Puzzles and Dolls

“Do you dream of being a princess?” coos one of L’s Christmas gifts before offering game-play options.

Why does L have such an obsession with princesses? It’s not like we initiated it, though we’ve done very little to encourage or to discourage it. (Relatives are a different story!)

Granted, L has watched the films several times: Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty, The Little Mermaid, and several other princess films. She has a few princess books — usually thick books we refer to as “the princess collection” and “the other princess collection.”

“Do you dream of being a princess?”

My concern is not necessarily the notion of being a princess; it’s the notion of being a twenty-first century princess, a highly sexualized image that encourages girls to flirt in grade school and has teen fashion magazines offering advice on the cover for how to have a “sexy beach” hair do.

“It’s a long way off,” some might say. “She’s only four.” When I hear stories of six-year-olds getting cell phones, though, I realize the pressure begins shortly.

Or perhaps it’s already begun, the pressure to meet society’s standards of what a “Real Girl” is like. Perhaps that’s what the princess obsession is all about.

Perhaps. It’s somewhat depressing to think that we’re entering a period during which peer pressure is as influential as — if not more than — parental influence. There’s a balance there that we are just beginning to feel out. Its contours are still nebulous because the actual relationships and ratios are still unclear. In the end, it’s all about awareness.

If only it were that simple.

Snowball Fight

St. Stephen’s Day

Just before noon everyone begins heading home. Snow on the ground, wet roads, freezing conditions — perfect weather for sandals and a drive to the mountains. As some of our guests head off to the mountains of western North Carolina, L has other priorities: a snowman.

We’re lucky: the snow is wet and heavy, easily rolled into balls. Indeed, we could roll up all the snow like a gigantic carpet: it picks up snow, leaves, grass, and all.

When I was growing up in southwest Virginia, I rare saw snow, and even more rarely saw wet snow. It was most often dry, powdery snow good for skiing perhaps, but of little use to neighborhood kids wanting to create snow forts and have snow ball battles.

This snow is as easily rolled as insulation or blankets. In fact, it’s almost too easy.

As K directs everyone to the front yard, we realize that carrying the growing snow balls is almost impossible.

“Roll them,” K instructs simply.

Which means the snowman will be bigger than originally planned.

By this time, L has lost interest and is more concerned about whether or not she’ll get to make a snow angel.

“We might be able to just before going in,” I tell her. “But it makes you very wet, so we’ll have to go in right after you’re finished.”

A tricky situation: L is sick (as seems to be the new Christmas break tradition — three years in a row), but snow is so rare, it seems a shame to herd her back inside so quickly.

We finish up the snow man, snap a quick picture, then return to the warmth of tea and dry clothes.

The theme of warmth and tea continues through the evening: a last dinner with friends to bring the 2010 Christmas season to a close.

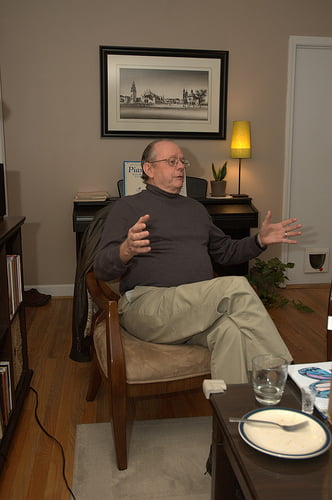

The familiar gender segregation returns, with the ladies in the living room, the gentlemen still at the dining table,

and the kids watching Toy Story — probably for the tenth time for L.

Things wind down: time for children to go to bed and K and others to prepare mentally for a return to work tomorrow.

A bittersweet moment in the end: it could be the last Christmas we spend with one family, as they’re contemplating a return to Poland. Maybe we’ll get together next year; maybe we’ll only be able to share Christmas wishes over the phone. But for now, we depart, looking forward to Friday’s Polish New Year’s Eve party.

Christmas 2010

“There’s a forecast of snow,” was the rumor running through the house. “It’ll be the first snow during Christmas since the early 1960’s.”

By the time the guests arrived in the late afternoon, there were flurries. The temperature stayed above freezing, but the snow and festive mood led to the only logical conclusion: toddies for everyone.

The evening continued, as did the snow and conversation.

The usual gender self-segregation gradually developed: the ladies in L’s room,

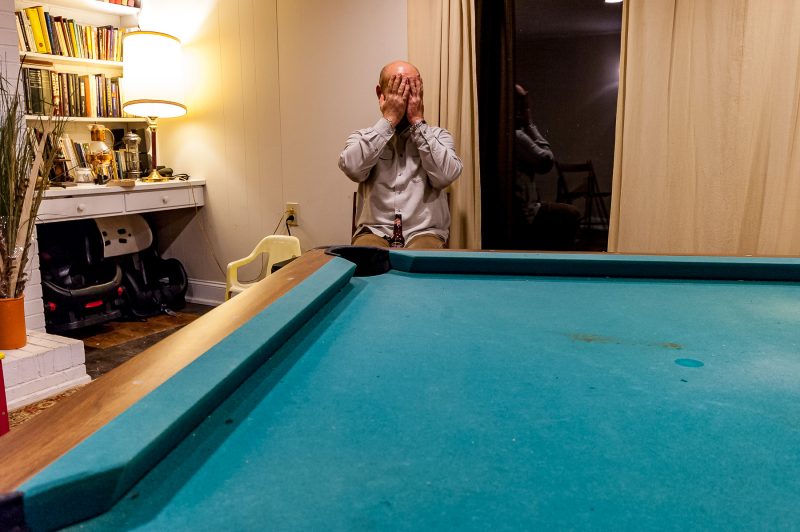

the guys in the basement, and the children moving back and forth between.

Visiting friends’ dogs and the pool table seemed to have an inordinate draw for the kids. I remember as a child the fascination I too held for the concept of billiards. It seems like the perfect kid’s game, which I guess it is: flat surface, lots of balls, purposeful collisions. Sort of like a demolition derby.

I excused myself for a few moments to take some photos of the house in snow. I tromped through the first Christmas snow in almost fifty years, thinking about the privilege inside and out, that having close friends is as rare and dear as Christmas snow in the south.

Wigilia 2010

The food is prepared. The guests have arrived. The table is set. It’s time for the most-anticipated evening of the year: Wigilia, the traditional Polish Christmas Eve dinner.

It’s the thirteenth time — seven in Poland, six in the States with K — that I’ve experienced what has become the highlight of the year.

We exchange the opłatek, sharing wishes for the coming year. Variations of “May this coming year be better than this closing year,” the eternal hope of humanity, echo through the kitchen.

We begin the parade of food: two soups, dumplings stuffed with cabbage and mushrooms, fish, salads, rice, desert after desert. Tradition dictates repetition, and the menu is no different. We have the same soups every year: barszcz z uszkami (borscht with dumplings) and wild mushroom soup. We have salmon as the main fish course, this year stuffed with crab meat.

The appeal of tradition, though, is that you know what’s coming. There are no surprises. We’re comforted in the knowledge that at least this one thing has not changed, for change isn’t always positive. So while we play with the idea of switching the menu — maybe having a different fish — we always end up following tradition.

After dinner, we open gifts. When I hear about some people’s expectations for Christmas presents (suggestions to buy $2,000 rings, piles of clothes, multiple video games), I wonder what’s the point. Such a Christmas is spoiled if one doesn’t get one’s material lusts satisfied.

I often wonder how many people have such materialistic, shallow Christmas experiences: getting gifts, then retreating into solitude to play with the toys. It’s as if they’ve forsaken the real treasure of Christmas for silly trinkets.

The real treasure is family and friends gathering together to share some laughs and companionship.

Previous Years

Before the Storm

The day before Christmas Eve in a Polish household is always frantic. Cakes to bake, salads to make, and general culinary chaos.

The heating system dying in the morning didn’t help, though. The verdict: the zoning system’s main control board is malfunctioning. Cost: the part alone runs $1300. Time to make some decisions. Merry Christmas from Arzel.

In the meantime, we have baking to do. Cheese cake, for instance, requires room-temperature ingredients, a fact inconveniently forgotten by inexperienced bakers the world over.

Fortunately, we had a little helper today to get us through the tough parts. Without her valuable advice and assistance, I’m sure we would have got finished much more quickly than we did been at a complete loss.

With her in the kitchen, it’s a constant battle against her curiosity. “I want to do it!” is her refrain.

At the same time, how can one battle curiosity? Who would even want to? It’s a question of direction and redirection.

Polyglot Concert

Our daughter, thanks to a bi-lingual mother and multi-lingual daycare, knows songs in four languages.

First Solo

Jasełka

Nativity plays date at least from the time of St. Francis of Assissi, eight hundred years ago. This weekend, the concept was, once again, Polish-ized.

To be fair, it was not a one-off occurrence. Nativity plays, called jasełka (ya-sewl-ka) in Polish, are as customary during the Christmas as wreaths and carols.

Unlike the modern American nativity play, which is often relatively high tech and performed by adults, Polish nativity plays are almost always entirely a production of children and adolescents — under the direction of adults.

So in schools and churches throughout the Polish community worldwide, children are have been putting on nativity plays much like the one the small Polish community here watched this afternoon.

Yet this play was somehow different — incredibly different — than all the plays I watched while teaching in Poland. During the final days before Christmas break, students and faculty gathered to watch the year’s play: it was often, it seemed to me, an attempt by the directing teacher simply to impress the other teachers.

These actors were American children of Polish heritage, children who speak English naturally and Polish only when spoken to by an adult. Their Polish has the traces of limited exposure: accents, weak grammar, lower-level vocabulary: they speak Polish like I do, in other words. For all intents and purposes, Polish is a virtually-foreign language to them.

For them, it’s the language of parents and parents’ friends, a language to be spoken only when spoken to. When they sit around, waiting for their scene during rehearsal, they lapse to the more comfortable English, the language they speak without thinking.

And yet they memorized line after line, exchange after exchange, and performed it with few cues.

It was a showcase, a moment for kids to show their musical, acting, and linguistic talent. It was a celebration of one of the pivotal events in history — the pivotal event in the West.

At the heart of the afternoon was the sense of community, the sense of belonging. In between scenes, the audience joined the kids in various renditions of the most popular Polish carols. Put ten Poles in a room together and they’ll end up singing: yet somehow, in suburban America, it had a special glow.

For K and me, there was a first — a first of many, I’m sure. As part of the finale, L sang a solo.

She was was off pitch and out of tune, but it was the sweetest moment I’ve ever experienced as a father.

Lighting the House

We’re moving up — literally. This year was the first year we put up lights around the house.

It was easier than I was expecting, just a matter of up and down and up and down the ladder.

And the realization that what comes up before Christmas must come down shortly thereafter.

Still, to sit in the living room is a double pleasure now.

Preparation Begins

When Christmas Eve dinner includes two soups, multiple courses, and more desserts than one can possibly imagine, it’s a good idea to get started a little earlier.

Ten days ought to do.

And so last night we began by preparing the cabbage/mushroom filling for the dumplings. It’s neither a long nor a labor-intensive process, but when there will be cakes to bake and soups to season during the days before Christmas, it puts things into a little different perspective.

So last night we cooked the sourkraut, sauted the onions, ground them to a literal pulp, mixed a sprinkle of bread crumbs and called it a night.

Tonight, stuffing and fast-freeze.

Stacking the Deck, Redux

L and I are playing Candy Land. It’s a dry, boring game, to be honest, but I’m not doing it for my own entertainment: that comes from watching her.

Still, I’ve been trying lately to make it a learning experience, as a way to help her deal with her frustration. It’s a simple premise: stack the deck occasionally, placing the Candy Cane Forest card for the next drawing when she’s seventy-five percent complete.

“Oh, rats!” she declares, retreating almost to the beginning of the game board.

I try to make it a little more frustrating, dropping the ice cream cone card into place for my next drawing. Will she get frustrated that she “obviously” has no chance to win? Will she want to stop? Will she complain?

No — nothing but a laugh.

There’s only one thing left to do: make sure she gets a few doubles to catch up — not win, but catch up.

The game takes longer than it would have if we’d just drawn and let chance decide the winner. But the girl has uncanny luck and wins more often than not. A loss or two does the spirit good.

A Basket of One’s Own

The Tree

We sit in the living room, K writing Christmas cards, L drawing on them. I alternate between reading student journals and whatever book my eye falls on — skimming books of my past and those I still haven’t made it to (Berger, Weil, Schleiermacher, Smart), all within reach of my chair.

The tree is done; the mess cleaned up. It sits glowing in the corner. Were there a fireplace in the living room, it would probably be snapping and crackling now.

Shawn Colvin’s Holiday Songs and Lullabies finishes, setting the mood.

There’s tea steeping in the kitchen (a rooibus that L chose), and it’s actually cold outside.

We switch to Polish carols and dream of snow.

Fourth

Time is a relative thing. Scientists tell us that we can travel so fast that time slows. In 1582, Pope Gregory XIII convinced the whole western world to skip ten days.

Yet it’s the smaller moments that have the true significance.

It’s the smaller moments that see a devoted mother spending an entire Friday afternoon baking a cake for a little girl and her guests.

It’s the sweeter moments that see the welcoming of a beloved friend with mutual squeals of joy and anticipation.

It’s the moment less than the flickering of a candle that we all remember, the moment that a little girl has been excited about for days.

It’s the moments that finds us surrounded by friends,

friends who have taken a few minutes out of their lives to come celebrate with us.

Within these series of moments, I catch a glimpse of the future. It happens every now and then: a pose, an expression, a gesture, and suddenly I see what our sweet daughter will look like in five, ten, fifteen years. A birthday celebration offers a hint of birthdays to come, and the bitter-sweet realization that these present moments are disappearing all too quickly.

The pony rides will disappear. “Oh, Tata — I’m not interested in ponies anymore.” It’s bearing down on us, this reality, and I both dread and eagerly look forward to it.

In the meantime, we — family and friends — enjoy the moments of helping and hugging, the moments of screams of laughter often followed too shortly by cries of frustration. There’s a big girl inside our L, but she’s still a little girl. Almost one year older now, but a little girl all the same.

“Technically, it’s not your birthday,” I try explain to her.

“You mean I don’t have my birthday party?” she replies, in a panic.

“No, you’re having your party today, but your birthday is Thursday.”

“But Mama said today is my birthday. Today is my party!” There’s a certain panic in her voice that tells me that time is such a relative, elastic thing — after all, in Asian cultures, children are born one year old — that I can shift time and calm a panicking daughter with few repercusions.

“Well, Mama was right,” I relent.

“You were just joking,” L giggles.

Perhaps, but not about this: happy early-birthday, our sweet daughter. May all your birthdays be raspberry-covered and laughter-filled.

Smells

Visitors

Moving provides the great disadvantage of distanced friendships. Folks we used to see on a regular basis become rare visitors, and vice versa. (The road to Asheville is, after all, two-way.) Still, the advantage of that is the pleasure of spending time with “old” friends.

Time passes so quickly that it’s difficult to know when someone goes from “friend” to “old friend.” How long do we have to know each other? How quickly can time disappear? Those questions seem somehow connected.

“How long has it been since we last spent time together?” we were trying to decide last night.

Long enough that are children are no longer the children of our memories. L now talks and runs and schemes: a far cry from the toddler our friends last saw. And their son: in my mind, he’s still L’s age, and then he walks in the door.

He’s a school boy now, with new interests and new abilities.

“He wants to learn the guitar,” his mother says. We get L’s little guitar out and he strums a bit, fingering a note or two, though not quite sure where. At some point, hopefully, L will develop an interest in learning some instrument: hopefully not tuba or drums.

The interest in billiards already exists, but I suspect (from personal longing) that it exists in all children.

There’s something almost intoxicating about sixteen fast-moving balls in an enclosed space.

Visiting with children has its risks, though. We let them stay up beyond their bedtimes, knowing that once they go to bed, we’ll stay up for another hour or three. The hope is the vain hope of all parents: that by putting off bedtime by an hour and a half, we’re somehow magically putting of the wakeup time by the same amount. It never works, and yet we’re hopeful each and every time.

And it’s a trying situation, no matter which side of the guest/host relationship you’re on: if you’re the host, you don’t want your daughter yelling at a little past seven waking up your guests when everyone has only been in bed a few hours. If you’re the guest, you don’t want your daughter yelling at a little past seven waking up your hosts when everyone has only been in bed a few hours.

But if you’re L, you wake up when you wake up, and a ritual is sacred: there must be chocolate soy milk, warmed in the microwave for thirty seconds, and stirred with a specific spoon. Etiquette has no place in a thirsty girl’s thinking.