In Their Lives

In a world of spin and deception, to be trusted with someone’s greatest victories and deepest tragedies is rare indeed. For one hundred and some adolescents to trust someone that way can only happen in one, obvious environment: the classroom. The level of trust some students show (and hopefully, I earn) reminds me daily the privilege I have of teaching thirteen- and fourteen-year-olds.

Students write in essays and journals about things I sometimes worry few other adults in their lives know about: anxieties about the future; frustrations with current situations; sorrows over tragedies large and small. They come to me excitedly when they’ve done well, looking for a high five and a smile; they come to me dejectedly when something’s gone wrong, hoping for a sympathetic ear. They tell me when they’ve fallen in love and when someone’s broken their heart.

With some, I need to show only a little attention, ask a few questions genuinely from curiosity, and a smile blooms that makes my day and causes me to wonder why people would want to do anything else with their lives.

Motion

Those things which we take most for granted are usually the same things that we could not do without. It’s the paradox of familiarity: we sometimes say nastiness to those we love the most because familiarity breeds, if not contempt, at least laziness: we assume there will always be time for amends. We go from day to day assuming that the last words we say to our wife, daughter, parents that day won’t be the last words. We take for granted that we’ll wake up in the morning and be able to start, if not afresh, certainly again.

The alarm clock chirps and without thinking of the miracle unfolding in front of us, we casually slide our arm from under the sheet and smack another seven minutes of silence out of the clock. When we finally pull ourselves out of bed, an entire ballet of muscular motion has made it possible to sit up on the edge of the bed and rub our eyes in an attempt to smear the last bits of drowsiness away. A yawn is an engineering marvel that goes unappreciated, and lacing our shoes is as complicated as any dance.

Certainly that which we waste the most of is that which we can never replenish: time. We waste it as if our present moment were eternity, as if we were some kind of god, able to alter time and space and make an endless loop of tomorrows. Of all the meaningful things I could do with my time on a Friday night, for example, why do I sit and troll YouTube videos or play chess? “One day I will take all the photos and memories I have of Poland and write a book,” I promise myself continually, yet there’s always a caveat: “But not tonight. Tonight, I just want to relax,” and I load chess.com and drive myself to frustration over a silly game.

These three are related: the ability to move freely and the time to do so allows us to place our bodies in nearest proximity to those who mean the most to us. With few exceptions, these freedoms are universal, even in the most repressive regimes. It’s rare that something takes them away, at once, in a flash. It is necessarily an act of aggression, an imprisonment, a forcible, irresistible subjection of one’s will to the will of another.

Sometimes we imprison ourselves through misplaced priorities. We watch YouTube videos when there are more productive goals; we go to a class instead of attending our daughter’s performance; we rush conversations with our parents because some trifle is more important at the moment.

Occasionally, though, we’re blessed: something shakes us out of our assumption that that which we have now will never change and is therefore not worth cherishing fully at this moment. It might be something we experience that shakes us, that turns our head around, that lifts us for a moment to see where we stand and forces us to appreciate the view, regardless of what it might be.

Usually, though, it’s a vicarious glimpse of someone else’s experience, and often it’s an experience that we find ourselves wondering whether we could endure it, much less profit from it in any way. Watching The Diving Bell and the Butterfly (or reading it, I would assume–something that’s now a high priority) is just such an experience. French journalist Jean-Dominique Bauby, almost completely paralyzed by a massive stroke, wrote the entire book by blinking his left eye, the only part of his body that he could move. Claude Mendibil recited the letters of the French alphabet in order of their frequency, and Bauby blinked his left eye when he heard the next letter of the word he wanted to dictate. “E S A I T N R U L O” began Mendibil again and again until Bauby dictated, letter by letter, the entire text of the memoir he composed and edited in his head. That alone says more than most could in a lifetime of babbling.

It is, in short, a film all should see.

Prize

Best Friends

Happy Birthday!

Birthdays are, obviously enough, the temporal equivalent of borders or landmarks. We pass them and in theory are not the same on the other side. At least that’s what our culture tells us. Birthdays always bring to mind the now-odd notion that most people in the history of the world have had no idea just how old they are, so it’s a boundary because we say as much.

But they can provide real metrics of comparison. For instance, there are firsts in a child’s life that correlate to her age. Birthdays, then, can provide a dual marker: someone turns a year older; someone else experiences a first in relation to that.

Shortly after our arrival, K had her first birthday in the States. We were staying with my parents until we found jobs and settled into a city — eventually Asheville, though only for tw years. We went out to eat, had a cake — the usual.

Now, six years later, we celebrated once again with my parents: a grilled London Broil (one of K’s favorites) and all the summer accessories. Though the weather didn’t cooperate, it was nothing to the head grill chef: there’s no stopping a man on a grilling mission. It just can’t be done.

There’s also no stopping a four-year-old on a mission: as Papa was grilling in the rain, the Girl worked on perfecting her living room gymnastics and tumbling routine, taking occasional breaks to dance to the music coming from this or that program on Nick Jr.

But this birthday was different. Sure, there were Klondike Double Chocolate bars for desert — a first for all of us, but a relatively insignificant first.

Sure, K turned 26. I suggested she might want to do 25 for another year (she’s been in a holding pattern there, just as I, for a number of years now), but she decided to step out into a new age. Significant, but not earth-shattering.

What was most significant was, as always, how our daughter grew. It was the first year that L chose a present for K on her own.

It was a risky proposition.

She was insistent, though, on buying a new jewelry box for K. “The one she has is old,” she advised me sagely. “Mama needs a new one.”

So off went to find a jewelry box. What we bought was a candle holder, though. Pink, and shaped like a star, no less.

“I want this one!” L proclaimed when she saw it.

“You mean you want to buy this for Mama?” I clarified.

“Right.”

I tried to explain it wasn’t, in fact, a jewelry box. Yet the fact that it had a small door with a hing countered any argument I put forth. There’s reasoning with a little girl on a mission to buy a jewelry box for her mother.

Breakfast

Sześć Bab

I’ve always been fascinated by children of mixed culture, children who speak language X at home (Spanish, Hindi, German, you name it) and English everywhere else. Attempting to raise just such a child has shown me how difficult it can be.

The Girl understands Polish perfectly; she doesn’t speak it unless highly motivated. Part of that is due to living in a mixed household: I don’t always speak Polish around the house. (“Always?!” K would ask incredulously. “How about rarely?”) Additionally, the Girl spends her days in daycare with other English speakers. Polish is that language of babcia, dziadek, and her cousins.

“What you need to do is send her to Poland for the summer,” an acquaintance at the swimming pool advised. “She’s not too young!” the lady assured us over K’s protests that it was a bit much to force on a four-and-a-half-year-old.

Days like today, though, help: Polish friends from Asheville came for a day visit. That made three little girls in the same situation: perfect understanding of spoken Polish who exhibit great reticence to speak it themselves.

The hope was that, the two friends, just back from Poland and spending every day with babcia for the last couple of weeks, would speak Polish with the Girl. But if siblings of immigrants speak English to each other (which they usually do), it was perhaps only wishful thinking to hope that the three would break into unrestrained Polish.

In the living room, however, it was a different matter altogether.

In and out ran the girls; English to Polish to English ran their conversation.

Perhaps there was improvement; perhaps not. Perhaps that’s not the most important concern.

Bag Worms

They just about destroyed one of our Leyland Cypresses last year: Thyridopteryx ephemeraeformis, Evergreen Bagworms. They devour the needles of the tree, using some of them to camouflage their cocoon and the rest for nourishment. The females — who have no wings, legs, or eyes — remain in their bags their entire lives, and as they never lay their eggs, the new larva emerge from the mother’s carcass.

It’s a lovely little insect, in other words, one that we all love and long for. We just happen to have more than our share of them, and since no neighbors appreciate the sheer destructive capability of such a pet, we simply have to pick them off, one by one, and euthanize them.

It’s really an itch-inducing process that I don’t enjoy, but occasionally it yields a nice surprise or two.

What’s ironic is that we have at least three bird nests in those three, neighboring trees, and one would assume that having birds around would reduce the population of something like caterpillar larvae. Apparently, the camouflage is quite effective.

However, we have yet another tool at our disposal. We are breaking all conventions of warfare and going biological: Bacillus thuringiensis.

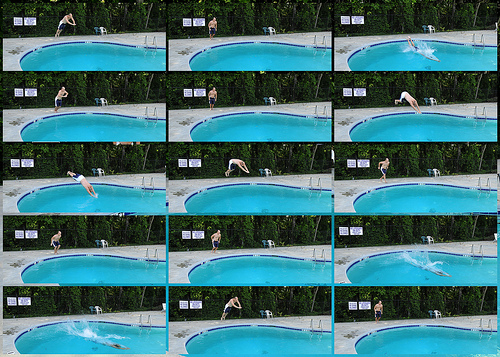

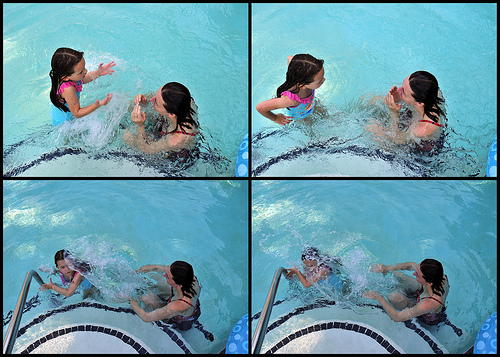

Another Day at the Pool

Another day at the pool, which meant two things.

First, more fun with the new camera: at close to seven frames per second, you can really get some good time-lapse sequences.

And second, the Girl learned an important lesson: if you’re going to splash someone because you’re mildly frustrated with her,

make sure that person can’t splash back more effectively.

A Day in the Pool

The Girl is out of daycare — I am the daycare, which means a number of things.

Her sleeping habits have changed significantly, for starters. When we are all heading out of the door by or before half past seven in the morning, we have to get her up so early that it affects her weekend sleeping patterns: she rarely goes past seven thirty. This summer we’ve discovered that she’ll sleep almost to nine if we let her. Which means a bit of time alone in the morning before she’s up.

Yet there are some negative consequences, most significantly, a lack of interaction with other children and less outside time. We don’t have a playground in our backyard, where as the Girl’s school has several: mornings on the playground were the daily ritual.

So we do the best we can. We take her swimming. Or, rather, jumping.

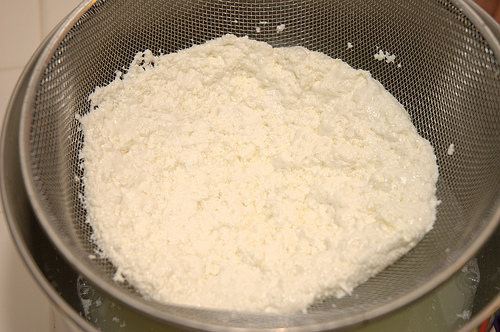

Cheese

At first glance, it looks like a bit of cauliflower. It is, in fact, a mixture of bacteria and yeasts — a fungus, of sorts. Kefir grains, used to make what Poles call “kefir,” what Russians refer to as “кефир” (pronounced the same) and what we call, essentially, buttermilk.

Production is simple: take the kefir grains, wrap them in gauze, drop them in a ceramic container, cover them with fresh milk, and let the mixture sit overnight. In twenty-four hours, you’ll have a chunky, lightly acidic buttermilk, that, an added medicinal bonus, has a slight alcohol content.

From there, it’s just a moment’s heating away from farmer’s cheese: mix the buttermilk with some fresh milk, heat, and strain.

In Poland, they do the same essential process with sheep milk, eventually forming it into oblong cheese blocks and curing them in a smoke house.

Roots

Ice Age

Waterfall

Table Rock State Park, Part II

Returning to places as a parent provides a yardstick for your child’s growth. The last time we visited Table Rock State Park, the Girl just shy of two years old. Her recently bald head was beginning to have enough hair to make her feminine, and she was beginning to talk. (When we watch videos of her at this age, though, neither K nor I can understand much of what she says sometimes.)

That first trip, she toddled along for some of the short hike, but most of the time, either K or I carried her in a frame-less child carrier: twenty pounds of wiggle followed twenty pounds of sweat-inducing insulation.

Three years later, and she is Miss Independence, resisting help on all but the steepest portions of the two-mile loop and occasionally pontificating, “It is time for a break!”

Last trip, she was barely aware of the camera; this trip, she posed. In fact, we had to tell her to stop posing occasionally: she has a tendency to get carried away.

Yet some things have not changed in three years: Baby still is a constant companion, having been hiking in the mountains of Poland, photographed on the town square of Krakow, and one harrowing time, left at Target for one terrifying night.

Imitation is still the order of the day, and fussing-filled frustration will likely be a frequent visitor for years to come.

Yet the changes. We stopped for a break, and the Girl was curious: “Where are we?” K pulled out the map and showed her. At the next bend in the trail, she asked for the map to try to find where we were. The fact that she was completely off is of no importance: the curiosity is the treasure.

Curiosity was enough later to overcome fear and touch a corn snake in the nature center. K took a step further in overcoming that latent terror that seems to be in all of us almost instinctively.

Most telling was the conclusion: splashing about the lake with restricted parental supervision (the swimming area was about to close, so there was no time for us to change anyone but the Girl), she gravitated toward the deeper portions.

She called out, “Look how far away I am from you, Mama!”

Games

It’s a lifelong process, learning how to lose. I’m thirty-some years older than the Girl, but I still fight the frustration of loss just as much as she. I could contend that there is a difference: losing at games of chance doesn’t phase me because it’s a question of luck; losing at games of skill–read: chess–does bother me when I feel I made a stupid mistake. Such distinctions are lost on the Girl, though: losing is losing is losing. It all hurts.

We’ve been working with the learning how to lose (and to a lesser degree, how to win gracefully) with Candy Land for ages. We’ve seen some real improvement: the complete hysterical fits have disappeared, replaced by a temporarily pout and an extended lower lip. In fact, things are going so well that I’ve stopped my Machiavellian parenting technique of stacking the deck to make sure she loses at least once or, if needed, wins once.

Yet sometimes that dimension of untinkered-with chance provides some amusement: three candy cards within four turns for me resulted in some whiplash-inducing jumps around the board and laughs for the Girl — even when I was surging ahead. Perhaps she knew the next card would bring me back to Earth.

Sunset After the Storm

Fourth

The Girl is a strange eater. In truth, she’ll eat anything if she’s cooked it. For a long time, as a child, her favorite thing to cook while banging around the kitchen was “blue zupa,” a hybrid Polish and English name (“zupa” is Polish for “soup”) for an imaginary, favorite-colored dish. K and I ate countless pots of blue zupa.

We eventually bought L some realistic play pots and pans at Ikea, and she moved from more imaginary to less imaginary. It’s truly amazing what you can cook from blue and pink Play-Doh.

When it comes to more realistic food, though, the Girl has slightly different tastes. She likes some of the standards: spaghetti and pizza are always welcome on the table. Yet other childhood favorites have always been less popular. For instance, she just ate her first hot dog over the Fourth of July holiday. Granted, she hasn’t had much exposure to hot dogs: we eat them probably twice a year at most, if even that often. Still, she sees them at school, and probably sees how the other kids virtually inhale them. That peer pressure has had no effect (if only that would continue).

Yet non-typical foods she adores. Exhibit A: barszcz. Her favorite food, without exception, is a traditional Polish beetroot soup. She’s absolutely obsessed: she’ll eat it once a week without fail, more if we let her.

She’s also eager to bring her best friend from school to try it.

“What will you do if E doesn’t like it? If he tries it and says, ‘I don’t like it.’? I ask.

“I’ll tell him, ‘You just have to try it,'” she replies.

“But what if he tries it and doesn’t like it?” I press.

Try it and not like it? Unthinkable.

Reunion

One would think, to some degree, reunions will become a thing of the past in the age of social networking, especially class reunions. After all, part of the fun is to find out what everyone else has been up to; with everyone on Facebook, we already know all of that.

Yet we’re a gregarious species by nature, and looking at pictures on a monitor and chatting by Skype is still no substitute.

So we gather together from time to time to look at old photos

and take new ones. Decades separate the two photos, and children who barely make it to their mothers’ waistline now have children who have children who have children. Even when only a relative handful of them gets together, they fill the frame easily.

Several of them are, for all intents and purposes, strangers. Grandchildren of great uncles, cousins removed by years and geography. Yet just say the word “family” and strangers are no longer so distant, and introductions come easily.

If only we could learn that as species.