The world must be regarded as containing something of a void in order that it may have need of God. That presupposes evil (56).

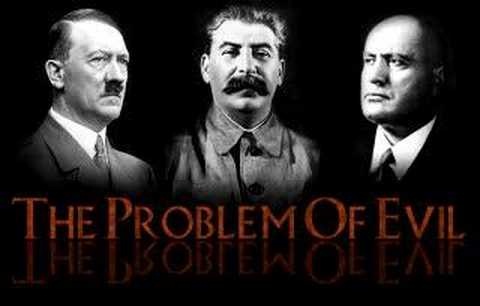

The problem of evil for many is the single most convincing argument for an atheistic stance. Dr. Peter Kreeft, of Boston College, writes, “The problem of evil is the most serious problem in the world. It is also the one serious objection to the existence of God.” He continues,

The problem of evil for many is the single most convincing argument for an atheistic stance. Dr. Peter Kreeft, of Boston College, writes, “The problem of evil is the most serious problem in the world. It is also the one serious objection to the existence of God.” He continues,

More people have abandoned their faith because of the problem of evil than for any other reason. It is certainly the greatest test of faith, the greatest temptation to unbelief. And it’s not just an intellectual objection. We feel it. We live it.

Standford’s Encyclopedia of Philosophy summarizes it thus:

- If God exists, then God is omnipotent, omniscient, and morally perfect.

- If God is omnipotent, then God has the power to eliminate all evil.

- If God is omniscient, then God knows when evil exists.

- If God is morally perfect, then God has the desire to eliminate all evil.

- Evil exists.

- If evil exists and God exists, then either God doesn’t have the power to eliminate all evil, or doesn’t know when evil exists, or doesn’t have the desire to eliminate all evil.

- Therefore, God doesn’t exist.

The problem of evil has a mirror image, though I didn’t see it for many years. For many years, I encountered only the standard responses about the limits of human knowledge and “the best of all possible worlds” argument. Then there are the theodicies, which all reduce down to the proposition that freedom of will necessitates the option to do evil. But the flip side of the problem of evil is the problem of good: if things are the result of atheistic chance, why is there beauty, and relatively speaking, so much of it? Indeed, humans seem obsessed with the creation of beauty, though we don’t always agree with the definition of “beauty” — especially in the case of modern art.

Thus, in a sense, Weil’s words constitute a kind of theodicy in miniature. Evil has often been described as a void, as a privation of good — and thus, having no real existence. It’s the absence of good. That does little to explain why a loving God wouldn’t do something about the evil that seems to suffuse the world, but it does reframe the issue in a way that puts evil in the proper relation to good: a void.