Letter from a Former Student

I simply adore my school and the people in it, especially the teachers. I haven’t had any English teacher as great as you though. I still value and appreciate your teachings. You greatly influenced my writing by inspiring and cheering me on. Every time we receive a writing assignment, you appear in my mind.

Enough to make you puff your chest out a little more…

Crawl Space

Sometimes, rooting about in the crawl space, taking care of mold in anticipation of new insulation being put in, you find something you just wish you hadn’t found. Like a dead bird. Or something worse.

Sign Language

Early Morning with the Boy

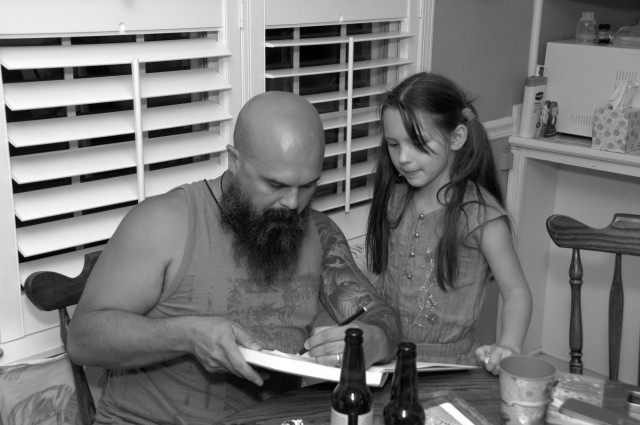

The Boy’s sleeping schedule is somewhat more flexible than we’d probably really like it to be. It probably has to do with that stubborn illness that’s been lingering.

Some days, he sleeps until eight; other mornings, he’s up at half-past five. It would be infinitely convenient if the former days tended to fall on the weekends and the latter during the work week, but infinity and convenience are rare companions. And in the end, isn’t convenience overrated?

Besides, when we’re the only two up — K already out of the house and L asleep — it’s reminiscent of the early weeks. Tiring weeks, but always magical in the morning.

“Magical morning my foot,” K might say. “I remember how you complained!”

Bell Ringer

The idea is to get students working immediately. They walk into the classroom and find work projected on the Promethean board and are to get started.

From today.

| GATHER ye rosebuds while ye may, Old Time is still a-flying: And this same flower that smiles to-day To-morrow will be dying.The glorious lamp of heaven, the sun, The higher he ‘s a-getting, The sooner will his race be run, And nearer he ‘s to setting.That age is best which is the first, When youth and blood are warmer; But being spent, the worse, and worst Times still succeed the former. Then be not coy, but use your time,And while ye may, go marry: Robert Herrick. 1591—1674 |

AND AFTER YOU’RE DONE GATHERINGYE ROSEBUDS, GATHER YE STARTERS WHILE YE MAY. OLD MR. SCOTT’S A-CHECKING THEM TODAY |

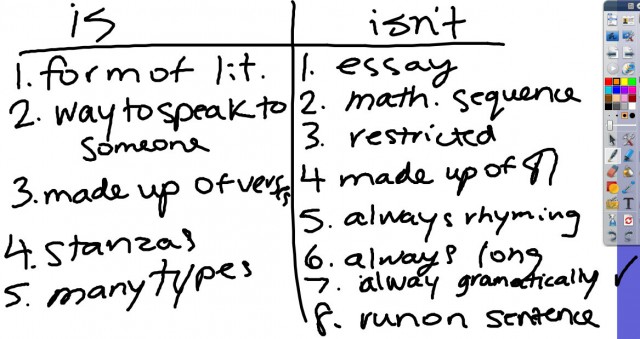

About the Difference Between Prose and Poetry

Because They Asked

Simple instructions — the starter — great them when they enter the classroom.

Complete: “Poetry is…”. Write at least five facts about poetry. Then complete “Poetry isn’t…” and write five more things poetry isn’t.

They get started scribbling a list, a list we will share and debrief once I’m done checking roll and making sure I have all my materials for the day’s work in order.

Then the poem: “Because You Asked about the Line Between Prose and Poetry” by Howard Nemerov.

Sparrows were feeding in a freezing drizzle

That while you watched turned to pieces of snow

Riding a gradient invisible

From silver aslant to random, white, and slow.There came a moment that you couldn’t tell.

And then they clearly flew instead of fell.

After reading a couple of informational texts about how to read a poem, students try their hand at Nemerov’s analogy:

prose : poetry :: sleet : snow

It’s slow going at first, for it’s such a strange poem for eighth graders. “It claims it’s going to be talking about poetry and prose in the title,” one student complains, “and then it’s all this stuff about birds and rain and snow.”

Tomorrow I will model the steps of interpretation, relying heavily on the questions and steps in the two texts about reading poetry they went over today, with the hope that they’ll be able to do it for themselves, at some point.

Reading

Autumn Sunday in the Yard

The Boy and a Soccer Ball

Natural Consequences

A kid shoots a paper wad at the trash can and misses I sit and look at him, at the wad of paper on the floor, back to him — what’s a logical, natural consequence? There really isn’t a natural consequence, I guess, but a logical one? A negative reinforcer? Or even a punishment?

I hate moments like this. I find myself being far more analytical in situations than I really need to be.

New Friends

M-Jezzy

Dear Terrence,

Seven years ago, on 13 October 2006, I wrote this, I worked at a day treatment facility for kids who had been unable to find a path to success in school.

Yesterday, one of the boys in our program asked if he could use the computer for a little while. “No problem,” I said. He’s had a great week, and it was a slow morning.

The week was much improved over the past. We were both frustrated about how things were going in my class – he much more than I. At the end of the last six weeks, when we were working on science (now we’ve switched to social studies for the second six weeks), M-Jezzy (his nom de plume at our program’s blog) was trying to make up some missed work, and getting very frustrated about it.

“Man, I just hate science,” he exclaimed.

“That’s fine,” I said. “Not everyone likes science. What we can do, though, is use that as a way to make up some of your work.” I instructed him to log into our blog, akacoolpeople.com, and write about science and why he hates it. “Explain three reasons you don’t like it, and we’ll count that as one of your missed assignments.”

He wrote,

I do not like science at all. And i,ve got three reasons why. One reason is because it is so confusing. likewhe gives the homework out. I dont know what he is talking about beause. They would be so many things that he is talking about. An the other reason iswhen he gives the i want know what to do because. It will be so many things that you would have to look for an you would have to do so much research. And the last reason is the things that he teaches in class i dont know wat in the world that hebe talking about. Likewe was talking about an atom an what i have to study about it is so hard because. The atom has so many things in it. And you will get mixed up with all the parts of an atom. Beceause you will not know how to put them in oder. An if you get this and you are really feeling wat i am saying to you then mail me back M-JEZZY out. I hate science so bad i wish i did not have it at all. (science)

I read it and thought, “What an indictment of me. I obviously don’t explain things for him, and I can’t even make myself clear when assigning homework.”

Depressing.

But fixable.

I talked to the head teacher about it; I talked to the program director about it; I talked to the head counselor about it. The consensus: M-Jezzy does not deal with ambiguity well (as if anyone really does). Like most people, he wants to know where he’s going and what he’s going to have to do to get there.

Starting this week, I began something new. Something obvious. Something basic. Something I should have been doing all along. I blocked off a portion of the white-board and wrote an outline of what we’d be doing, including information about what kind of activity it would be.

Next class, M-Jeezy was like a different young man – much more attentive, much more focused, much more involved. He asked penetrating questions, and he didn’t giggle too much.

A success, I thought.

Back to yesterday morning. M-Jezzy sits down at the computer and logs into “aka cool people,” and starts typing. This is what he writes:

now sence my teacher was started to put the agenda on the board i am starting to learn more in class and i know no wat to do.And i am not getting confused write me

I can’t remember the last time I felt so good.

Yet it was not what M-Jezzy wrote that made my day – it was that he did it spontaneously.

M-Jezzy was fifteen when I wrote this, theoretically a tenth-grader but he was still in eighth grade because of behavior. He’d been tossed out of regular school because of his behavior — basically an unwillingness to regulate his impulses in any way whatsoever — and then tossed out of alternative school for the same reason. All of this left him with few alternatives, which is how he landed in our day treatment facility — a last ditch effort to teach him the social and personal skills he so clearly lacked and so desperately needed.

In the end, it’s clear that we didn’t get through to M-Jezzy, for later this week, he’ll be going to trial facing six charges: misdemeanors and two felonies. The former: trespass charges and assault on a female; the latter: first degree murder and intentional child abuse with serious physical injury. He stands accused of beating to death his girlfriend’s four-year-old son.

From the accounts I’ve read in newspapers, it seems a reasonable assumption that he’s guilty. Knowing him personally and seeing his temper in action, I find it tragically plausible that he did indeed beat a toddler to death.

The vindictive (read: human) side of me thinks his punishment should be based on a simple mathematical equation. A proportion, really. Take the pounds per square inch of his punch over the weight of the child he beat to death. The other side of the proportion you can probably figure out: x over his weight. Solve for X. Then he should be beaten regularly by someone who can hit with that much force. Beaten for weeks on end. Months on end. The end will come — eventually, he’ll be beaten to death in one, long session. But he’ll never know which one it will be. So each time he sees his executioner, he’ll have to ask himself the same question his victim asked himself: how will it end this time?

Fortunately, I’m not in charge of sentencing. The compassionate side of me realizes that such punishment is cruel, but again, the vindictive side says, “Who is he to deserve mercy?” It’s a conundrum.

I write this to you because I want to be perfectly clear with you: I don’t know how M-Jezzy got from where he was merely a disruptive kid in an under-funded day treatment facility to a young man facing serious prison time (if he survives: my aunt, who worked in the prison system for twenty years, assures me that as soon as inmates find out what M-Jezzy got convicted of, if he’s convicted, they’ll take care of the problem). I don’t know the road he took, but I do know this: you remind me of him so much sometimes it’s terrifying. And now, it should be terrifying for you.

With concern,

Your Teacher

Polish Picnic 2013

Saturday Soccer

It’s been a tough soccer season, the mirror image of last year’s spectacular season. We’ve had some tough losses this year, and the only win thus far came last week, when L was home with a bad cough.

This week, she’s back, playing all positions: goalie, defender, mid-fielder, forward.

The irony of that statement is that she often played all those positions at the same time — all the kids do. A sort of herd soccer. They’re beginning to learn about positional play, but they get excited, each and every one of them, and soon, there’s a little herd of green and blue jerseys, all attacking the ball.

Today, there is such hope: we are up one-nil for the first quarter. The green team equalizes, in a sense: one of our players shoots into his own goal trying to clear the ball. Soon, though, we’re up three one.

And then comes the barrage of little number five on the green team: a little blond girl shorter and faster than everyone else on the field, with phenomenal ball control. She shoots one, two, three goals within five minutes.

So we lose, five three. Well, four three. One doesn’t count. But of course it does. But of course, it doesn’t.

Debussy

Positive and Negative

Dear Teresa,

When I asked you today to keep track of your positive comments and negative comments throughout the day, I didn’t really realize you might not be able to tell the difference. I realized this when I saw in the positive column, “Please get out of my face.”

Despite what you’ve been told, “please” doesn’t always make all the difference in the world.

With a smile,

Your Teacher

Common Core

The rumbling in the district probably started long before I first started hearing about coming “new standards.” We’d just revised the state standards a few years earlier, but I’d begun teaching in the state the year the new standards went into effect, so I never had to go back and revamp plans to correspond with new standards.

The rumbling in the district probably started long before I first started hearing about coming “new standards.” We’d just revised the state standards a few years earlier, but I’d begun teaching in the state the year the new standards went into effect, so I never had to go back and revamp plans to correspond with new standards.

“Well, I guess I’ll see what that’s like now,” was my only real concern. But I was confused: I knew little about what these “new standards” might be or whence they might come. I assumed it was the state again, fiddling eternally with the numbered guidelines that are my daily metric of effectiveness.

Last year, though, we began going through the process of shifting from old state standards to the Common Core. This meant, it turned out, decidedly more than changing standard numbers on our lesson plans. The head of English instruction in our district, in a series of workshops preparing teachers for the change, constant told us (and more importantly, showed us) how these standards would necessitate a change not only in what we teach but also in how we teach.

I did have some initial concerns over the standards, though. The English standards place high importance on what in Common Core nomenclature is known as “informational texts.” We used just to call it “nonfiction,” but somehow that’s not descriptive enough, I suppose. This is not nonfiction as in essays and biographies, though. By one definition,

informational text is:

- text whose primary purpose is to convey information about the natural and social world.

- text that typically has characteristic features such as addressing whole classes of things in a timeless way.

- text that comes in many different formats, including books, magazines, handouts, brochures, CD-ROMs, and the Internet

This includes, then, things like textbooks, pamphlets, forms, and myriad other textual forms. I’m certainly not going to suggest these things have no place in a classroom; indeed, they’re critical in the classroom. But what proportion? The Common Core suggests that by high school, students should be reading seventy percent informational texts. This means, in short, the classics are essentially gone. Only thirty percent of high school students’ reading should be fiction, and I’ve heard from a friend who is also a teacher that her principal has informed the librarian that she will receive absolutely no funding for the purchase of fiction this year.

What’s the thinking behind this? The earlier-quoted article continues by providing four reasons why these texts are so important:

we feel children should encounter more informational text in the primary grades for the reasons explained below:

- Informational text is key to success in later schooling.

- Informational text is ubiquitous in society.

- Informational text is preferred reading material for some children.

- Informational text often addresses children’s interests and questions.

It’s all a question of supposedly getting kids ready for “the real world,” where most of the texts they read are informational texts. Indeed, the first point echoes things I’ve heard in my own district about informational texts: students get to college and have difficulty reading college textbooks. They’re used to reading primarily fiction, goes the argument. This is simply ridiculous, most conspicuously for the stunningly obvious fact that high schools use textbooks, which ironically is a function of the second point about the ubiquity of informational texts.

Beyond that, though, it belies the my experience and that of everyone else I know who successfully completed college: we all made the shift from (supposedly) primarily fiction reading to mostly nonfictional texts without much difficulty. There is some truth to the claim that much of informational text in the world is argument, written to persuade, but all middle and high school curricula covered that without Common Core’s insistence on seventy-percent informational text coverage.

Yet other portions of the Common Core struck me as reasonable, even necessary. For instance, the CCS places a much higher premium on writing than other standards, and the proposed shift in assessment (via Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium) seemed more like things people do in “real life” rather than simply choosing A, B, C, or D. It involves reading resources with the aim of synthesizing something from them (often an argument). People do that all the time in their jobs, and it’s a critical skill.

I’m ashamed to admit that I never stopped to think about what political forces might have lined up behind these new standards. Somewhat like Milgram’s thirty-seven, I just did what I was told. I heard the hoopla, went to the meetings, studied the new standards, and went along with it, changing my unit plans, ditching this and that, adding that and this. Yet the more I learn about it, the more concerned I am.

The major concern right-leaning people have about the Common Core has to do with the apparent increased control it gives the federal government over education. Yet that seems to be a misplaced concern. Yet I am worried about the loss of state control over education, not to the federal government but to the private corporations that make the tests that will assess students’ and teachers’ performance with the new standards. It is, as one commentator called it, “Education without Representation.”

Another worry: we’re going headlong into these new standards and tests with very little empirical testing. All these states just seem to be jumping on the bandwagon and saying, “Hey, great idea — let’s do it!” But will these standards actually accomplish what they’re touted to accomplish? In modern education, it’s all a question of data, data, data — except in this case.

A final worry is the one that likely rolled around in the thoughts of all teachers who have spent more than a couple of years in the classroom. Educational fads come and go. Standards change and then disappear, reappear, and are reshaped. My fear is that this too will only turn out to be a fad, something that everyone gets excited palpitations about now but only appears in the footnotes of Intro to Ed books. If that is the case, a final, more politically conservative concern: think of all the tax dollars wasted in that case in this clamoring toward these new supposedly salvific standards. We could likely do some real good in the classroom for all that money.