What’s New in Lipnica?

“What’s new in Lipnica?” I asked when I arrived in Lipnica in 2000. And again today, the same question. J, my closest friend from Lipnica, arrived in the early evening and gave the same response to the same question.

We first headed to the border crossing that was just past Lipnica. No border crossing anymore. Thanks to the EU, no border anymore. But that would not be quite right: Slovakia uses the Euro, Poland doesn’t. This means a change in border crossings: in the 1990s, Poles went to Slovakia for cheap goods; these days, the reverse is much more common.

On through the lower part of Lipnica to the Elementary School Number 1.

Where I see the first surprise: a new sports complex.

And further down the road, a few more surprises: street lights with solar panels and wind turbines.

All the while, a new road, a road that doesn’t jostle riders to dust.

Not all surprises are plesant.

And not all sights are surprises.

What’s changed in Lipnica? Everything, and nothing.

Thursday at Dudek

Fourteen years — a long time to wait. One could move to another continent, start a life in an American city, move back to the original continent, start life there again, get married, move back again to the other continent, have a child, buy a house, have another child, and a thousand other things in that time. And when there are two involved, the possibilities are even more endless: new businesses, new houses, and more. The children I just finished teaching were born fourteen years ago. Their whole lives are encapsulated in those fourteen years, and for us adults, in reality, fourteen years is ironically almost nothing when casting a backwards glance in time.

A Thursday night fourteen years ago would have often meant only one thing: an evening of billiards and conversation at Dudek (“Woodpecker”), a bar and music room in Nowy Targ. C, the only other American I knew for several kilometers, and I would head out around seven, have something to eat (the owner of the bar fixes the most amazing hamburgers on the planet), then head to the pool table for an evening of nine-ball. We’d flirt a little with the ladies, chat with friends, and be your fairly typical single guys on a night out.

Fourteen years later, we decided it was time to head back. But how times have changed. Both married, both fathers, both with countless other concerns (the cost of heating oil; the potential water damage done during a recent downpour; the health of our children; myriad other worries) than having a good time on a Thursday evening.

But last night, we put all those concerns behind us for a few hours and acted like it was 1999 — literally — again.

We began in the backyard: drinks, cigars, conversation. C’s son, F, regaled us with magic tricks; C, his wife M, and I talked about differences between life in the States and in Poland; and a couple of hours slipped by almost unnoticed.

We headed off down the hill, between the hospital and cemetery (the ironies), stopping momentarily to look at the views. At any rate I stopped and C slowed: the views are almost commonplace for C now, and if the Tatra Mountains aren’t crystal clear, well, there’s not much point in slowing to look. They’ll be clearer tomorrow, or the day after.

Down, down, through a small neighborhood, across the river, and suddenly, there we were,

just a couple of blocks from the town square. And how the rynek has changed. I was honestly too much in awe about the changes to think of taking a picture. Or maybe I just want to save that for some other time.

Yet the tragic highlight of the walk to the club was the construction occurring at what used to be the bus station in Nowy Targ. It was a perfect example of sixties archetecture in Poland.

Now, in its place, they are building a gallery. Why not just renovate? Why throw away a piece of history?

“Perhaps they want to forget about it,” C suggested. Perhaps. Maybe I’m just being overly Romantic about it.

But last night was not the time for wallowing in the past. Well, perhaps it was — after all, we left the site of the old bus station and arrived shortly at our old haunt, and as we walked, almost every sentence began with “Remember when…?”.

We arrived at the fenced outdoor sitting area only to find the gate locked. There were a few people sitting at the tables there, but the gate was locked up tight. And suddenly, from the bar, the owner, G, rushed out to greet us. A burly man in every sense of the word, G had always been kind to us when we were passing seemingly countless hours in his establishment. Sometimes he would bring us free food; sometimes he would bring us free drinks; sometimes he would declare that our five hours of nine-ball that evening were “on the house.”

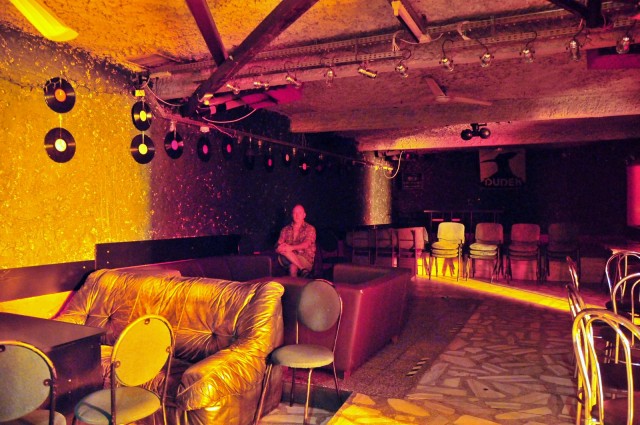

It was good to be back, especially when we discovered that, like the bus station, Dudek has, for all intents and purposes, passed into shadow. There are no more concerts; the bar is closed except for patrations of the hotel above it. “But you guys come on in!” he declared. He opened the upper room for us to shoot pool, and fourteen years disappeared, and it was 1999 again.

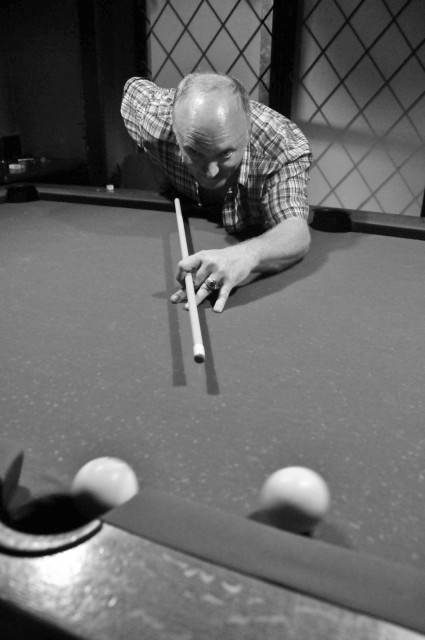

We played pool,

we wandered back into the virtually pitch black concert area, and we reminisced endlessly.

The hours slipped by and before either of us expected it, it was two thirty in the morning. Just like old times. We went down to the main bar area to find we were the only ones in the whole place. G had sat there, putting CD after CD on, keeping us fed and watered, and letting us revel in the last time we’ll ever get to relive those magical years of the late 1990’s.

G called us a taxi, and we chatted one last time.

“In fact, I’m trying to sell the place,” G admits just before we leave.

I know better than to try to capture the long-gone past. I’ve tried it before, and it didn’t work. Still, a thought flashed as G admitted his hopes to sell the place.

“How much would you want for the place? Maybe C and I could go into business together…”

Style

Camouflage shorts and shirt in contrasting pattern. Ankle-high socks with leather sandals. Graying hair in a pompadour. Man-purse. Shopping for tractor parts in the flea market.

Welcome to Central Europe.

New Market Memories

The 9:18 bus is the only option. There is one at 12:40, but with the return schedule as it is, that leaves only an hour or so to finish one’s business in town. No, the 9:18 is and always has been my Saturday choice. It gives me enough time to purchase the items I need, have a bite of lunch, and possibly wander around town a bit, maybe head to one of the old churches to sit and think.

The bus trip lasts about an hour and costs five zloty, though when I first arrived in Poland, it was less than four. We roll through Jablonka, Piekielnik, Czarny Dunajec, Rogoznik, Ludzmierz. Between Piekielnik and Czarny Dunajec are vast fields where local farmers grow potatoes, grains, beets — everything. There are more between Czarny Dunajec — the halfway point — and Ludzmierz.

We bounce and sway on the uneven, hole-filled Polish roads, finally arriving at the bus station at almost eleven.

I’m here for a new sport jacket — the Polish equivalent of the prom is coming up in a couple of weeks, and while I don’t have enough money for a suit, I thought I’d splurge a little and buy a new sports jacket. Without a suit, I’ll almost certainly be the most informally dressed person at the dance, but I’ve learned to accept being just a little different.

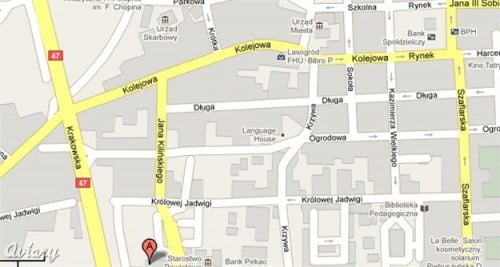

I head out of the station, down Krolowej Jadwigi Street, turn left Krzywa (“Crooked”) Street, then right Dluga (“Long”) Street after stopping at the corner of Kzywa and Ogrodowa to buy a little snack, maybe a sourkraut croquette.

It’s winter, so there’s snow and ice everywhere. Even the sidewalks have a thick layer of tramped down snow that has turned to ice.

There’s an art to walking on ice, and after a couple of winters in Poland, I think I’ve mastered it. Still, I slip and slide enough to seek out the few spots of pavement that might appear. The two or three steps with good traction is a calming moment: I never realize how my whole body tenses up as I walk about on ice until I take two or three steps on asphalt or concrete. My back loosens up, my shoulders drop, my toes uncurl, and for a brief moment, walking is pleasurable again.

I stop at a couple of shops, find something acceptable, then head to the pizzeria at the corner of the town square for some warmth and food.

Once inside, I unwrap the many layers I have on, order a coffee, and thumb through whatever book I have in my backpack. Experience has taught me never to leave my little apartment without adequate reading material, a change of underwear, and some extra cash.

The waitress brings me my coffee, and I order my pizza, twice making sure she realizes that I most definitely do not want ketchup on my pizza. An odd habit, and one that I’ve never acclimated to. At the same time, Polish ketchup is better than American: slightly spicy and a little tangy, it goes better with fries than the sweet American alternative. Still, ketchup is ketchup, pizza is pizza, and never should the two meet, in my American mind.

The cook takes a little longer than I’d anticipated on my pizza, and it quickly becomes evident that I won’t be taking the 13:40 bus back home. And so I suddenly find myself with two additional hours.

I think about heading to the old church behind the rynek. There’s a garden in the back with an elaborate Way of the Cross.

Essentially, the whole New Testament is laid out in small, glass-enclosed dioramas.

It’s a little kitschy, but there’s something about it I enjoy. I’ve never seen it in the snow, and it might make for some interesting contrast.

In the end, I decide to take a chance and drop in on the Peace Corps volunteer who lives in Nowy Targ. He’s not expecting me, but he often isn’t.

I make the long trek to his apartment, almost literally on the other side of town. I walk forever along Aleja Tysiaclecia (“Thousand-Year Avenue”), which turns into Kolejowa (“Railway”) Street before changing names again to ulica Ludzmierska (“Ludzmierz Street”) until I reach the Bor neighborhood.

He’s home, and as always, gracious and kind.

“I’ve got a couple of hours till my bus,” I explain, though I know it’s not necessary. I virtually live here just about every other weekend, filling Friday nights with nine-ball, libation, and English conversation.

We sit and watch ski jumping on a German sports channel — he speaks German, I don’t, so I just watch the footage and imagine my own commentary.

At about fifteen past three, I head out for my bus, once again curling my toes and drawing up my shoulders to walk out on the ice.

Such was an average Saturday when I lived in Lipnica in the late 1990s. This evening, I’ll be heading back to Nowy Targ for another evening of billards and conversation — the first such in about fourteen years, I guess. I’ll see how things have changed in NT, but already, there are differences: I’ll be driving instead of taking the bus. (Indeed, I’ve heard that PKP Nowy Targ has gone completely out of business, so there is no 9:18 or 12:40 bus anymore. It’s all private bus-lettes now, and I don’t have the slightest idea about their schedule.) More changes: said friend, C, still lives in NT, but married with a house now, he lives quite a distance from his original Bor neighborhood. This of course doesn’t take into account all the other changes swirling around us, most important being that we’re both fathers now.

But I expect we’ll walk into Dudek, greet the bartender (I’ll bet it’s the same fellow.) and suddenly, for a few hours, it will be 1998 again.

Her Own Money

Jarmark

Dress shoes, curtains, cosmetics, pig intestines, wrist watches, toys, paintings, binders, nails, cigarettes, t+shirts, pens, hatchets, bras, cookies, hammers, cloth, suits ducks, hand-carved decorations, wiring, pots, chairs, sandals, strawberries, hats, metal detectors, potatoes, toilet plungers,house shoes, sickles, blinds, perfumes, hiking boots, mufflers, pocket watches, panties, puzzles, pans, pipes, scopes, cherries, hedge trimmers, cutlery sets, skateboards, lawn mowers, porch swings, DVDs, planers, tables, knife sharpeners, spoons, screw drivers, CDs, hair brushes, power outlets, hair driers, chickens, Croc rip-offs, faucets, pencils, stomach lining, Teva rip-offs, rake handles, hiking poles, plums, Nike-rip-offs, wrench sets, geese, bikes, tobacco, ties, pencil bags, homemade cheese, levels, skis, pigeons, tank-tops, forks, nuts, tennis shoes, pigs, binoculars, hunting knives, socks, butter knives, rakes, carving knives, fillet knives, Russian cameras, notebooks, axes, inline skates, cats, insulation, pencils, e-cigarettes, tiles, bolts, dresses, light switches, high heels, instant coffee, dogs, shovel heads, baseball caps, chains and stakes for grazing cows, and countless other items, all available at your local jarmark.

Polish Ketchup

Disrepair

The signs of it are everywhere: houses with roofs that have long-since lost the luster of their newness.

Barns collapse on themselves.

Road repairs, melting in the heat of an unusually warm day, prove themselves to be only temporary.

When I first arrived in Poland in 1996, sights like these were common everywhere, in the countryside and in the capital. In 2013, such scenes are less common.

The Visit

“J, are you here?” She somehow knocks at the door, opens the door, enters the house, and says this all at the same time. It took me a long time to grow accustomed to this style of entering a friend’s house, but she’s lived in Orawa all her life, and it comes naturally to her.

I walk to the door as she enters and asks, “Is Pani J here?”

“No, she went to the store a few minutes ago,” I explain. “She should be back shortly.” I usher her into the kitchen, recommending that she wait here. Then again, Babcia has a gift for coming back home, sneaking into the house, and disappearing upstairs to iron this or to clean that, so I suggest that perhaps she’s upstairs. “I’ll just check.”

I head to the base of the stairs–those countless stairs that lead to a floor of rooms for guests of the bed and breakfast and then to the next floor where the family residences are and finally to more guest rooms on the floor above–and call, “Babcia!” The name echoes through the tiled stairway and dies without response.

“I guess she’s not here,” I explain heading back to the kitchen.

“J is too young to have a grandchild your age. You’re calling her ‘grandmother’ because…”

“Because my daughter calls her that,” I explain.

“Oh! You’re K’s husband! Oh, okay, okay. You know, I was K’s teacher.”

We chat for a little about K, about E and L, about roads in Poland (why does that topic always seem to come up? Every Pole summarizes the situation with the same words: “holes within holes.”) and suddenly, there’s Babcia.

“I hear voices!” she sings as she enters. She’s always glad to have visitors, and she’s particularly glad to see M, her close friend.

“What shall I make for you? Coffee? Tea?”

Before long, they’re drinking coffee and talking about who’s gotten married, how M’s mother, who just turned a mind-blowing 99 years old in May, is doing, about their children, their grandchildren, the neighbors, politics, films.

Yet the conversation always seems to turn back to something we might call in English gossip but in Polish sounds somehow different. It’s not just that the word somehow is different. The word for “gossip” in Polish (plotkować) traces its etymology directly to the word for “fence” (płot), for that’s where it traditionally takes place. No, it’s not that the word sounds different–of course it would, as it’s a different language.

It’s the act itself that sounds different. All gossip here eventually turns back to a personal connection, and while malicious gossip certainly does take place, the vast majority of it sounds more like a cross between a local newscast and spoken memoirs. The gossip can reach back years and years, to people they knew decades ago, to events that have long passed from the common memory.

And so the two babcias sit at the kitchen table, swimming in the past, present, and future simultaneously.

Shop

First Day at (Polish) School

It’s L’s first day at a Polish school, picking up with the kindergarten kids for their final two weeks of school. She was upset the night before: “I don’t want to go!” was a common tearful refrain. “I don’t want to go” are the first words out of her mouth this morning. But a little bribery works wonders: “After school, we’ll stop in at Steskal’s for an ice cream cone, and later today, we’ll go visit a toy store.”

And so off we go, heading through the fields to school — another “only in rural Poland” moment.

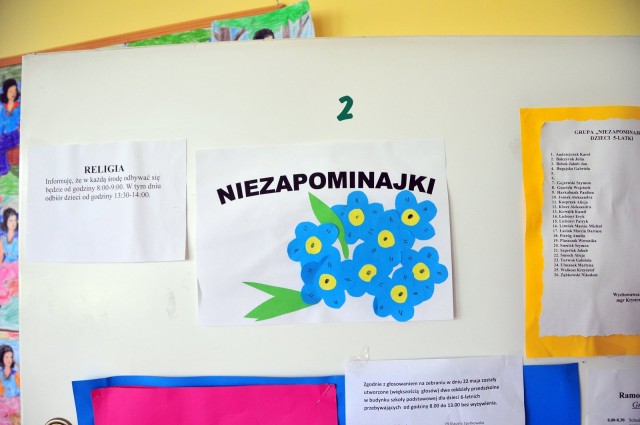

We meet with the director (not, it turns out, my former student, which is odd: I had two students with the exact same name, and now this makes the third female in this small area with the same first and last name), and she leads us to L’s teacher. Each class is given a name like “Bumble Bees” and “Dragons” and this and that: a real mix of names. L has joined the “Forget-Me-Nots”.

It’s a colorful room with an original bit of decoration in the middle.

The first few minutes she’s very clingy. She doesn’t want to participate; she doesn’t want to speak; she doesn’t even want to show her face, literally. I coax her to a table of girls, and I begin chatting with them, hoping L will join in. They all introduce themselves, we talk a bit, and slowly L begins to come out of her shell. She eventually asks for a copy of the work the children are completing.

Before long, the kids circle up, sitting “Turkish style” (a direct translation of the Polish equivalent of criss-cross-applesauce). Then there are games, marching, chanting, singing, generally silliness. L takes part, somewhat reluctantly.

Soon it’s time for the “second breakfast” (i.e., snack), and as the children are washing up, the teacher tells me that after snack, they’re going to be the next in line to go out and look at the firetruck that has been sitting in front of the school most of the morning — sort of a guided tour of a firefighter’s world.

As we head out, another “rural Polska” moment, for we have to wait as an elderly dziadek drives his equally old tractor down the street, a tractor so old with such a weak engine that it has difficulty going over the speed bump. The driver has to throw it in reverse, getting up a little more momentum the second time, to roll over the bump.

We cross the street and the presentation begins. The firefighters show the kids their oxygen masks, their aspirators, their hoses, their helmets — in a word, everything.

Afterward, we all head back inside for the latest installment of Cała Polska Czyta Dzieciom — All of Poland Reads to Its Children, roughly translated. Representatives of various professions have been coming to the school to read to the children, and today, it was a police officer’s turn.

Of course all the children are interested in one thing, and one thing only: the officer’s pistol. The officer take the clip from the gun, gives it a tug to release any shell that might already be chambered, then holds it up for everyone to see. Since Poland, like most of Europe, has very strict limits on citizens’ gun ownership rights (in short, there are none), most of these children have never seen a pistol in person (except on the belt of a police officer). It’s a nine millimeter with a six-bullet magazine, the officer explains, and there’s significant “Ooo’ing” and “Ahh’ing.” I find myself thinking that had this happened in the States, some kid in the group would have raised his hand to explain that someone in his family has a nine millimeter with a seventeen-bullet magazine.

But we’re not in the States, and the gun produces the intended reaction, and as the children exit the room, the story has disappeared into a fog of chatting about the pistol, especially among the boys.

But L has other things on her mind: there’s a picture that’s still only partially colored.

After school, as we walk with ice cream cones to the roar of tractor trailer trucks heading to Slovakia (“This is an international throughway now,” Babcia has explained more than once), we talk about the day. L decides tomorrow she can stay a little longer, then Wednesday, the whole day. Provided we go to the flea market first.

She’s turning Polish faster than I thought possible.

Afternoon Walk 2

The weekend winds down. The cousins head back to the outskirts of Krakow after one quick game of intercontinental family soccer. It’s a version of the game that might not be immediately recognized: incredibly wide goals, lax rules, multi-positional players, and a total goal total that’s close to forty.

Once it’s just the three of us again — Babcia, L, and I — Babcia asks us to take the dog out for a walk. He’s a friendly fellow, fairly curious yet fairly obedient, so walks usually involve him running ahead, trailing behind darting off to the left or right only to come almost immediately when someone calls, “Kajtus!”

This afternoon, though we start of in the same direction, passing the same barn next to Babcia’s with the same ducks marching by the same trailer,

we take a right instead of a left, and soon we’re in the empty flea market. Stall after covered stall, one beside the next, all leading to the main market area where even more stand waiting. This market has been in this same location for only about twenty-five years, but the market itself dates to the time of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

“What about during the Communist period?” I ask Babcia. Would such blatantly privatized ventures have been allowed?

“Of course! In many ways, it was more important then than now.”

The ironies of Poland: in many ways Communist for decades, in many other ways, breaking the mold of Communism — which in turn broke Communism. For instance, there were never the large collective farms in Poland that one saw in Stalinist Soviet Union. The State did not crack down on religious expression as it did in the Soviet Union. These two facts alone did more to undermine Communism and help with the post-Communist restructuring than almost anything else.

The ironies of Poland.

Our walk continues through the market to a point where we meet the ubiquitous river — even when we’re not walking to it, we’re walking to it. And so are many others.

We turn and walk along the river, and the scene becomes almost fairy-tale-like. More ironies of Poland: within a mere few meters of the local bastion of commerce and capitalism, so to speak, one can find land that seems almost untouched by anyone.

L perches herself on a tree, and for a few moments, we just look around. The light is golden now, filtering through the leaves and reflecting here and there on the water.

After dinner at a local restaurant — the first real restaurant in Jablonka — L and I head out for another walk. The air is cool, the Tatra Mountains are unusually clear, and the light is only getting richer and richer.

making everything positively glow.

Eventually we make it back to our usual riverside retreat. A man is fishing there, a man who turns to look at me and smile his crooked smile and make himself immediately recognizable.

“Pawel!”

“Dobry wieczor, Pan.”

I haven’t taught him in probably a decade; we’re both adults now, and he’s likely in his thirties, but he still calls me “Pan,” the respectful third-person form children use with adults and strangers use with each other. K still talks to her teachers the same way when she meets them. In fact, everyone does. It’s just part of the culture. Still, it would be nice for him to see us now as equals. Then again, probably he does: linguistic formality doesn’t always mirror personal opinion.

It’s something to accept and move on, like so many things in life. It’s a trifling matter after all. And views like this make sure we keep those trifles in perspective.

From a Window

Ognisko

A simple concept: some wood, some sausage, a match or two, a loaf of bread, something to drink, someone to share it all with. Put it all together, though, and it somehow becomes more than the sum of its parts. Add the laughter of children and it becomes positively magical. The conversation winds through topic after topic as the sausage begins to sizzle, and as the sun sets and everyone pats their bellies, literally or figuratively, one gets an almost divine feeling.

“And we looked out over the sausage and steaming tea, heard the laughter and watched the glowing embers and dimming sun, and lo, it was good.”

Busy Day

Busy, busy, busy day. And this is only about one-third of it.

Paradise Unseen

They sit around the fire, complete darkness surrounding them, the only sounds the crackling fire and the occasional truck passing on the nearest road (still a mile away). They sit passing around a shot glass and bottle of vodka. The chaser, a can of beer for each, a cigarette in the other hand. Some talk of escape, of getting the hell out of this little f-ing village. They talk of going abroad, of returning with an Audi, of making it big. Some will escape, if “escape” is even the proper word. Some will return with with an Audi, though used.

Who will look around them, at the bark of pines glowing in the firelight, at the embers and sparks as they pop and rise into the jet-black night, joining the stars and the mysteries around them, and realize that they already have all that they really need? Who will look into others’ faces, listen to their girlfriend’s laughter, smell the magic of smoke in a hay-flavored summer sky and realize that what they have, others would kill or die for–and in fact already have?

Breakfast

Unfinished

Certainly not a strictly-Polish phenomenon: the occupied yet unfinished home. (Not the best example, but this house has had an unfinished upstairs since at least 1996, when I first saw it.)

Likely a phenomenon most common in Poland: the finished yet unoccupied home.

Certainly a purely Polish phenomenon: the two houses side by side.