[W]hat does all this doctrine of kind interpretations amount to? To nothing less, in the case of most of us, than living a new life in a new world.

In a sense, that is what Lent is all about: taking steps to create a new life from our old life. We give something up; we take up something new. Old habits die — at least for a while — and new ones take their place. And in the midst of our ordinary lives, we find an extraordinary renewal.

At least in theory.

living a new life in a new world

Habits, once they settle in and unpack, tend to stick around, but that has the obvious bad side as well: in trying to break a habit, we’re trying to break out of a prison we’ve built and fortified and re-fortified all by ourselves, without much conscious thought. So I wish I could say I’ve been trying to employ new, kind interpretations to acts I previously would have chalked up to idiocy or malice. In the end, I’ve found myself consciously thinking, “Well, I should try to have a kind interpretation of this driver’s actions, but such idiocy as he’s exhibiting doesn’t really call for kindness!” As if. It’s like the cigarette smoker shaking out another stick, knowing full well she will regret it as soon as she touches fire to the tip.

The quoted excerpt is from Father Frederick Faber’s Spiritual Conferences, excerpted here.

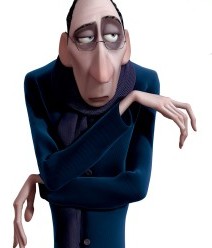

Criticism is easy, fun even. We can easily discern others’ faults, and it takes little imagination to capitalize on these faults, aggrandizing ourselves while belittling others. As the fictional critic Anton Ego says in Ratatouille,

Criticism is easy, fun even. We can easily discern others’ faults, and it takes little imagination to capitalize on these faults, aggrandizing ourselves while belittling others. As the fictional critic Anton Ego says in Ratatouille,