When I first met him, I was still learning Polish, and the intricacies of the cultural formal/informal divide largely escaped me. I knew kids referred to adults in the third person, as “Pan” or “Pani.” The fact that it applies to complete strangers as well had largely gone over my head, so I began talking to him in the second person, like we were equals and I’d known him all my life. By the time K and I married and I could legitimately speak to him in the informal second person, I’d already been doing so for almost ten years. As I got to know my father-in-law, long before I even could have imagined he would be my father-in-law, I realized that his gesture of laughing off my apology later when I realized my linguistic mistake and mentioned it was not a gesture. He probably really didn’t mind, and not just because I was an ignorant foreigner.

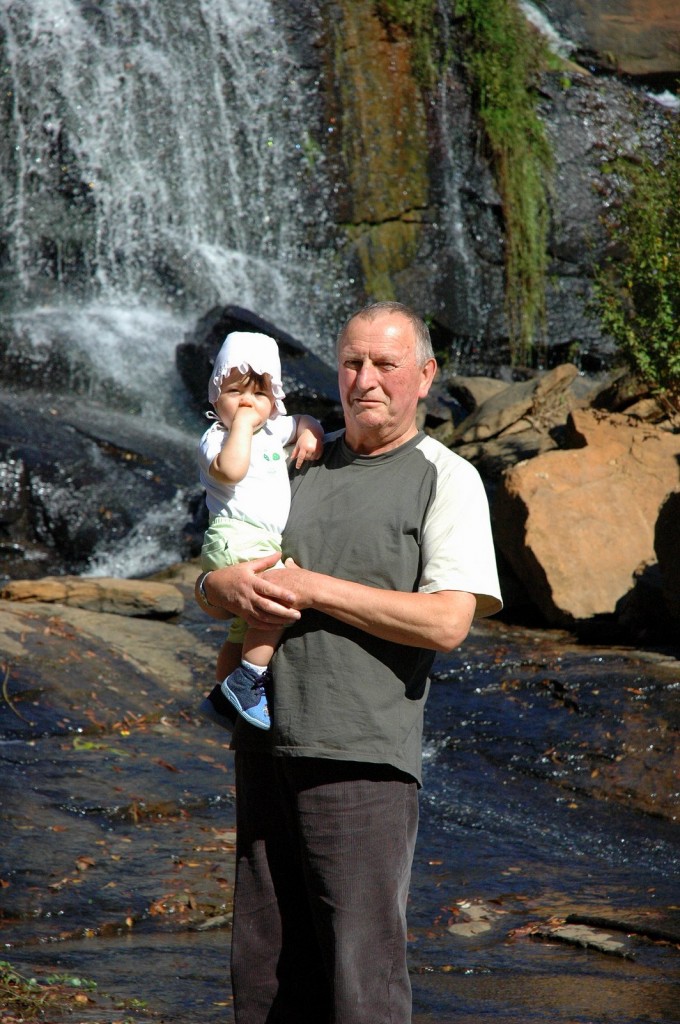

When he developed cancer some years ago, I really thought it to be little to worry about it. Perhaps it was denial; perhaps it was the understanding that, in fact, people beat cancer all the time. Two friends of mine, in fact, recently beat breast cancer. People win against cancer all the time. Of course, cancer more often than not seems to win, but Dziadek was too stubborn to let cancer best him, I rationalized. Too stubborn and too strong. As if overcoming cancer is a question of willfulness, obstinacy, and strength. If it were, it wouldn’t have had even the slightest chance of gaining even the smallest foothold with Dziadek.

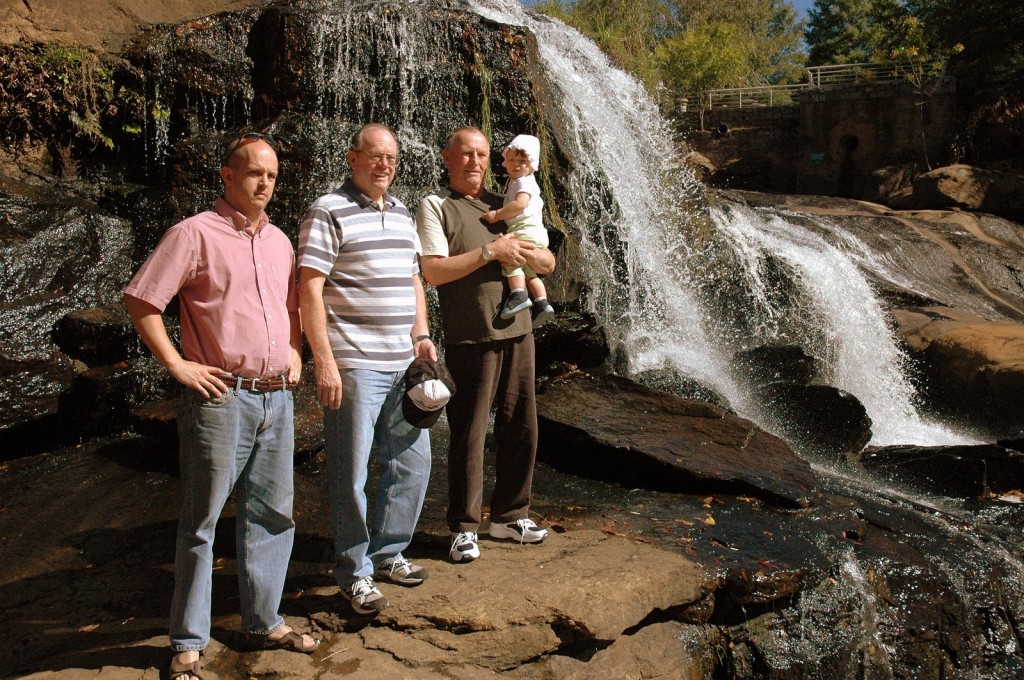

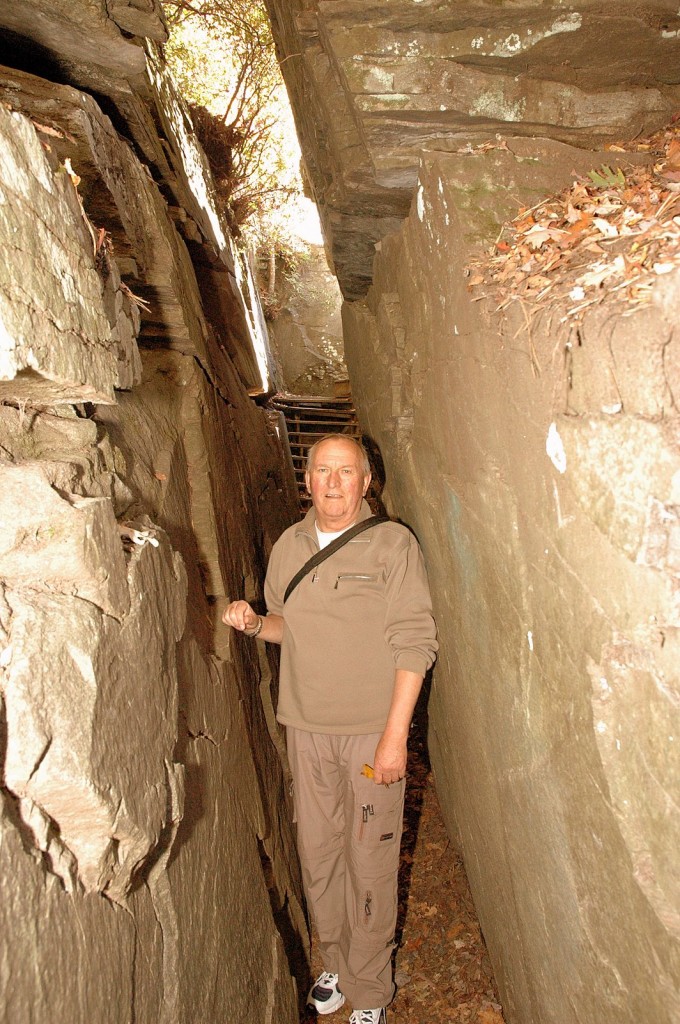

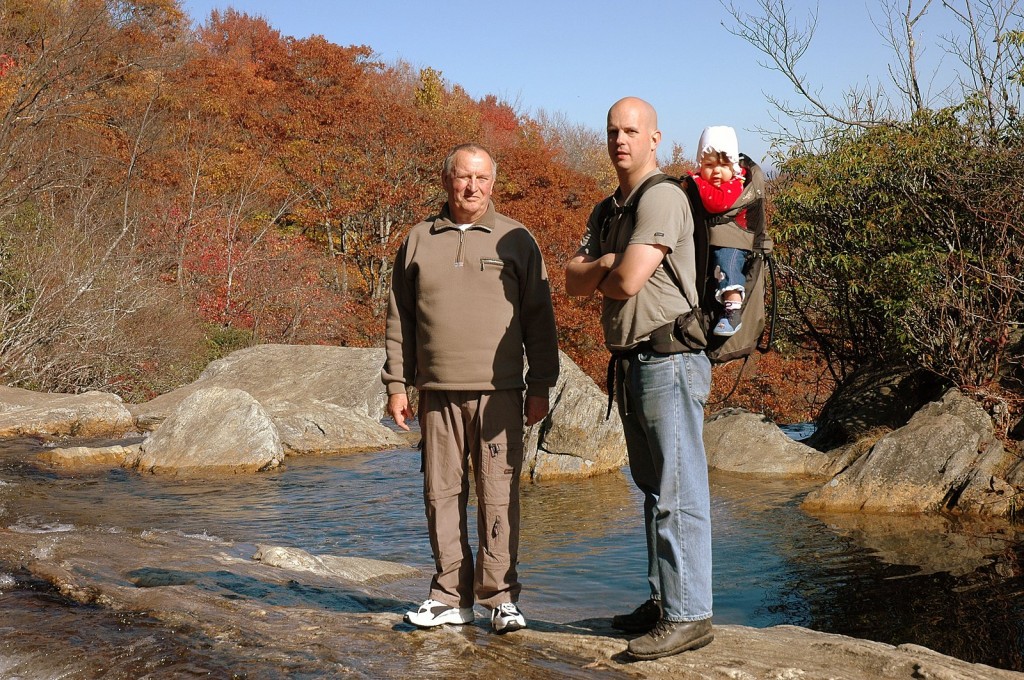

Indeed, for several years, it looked as if he and his doctors had indeed subdued it. For about five years, it was as if nothing had happened. Daily walks, guests in the bed and breakfast, weekly games of bridge, Mass every Sunday morning at 7:30, responsibilities in the village, parties when we visited — it was as if the operation, the chemo, the time in the hospital had never happened. He still got up ridiculously early every day to stoke the fires in two furnaces for guests, and when we were visiting, he was usually taking his morning coffee break when I stumbled downstairs in the morning.

The thought of heading to Poland this summer and not have him in the morning poking at me about how long I’d slept the night before — anything past about six thirty was a waste — makes the visit, on this side, still more than a month off, seem hollow. So much will be missing.

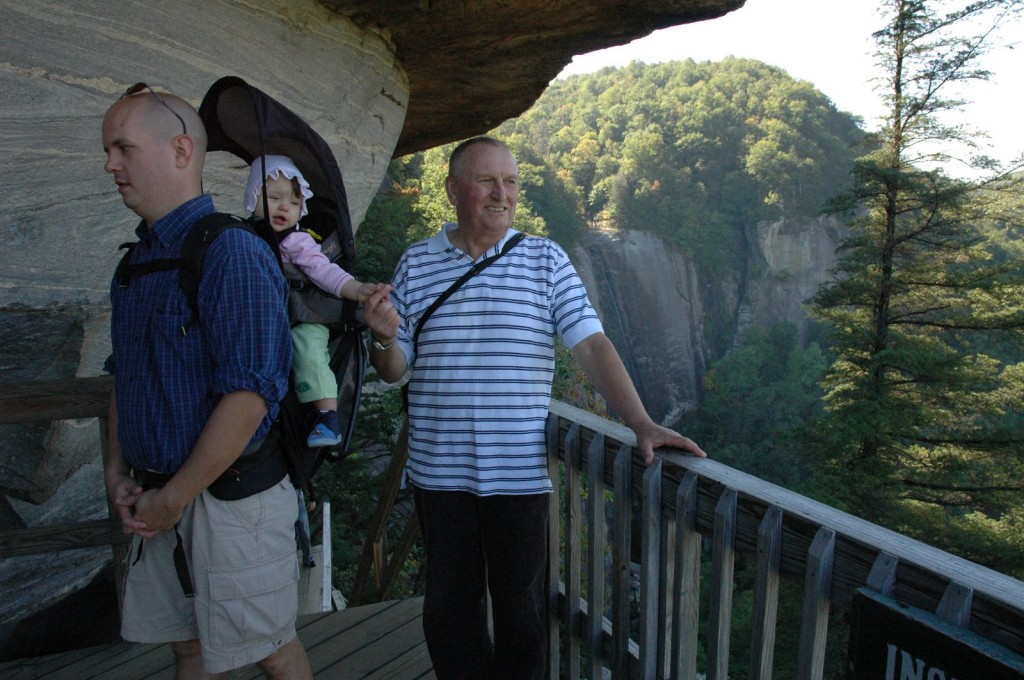

When it returned, the cancer struck his leg and quickly robbed him of one of his daily traditions, something K and I picked up as well during our visits there — indeed, while we still lived in Poland and went for family visits. A quick turn to the left at the end of a short paved road, a hundred meters to the next road, a rutted dirt road, and a right turn and within a few hundred meters, one is in the midst of hay, potato, and beet fields. “Idę na spacer!” he would declare matter-of-factly in the early afternoon, sometimes the late morning, and off he’d go, calling the family dog to his side and shuffling through the gate, settling his hat comfortably and muttering dzień dobry‘s to those he passed along his way.

As the weeks progressed in late 2011, he admitted during weekly Skype conversations that the walks were becoming shorter and shorter. Walks all the way to the river became a rarity. Then walks to the fields became scarce. Then the walks were confined to the yard.

And then they disappeared.

It might be trite to add “like all of us” to that previous sentence. Trite but true. We all disappear from the flow of everyday life, but so often those disappearances are so distant, people we’ve never met, never heard of. Indeed, the vast majority of deaths in the world go completely unknown to all of us. Almost all of us. It’s the “almost” that gets us sooner or later. And so that’s why it’s difficult to comprehend the loss of Dziadek, to accept the loss of someone so central to our lives.

Yet there’s no choice: we must accept it. Some things are easy to accept: he’s no longer suffering, and that’s a blessing in itself. But we’re selfish; we think about “me” before we think about anything else. It’s our first instinct, and the rare people who don’t turn automatically, almost reflexively, to the first person pronoun we call saints. So perhaps being a little selfish about a loss is acceptable. Human.