Camouflage shorts and shirt in contrasting pattern. Ankle-high socks with leather sandals. Graying hair in a pompadour. Man-purse. Shopping for tractor parts in the flea market.

Welcome to Central Europe.

Camouflage shorts and shirt in contrasting pattern. Ankle-high socks with leather sandals. Graying hair in a pompadour. Man-purse. Shopping for tractor parts in the flea market.

Welcome to Central Europe.

The 9:18 bus is the only option. There is one at 12:40, but with the return schedule as it is, that leaves only an hour or so to finish one’s business in town. No, the 9:18 is and always has been my Saturday choice. It gives me enough time to purchase the items I need, have a bite of lunch, and possibly wander around town a bit, maybe head to one of the old churches to sit and think.

The bus trip lasts about an hour and costs five zloty, though when I first arrived in Poland, it was less than four. We roll through Jablonka, Piekielnik, Czarny Dunajec, Rogoznik, Ludzmierz. Between Piekielnik and Czarny Dunajec are vast fields where local farmers grow potatoes, grains, beets — everything. There are more between Czarny Dunajec — the halfway point — and Ludzmierz.

We bounce and sway on the uneven, hole-filled Polish roads, finally arriving at the bus station at almost eleven.

I’m here for a new sport jacket — the Polish equivalent of the prom is coming up in a couple of weeks, and while I don’t have enough money for a suit, I thought I’d splurge a little and buy a new sports jacket. Without a suit, I’ll almost certainly be the most informally dressed person at the dance, but I’ve learned to accept being just a little different.

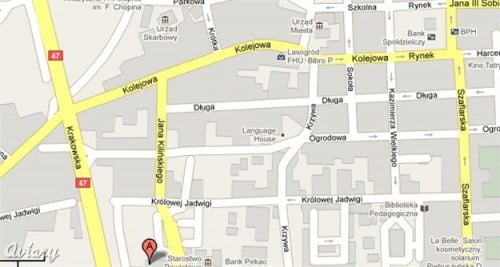

I head out of the station, down Krolowej Jadwigi Street, turn left Krzywa (“Crooked”) Street, then right Dluga (“Long”) Street after stopping at the corner of Kzywa and Ogrodowa to buy a little snack, maybe a sourkraut croquette.

It’s winter, so there’s snow and ice everywhere. Even the sidewalks have a thick layer of tramped down snow that has turned to ice.

There’s an art to walking on ice, and after a couple of winters in Poland, I think I’ve mastered it. Still, I slip and slide enough to seek out the few spots of pavement that might appear. The two or three steps with good traction is a calming moment: I never realize how my whole body tenses up as I walk about on ice until I take two or three steps on asphalt or concrete. My back loosens up, my shoulders drop, my toes uncurl, and for a brief moment, walking is pleasurable again.

I stop at a couple of shops, find something acceptable, then head to the pizzeria at the corner of the town square for some warmth and food.

Once inside, I unwrap the many layers I have on, order a coffee, and thumb through whatever book I have in my backpack. Experience has taught me never to leave my little apartment without adequate reading material, a change of underwear, and some extra cash.

The waitress brings me my coffee, and I order my pizza, twice making sure she realizes that I most definitely do not want ketchup on my pizza. An odd habit, and one that I’ve never acclimated to. At the same time, Polish ketchup is better than American: slightly spicy and a little tangy, it goes better with fries than the sweet American alternative. Still, ketchup is ketchup, pizza is pizza, and never should the two meet, in my American mind.

The cook takes a little longer than I’d anticipated on my pizza, and it quickly becomes evident that I won’t be taking the 13:40 bus back home. And so I suddenly find myself with two additional hours.

I think about heading to the old church behind the rynek. There’s a garden in the back with an elaborate Way of the Cross.

Essentially, the whole New Testament is laid out in small, glass-enclosed dioramas.

It’s a little kitschy, but there’s something about it I enjoy. I’ve never seen it in the snow, and it might make for some interesting contrast.

In the end, I decide to take a chance and drop in on the Peace Corps volunteer who lives in Nowy Targ. He’s not expecting me, but he often isn’t.

I make the long trek to his apartment, almost literally on the other side of town. I walk forever along Aleja Tysiaclecia (“Thousand-Year Avenue”), which turns into Kolejowa (“Railway”) Street before changing names again to ulica Ludzmierska (“Ludzmierz Street”) until I reach the Bor neighborhood.

He’s home, and as always, gracious and kind.

“I’ve got a couple of hours till my bus,” I explain, though I know it’s not necessary. I virtually live here just about every other weekend, filling Friday nights with nine-ball, libation, and English conversation.

We sit and watch ski jumping on a German sports channel — he speaks German, I don’t, so I just watch the footage and imagine my own commentary.

At about fifteen past three, I head out for my bus, once again curling my toes and drawing up my shoulders to walk out on the ice.

Such was an average Saturday when I lived in Lipnica in the late 1990s. This evening, I’ll be heading back to Nowy Targ for another evening of billards and conversation — the first such in about fourteen years, I guess. I’ll see how things have changed in NT, but already, there are differences: I’ll be driving instead of taking the bus. (Indeed, I’ve heard that PKP Nowy Targ has gone completely out of business, so there is no 9:18 or 12:40 bus anymore. It’s all private bus-lettes now, and I don’t have the slightest idea about their schedule.) More changes: said friend, C, still lives in NT, but married with a house now, he lives quite a distance from his original Bor neighborhood. This of course doesn’t take into account all the other changes swirling around us, most important being that we’re both fathers now.

But I expect we’ll walk into Dudek, greet the bartender (I’ll bet it’s the same fellow.) and suddenly, for a few hours, it will be 1998 again.