E on a Bridge

I forget about it before every visit, but it’s the one thing I have the most trouble adjusting to when going to Poland in the summer: the sun rises ridiculously early. Part of this is because of how far north Poland is, and part of it is how far east it lies in its time zone.

When we arrived, the sky was turning bright well before four and the sun was shining brightly by a little after four. For someone like me who has great difficulty falling asleep when there’s significant light at all, this sleep blinders or some creative alternative.

This morning, I woke up, saw that there was no light coming through the window, remembered I was back in America, and realized I had no idea what time it was. I was fairly well-rested and didn’t feel as if I’d awakened after a short doze. If I woke up like that in Poland, I would know it was probably two or three in the morning.

I glanced at my watch and seeing that it was six thirty, realized I probably wouldn’t be going back to sleep. For my body, it was noon. Sure, I’d going to bed at something like five in the morning body time, but I guess noon was the latest I could sleep. And the same went for L. And for E. Which meant that it soon enough meant the same for K.

We always leave with such mixed feelings. On the one hand, everyone is looking forward to a return to normal rituals in normal places — to a return home, in short. And yet, who really wants to leave Babcia? Who wants to leave a place filled with incredible paths for bike riding and adventures around every corner? Who wants to leave a place that is at the same time comfortably known and yet always new?

The final evening is filled with those bitter-sweet moments. We say goodbye to so many people, and we stand in the cool evening, kids playing, and chat as if it were just a normal evening in a normal summer — nothing out of the ordinary. Just friends and family catching up on old and new times.

We all pretend it’s just another departure, but it never is. A lot can change in two years. The little girl that L began treating like a little sister — playing with her, protecting her, hugging her — will no longer be the little girl she is. She’ll be closer to E’s current age. The neighbor girl L played with will be well into her mid-teens and perhaps not so thrilled about hanging out with a twelve-year-old.

All of this weighs heavy on Babcia, but she doesn’t really say that much. Occasionally she comments on how sad it all is, running off back to the States after such a “short” visit. It’s tough on her, I’m sure, returning to a virtually empty house, with just the regular noclegi guests, but she keeps it mostly to herself.

We go to bed a little worried about connections tomorrow. We arrive in Munich with only an hour and fifteen minutes to make our connection. In the past we had hours. Now, we’re cutting it terribly close. There are certain advantages to that: we don’t have to get up before we go to sleep in order to make the hour-and-a-half drive to Krakow. Yet that buffer — I’m a little worried having kids in tow. Still, if we land on time, we should make it.

The first fall was nothing to worry about — a simple matter of losing momentum in an area where it’s challenging to regain it. Tall grass, a bit of an incline. I’m not surprised he fell. He cried just a little bit, but he managed to calm himself and ride on anyway.

The second fall was more serious. We were riding in one of the two wide tracks a tractor leaves in the fields of grass when he suddenly hit a small clump of grass that didn’t give way but instead insisted on twisting his front wheel violently to the right. His bike stopped without warning, and his little belly slammed into the stem. This time, there was quite a bit of crying. Still, I managed to calm him with our deep-breath methods.

“Take a deep breath,” I say, and he breathes in through his mouth with a quivering breath, then lets it out. Two or three times and he’s usually calm, usually past the crying.

My question was simple: will he continue riding. We’d already made it to the river and were heading, against his initial wishes, to the small concrete bridge just a bit further up the trail. Here he was, hurt, scared, crying. Would he continue?

He did. He accepted my advice to slow down just a bit and continued on.

“I’m proud of you,” I said, and trying to reorient it to his own point of view, rephrased it, “And you should be proud of yourself.”

The third fall was a bit more serious. We’d made it to a part of the path that was particularly challenging: low-hanging branches, deep ruts filled with mud. I walked my bike across and suggested he do the same. I was both worried and proud when he decided that he would try to ride through the pass.

He made it through the mud, but just barely. He came to a sudden and unexpected halt beside my bike, them promptly fell toward my bike. His upper arm landed perfectly on the largest cog of my crankset. It could have been a lot worse: in the end, he had a little scratch where his arm slid off the crankset with a long streak of grease on his arm — I haven’t exactly cleaned my chain adequately since arriving — and a long crying session.

What impressed me most was that in each and every situation, he got back on the bike and continued riding. Nevermind that the bike is a piece of junk we bought for him used at the jarmark. Nevermind that he was in real pain a couple of times. Never mind that he’s only five years old. He kept on going, knowing the challenges ahead of him (for this was the second time we rode this path) and fully aware of the pain he was experiencing.

In the evening, I took a walk back up to the high fields to the north of Jablonka. I’ve ridden my bike there a couple of times — and there is a passage that I had to walk due to the steep slope and the size of the gravel (or should I say boulders) that made up the path — but that was always without a real camera. The clouds were just right, and I thought I’d give it a try.

The sun was still too high for soft, embracing light, but I took what I could get.

I reached the summit and noticed in the direction of Lipnica an enormous amount of smoke. Perhaps someone burning the fields? It’s illegal, but people still do it. But in late July? Unlikely.

As I walked toward the smoke, hoping with my super-zoom to figure something out, the siren at the Jablonka fire department began wailing. Shortly after that, the rescue truck seemed to crawl toward Lipnica, and for a moment, I considered jumping in our borrowed car to see what it could be. It wasn’t fields, but the smoke was so white that I wondered what it could be.

On my way back home — which led by a house I’d noticed a couple of weeks ago, with a fountain in the front yard that reminded me of the conclusion of Analyze This — I saw several over the firefighters standing in front of the station. I thought about stopping to ask what had been the emergency, but in the end, I just walked on. After all, the Boy as waiting for a promised game of soccer.

It usually happens in the opposite direction: Slovaks come to Poland for the relatively cheap goods here. Twenty years ago, Poles went to Slovkia, but now that has reversed since Slovakia adopted the Euro. However, Babcia likes bucking trends, I think, so today we went, as we always do during our stay her, on a shopping trip to Trstena, the nearest town in Slovakia.

Every time we go into Trstena, Babcia waxes romantic. She goes on and on about how she loves the town, about how there’s so little traffic compared to Jablonka, how there are so few plastic, awful sign attached to every available surface.

It is a unique little town: you can stand in the middle of the town square and just behind a few buildings see the farming fields.

It’s a sliver of town in the middle of vast fields of grains and grasses.

It’s a small town, but there are a couple of churches and several restaurants.

It’s easy to see how a small town could support two churches — at least in the past. But so many restaurants? There can’t possibly really be any industries around here, one thinks. And then one remembers the fields surrounding the town. And who knows — perhaps they are like their neighbors just across the border and go abroad to work.

We started with the shopping. Babcia is convinced that Slovakian flour is better than Polish flour, so we bought an almost unbelievable amount of flower. The next item we bought in large amounts was Slovakian rum. Slovakia is not exactly the first country that comes to mind when thinking of rum, but Babcia swears by it. Finally, we almost emptied the store of the grill rub that makes chicken wings magical for the Girl.

Every time we come to Poland, I find myself searching for little corners that are just like I remembered them in the mid-90s when I first arrived in Poland. Truth be told, they’re harder and harder to find. Poland has changed so much in the last twenty years that even familiar streets seem somehow new.

This weekend, I went to Nowy Targ to visit with an old friend, probably my oldest friend in Poland. We wandered around NT reminiscing, looking, at my request, for little spots that still look just like they did in 1996. For the most part, what remains are elements. whispers and shapes of the past buried here and there.

The “Dom Handlowy” (“House of Trade” you might translate it literally, but in reality a department store) has received a complete remodel. But it still has traces of its past.

“The sign is the same one, I think,” said my friend. If it’s not, I think they at least recreated it with an almost-identical design.

Some street corners look just like I remember them, or if I don’t remember them, just like I would imagine them to look in 1996.

But other things have disappeared. The nearly-ubiquitous Maluch has all but disappeared from the roads, and only every now and then makes an appearance as a novelty item at a wedding.

Every now and then you stumble — literally — on an old sidewalk, made of concrete squares that over the years have settled unevenly to create something that only in one’s most generous moments could one call a sidewalk.

Tractors are not as common on the town streets of NT as they once were, but every now and then, you see one. I doubt there are any more horse-drawn wagons delivering coal in the winter, but perhaps if you looked diligently enough, you just might find one.

One thing has not changed, though. Not at all. Not in the slightest: the movie theater in NT.

Top to bottom, left to right, it is absolutely the same. The dated architecture, the tired signs with failing neon, the crumbling corners — it’s just like I remember it from 1996.

My friend’s wife explains that it hasn’t been renovated because it used to be a synagogue, and various groups are preventing renovation. But it doesn’t look like a synagogue in any way. At all.

Yet a little searching on the internet reveals this:

Podczas II wojny światowej Niemcy zdewastowali synagogę. Po wojnie zniszczony budynek powrócił w ręce reaktywowanej gminy żydowskiej, jednak wkrótce przejęły go władze i otworzono w nim kino „Tatry”, które działa do dziś. (Source)

And this, from the theater’s own web site: “Nowotarskie Kino Tatry istnieje w zabytkowym, przedwojennym budynku, w którym kiedyś była… żydowska synagoga” (Source).

Certainly if Jews of the early twentieth century came wandering around present day Nowy Targ, they would see even less that they find familiar.

For a couple of days and the night between, we have a house full of girls. Four girls, five if we count Babcia, who’s always going to be a girl at heart, I think.

At first, it starts out as something of a perfect storm of a day. It’s freezing cold — 12 celsius, 53 Fahrenheit — and raining. The girls, it appears, will have to find entertainment indoors. First entertainment: dish washing. Eight hands, one sink, though — it won’t work for everyone. Division of labor: the older girls wash, the younger girls, well, play.

“That’s not fair.” My own kids can almost immediately predict my response: life seldom is. As for the others — they reply similarly. Must be a parenting thing.

Finally it warms up a bit and, more importantly, the sun comes out.

We all head out for some fun.

L gets busy trying to make the arrows K bought for her at odpust useable. They mysteriously have a dangerously sharp arrowhead but completely lack any nock. The girls get the sharp arrowheads taken care of but have a bit of difficulty adding the nocks. In the end, they test fire one, decide it’s not worth it, and go off to look for other things to entertain them.

They find it soon enough.

An enormous dragonfly. We immediately get into a discussion as to whether dragonflies can bite or sting or not.

One thing that can sting, of late, is E’s soccer kick. He’s really grown to love the sport while here in Poland — he sees all the boys playing it everywhere and he’s decided to give soccer another chance in the autumn. Babcia’s kick is nothing to joke about either. At one point she kicks it powerfully into the bottom of the balcony and sends bits of plaster flying.

After dinner, a walk into areas of Jablonka I’d never been to until recently. They’re certainly not new areas: some of the houses have the evidence of the village’s growth: old house numbers when it was enough to write “Jablonka” and a number on an envelope to get mail to a resident.

And like every village, I would imagine, mysteries, like a gate without a fence. Did it fall? was it simply the wire fence just behind it?

And there are other mysteries, but more in the sense that the Catholic Church uses the word: things that seem impossible and are in fact reality even though the exact mechanisms might not be known. For example, an abandoned barn in the middle of a field.

One corner of the foundation was surrendering, letting the whole structure sag toward that weakened point. Yet it’s likely not as old as one might think. The shingles are the same asbestos-based shingles that Babcia and Dziadek had on their house, built in the eighties, until just a few years ago.

Finally, a modern rural Polish mystery — again, in the Catholic sense. Here’s a building that’s erected just in front of the old barn. In the front half, there’s a clothing store called Ela, which is a “fashion and style” shop. In the back half, a shop selling “windows, doors, gates, and blinds.” The owner of the barn opened two shops? Opened one shop? Built the building and rented the space?

It’s probably only a mystery to me, an outsider.

The Girl is in Spytkowice, a village about twenty minutes up the road. (That’s the American in me, giving distances in time and not kilometers, in this case.) That means no jarmark unless the Boy and I want to go. And we really don’t want to go. We want to sleep. Since K has headed back home, he’s been sleeping in my bed. “He kicks all night!” L explained many times and then begged me to take over the evening duties. So now he sleeps with me. And that somehow that helps him sleep a bit longer than he might normally.

When we get up about half an hour later than usual, it’s time to help Babcia gather the raspberries in the garden. The Boy willingly wiggles into the spots that are just his size.

Afterward, we take a ride to the river. We’ve walked there many times, during this visit and past visits, but we’ve spoken several times about riding our bikes there, but it was only today that we manage it. In the end, we ride a little over five kilometers and get some fantastic views along the way.

But riding with the Boy, no matter how much I enjoy it, is not much exercise, so when we get back to Babcia’s house, I head out for another ride. This time, I head back to the Lipnica area, cutting through fields and following the ruts worn by years of tractor traffic.

There are a few impressive views along this ride, too. So much has changed, though, and yet nothing has changed. I make my way up Lipnica Mala at a leisurely 22 kilometers per hour. Years ago, I used to roll up the same road at around 28 kilometers per hour. Or at least I think so. It sounds good at least to say that.

At eleven years old, cousin S jumped on a bus at ten in the morning and rode half an hour to Jablonka to spend the day with L. And what did they do? Sew. Sort of.

At times, it was a bit of a mystery what exactly they were doing, other than enjoying a rainy, gray morning.

After lunch we headed to Lipnica, my home seven years and K’s home for one. It’s now twenty-one years since I first arrived in that eighteen-kilometer village, and some things have changed beyond recognition and something are exactly as they were in 1996, or even 1986, or perhaps 1976.

The school in which I taught, which was so very new when I arrived (it was only a year old and not even completed) now is beginning to show its age. It looks old, to be honest. It looks a little neglected. It looks like every little has been done to the outside since being built. Somehow that seems about right and out of place at the same time. Poland is in such a state of development — so many new buildings and such — and yet, buildings built in the mid-90’s? They seem somehow to have fallen into disrepair. They look like, in a few years, they’ll look like the buildings I became so accustomed to when I arrived 20+ years ago. Tired, out of date, yet still functional and functioning.

And some things have not changed at all. This house looks exactly like it did four years ago, exactly like it did in 1996, and that was probably how it looked in 1986, and it might have even looked like that before then. It’s eternally surowy, raw, unfinished.

Other things — I never noticed.

What are these ruins? What was here before? Were they always like this? It’s right beside the school where I taught for seven years, but I saw it for the first time today.

This too.

It’s a century-old house (at least) but it looks like someone tried to renovate it — clearly didn’t know what they were doing. Or perhaps I’m totally wrong. Still, I don’t remember it. And what does that mean? Very little, I’m sure. But we always place such a premium on what we remember…

This I remember. But the roof — it’s been renovated. Gone are the asbestos-based shingles that had probably been there, what? Thirty years? Forty? K’s parents replaced their asbestos-based roof more than ten years ago — what took them so long? After all, this was the GS-owski shop. Things have simply changed — that’s all.

All except for children and their willingness to be silly.

They say there are no atheists in foxholes, but more obvious is the fact that there are no strangers in foxholes. I’ve read that in high-tension battle situations, soldiers are not fighting for any sort of grand patriotic notion but simply to protect the men beside them. Challenges bring people together, in short.

I saw that myself a week or so ago when L and I together went through the toughest course at the local line park. We bonded in a way we hadn’t ever really done before.

Today, though, instead of experiencing it, I witnessed it. We went back to the line park with S, L’s and K’s cousin, who was a little hesitant at first about the whole idea. S is not really like L, who will dive into some things without thinking. S is a bit more hesitant. So when I suggested this morning that we might go to a line park after lunch — if it stopped raining — her first reaction, other than, “What’s a line park,” was hesitant. When L and I explained what it was, her reached changed just a little — up went the eyebrows.

“Maybe…” was all we got.

In the end, she agreed, and in the end, she loved it. And in the final count of things, she agreed that it would be fun to try it again.

The Boy, though, is not big enough to go on any of the courses except the “Junior Course.”

But there were a couple of things that everyone was eligible to do.

First, the Boy decided he wanted to help Babcia with the rosol. After making the broth of chicken, duck, and beef, she adds vegetables, and the Boy always loves helping in the kitchen.

“Babcia, do you have a cutting board?” he asked, and before she knew it, he was carefully cutting the bits of rejected cabbage and other veggies.

Afterwards came the walk — but first, the Boy had to open Babcia’s tricky back gate.

Out on the walk, I decided we needed to change things up. Instead of heading straight to the river, we turned left where we normally continue straight. I had a feeling we would end up on the other side of the river, but E was lost. Until we saw the river a little bit later. Then crossed a bridge over the river. Then saw the spot at the river we normally visit — only from the other side.

The dog of course enjoyed all the puddles

A clothes drier is a standard item in the States. I don’t know anyone who, having a washing machine, doesn’t have a drier. That’s simple enough to understand: electricity and gas are both cheap in the States, and driers are almost always packaged with washers. In Poland, though, it’s a different story.

In much of rural Poland, gas lines simple don’t exist: all gas products use propane tanks. And as far as electricity goes — forget it. It’s ridiculously expensive compared to what we pay in the States. Bottom line: Babcia doesn’t has a drier, and that means one thing — there’s a lot more ironing going on in Babcia’s house than in our house. Everything — jeans, tee-shirts, underwear (and I’m not joking here; some people do iron their underwear), bed clothes, everything — gets ironed.

With all the additional clothes, that would be a ridiculous amount if work, so we try to iron as much as we can. (I say “try” because Babcia is liable sometimes to pull everything off the lines and iron it all while we’re out hiking or some similar silliness.)

Today, E learned to iron. L insisted that she knew how to already, and when she began ironing her own clothes, it seemed that she did indeed know how to. The Boy, though, needed lots of instruction. They both need a lot of work with folding, though.

The outcome: after a few minutes, they were fussing and arguing over who got to iron.

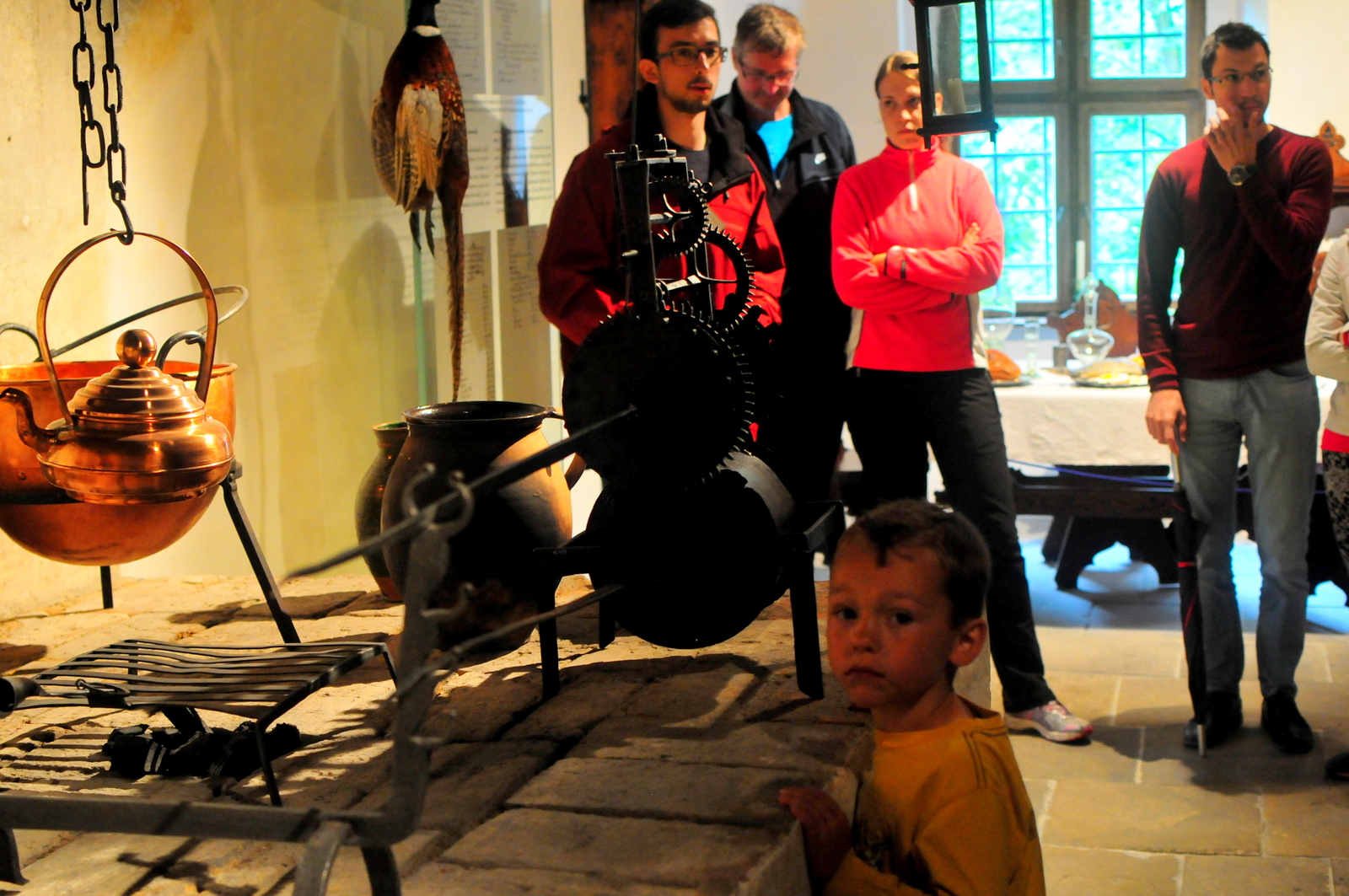

A fourth (or is it fifth? or third?) visit to Oravsky Hrad. This time, a few changes. A simplified camera set up to accompany a simplified tour due to the ages of our tourist. And a few random thoughts that unwound along the way.

In the crypt of the chapel at Orava Castle there are three coffins, two small ones and a large one. The tour being in Slovak and only partially comprehensible to me, I’m not sure if I understood it all, but I believe the two coffins are those of one owner’s children, an eight month old and a four year old. I had one of those moments: I remember what family life used to be, even for the riches and most fortunate. Infant mortality was unbelievably high (compared to now), and even living past five or six was not assumed. Having children might mean burying them before they were a year old, and it might mean burying multiple children. They could have died for any number of diseases that have now been virtually eradicated through improved hygiene, a better understanding of disease and its transmission, and effective vaccines. Yet for them, each child’s death was something of a mystery. Sure, they recognized and categorized diseases based on symptoms, but the actual cause was a mystery, as was any possible prevention.

And so I am grateful that I live in a time when protecting my children against measles, for example — a potentially fatal disease that, according to the WHO, would have resulted in “an estimated 20.3 million deaths” between 2000-2015. I’m grateful that I live in a time when I can take my child to the doctor and get a diagnosis and medication to help the child. I’m grateful that I’ve never once wondered whether my children will die of measles or small pox before they turn five. As I looked at the smallest casket, I felt fairly sure that her parents would have given almost anything to have that kind of security.

Orava Castle was the set for Nosferatu, a 1922 film adaptation of Dracula. I remember hearing that the idea of a blood sucking tyrant came from Vlad the Impaler. Here was a man who could do just about anything to just about anyone and became famous for a particularly brutal way of killing. He seems to be the exact opposite of what we have in most countries in the Western world today, where the rule of law treats everyone — theoretically — the same. Anyone from a homeless person to the President of the United States can be subject to the same law.

Yet what is most surprising about Vlad is that he was a real law-and-order guy. While there were plenty of people who were killed for arbitrary things, a great number were killed due to transgressions of Vlad’s severe moral code.

Further, Vlad was involved in fighting the Turks and preventing the spread of Islam in Europe. Despite his brutality, he was considered an orthodox Christian, and the Pope had little to nothing to say about his viciousness. He was, after all, fighting the Turks — the rest is insignificant, right?

When the Turks’ invasion began overwhelming Vlad’s forces, he began a scorched-Earth policy, destroying villages on both sides of the Danube to slow the Turks’ progress. This meant destroying his own people in vast numbers.

And so I began thinking about how we take this for granted today. We don’t raise our children wondering whether or not our own leader is going to slaughter them trying to save his own power. We don’t have to fear our rulers’ whims because they are subject to the same laws we are.

Tour Guide

Oravský Hrad

I’ve often mentioned how we tend to repeat things during our visits to Poland. The island in Slovakia that we visited yesterday–countless times. The castle we might head to tomorrow if weather turns bad–many, many visits. The line park in Zubrzyca Gorna–who knows! In some cases, like the line park, it’s just because we like it. Or rather, our kids like it. Sometimes it’s because of taking various visitors to certain sites. And sometimes, it’s just because we think it might be good for our kids to experience it once again at an older age.

Today’s adventures included all the above.

We went back to Dolina Chochołowska, a valley that runs through the Polish Tatras just at the border of Slovakia. It’s a place where you can see some incredible views, soak your feet in some frigid mountain water, and get enough exercise to exhaust almost anyone.

In short, we did ten miles today. The “we” consisted of two grown men, two five-year-olds, an eight-year-old, and a ten-year-old. The two youngest trekkers made the vast majority of the trip on their own. E rode one my shoulders for perhaps half a mile, maybe a little less, perhaps a bit more. But the vast majority of it, his little five-year-old, short legs carried him. Willingly. Without fussing.

The Girl was a fussing mess the last time we hiked Dolina Chochołowska four years ago. Today, the only worries came when, during a break, she slipped off the rocks where she was playing and got her shoes wet. But even that was only a momentary set-back. She took her socks off and continued the rest of the way (probably four more miles) in wet sneakers with very little complaining.

As usual, click on the pictures for a larger version:

The Girl didn’t make it the first time around. She reached the penultimate obstacle — an incredibly long zip line — and she quit. Did she reach her limit or did she give up? I don’t really know, given today.

This afternoon, we headed back to the same location, and I put on my tennis shoes and tackled the same course with her.

I think it’s the most fun I’ve had with my daughter in years.

To begin with, she was incredibly helpful. With each obstacle, she explained what was challenging about it and how things went the last time.

“Daddy, this one is really hard — you might want to use the zip line like I do.” I refused, and within a few moments, thought, “That young lady had a good idea after all.” The two obstacles that she suggested this for were so muscle-screamingly exhausting that I realized if there were more like that, I might not make it myself.

At the end of each obstacle, she was there to offer a hand.

“I’ll hold this last one for you, Daddy, to keep it still.”

More importantly, though, she was a different young lady. I don’t know if it was my presence or the fact that she was tackling the course for the second time, but she was incredibly confident. The portions of the course that gave her so much pause last time warranted only a quick caution and explanation.

A few hugs along the way helped as well, I’m sure.

No photos — for the first time, the camera stayed in the car the whole afternoon — but a friend shot some footage for later use.

What did I use the camera for, though? The jarmark, of course.

There’s a funny scene in Miś, my favorite Polish film, in which a broken down tram line turns into an occasion for entertainment — literally. A program of singing and such prepared before the breakdown in the event of a breakdown.

It was, I think, a parody of the ruling party’s ability to turn anything into a “celebration.” That continues today, I think, with Miś-like similarities. When K left yesterday, there was a band, priests, politicians, news reporters, photographers, various people in formal dress, all for the occasion of K’s flight’s departure. The first direct flight from Krakow to Chicago in some time — maybe ever. I don’t really know. It doesn’t really matter. What matters is that it was a big deal for some people.

While waiting in line to check in, K was interviewed. “Watch the news,” she told her mother later, “I might be there.”

What an occasion!

Except that the departure was delayed over an hour. And that deal cost K (and her traveling companion, U) their connection in Chicago. Which meant a wait over almost eighteen-hours for the next flight.

“See?! I told you guys not to fly LOT,” proclaimed B. perhaps she’s right.

K’s stay is coming to an end. On Monday, she flies back to the States with U, her best friend’s daughter, and we stick around for another three weeks. Today, though, was her last full day here in Jablonka, and as usual, she tried to accomplish a million and one things.

Lunch was easy — a trip to what was fifteen years ago the only real restaurant in Jablonka. Then a short visit to the appliance shop down the street.

It must be a late-June/early-July weather acclimation thing. Or maybe it’s halny. Or maybe — likely — it’s just coincidence. At any rate, it’s late June, and we’re in Poland, so that means we head to Babcia’s ancestral village, Zab.

In 2008, it was July 9.

Tooth

In 2010, it was June 28.

Ząb

In 2013, it was July 1.

Visiting Ząb

In 2015, it was June 28.

Ząb 2015

And in 2017, it was June 29.

Out of our five visits, then, there’s one outlier, and only by a week. Whatever the coincidence, it’s always an enjoyable highlight of the visit to Poland. But the day didn’t quite start out as auspiciously as it ended. It began like you might expect a day in the village to begin: with a lot of work.

When we arrived last night, we discovered that Babcia had taken delivery of enough kindling for, as she explained, three or four years. And at least a quarter of it was lying in the road because the tractor that delivered it couldn’t maneuver any closer. So we got to work segregating and hauling various pieces of wood from a woodworking shop, wood of so many sizes and shapes that it was almost overwhelming. This morning, we got to work cleaning up the final bits.

(Click on images for larger view.)

We all pitched in. E was in heaven, for he loves doing anything work related. L has always been less excited about work, but she helped like the rest of us with no fussing, no concerns but one: “What will Babcia the next time she gets wood and we’re not here?” Growing up in more ways than one, that girl.

(Click on images for larger view.)

The trip to Zab itself was as it always is. We stop by the most beautiful cemetery in the world to clean up Babcia’s mother’s and father’s grave and pay our respect, head to her sister’s house for incredible cooking and even more amazing conversation, walk across the street to her brother’s house for a second helping of everything, and end at Furmanowa, where one can undoubtedly find the best views in Poland.

(Click on images for larger view.)

There’s nothing more to say because I’ve already said it several times over, and therein lies the perfection.

Changes are everywhere in Poland. It’s like not seeing your friend’s child for two years and then being surprised at how much bigger she is (which is a common occurence during each visit here, for both us and our local friends).

Nowy Targ, for example, was not a city that would immediately come to mind as an answer to the question, “Where is the nearest nice park?” I went there a lot while I lived here, as it was the nearest city and another American lived there with whom I became good friends. If I wanted to get contact solution, I had to go to Nowy Targ. If I wanted to speak English without worrying about what vocabulary I was using, I had to go to Nowy Targ. If I wanted to watch a movie or eat in a restaurant, I had to go to Nowy Targ. If I wanted to commiserate with someone about this or that apparent Polish absurdity (I complained a lot in my twenties. I still do, but not nearly as much…), I had to go to Nowy Targ. But it was not a place that would make sense to say, “Hey, let’s take the kids to that great park in Nowy Targ.” And now it is.

A lovely park with pedal-cart rentals for the kids, nice benches for tired adults, workout-stations for more energetic adults, giant chess boards for chess lovers, shade, sunshine, flowers, trees — just about everything a little park in a little city might need.

Later, talking to a friend, I mentioned that I don’t remember it being there at all.

“That’s because it wasn’t, at least nothing worth mentioning.” But thanks to some European Union funding (I’m guessing here, but it’s a likely source), there’s a nice park by the river just beside the ice rink in Nowy Targ. Who would have thought?

But even twenty years ago, Nowy Targ had the best ice cream on the planet. And they had a market square, but without the fountains for kids to play with and all the open spaces. Just a big parking lot, more or less. EU funding again? Most likely.

The main purpose of the NT trip was to see C, with whom I played more pool and watched more movies and chatted more hours than just about anyone in Poland — certainly during the 1996-1999 stint.

But more on that later…