More playing in Photoshop. I turned this

into this

using only a few layers.

More playing in Photoshop. I turned this

into this

using only a few layers.

Routines, it turns out, are easily formed. It only takes a few mornings of waking alone, eating breakfast alone while glancing through the news on the Internet and sipping coffee, and enjoying the peace of a quiet morning. Only a few mornings of this and it becomes a new routine, replacing the old. On the other hand, it only takes one morning of noisy breakfast preparation, of kids laughing, fussing, and playing—only one morning and everything returns back to normal. The Saturday morning ritual conversation with Babcia through Skype, with the kids downstairs while I sit upstairs reading the news and sipping coffee, falls back into place as if we’d been doing it all summer.

As you emerge from the tunnel that passes under the intersection of Westerplatte, Pawia, Baszowa, and Lubicz streets in Krakow, you emerge into a green park that surrounds the old city center. All tourists who arrive from a train or a bus must walk this way, and it’s the logical place for buskers, solicitors, and beggars to line the wide sidewalk and compete for attention. There’s always an accordion player or three along the way, numerous students working for a few extra groszy by handing out fliers, and beggars. One tends to grow accustomed to them all. “Dziękuję,” you learn to say politely and briskly to the students who are near enough that you can’t simply ignore. The buskers merge with the city traffic and the general conversation to form an ignorable element of the soundtrack, unless a given performer is really gifted. And the beggars: they’re everywhere. The conscience hardens, especially when you suspect their motives. (Beginning in the nineties, some younger beggars were more honest, holding placards that simply read “Piwo” with “Beer” possibly scratched underneath for foreigners.)

But some of they get to you.

Last week, as we were walking the kids towards the old city center, we passed by an elderly woman sprawled on the sidewalk, her hands shaking violently and her medicines spread out in front of her.

“Why is she shaking?” L asked.

“She’s sick, honey,” K replied.

We took a few more steps and realized what we’d done.

“Here,” I said, giving L a couple of five-zloty coins. “Go take this to her.”

The Girl grabbed the Boy by the shoulders. “Come on, E,” she said solemnly. They went back and clanked the two coins into the small metal box that held a handful of change. Hopefully, a small, quiet lesson for them.

We had a few false starts — or at least we had a few situations where the Boy decided he wanted to go on a different trail and had to be convinced to continue on our planned trail.

We had a few situtations where utter exhaustion threatened the whole adventure.

We took a few portraits.

We took a few breaks.

We played a few games, like pretending to be asleep until a little brother approaches, then shouting “Boo!”

And of course we ate a few blueberries, though we knew we probably shouldn’t.

All the same, we somehow made it an incredible distiance, especially for a three-year-old, to the shelter, newly rebuilt, at Markowe Szczawiny.

We hadn’t really checked beforehand, but the distance from the parking lot to the shelter was a whopping eleven kilometers. That’s 6.8 miles. One way. That the Boy made it probably 70% of the way walking on his own is simply incredible.

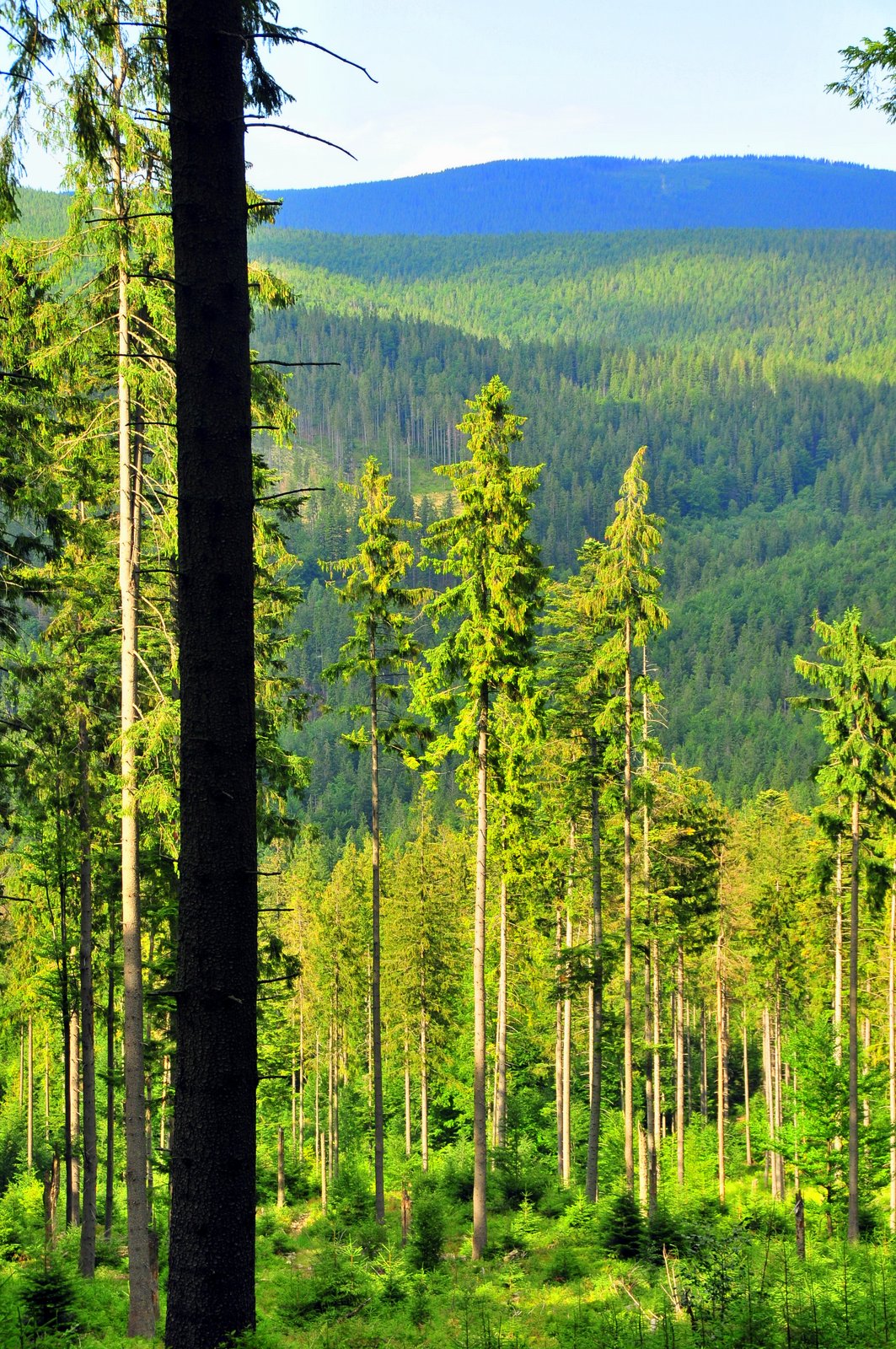

More incredible even than the views along the way.

There is a choreography to a Polish wedding and the party that follows that dictates the what, when, where, and how of almost everything. It’s not necessarily obvious at the first wedding and outsider attends, but once you make it through a few weddings, you know what to expect. They’re really not all that different from weddings in America as a whole, but in a surprisingly ironic twist, it’s just bigger. Everything is bigger. More, more, more: more food, more alcohol, more dancing, more singing, more games with the bride and groom.

To begin with, there’s the food. It’s everywhere, piled on every table throughout the whole evening. Plates of pickled veggies, cheeses, cold meats, cakes, and bowls of salads cover the tables when guests arrive, and they’re constantly replenished throughout the evening. At the end of each table stand bottles of cola, juice and water, with the center of each table reserved for bottles of alcohol: vodka (obligatory, and in various forms: clear vodka, homemade flavored vodka made with lemons or carmelized sugar, store-bought flavored vodkas — endless vodka), liquours, wines, and more. The groomsmen weave their way among the tables on a regular basis, replacing empty bottles with full from a basket of bottles they carry with them. And that’s not to mention the full meals that are served every four hours or so: plates piled high with two or three meats, some potatoes, two or three salads. Food, food, food; drink, drink, drink. It’s a cornucopia in every sense of the word.

At some point shortly after the first meal, someone will start singing. There are seemingly countless songs that every Pole knows by heart, and soon the entire room is singing in one, loud voice, with occasional harmony added by the more gifted guests. It’s a process that continues throughout the evening. Eat, drink, sing. Eat, drink sing. At our wedding, a guest brought his accordion, but accompaniment is not necessary: these are songs that Poles ingest with their daily potatoes, songs that stick to the bottoms of their shoes like the snow that covers the country through most of the winter.

Soon after the first meal and the first songs, the band strikes up for the newlyweds’ first dance. All the guests crowd the dance floor, making a circle around the smiling couple, occasionally joining hands if there’s enough room and moving around the dancing pair with swaying hands. And then come the first calls of Gorszko! Gorszko! A single repeated word that needs a pair of sentences for translation: “It’s bitter in here! Make it sweet with a kiss!” At this point, someone brings the couple two glasses of champaigne, which they drink and toss the empty glasses over their shoulders to the floor. Someone else brings a broom and dustpan, and the groom is to clean up the mess. Sometimes it’s likely that it might be the only time the groom does so, but the gender division of housework seems slowly to be changing.

And throughout the evening, thus it continues: eat, drink, be silly, dance, sing, repeat. If it’s a wedding in the highlands of southern Poland, there is even more choreography. At some point some four or five hours into the wedding, the guests gather on the dance floor for the ocepiny. Two of the grooms take the bride between them and refuse to give her over until their demands are met. These demands come in the form of a song that is often made up on the spot. A second group, called essentially “the old ladies,” reply with their own song in response to the grooms’ song, bringing some kind of gift that humorously fulfills the grooms’ request. And so it goes, back and forth, back and forth, for some time until it’s time for the “solos” — a man stands before the band (now a traditional highlander group consisting of one or two violins, a viola, and a cello to provide the bass), sings the first bit of a song he wants, then takes the bride for a turn around the dance floor. More gifts, more songs, more singing, and it goes on and on, an hour, an hour and a half.

And this all seems to combine to from a good definition of culture: a choreography that insiders seem to perform without thinking while outsiders look for the pattern. That was part of the joy of living in Poland for so long: looking for, noticing, and then learning those patterns, eventually even taking part in many of them. It’s the process of moving from the outside to the inside that makes living abroad so enlightening, for not only do you learn about your new home’s culture but you also notice things about your own culture than you never noticed before as you compare the two. Sometimes the things you notice about your own culture aren’t so very pleasant, but often having that second pattern makes the first more clear.

There’s a big difference between 100 km and 10 km, but when I began riding again a couple of months ago, there didn’t seem to be much of a difference between the two as far as my legs were concerned.

So when I took off this morning on a favorite ride, a ride I’d done seemingly countless times, I knew the ride, at a distance more than double the longest “ride” I’d gone on in the last few weeks, would be tough on me.

But the ride through Lipnica Mała to the base of Babia Góra then through the whole of Lipncia was a favorite. More than once I’d headed out for a quick ride after a day of teaching with no real idea where I was going and ended up making this loop.

With the views it was an obvious choice. Today, though, it was just as much the views along the way that fascinated me. While Jabłonka has really developed a lot, the villages of Lipnica Wielka and Lipnica Mała are relatively untouched. There are a few more houses, and some of the older houses have been renovated, but by and large, the villages look the same.

One other change became evident when I reached the end of Lipnica Mała: the formerly deeply-rutted road from the end of the village to the roughly-paved road that runs along the base of Babia was now a well-paved little street.

Of course, the forest itself hadn’t changed, nor had the sound of the wind through the trees, which sounded almost tidal.

Once I got to the base of Babia, though, I virtually forgot about the camera as I made my way up the most challenging portion of the ride.

It was at this point that I really understood, in a deeply muscular way, that my legs are nothing like they used to be.

The worst part of it is the memory, knowing that those climbs used to be no problem at all for me. I was winded at the top of several of the climbs, but I didn’t have to stop to catch my breath and give my burning legs a chance cool down. I didn’t stop and comment aloud to myself about the stupidity of the whole idea of tackling such a ride when so completely unprepared.

But somehow I survived, ate some lunch, and took the Boy out to help wash the car before tomorrow’s wedding.