The Wheels on the Car

Helping

It’s been going on for almost a week now, this bi-yearly deck project. It’s taken a bit longer each time around, and while I try to tell myself that this is because of unforeseen rain, lack of materials, or something similar, I suspect that the speed with which I do it contributes. The cleaning and staining of the the deck is something that works best during hot, clear days, and these days, I work about forty minutes to an hour, and I feel compelled to go back inside and cool off.

Getting a helper today was really an unexpected treat. First, there’s the help. Sure, there was the learning curve. And yes, yes, I did have to go back and correct some runs — it’s the poor girl’s first time, for heaven’s sake. What do you expect?

But for a beginner, she certainly showed she was a quick student with a good eye for detail.

The second reason, of course, is the simple fact of who my helper was: to have your daughter be willing to help without any cajoling or bribery is a precious thing. Okay, there was a reward, but that was after the fact, after the agreement to help, after the work was done, but she didn’t know about it when she agreed to help out.

The proof: disappointment when I told her she was done.

“Well, can I paint this?” she asked. “What about that?” I finally found some work for her, but not enough to fill the time I had left rolling stain onto the floor, so she just sat and chatted with me.

The Boy loves to help as well. His independent streak is a bit more developed than his skills are, and he often insists, in Polish, that he do something alone (“Sam!” he says), but that desire is there, and we can easily channel it.

Some days it’s as easy as channeling water; other days, not so much. But that’s what being two is all about.

Summer Mornings

Of our two, the Boy is always the first to wake up; indeed he’s often the first of the four of us. But these summer days, there’s a definite order: K, E, I, and then L. And it’s E that wakes up L. He toddles down the hallway, calling, “L, get up!” He climbs up on her bed, rolls around a bit, and then proclaims, “Time to get up!”

By this time, I’ve walked into the room, and E, worried that L is still asleep, suggests a more direct method of waking the Girl.

“Jump on L?” he asks, head cocked, as if he were simply asking if I would like him to bring a dirty plate from the table for washing.

“No, no, don’t jump on sissy.”

He turns to the window.

Cukes

Monopolizing

With one child, it was easier to make sure that we spread our time evenly. L had a monopoly. We played games with her, talked to her, cuddled with her. With her and only her.

When E came along, we warned her that things would change, that she’d have to share: time, attention, resources. Not love. Somehow that spread effortlessly, but the signs of love, the signs of love for a seven-year-old, anyway.

But with the Boy deep in his afternoon nap on a Wednesday afternoon, it’s time for a bit of that old monopoly.

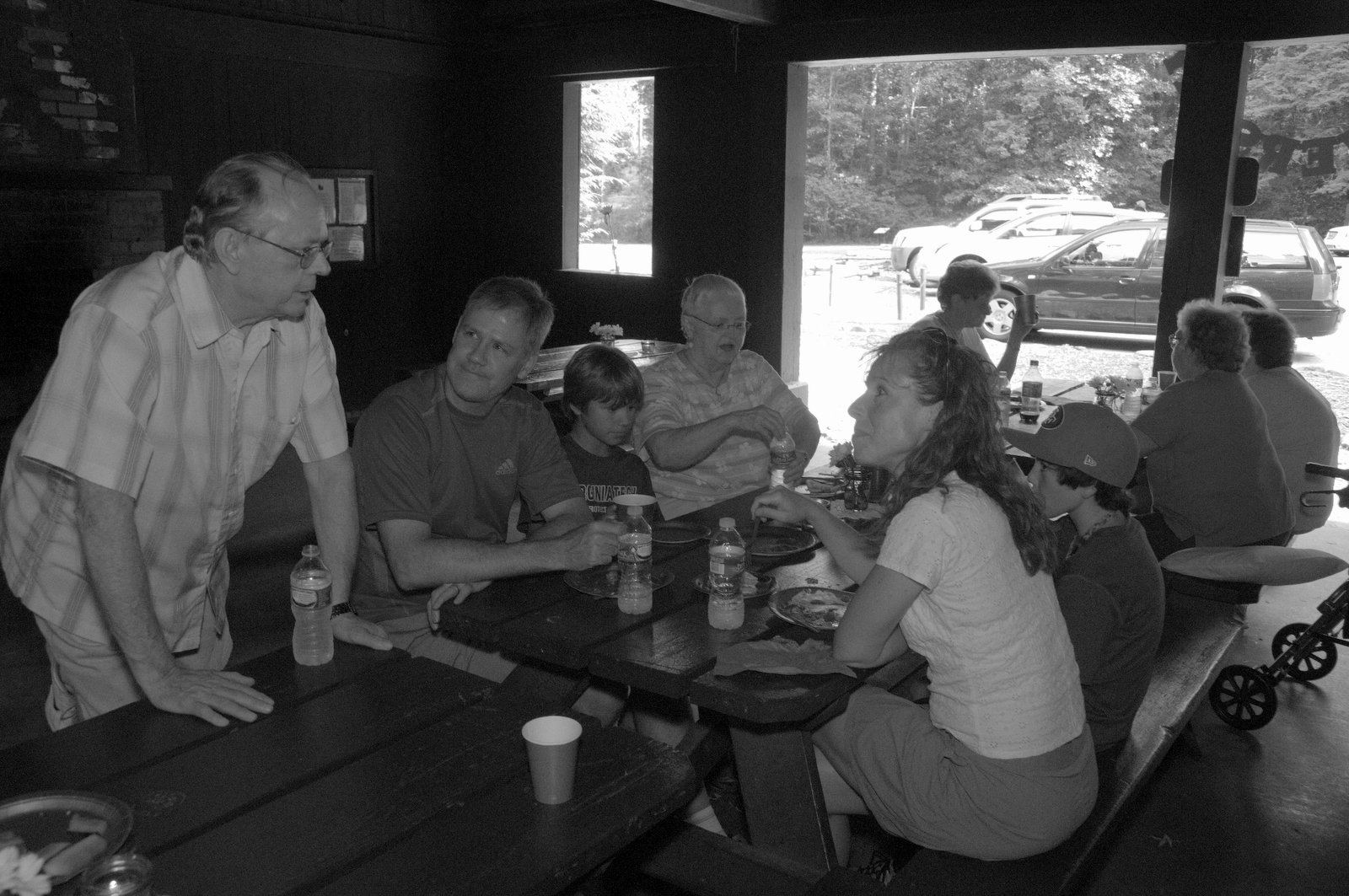

Conestee Summer Evening

The Boy is fearless on his four-wheel scoot-along (what the heck is that thing?). He comes barreling down our driveway at dizzying speeds, velocities that can stop a parent’s heart, if only briefly until he begins braking by dragging his shoes.

The Girl roars down the driveway even faster on her scooter, but that’s less worrisome: she’s seven, after all. More coordination, more understanding of the risks (though that only seems theoretical at times).

This evening we decided to take them both to a local favorite park for a little workout of these skills.

The Boy, though, had other interests.

Still, we managed to get them both together for just a moment for a picture from the newest observation deck.

And then the Boy showed just how sweet he can be.

The Queen of England

Sure, I’m just basing this claim off anecdotal evidence I’ve experienced in my own classroom, but I’ll make the claim nonetheless: today’s kids just don’t have the imagination of past generations. I base this on the experience of students in creative writing classes having nothing to write about, and when given help with discovering the wealth of topics that surrounds them, they usually wrote about video games or thinly veiled remakes of various films.

The scene that greets me almost every day arriving at school goes a long way in explaining this, I believe.

The Girl, at this point, doesn’t suffer from such a lack of imagination. She’ll take a blanket, old sheer for window treatments, and heavy winter gloves and declare herself the queen of England.

Dig!

Fifty Years in the Making

Pickles and Picnics

The Boy has some strange tastes, some strange favorites: pickle juice is a favorite drink. Finish off a bottle of pickles — the American, vinegary type — and he’ll jump on that bottle immediately.

The Girl has always had some strange tastes, too. It’s only been in the last year that she’s even ventured to try that favorite of American kids from coast to coast, the humble (and not-so-good-for-you) hot dog.

What to make to make of this? Nothing more than the obvious: kids too are individuals, and their tastes grow and change with time. For now, we’re happy the Girl loves so many Polish soups and the Boy just loves everything. Likely to change, but for now, it’s good.

Without the Girl

The Girl was out for most of the day. VBS in the morning (that’s Vacation Bible School, not the inferior Microsoft scripting language) and a Nana/Papa day in the afternoon.

We boys hung out together in our fort,

rode our bikes.

Helping

Na Oko

“Ile czosneku dajesz?”

“Na oko, na oko.”

When you’re getting recipes from Babcia, they tend to take that turn. “How much garlic do you add?” you might ask. “Just eyeball it,” comes the reply.

How can I possibly eyeball it when I’ve never done it in my life? Dziadek taught me in a similar way how to prepare the brine for meat when preparing pork for smoking. It was actually experience that taught me that, in reality, the proportions don’t matter so very much as you might expect.

Given the fact that the instructions Babcia provided for making pickles roughly approximated the instructions Dziadek gave for making the brine, I just eyeballed it.

Dill, whole allspice, some garlic, bay leaves — the Polish basics. I decided to add some fresh oregano and basil, knowing it probably wouldn’t have any effect given the amount of other spices I was putting in the brine.

I’ve always loved pickles, but it was in Poland that I learned what a true pickle could be, not preserved in some vinegar solution but made in a brine that leaves behind the look and taste of raw cucumber but transforms it just enough that it’s not, well, raw cucumber.

Given the number of cukes we’re pulling off our vines every day this year, we knew fairly early in the growing season that this would be the year we finally learned how to make our own pickles. Such a simple process: some herbs, some salt water, some cucumbers, a ceramic pot, and a bit of gauze to cover it all.

“You should be able to eat the smaller ones after four days or so,” Babcia explained. It might be difficult to wait that long.

What To Do on a Hot Afternoon

Cycles

When the Girl was little, Big Wolf was a popular guy who helped us pass a lot of hours.

“Shhh!” L would exclaim. “Big Wolf coming!” We would dive under whatever cover we could find and count down so that together we might sit up and command, “Big Wolf! Walk away!”

One day in the zoo, we found a plush wolf and knew what we had to do. It remains a highlight for us, a story K and I can retell with a smile, making L smile now too.

Time passed, though, and L grew, and the things that once thrilled her no longer did so. Big Wolf soon became one of many plush toys packed into a net hanging in the corner of her room. Forgotten? Not quite. But almost.

In recent days, the Boy and I have begun playing “Big Wolf” again. He holds his index finger to his lips, shushes us, and proclaims, “Oh! Big Wolf!”

We most often do it in the hammock, a recent discovery for us both. Three days in a row now we’ve gone down the the blue hammock in our wooded backyard and lay there as the evening sun sets all the leaves above us aglow. Just as with L, we play that we must pretend to be asleep in order to keep from provoking Big Wolf. The Girl has brought E her wolf plush toy, and now the Boy must have Big Wolf in the crib at all times, nap and evening rest.

The Girl in the meantime continues to create new cycles for the Boy and me to repeat later. Trips to the pool become lessons in sitting on the bottom of the pool, managing to touch the bottom at the deep end, and holding one’s breath for extended periods. Just as E is now, L was once terrified to put her face in the water, horrified at the thought of getting a droplet of water in her eye, and completely frightened of the deep end. Sooner than we realize, the Boy too will put away Big Wolf, take up his goggles, and tell me, “Tata, teach me a new pool trick.”

Regret and Repetition

It’s early June: my thoughts always turn to an arrival in Polska. I wrote this last summer, after our return, and discovered only now that I had never posted it.

1

“Never regret anything, because at the time, it was exactly what you wanted.”

When I went to vist the school in Lipnica in which I taught for seven years, the English teacher, a former student of mine, invited me to her English lesson. As she was taking roll, I wandered about the room, looking at how the relatively new Foreign Language Workshop had been decorated. I found a poster with English sayings, including one about regret that I couldn’t recall ever having heard.

“Never regret anything, because at the time, it was exactly what you wanted.”

“So true,” I thought initially. Further thought made me wonder, though: perhaps this quote takes a simplistic view of both desire and regret.

Desires don’t come from nowhere. They aren’t frivolous imps that leap into our head, unbidden, unwanted. They arise, consciously or unconsciously, from our values, habits, and worldview. As a Catholic, I have to view some of these desires as sinful, as inherently evil. They are temptations, and I am called to overcome those temptations. If I choose not to, I’ve betrayed God, myself, and to some degree or another, my fellow humans. (After all, the Confiteor we Catholics all recite at the beginning of Mass includes this notion: “I confess to almighty God and to you, my brothers and sisters, that I have greatly sinned, in my thoughts and in my words, in what I have done and in what I have failed to do, through my fault, through my fault, through my most grievous fault; therefore I ask blessed Mary ever-Virgin, all the Angels and Saints, and you, my brothers and sisters, to pray for me to the Lord our God.” Emphasis added.) So if these desires are temptations to sin, and I give in to these temptations, and later I want to repent, how can I possibly not regret them? True, these actions were exactly what I wanted at the time, but that was because I don’t yet have a perfectly formed conscience. Further, if I don’t truly regret the sin, how can I confess the sin?

Yet not all desires are sinful desires, and yet we still end up wishing we had made different choices. Is this regret? I suppose. Is it the same kind of regret discussed above? Somehow, it seems different. Perhaps, then, we need to differentiate, look at some synonyms:

apologize, be disturbed, be sorry for, bemoan, bewail, cry over, cry over spilled milk, deplore, deprecate, disapprove, feel remorse, feel sorry, feel uneasy, grieve, have compunctions, have qualms, kick oneself, lament, look back, miss, moan, mourn, repent, repine, rue, weep, weep over

“Regret” seems the correct term for the theological notion associated with sin and forgiveness, as do deplore, lament, and grieve. For the second, less theological (and in some senses, then, less important or significant emotion), miss, feel sorry, or even rue seem appropriate. Working with those differentiations, I regret some of the sinful choices I’ve made in the past, which means I wish not to repeat them; I rue some of the poor decisions I made in the past, which means to me not so much that I wouldn’t make the same choice but that I dislike some of the consequences that came with that choice. I rued having left Poland, so I went back.

I think early in my life, I confused those two forms of regret, as do many people, I think, and that confusion as the source of the quote got me thinking of all this. In my case, I disavowed the existence of theological regret, and I overemphasized the things I rued.

2

Every time we come to Poland, we repeat: Krakow, Zakopane, even the outdoor museum in Zubrzyca (though this year, it was part of a class trip with L). This repetition is understandable in large measure because much of the repetition comes from meeting with friends and family. Yet it doesn’t change the fact that very little changes in our visits to Poland.

It occurred to me, though, the other night that part of it might be an unconscious unwillingness to move outside of a certain comfort zone in Poland. Yet that seems simplistic: it’s not as if I don’t know my way around the country and culture; it’s not as if I’m fearful of new situations here. I speak the language with passable proficiency: there are few times that I feel unable to express myself, and I even managed to talk myself out of trouble a time or two.

Yet as I wandered about the fields of Lipnica, with views I know almost better than the area in which I grew up, I wondered if it might be something else, something that I hadn’t experienced in literally years but which I knew all too well earlier in life, and multiple times at that. It struck most forcefully in 1999, when I left Poland for the first time and soon found I was desperate to return to Poland. It wasn’t that I wanted to return to the place as much as I wanted to return to that part of my life, to relive it in a sense. Returning for a short visit in the summer of 2000, I found a line from a song running through my head constantly, for I wanted to “hold on to these moments as they pass.” And so it occurred to me one evening this summer in Poland that I do the same thing every visit, revisiting places in order to relive the past, if only for a brief moment. Then that moment passes, we all move on, temporally and physically, and I find myself later reliving the relived moment again, only in my mind.

And so I find comfort in the places that haven’t changed much over the years. The exterior of the teachers’ housing block in Lipnica, for example, hasn’t really changed a bit since I first arrived in 1996. There are new windows; there is a new flue for the oil furnace in the basement; there are a few more cables strung across the facade. Other than that, though, it looks identical. It gives the illusion that, while the rest of the world has moved on, I’ve stayed the same, which is a ridiculous notion. But for a brief moment, it’s comforting.

Why?

Human time does not turn in a circle; it runs ahead in a straight line. That is why man can’t be happy: happiness is the longing for repetition.

Milan Kundera

The easy answer is that it’s a vain attempt to deny my own mortality to myself, the stuff ironically both of melodrama and of great literature. And while there might be some element of unconscious truth to that, I don’t feel I really fear death or even give it much of a thought at all. Occasionally in the last few months I’ve surprised myself with the realization that I’m now in my forties, but this is not a mid-life crisis but a how-time-has-slipped-by-so-quickly crisis. And besides, this doesn’t explain the same longing I felt — only much, much more intensely — in 1999 and 2000 that led to my return to Poland. Surely I wasn’t fretting about my mortality in my mid- to late-twenties. Only nineteenth-century poets do that.

The longing, in fact, was much simpler (and significantly more naive) than that. It arose from the fear that the past was better than the present, and worse still, that the past was likely better than the future. A bit melodramatic, I’m sure, but those were the worries and concerns I had at times. It explains a lot of the angst I experienced when younger.

I no longer feel that way at all, though. Children make it impossible to look backward with the same longing. Children make it impossible to think the past was better than the future. Children make it impossible to regret the passing of time. Hence, as I wandered the fields of Lipnica, that strange longing to return to the past, while present, was only so strong as for me to notice its relative absence in recent years.

Re-reading Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being, though, I discovered a forgotten quote that had so struck me the first time I read it that I made not of it on the slip of paper I’d slid into the back of the book and discovered as I opened it anew a few days ago. “Happiness is the longing for repetition.” Perhaps I’ve had it wrong: perhaps this repetition is simple happiness?

Children understand this simple truth: it’s why they can say or do the same thing over and over and over and over and still find it just as funny and enjoyable the tenth time as it was the first. It’s why they can swing — the ultimate in repetitive activities — for hours on end and still do the same tomorrow.

Religions understand this simple truth: it’s why all religions have ritual calendars, calling for the repetition of rituals throughout the year for all eternity.

Another Day, Another Park

“I don’t want to go to the park! We went to the park yesterday. We went to the park the day before yesterday. I’m tired of the park. I’m sick, sick, sick of the park.”

Thus we began our morning. Breakfast, a bit of My Little Pony on Netflix, some freshly picked raspberries and blackberries — none of these things, which some might be tempted, incorrectly I might add, to call bribes, worked. On the way to the car, it was the same.

“I’m taking my Pokemon handbook,” she huffed. “I don’t want to play.”

Of course by the time we got to the park, she’d reconsidered and thought she’d just give the playground a try.

“If not, I’ll go get my book.”

Naturally, she never went to get her book. How could she when the Boy was on such a roll: afraid of nothing, he even went down the big slide — and I mean big slide — all by himself. He panicked a bit on the way down, which is why he burned his forearm on the smooth plastic and probably explained that wide-eyed look he had, but it wasn’t enough to keep him from trying again.