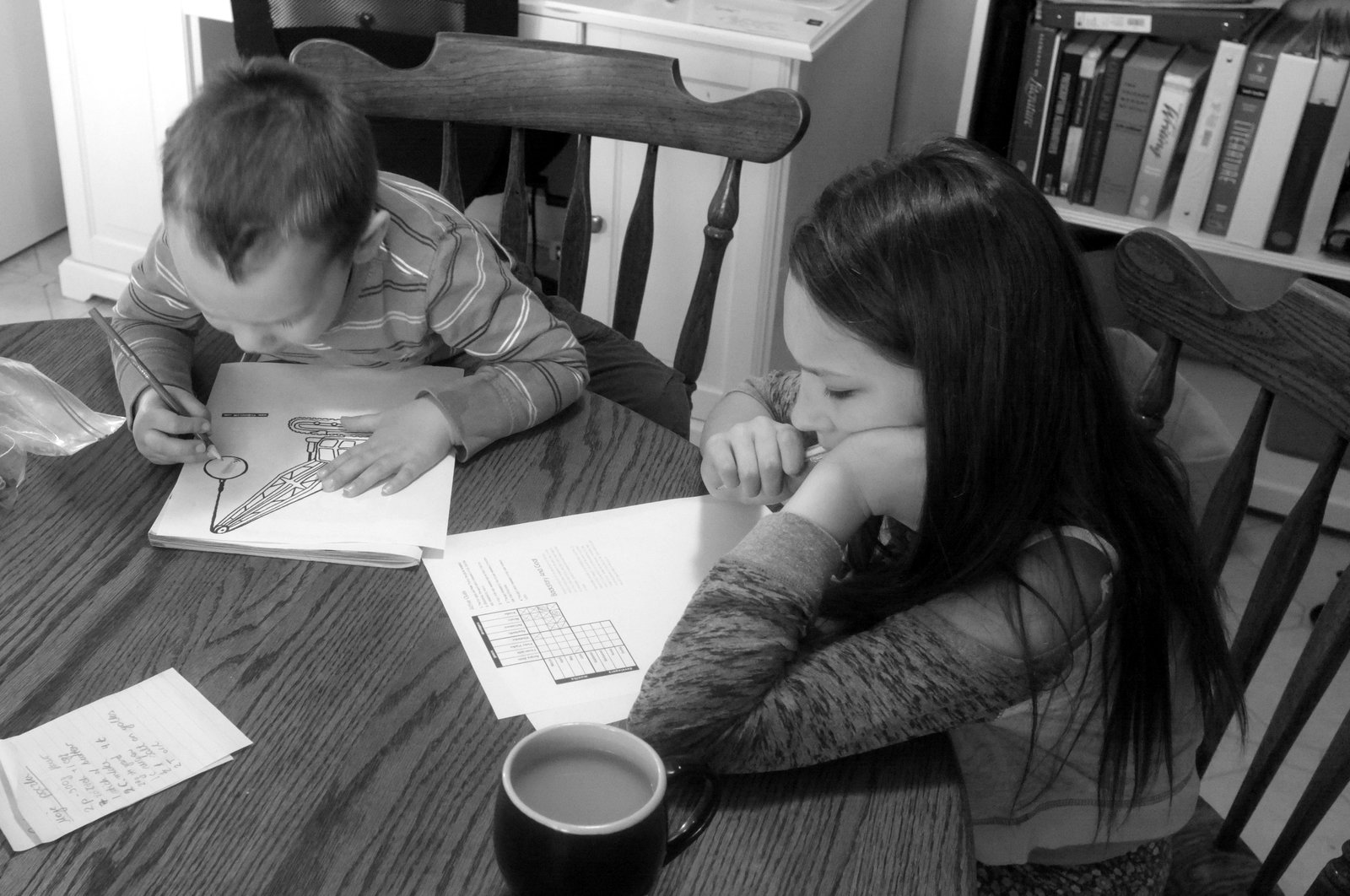

L and I were sitting by her bed, reading the graphic-novel version of Shakespeare that she brought from the school library when she came across a sentence that stumped her: the king sent to men “to consult with the oracle of Delphi, in Greece.” I explained to her what “consult” means and then began working to help her figure out what “oracle” might mean.

“If ‘consult’ means something like ‘ask advice from’ and the men went to consult with the oracle, what did they ask advice from?” Much to my surprise, she couldn’t figure it out. I explained that the verb was “consult,” the action is “consulting.” “So who’s doing the action, who is consulting?”

“The king?”

It was clear a new strategy was necessary.

That’s right, I started teacher her how to diagram sentences. There are few skills that are so incredibly useful for getting students to see the inner working of a sentence, the clockworks of the sentence. Of course it’s no longer taught today except by eccentric English teachers who have free reign with their curriculum design — in other words, it’s not taught anymore. Still, I’ve begun wondering if I could somehow incorporate it into my own teaching

43

Birthday, Thirty Years Earlier — today’s entry from Anne Frank’s diary:

Wednesday, January 13, 1943

Terrible things are happening outside. At any time of night and day, poor helpless people are being dragged out of their homes. They’re allowed to take only a knapsack and a little cash with them, and even then, they’re robbed of these possessions on the way. Families are torn apart; men, women and children are separated. Children come home from school to find that their parents have disappeared. Women return from shopping to find their houses sealed, their families gone. The Christians in Holland are also living in fear because their sons are being sent to Germany. Everyone is scared. Every night hundreds of planes pass over Holland on their way to German cities, to sow their bombs on German soil. Every hour hundreds, or maybe even thousands, of people are being killed in Russia and Africa. No one can keep out of the conflict, the entire world is at war, and even though the Allies are doing better, the end is nowhere in sight.

As for us, we’re quite fortunate. Luckier than millions of people. It’s quiet and safe here, and we’re using our money to buy food. We’re so selfish that we talk about “after the war” and look forward to new clothes and shoes, when actually we should be saving every penny to help others when the war is over, to salvage whatever we can.

The children in this neighborhood run around in thin shirts and wooden shoes. They have no coats, no caps, no stockings and no one to help them. Gnawing on a carrot to still their hunger pangs, they walk from their cold houses through cold streets to an even colder classroom. Things have gotten so bad in Holland that hordes of children stop passersby in the streets to beg for a piece of bread.

Halušky

Reading

I give the students the same information every year, but this year, I decided to break it down in a letter. Dear student, you recently took the MAP test, which measures your reading progress. And so on and so on. It’s a mail merge, so “student” is replaced with the kid’s name, and all the details are individualized. Like the winter score. Like its grade-level equivalent. It’s bound to be a disheartening moment for some: I’m not sure they’ve ever been told point blank, “Your reading scores indicate that you’re reading at a second-grade level.” How do you take the news that your skills are six years behind where they should be?

There are a number of reasons one could posit for this, and for each, a exception: For some, it’s a question of limited English exposure at home. But I have Latino students in my honors high school courses as well. For others its a question of limited access to books. But I have such students in my honors high school courses as well, and they solve the problem by basically camping out in the school library. No role model in the immediate family to provide the support necessary. But I’ve had students in my honors high school courses who’d never even met their biological father.

At times they seem like excuses, at times they seem like legitimate — and tragic — explanations. Whatever the case, they’re my charge, and I’m tasked with reversing the trend. Some days, though, it just feels like I’m making the situation worse still.

Sunday in the Park

The patriarch of the Buendía family, José Arcadio Buendía, spent the last days of his life under the chestnut tree in the courtyard of his home. Even when villagers carried his body to his bed as his end became increasingly obviously near, he woke and went back to the tree every morning as “a habit of his body.” Thus Marquez describes it in his classic One Hundred Years of Solitude, which I am re-reading some twenty or twenty-five years after I first read it. The idea of a habit of one’s body stuck with me all these years, and tonight, when I finally read that scene, I smiled. It was one of the passages of the novel I couldn’t recall where exactly it fell but read eagerly in search of it.

Part of the joy of watching children, I think, is that they have no habits of the body yet. They don’t get up at five thirty and make the morning coffee without thinking about it. They don’t come to an intersection intending to turn right but pulling into the left lane out of habit. They don’t have a routine they follow in which they suddenly become aware they’re half-way through the routine. Every action is new. Every action has a certain uncertainty to it that demands their attention and their care. Every act brings forth a joy of the novel.

Family Reunion

Peeling Eggs

The Boy is always eager to help, especially when it comes to cooking. Any time K is standing at the stove, E bounds over to the dining table, grabs a chair, and slides it across the whole room to the stove.

“I want to help!”

Most often, that’s just stirring. It’s simple, difficult to mess up, and difficult to make a mess doing. Today, though, as I was rinsing the boiled eggs we’d be putting in our żurek later, he decided he wanted to learn how to peel the eggs. Rather, having just woke up from a nap, he was encouraged to learn. Bribed, for he’s awfully fussy when he’s awakened prematurely.

“Want to help me cook?” I began.

He was reluctant at first, but the words “learn” and “something new” seemed to pique his interest, and soon enough, he was peeling an egg.

When it came time for dinner, he was quite insistent that he got the egg that he had peeled.

“Bardzo słuszna koncepcja.”

Why a Jet?

First Day Returning

The first day back can always be stressful: you walk back into the school wondering what kind of day the kinds have packed in their book bags and hauled to school from Christmas break. Some years, they unpack a chattiness and an unwillingness to work that in a lot of ways is understandable. Other years, they haul out their books and their attention and make the day slide by almost effortlessly.

It occurred to me that I could help them pack their bag by having them leave on a good note, hence my opłatek efforts at the end of the year. Through most of the day, I thought that perhaps it had worked, that perhaps ending the year on a deliberately positive note helped bring them back with a positive outlook. They worked brilliantly, and not a complaint as I introduced and modeled a new weekly assignment, the article of the week, based on Kelly Gallagher’s ideas.

The final period of the day rolled to a close, and one young lady who was absent the final day asked me if I’d saved a cookie for her.

“Excuse me?”

“The cookies you gave everyone before the break.”

Here it was — definitive proof that what we’d done together had made an impact, for someone had clearly told her about the experience. Obviously it had struck something in their souls, made them resonate as one for a moment, showing them the oneness of humanity and all the hopes and dreams of everyone who has ever set out to create a utopia.

“Oh, yes,” I replied. “How did you hear about them?”

“Oh, everyone was just saying they were really tasty.”

A utopia for the taste buds, I guess, is better than no utopia at all.

Final Sunday of the Break

Just as predicted, we blinked twice and it was Christmas Eve; another two blinks and it was New Year’s Eve. And now, it’s all over again. Another Christmas break is little more than memory. But that’s not a bad thing: Most of our lives are memory. The present is just a passing phase that disappears as soon as you acknowledge its existence. The future is relatively uncertain. So it’s our memories that make up the majority of our life.

Today was glorious, but we were all tired, so we stayed home. It was a lazy day from the beginning: the alarm went off at seven, and it took only a moment for K and me to decide that the eleven o’clock Mass was a better option than the nine o’clock Mass.

We were thinking about going for some afternoon outing, perhaps hiking somewhere, but soon after Mass, as we were heading to the car, I think I’d decided that even going to a nearby park might be too ambitious.

So in the end, we spent the day at home. There was an abundance of trampoline time, including the fun game of Charge Yourself with Ample Static Electricity by Shuffling Around the Trampoline with Your Socks On Then Discharge It All Onto Daddy’s Bald Head. A fun game, that.