The oddest thing for an inhabitant of Poland to be writing: we had an earthquake yesterday at around 6:20 in the evening.

It was a slight little hiccup by most standards: 3.6 on the Richter scale. Kinga was at home and said she felt the building shaking for about five seconds. I, on the other hand, was walking home and felt nothing. Reportedly in the nearest town, some houses were shaken enough that books fell from the shelves, and on the other side of the Tatra Mountains, Slovakians reported having felt it.

No reports of damage, but of course everyone’s talking about it.

Earthquake and Poland — they go together about as well as . . .

Undoubtedly my favorite contemporary composer, Górecki often vies for “best composer of all time” in my opinion – it all depends on when you ask. It was his music, particularly his Third Symphony (subtitled”Symphony of Sorrowful Songs” –

Undoubtedly my favorite contemporary composer, Górecki often vies for “best composer of all time” in my opinion – it all depends on when you ask. It was his music, particularly his Third Symphony (subtitled”Symphony of Sorrowful Songs” –  It’s enough, I suppose, that I got to experience his Third Symphony, under his own baton (well, no – he didn’t actually conduct with a baton), in a location that was intimately connected with the text of the second movement.

It’s enough, I suppose, that I got to experience his Third Symphony, under his own baton (well, no – he didn’t actually conduct with a baton), in a location that was intimately connected with the text of the second movement. After the concert, the orchestra performed “Sto Lat” (“100 Years”), the traditional Polish well-wishing song. Mid-way through, Górecki jumped onto the podium again and directed everyone, audience and orchestra alike.

After the concert, the orchestra performed “Sto Lat” (“100 Years”), the traditional Polish well-wishing song. Mid-way through, Górecki jumped onto the podium again and directed everyone, audience and orchestra alike. After some well-wishing and chatting, the orchestra came back out and they did a playback recording session, as this is intended to be a DVD released sometime later. It was a strange thing – they were basically making a music video, playing along with their earlier performance. They played for a bit – most of the first movement – then suddenly the director stopped everything just as the music reached it’s most emotional point. Strange how art can so easily succumb to commercial needs.

After some well-wishing and chatting, the orchestra came back out and they did a playback recording session, as this is intended to be a DVD released sometime later. It was a strange thing – they were basically making a music video, playing along with their earlier performance. They played for a bit – most of the first movement – then suddenly the director stopped everything just as the music reached it’s most emotional point. Strange how art can so easily succumb to commercial needs.

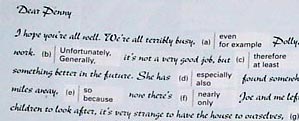

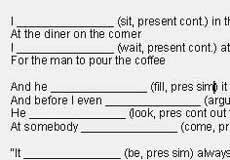

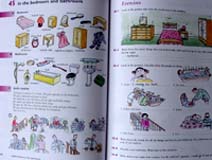

Ever wonder what an EFL (English as a Foreign Language) textbook looks like? I certainly did as I was preparing to come to Poland for the first time back in 1996. After all, how often do you get to see a textbook teaching something you already know fluently? Naturally, after four and a half years’ experience, I’ve seen and used more textbooks than I care to remember. I thought I’d share a little about the books I’ve been using.

Ever wonder what an EFL (English as a Foreign Language) textbook looks like? I certainly did as I was preparing to come to Poland for the first time back in 1996. After all, how often do you get to see a textbook teaching something you already know fluently? Naturally, after four and a half years’ experience, I’ve seen and used more textbooks than I care to remember. I thought I’d share a little about the books I’ve been using.

I am a high school English teacher in a small village in southern Poland. One of the things that still amazes and annoys me, after more than six years of teaching here in Poland, is the culturally engrained habit of cheating. Simply put, the majority of students here will cheat in any and all perceived opportunities.

I am a high school English teacher in a small village in southern Poland. One of the things that still amazes and annoys me, after more than six years of teaching here in Poland, is the culturally engrained habit of cheating. Simply put, the majority of students here will cheat in any and all perceived opportunities. Two examples show the tolerance Poles seem to have for cheating:

Two examples show the tolerance Poles seem to have for cheating: But how do they do it?

But how do they do it? I even fail them if the appear to be cheating! I’ve told them, “If your lips move, you get a ‘1,’ because am I to know what you’re saying?” It’s excessive, in a sense, and even unfair, but I know if I’m not this strict, they’ll say, “I wasn’t cheating! I was asking for a pencil/tissue/eraser/whatever.”

I even fail them if the appear to be cheating! I’ve told them, “If your lips move, you get a ‘1,’ because am I to know what you’re saying?” It’s excessive, in a sense, and even unfair, but I know if I’m not this strict, they’ll say, “I wasn’t cheating! I was asking for a pencil/tissue/eraser/whatever.”