He walked onto the court, fully suited up, and all eyes were on him. In helmet and full pads, Ron stood in stark contrast to the other players, who wore tank tops and baggy pants. Their shoes squeaked on the hardwood floor while Ron’s cleats clipped, clopped, and slid about. He was ready for the game, though, and eagerly awaited the start.

Jump ball and the opposing team had the ball. Though his start was awkward as his metal cleats slid across the highly polished floor, Ron quickly got up to full speed and tackled the opponent who was, oddly enough, tempting fate by bouncing the ball on the ground. Full contact–the player went down, the ball shot off toward the center of the court, and Ron was just about to dive on it when he heard the whistle.

“Foul!” cried the ref, and Ron was confused. It had been a clean hit. There was no unnecessary roughness. Still, he shook it off and prepared for the next play.

The opposing team opted for a pass from the far sideline. Ron timed his hit perfectly: just as his victim’s fingers came in contact with the ball, Ron rammed him, driving his foe to the floor.

Another whistle; another foul.

Two clean hits in a row and mysterious fouls called on both. Ron was perplexed the first time; the second time, he was getting heated.

When his third tackle brought another foul and an ejection from the game, Ron was livid. He began yelling and screaming at the ref, protesting violently all three fouls and suggesting that the official was visually impaired.

Yet the spectators and players were utterly confused at Ron’s reaction. It was if he didn’t have any idea that the rules he’d brought onto the court weren’t the same rules everyone had agreed upon for the game. They weren’t even close. And yet, instead of trying to figure out why everything seemed to be going against him, instead of asking for help, Ron ranted violently. The referee tried to explain that Ron was applying the wrong set of rules to the game, but all Ron heard was gibberish. The ref might as well have been speaking Greek, and this infuriated Ron even more.

Finally, he declared that he couldn’t wait until this game was over and plopped himself down in the middle of the court, ignoring all pleas to move so the game could continue.

In the process of reorganizing the basement storage/work room, K and I have been tearing open boxes that have sat virtually untouched for years. Most of it consists of my own belongings, packed up while I lived in Poland in the late 1990s (eventually repacked into sturdy Rubber Maid storage bins). My parents moved, and instead of making the decisions for me, they left it to me, ten years later, to go through the stuff and toss out that which was once treasure but now trash. Granted, I could have done it earlier, but I lacked the serious motivation. Who wants to root around through old boxes of memories?

In the process of reorganizing the basement storage/work room, K and I have been tearing open boxes that have sat virtually untouched for years. Most of it consists of my own belongings, packed up while I lived in Poland in the late 1990s (eventually repacked into sturdy Rubber Maid storage bins). My parents moved, and instead of making the decisions for me, they left it to me, ten years later, to go through the stuff and toss out that which was once treasure but now trash. Granted, I could have done it earlier, but I lacked the serious motivation. Who wants to root around through old boxes of memories?

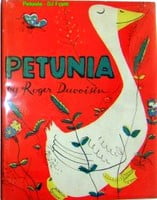

Her collection grows, and her eyes always light up when she gets a new book.

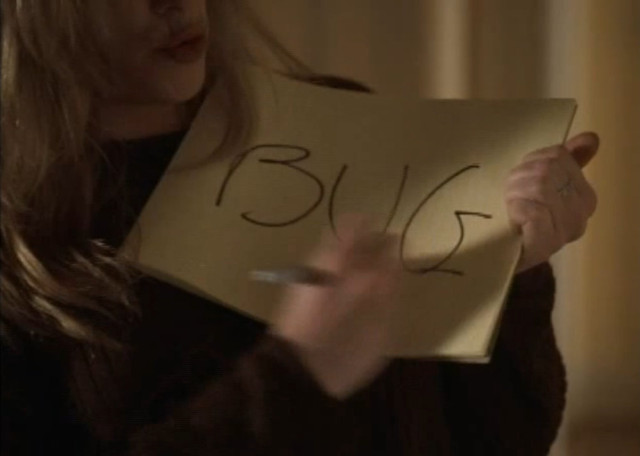

Her collection grows, and her eyes always light up when she gets a new book. The evidence was everywhere: an empty wrapper; brown stains around the mouth; dark smears down the front of the dress; cocoa breath; the knick-knack box that stored chocolates sent from Babcia in Poland on the floor open.

The evidence was everywhere: an empty wrapper; brown stains around the mouth; dark smears down the front of the dress; cocoa breath; the knick-knack box that stored chocolates sent from Babcia in Poland on the floor open.