Polish is, beyond a doubt, the most difficult language I’ve ever attempted to learn. In a way, that’s not saying much: I “studied” Spanish in high school and French in college; living in Boston, I began learning a little Russian until the novelty wore off; in Poland, I decided to learn some Greek. But Polish puts them all to shame.

Polish is difficult and strange — even Poles will admit that. The pronunciation is tongue-warping and the grammar is unbelievable.

I recall an instance when four teachers — three German teachers and an English teacher — were writing an official letter of thanks and spent a good three to five minutes discussing how a particular word should be declined (i.e., which ending should be used). One of them looked at me and said, “You see, Gary, you’re not the only one who has problems with this hopeless language.” In fact, I’ve often seen teachers who are preparing some formal paper or task asking the Polish teachers whether something should be this way or that in a given case.

What follows is a basic outline of why Polish is so difficult.

Declension

In English, word order is an essential grammatical element. We know in the sentence “The dog bit John” that the dog did the biting, and not John, from the position of “The dog” in the sentence.

Polish, however, is an inflected language and that means that word order has no effect on the meaning of the sentence. In Polish, you could just as easily order the words, “John bit the dog” without any change in meaning. For that matter, “Bit John the dog” and “The dog John bit” are possible as well.

So how are they differentiated? By their ending. In Polish (in all highly inflected languages) you indicate a word as a direct object, an indirect object, a subject, or whatever by adding a suffix according to a given pattern.

An example may help. Imagine in English that subjects ended in “-doj” and direct objects ended in “-aldi.” Our sentence would then look like this: “The dogdoj bit Johnaldi.” In that case, “Bit Johnaldi the dogdoj” would have the same meaning, as would the following:

- “Johnaldi bit the dogdoj.”

- “Johnaldi the dogdoj bit.”

- “The dogdoj Johnaldi bit.”

| The genitive case singular ending of “non-alive” nouns, either -u or -a, is decided by the morphology of the noun, not by its meaning. Polish: An Essential Grammar by Dana Bielec, page 109. |

English does indeed have a bit of declension. Some examples:

- “-ed” to a verb to make it past tense

- “-s” to make a noun plural

- “-ing” to make a verb a gerund (i.e., “Swimming is a healthy activity.”)

- “-er” and “-est” in the comparative and superlative forms

- “-‘s” to denote possession (i.e., “Samantha’s mother left for Switzerland.”)

By and large, though, English is not an inflected language. “The dog bit John” and “John bit the dog” are very different sentences as a result.

An inflected language uses cases to differentiate functions and forms. Greek has four cases. German, I believe, has five.

Polish has seven:

Case |

Use |

| Nominative case | The subject of a sentence |

| Accusative case | The direct object of a positive sentence |

| Genitive case | To denote possession (i.e., “That’s George’s bag.”) The direct object of a positive sentence for some verbs The direct object of a negative sentence For quantities of five and above (more later) |

| Locative case | To specify location after certain prepositions |

| Instrumental case | To denote the method or tool used to do something |

| Dative case | The indirect object of a sentence |

| Vocative case | Used in addressing people (i.e., Did you take it, George?) |

These changes even occur to names, providing a clear example of the complexities of Polish grammar.

Case |

Example | |

| Nominative case | To jest Bill Clinton. | This is Bill Clinton. |

| Accusative case | Lubi? Billa Clintona. | I like Bill Clinton. |

| Genitive case | Szukam Billa Clintona. | I’m looking for Bill Clinton. |

| Locative case | My?l? o Billu Clintonie. | I’m thinking about Bill Clinton. |

| Instrumental case | Rozmawiam z Billem Clintonem. | I’m talking with Bill Clinton. |

| Dative case | Da?em Billowi Clintonowi. | I gave Bill Clinton… (s’thing). |

| Vocative case | Wzi??e?, Billu? | Did you take it, Bill? |

Because of declension, the word order doesn’t make any difference. For example, if you want to stress that you gave it to Bill as opposed to George, you could say, with the proper vocal inflection to stress it, “Billowi da?em.”

| -a is a feminine ending, so such nouns[, which are masculine nouns but in fact have feminine endings,] are declined as feminine in the singular but as masculine in the plural. Polish: An Essential Grammar by Dana Bielec, page 85 |

But learning Polish grammar is not simply a matter of remembering some endings, for all nouns in Polish have a gender (as in German, French, Spanish, etc.), so you have to learn a hell of a lot of endings.

- Three genders

- Seven cases

- Singular and plural

So when you utter a Polish noun, there are forty-two possible endings, depending on whether it’s singular or plural, masculine, feminine or neuter, and whichever case is necessary.

And the exceptions, for some forms are exactly the same except in given cases.

- The accusitive plural and the nominative plural of neuter nouns are identical, but feminine and masculine nouns are different.

- The female genetive and locative cases are the same for singular nouns but not for plural nouns.

Aside from that nonsense, there are various considerations for exceptions. Is it a masculine alive noun? Does it end in “a”?

| The genitive case [. . .] is used [. . .] For the accusitive case in (a) masculine singular/plural nouns denoting men and (b) singular nouns denoting living creatures [and] for the direct object of a negative verb[, as well as] after the number five and upwards. Polish: An Essential Grammar by Dana Bielec, page 106 |

Genitive Case

My favorite case (I never thought I’d say that) is the genitive case — it shows just how absolutely, astoundingly, and weirdly arbitrary Polish grammar is.

To being with, the genitive case is used for the direct object in negative sentences (as opposed to the standard accusitive). In other words, if you say, “I don’t like cabbage,” the form of “cabbage” would be different than in the positive sentence, “I like cabbage.”

| Lubi?kapust?. | I like cabbage. |

| Nie lubi?kapusty. | I don’t like cabbage. |

It is also used for quantities of five and above. That means there are two plural forms. If you say “I ate two dinner rolls,” you use one form; if you say “I ate five dinner rolls” you use a different form. In English, it would be like saying, “Martin has four brothers.” “No, he has five brotherid.” The “dinner roll” example in Polish looks like this:

| Zjad?em jedna bu?ke | I ate one dinner roll. |

| Zjad?em cztery bu?ki. | I ate four dinner rolls. |

| Zjad?em pi?c bu?ek. | I ate five dinner rolls. |

But that’s not all. Once you get to twenty, it’s only for numbers that contain the actual with the word “five,” “six,” “seven,” etc. that use the genitive case. Returning to the dinner roll example, we see how the plural form switches back and forth:

Quantity |

Form |

| 1 – 4 | bu?ki |

| 5 – 20 | bu?ek |

| 21 – 24 | bu?ki |

| 25 – 30 | bu?ek |

| 31 – 34 | bu?ki |

| 35 – 40 | bu?ek |

Given all there is to think about, it’s no surprise that I once compared my speaking Polish to clear-cutting a forest, or strip mining.

Verbs

All Polish verbs come in pairs: an imperfective and a perfective form. The imperfective form is for actions not completed or for regularly occurring actions; the perfective form is for completed actions and one-time actions.

It’s like an attempt to make up for Polish’s lack of tenses, for Polish only has present, past, and future tenses. (English has twelve tenses, mind-blowing for beginners in Poland.) For instance, using the imperfective form in the past tense is equivalent to using past continuous in English: I was doing something (i.e., an interrupted, incomplete action).

The forms themselves can get crazy. The future tense of the imperfective form is created with the future form of “be” (i.e., “I will be” in English) with the past form of the imperfective form of the main verb itself. In other words, you literally say, “I will be went” in Polish, which is why that particular, odd construction appears often with Polish learns of English.

The perfective/imperfective pairing is all fine and good, but what it means from a practical point of view is that learners of Polish have to learn twoPolish verbs for every one English verb. Often they’re quite similar. “Do” for example is “robi?” in the imperfective form and “zrobi?” in the perfective form. But some of them are completely different:

| Imperfective | Perfective | |

| to find out | dowiadywa? si? | dowiedzie? si? |

| to leave on foot | wychodzi? | wyj?? |

| to take | bra? | wzi?? |

| to watch | ogl?da? | obejrze? |

| (How the hell do I pronounce all that?) |

Polish verbs, like verbs in French, German, Spanish, Italian, etc., change their form according to the person. English does too, but only in present simple: “I go” but “He goes.” In Polish, they all change. For present tense there are twenty different verb ending patterns, though they are, by and large, similar. For example, almost all first person singular (“I”) verbs in Polish end in “-?” or “-am.” Almost all third person plural forms (“they”) end in “-?” with some of the adding a “j” before it (i.e., “-j?”).

The past tense is another story altogether, for its forms are gender sensitive. For example, the first person singular form for a man takes the ending “-?em” and the first person singular form for a woman takes the ending “-?am.” The stem for this comes from the third person singular present tense form. It would be like taking “goes” in English and adding “-ed” for a man and “-eda” for a woman. Sam would say “I goesed” whereas Samantha would say “I goeseda.”

Occasionally the stem even changes between masculine and feminine forms. Stem for “go” in the past for a male is “szed” whereas for a woman it is simply “sz.”

The full pattern is:

Past Tense Conjugation of “i??” (“go”)* | ||||

| Singular | Plural | |||

| Masculine | Feminine | Masculine | Feminine | |

| First person | szed?em | sz?am | szli?my | sz?y?my |

| Second person | szed?e? | sz?a? | szedli?cie | sz?y?cie |

| Third person | szed? | sz?a | szedli | sz?y |

| * Literally “i??” is “to go once, by foot.” |

In the plural forms, the feminine conjugation is used only when there areabsolutely no males in the group. One male, and you have to use the masculine form — a reflection of Polish society’s highly patriarichal standard.

Oddites of Polish Vocabulary

- The words for “sky” and “blue” are related. Nothing particularly odd about that until you take into account that “heaven” and “sky” are the same words in Polish: niebo. This means that in church, when the priest makes reference to “our heavenly father,” he’s also saying, “our blue father.”

- The words for “lock,” “zipper,” and “castle” are all the same:zamek.

- “Wódka” (pronounced “vood-ka” — “vodka,” obviously) is related to the word “woda” (“water”) and could be translated “water-let” (as in piglet). (Read more)

- There are at least six words that can be translated “go.” The difference lies in three factors:

- is it a habitual journey or a one-time affair;

- is it by foot or by vehicle;

- is it a completed action or not?

- The word for “door” (“dzwi,” pronounced “jrvee”) exists only in the plural form, like “trousers” or “scissors” in English (which, too, exists only plural in Polish). Other only-plural examples include the Polish words for:

- birthday,

- ice cream,

- holiday,

- back (i.e., part of the body), and

- rake.

- The words for “pigeon” and “dove” are the same, resulting in students coming up with an interesting construction: Pigeons of Peace.

The Other Hand

One great thing about Polish is it’s phonetic. There are some similar-sounding letters (for example “ó” and “u,” or “?” and “si”), but by and large, you don’t find the nonsense you find in English, where “g” pronounced like “j” one time, and like “g” another.

Similarities

For a language that likes to cluster a lot of consonants around a single vowel, Polish has a lot of word pairs in which the meaning is quite different (even completely opposite), but the orthographic difference is a single vowel, often simply the addition of “y”:

| Polish | Pronunciation | Meaning |

| przesz?o?? | pshesz-woshch | past |

| przysz?o?? | pshisz-woshch | future |

| wej?cie | vay-shche | building entrance |

| wyj?cie | vi-shchhe | building exit |

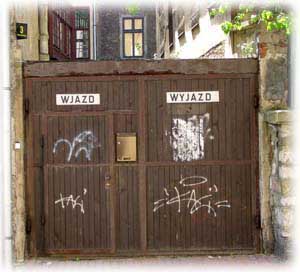

| wjazd | vyazd | vehicular entrance |

| wyjazd | vy-jazd | vehicular exit |

| wyk?ad | vi-kwad | lecture |

| wk?ad | vkwad | refill |

The most troublesome is przesz?o?? // przysz?o?? — when explaining grammar in Polish to first year students, one slip of the tongue and suddenly you have some momentarily confused students. “But I thought this was a pasttense, not a future tense!”

Of course if you’re driving, wyjazd/wjazd might be disastrously confusing . . .

All quotes are from Polish: An Essential Grammar by Dana Bielec, as well as details about declension. (You don’t think I could have written all stuff off the top of my head, do you?! I can’t remember all the details, and that’s why I speak Polish like an idiot.)

Information about verbs comes from Prawie Wszystko o Czsowinku (Almost Everything About Polish Verbs) by Dorota Drewnowska and Ma?gorzata Kujawske, as do the declension examples with Bill Clinton.

Both are excellent resources.