Tops

Few things are as beautiful to me as an English teacher as the tops of my students’ heads. Like thirty suns rising over the horizon of their desks, the sight of students’ crowns is a sure promise, an hint that today might be better than yesterday.

With pencils skating and tapping across their page, my students reveal the treasure in their heads through flawed but ever-charming drafts. They create maps of ideas that are perfect in their heads but somehow get a little muddled as they travel down their arms to their fingertips. But oh, the treasure they often share. What a strange and electrifying privilege to learn things about people that seem to be revealed only to the most trusted. What an honor to be the confidant of so many bright minds.

Yet it’s not just the content that brings joy. The process itself is almost sacramental. Some write with furrowed brow; others look like they’re smiling; still others seem both amused and confused; a few even seem ambivalent. There are exasperated sighs and frustrated moans, and the crisp echo of someone wading paper occasionally punctuates the grey-black scratching of graphite.

I’m always torn during such in-class writing engagements. I try to set the example and write alongside my students, sharing my own drafts and troubles so they can see that all writers have problems with writing. Still, part of me wants to sit and just watch as they wrestle with themselves. “I have trouble writing when I don’t like the topic,” they almost universally write in their first assigned topic, “I, the Writer,” an exploration of writing in their lives. To remedy this, I try to allow as much freedom as I can, and the fact that I can get thirty-plus thirteen-year-olds to sit quietly and write is a testament to the effectiveness of freedom. And so I work toward a successful medium: write a little, glance up and feel proud for them, then write a little more. My writing during these sessions often turns to the joy of watching students work.

It is most clearly in these moments that I see my vocation: I am a teacher. I will always be a teacher. I cannot imagine doing anything else, for I am addicted to the warmth and trust of my students.

Porch

Another Return To Table Rock, Redux

There’s a great trail along the stream and up the side of a mountain that’s just right for short legs.

There’s a fun swimming hole. There are tadpoles squirting about, drawing undue attention to themselves from would-be harassers.

There’s a cooling waterfall with which L becomes more and more courageous. (The corollaries to this is a new ability to put her face in the water and a develop preference of showering over bathing.)

There are smaller waterfalls nearby that are positively picturesque.

There are nature shows that allow kids to handle frogs, turtles, and multiple snakes, as well as learn about how helpful some snakes can truly be.

And there’s an ice cream shop just down the road.

Perhaps these are some of the reasons we keep returning to Table Rock State Park whenever we can.

Seven

First Day

It’s all smiles the first moments of the first day. There is optimism and perhaps hint of hope. New teachers. New year. A fresh start.

“I’ve heard she’s a little odd,” one says to another.

“But she’s really tough. That’s what Eric said,” another chimes in.

Next door, it’s the same story. The worries are identical. Will this be a cool teacher? Will I get along with her better than I did my last first period teacher?

“I’ve heard he’s really hard.”

“I’ve heard he’s really easy.”

Down the hall, the thoughts are the same. What will we read? What experiments will we do? Where will we go for field trips?

“I’ve heard he’s a jerk.”

“I’ve heard she’s really sweet.”

Everyone bumps around, unsure of themselves, unsure of their standing in the class, unsure of more things than they will care to admit. No one knows what to expect; no one knows whether to hope for the best or prepare for the worst.

“I’ve heard the cafeteria food is going to be better this year.”

“I’ve heard the dress code will change.”

Everything is in flux, sliding and slipping about like a ballerina on a well-greased floor. The only thing anyone has to go on is rumors and the Pop-Tart gobbled on the way to the bus stop.

And it’s all visible in the eyes, in the body language. The teacher clears her voice, signaling the beginning of the class, and everyone looks the same: shields up; defenses activated; look like a stone.

Who’s to blame them, for who is this person, this unknown, who will be an integral part of their lives for the next nine months? It’s a great poker game: no one knows if the teacher is the jackpot or three lemons. Everyone knows from experience that a great teacher can turn into a horrible ogre in a matter of days, and so everyone is afraid that it’s a front. The smile might not last; the attempts at jokes might not continue; the proposed classroom atmosphere of ease might be only an illusion.

It’s all rather like a blind date. The doorbell rings and there stands a bloke with a bouquet and a smile. The girl has her guard up and is analyzing every single thing the guy does: the jokes he cracks; the car he drives; the conversation he makes; the clothes he wears. Everything is a coded, hidden message, and the girl wants to know as soon as possible whether or not to text her friend who agreed to call her and speak in a loud, frantic voice about the impending emergency that she must, simply must, come and help with.

“I’m so sorry. I have to go. My friend’s cat is stuck in the dryer.”

If only it were that simple, for this date will last nine months. It’s a first date, a blind date, that’s the length of a pregnancy. And as with a pregnancy, there is nothing a friend can wildly scream over a cell phone, no emergency so great that it can end the date. And yet, the girl ponders, perhaps it won’t be so bad. After all, her cousin ended up marrying a guy she met on a blind date.

So the girl eases into the car and the students ease into the desks with a bit of worry and a touch of hope. This could all turn out well. The young man might be a perfect gentleman; the teacher might be a perfect instructor and mentor. Everyone decides for a moment, for a few days, to give the guy, to give the teacher, the benefit of the doubt.

Even those who are sure the whole school is involved in a vast conspiracy to trouble and torment them through their whole education entertain the thought that this year might be different. It’s sure to turn into disaster sooner or later, they think, but maybe it won’t be that bad. Maybe it won’t even be a disaster; maybe it will just be an inconvenience.

Everyone thinks, “Let’s wait and see.”

The teacher stands in front of the classroom, sees the sea of new faces, ponders the coming nine months, and thinks exactly the same thing.

“By the end of the first quarter, this girl might end up driving me nuts,” she thinks, looking at a face in the front row. “By the end of next week,” she shutters, “That guy in the back row might make me question my dedication to teaching.” The teacher looks, and explains, and waits. Waits for the first sign.

“We will have a test on every chapter,” she begins, and she sees the troublemaker in the back row yawn and prop his head on a casually balanced fist. “Oh, it’s already started,” she thinks. “I can’t make this any more interesting than this, and he doesn’t even have the decency to…”

In truth, it’s always like this. We are individual universes, carried around by clumsy bodies that often belie our doubts and fears. We assume, judge, and act on our initial prejudices, and then wonder why everyone else does the same. But sometimes, those judgments and quick characterizations set the scene for something more significant than a blind date. We are constantly moving into and out of each others’ universes, but we very rarely have any idea when we’ve bumped into someone who will have a major impact on our lives. But such moments do exist.

The first day of class is one. Students and teachers wake up on the first day of the new school year with the same thought: “I hope this year will be better than last year.” It doesn’t matter whether the previous year was a total disaster or an unqualified success. We always want it to be better. And we all hope, students and teachers alike, that it will be better.

Then the old routines return, and the students and teachers alike find themselves wondering, “What’s going on? How did it all go wrong?”

The dilemma is much more complicated than that, because we all have different ideas of what “wrong” means. Because we’re these universes — monads, as Spinoza called them — jostling around, unable ever to understand fully the physics of each other, we’re doomed to make mistakes that we don’t even know are mistakes. We offend where no offense was meant; we anger when we’re trying to amuse; we harm when we’re trying to help.

And nowhere is this more evident, more clear, than in the classroom.

What are we to do? We don’t have instruction manuals that we can read about each other. We don’t know what each others fears and dreams are. Sometimes we don’t know what words hurt, what actions destroy. Unless we tell each other.

That’s unrealistic. No one spills her guts walking to the car on a blind date. “Listen, I had a really bad relationship with a guy who always brought me roses. I associate roses with pain, so you might not want to bring them. They only call back bad memories.” No one says, “Listen, I am very insecure with my reading, and if you ask me to read something aloud, I will do anything and everything to avoid it–even if I have to cause a scene to get thrown out of class.” No one says, “I really want to help you guys, and sometimes I get really frustrated when people don’t seem to be paying attention. Then I make sarcastic remarks because I think it should be obvious.” No one says these things, but maybe they should.

So I will say these things to you. I am here to help you. I am on your side. I wake up in the morning with the hope of somehow making your life a little better. But I am human. I get frustrated; I get tired; I get irritable. I sometimes assume you should realize things that you might not necessarily realize. I occasionally assume that you didn’t this or that because you’re lazy. I catch myself, but sometimes the damage is done. Yet that doesn’t change the fact that I’m still on your side. I still am here for you.

Nap

Twenty

We jostle about in our adolescence, bumping against others and ourselves, usually questioning where we stand with others, often unsure of where we stand with ourselves. Such tumultuous times of identity formation, questioning, and reformation. We make and remake ourselves year after year, month after month, even day after day, and we’re all nagged by the same question: is the me I see in myself what others see? Or more to the point, is the me I see in myself the real me?

Sociologists and psychologists tell us that adolescence is a relatively recent cultural phenomenon, a product of the same innovations that created the leisure class and free time. In the past, one’s position in life was fairly well determined generations before one was born. Once born to generations of farmers, always a farmer; once born to a family of wealth and position, always an aristocrat. These days we wake up and find ourselves in possession of a driver’s license and a handful of friends, unsure what to do with either, and we struggle to make decisions that weren’t even available ten decades ago.

Every year, as an eighth grade teacher, I see my own students going through this, yet with seemingly infinitely more choices that I had. Their thumbs can move at over a phone’s small keypad at the speed of gossip, and last week is ancient history. They come to class sometimes with tears in their eyes, and I think, “Someone broke someone’s heart, and they’re both sure they’ll never survive it,” and I smile to know they will, because I did, and a hundred and twenty kids in my cohort did as well. “Love is blindness” I mutter under my breath.

I want to say, “Twenty years from now, you won’t worry so much about this. Like precipitates in a Chem II experiment, love and your personalities will seem somehow to have settled and congealed.” I want to tell them, “You’ll quote the Beatles: ‘I am he as you are he as you are me and we are all together,'” until I realize that U2 is their Beatles. (A student mentioned to me that he likes U2: “My friends think I’m crazy for listening to that old music,” he confided. Thanks.) I want to confide, “You’ll think to yourself, ‘Love is blindness,’ go to your twenty-year reunion, and find that you had more in common with everyone in your class than you ever realized.” But I know the words will do no more for their shattered hearts (egos?) than such words would have done for mine, and I’ll hope that some day, perhaps they’ll invite me to a reunion.

Heading Home

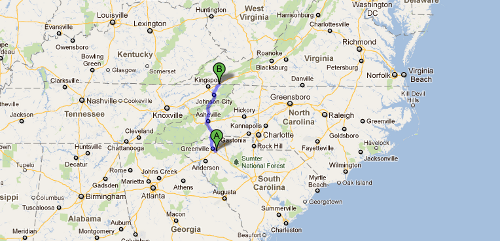

I grew up in a border town — half in Virginia, half in Tennessee — about three hours north of where we presently live.

In the last fifteen years, I’ve only gone back a handful of times. Today, K and I are making the trip to meet with people I haven’t seen in twenty years, most of whom I knew only in passing, and many of whom I probably won’t recognize, and if I do, I likely won’t remember their names immediately. Yet there are a few, and to see them again will be worth it.

I wonder, in the age of social networking, will future generations have twenty-year reunions?

Drips

Objective and Subjective Sexuality

Sometimes I wonder whether popular bands shouldn’t hire grammar consultants for their lyrics. I was listening to the Black Crows the other day, and as “Hard to Handle,” the Isbell/Jones/Redding standard, played, I noticed a grammatical flaw made the protagonist accidentally bisexual:

Actions speak louder than words

And I’m a man of great experience

I know you’ve got another man

But I can love you better than him.

I’m sure the lyricist meant, “I can love you better than he,” which is an elliptical version of, “I can love you better than he can love you.” Choosing the objective “him” instead of the subjective “he” simply means he’s loving the guy. Adds a whole new meaning to the earlier line about being “a man of great experience.”

The Beatles also fell into this exact same trap: using the objective case pronoun when it should have been the subjective case. This time, though, the song inadvertently turns the two girls between which the narrator is dithering into bisexuals:

If I give my heart to you

I must be sure

From the very start

That you would love me more than her

I’m sure Freud would have loved these.

Waterfalls

Throughout Transylvania County, North Carolina, there are virtually countless waterfalls. One can purchase a guide that provides directions to various sites, with some of the less popular ones including instructions like, “Turn right on the gravel road just past the fish hatchery. Drive 1.1 miles.” Yet many of them are easy to find; indeed, they’re hard to miss, like Looking Glass Falls.

Down a winding, paved path to an enormous rock outcropping, our family and our guests find our way to one of the most significant falls in the area. A fine mist drifts through the gorge combines with the cool water for a most effective chilling experience. All that’s missing is a chair and a good book (preferably a ratty copy: it’s likely to get ruined in the mist).

Lacking those things, we do what comes natrually: the children splash each other and K, and I switch the camera to the six-frames-per-second mode to capture fifty photos of the fun that will be whittled down to one or two.

We’re not the only ones playing, but it seems to me we’re taking the saner route to amusement. Of course, the adolescent head is impervious to rocks, adolescent arms never lose their grip, and adolescent feet are always sure and balanced.

After a bit of splashing around, it’s time to head further up the stream to Sliding Rock, the most famous and most popular attraction in the area. Indeed, it’s so popular that we arrive to find the parking has closed because of overflow, which means the wait times for the main attraction — obviously a large rock one sides down — are close to fifteen minutes.

Instead we head further up the stream to the education center, which houses the fish hatchery. In the outdoor “race tracks” (do they actually have contests?), we find the trout are, according to our New Jersey Polish visitors, upchani jak śledzie: apparently commuters and fish of all species can be described this way. The saying refers to the habit of packing pickled herring tightly in jars for storage.

After a picnic break, we contemplate returning to Sliding Rock. Instead, we go for one of the “turn right on the gravel road just past…” waterfalls.

It turns out to be not as much of a waterfall as it is an outdoor, stone-faced sprinkler. The floaties and life jacket we brought for the children are for naught.

Still, a lovely view, some nice light, and a chance to trek through the forest for a while. It is a teaching experience, one could say. But not a lot of fun. That would be Sliding Rock, and we decide finally to head back and see if it’s still packed.

It’s not, and in fact, there is virtually no line for the star attraction.

K goes first. After a while, she talks the Girl in to a short run with her.

Perhaps Sliding Rock will become yet another metric of growth: the first time the Girl slides solo. Eventually.

The Things We Leave Behind

Immigrants bring all sorts of things with them when they move to a new country. They bring items of their culture: language, songs, recipes.

They bring a love of native-language literature (even if it’s actually translated from another tongue) that excites them beyond words when they find someone else who seems to love a given book as much as they do.

But one thing they must leave behind is the confectionery that brings a smile to their faces and warmth to their hearts.

Off the Trail

Return to Table Rock

The plan was simple: get up at a reasonable hour, drive two hours to a spot in northern Georgia, and be awed at the fantastic views of a canyon known as the “Grand Canyon of the South.” But such plans begin taking shape the evening before, and when the evening drifts into the morning and all the adults are still awake, the likelihood of the plans coming to fruition diminishes greatly.

The backup plan — the realistic plan — was a return to Table Rock State Park. At only forty-five minutes away, it seemed a more logical choice for a late start. Being in the mountains, it also seemed a more comfortable choice.

We hiked the trail we always tale: Carrick Creek trail, appropriate both for its length (four-year-olds can walk only so far) and for its scenery, which is both beautiful and, more importantly for the kids, amusing. (Who doesn’t love playing in waterfalls or slipping and sliding on moss-covered rocks?)

The hike was more engaging with a game, so the kids had a contest: who could find the most trail markings on trees? It’s a common game we play with L to keep her interested in the walk. We played it in Slovakia a year ago, and every time we’re on a trail by ourselves, we encourage the Girl to look for the signs.

Despite the fact that both contestants marched right by trail makers without noticing them as they tried desperately to be first (apparently it was a dual contest), the game ended in a tie, which was frustrating for both the kids but a relief to the adults: one less wound to soothe. No one likes to eat a picnic when one of the diners is tinged with tragedy, feeling the sting of an unfair loss.

Any heated tempers would have been quickly cooled, though: the lake’s swimming area was closed, leaving only one option for cooling off after an arduous mile hike.