Borders, 2013 — Part 2

It was a lovely spring afternoon, and I was done with school early, so a bike ride was in order. I decided to go on one of my favorites: dip down into Slovakia that loops back to Lipnica, where I lived.

Crossing into Slovakia was no problem. I made my way around Orava Lake, through Trstena and to the border at Sucha Hora (“Dry Mountain”), where I duly handed over my passport to the border guards. The Slovak guards stamped it and gave it to the Polish guard.

“Gdzie pan mieszka?” he asked.

“I live in Lipnica,” I replied.

The guard thumbed through my passport like the bloke in Mis, and then he looked at me with a puzzled look. “But how?”

At the time, I didn’t have a valid work visa: I was in the process of renewing it, following all the protocols the fine folks in Krakow had laid out, and they had assured me I had nothing to worry about. And yet here I was, on the border, starting to worry.

I explained my situation to guard, but he insisted he couldn’t grant me entry. “You don’t have a valid visa,” he said.

“Yes,” I explained, “but you can’t keep me out for that reason. Perhaps you could suggest I can’t live and work here, but you have to let me in on at least a tourist visa, which means a stamp of the passport and off I go.” I didn’t say exactly that — I used much more diplomatic terms, but that was the general idea.

“But you don’t have a visa,” he insisted, waking into his little office and punching some things up on the computer.

I stood there, dressed in my Lycra shorts and top for cycling, having only a bit of cash in my jersey pocket, and wondering what I would do if this guy seriously didn’t let me in. A friend of mine was one of the head border guards at the Chyzne border crossing, so I thought I would just ride back there. But what if he wasn’t working? How could I pull this all off? I was tired; it was nearing sunset; I had very little money. Disaster seemed just over the next hill.

The guard came back and gave me my passport, waving me through with a smile. “We’ll let you through this time,” he said, “but it would have been a different story for me if I were flying to America without a visa, wouldn’t it?” His smile grew.

“That’s what this is about,” I thought. “Someone in your family — a sister, a brother-in-law — got turned away from the States on some technicality, and now you’re having a little fun.” Naturally, I said none of this. I simply thanked him, took my passport, and rode as fast as I could over the border, which was actually another half-kilometer or so from the crossing station.

In 2013, we drove through that crossing, which was empty due to Poland’s and Slovakia’s mutual EU membership. It looked exactly as it had a decade earlier.

Zab Walk

The Neighbor

Borders, 2013 — Part 1

Random memory from the past, brought about by Lightroom playing…

Living in the south of Poland for several years, I had occasion to cross the border into Slovakia countless times. Theoretically, could have walked out of the teachers’ housing where I lived and walked across the border behind the complex in less than an hour. That would have likely been a bad idea: had I been caught…well, better not to think about it.

The nearest border crossing was down the road in Chyzne. It was a border crossing that looked like something out of a film — gray, concrete, depressing.

By the time I went back to Poland in 2001, it was all but free-passage. Border crossing took only a few minutes as opposed to over an hour if there was a long-enough line.

By the time we were living in the States and visiting only every two years, it had been torn down. All that remained was, well, nothing.

Tatra Mountains

Zab Barn

Zab Revisited

Chess in Spytkowice

M is K’s sister’s-in-law father, and he’s a keen chess player. I first played in him Krakow, at their apartment, in 2003 or so. We played one game, which lasted probably an hour and a half and went to roughly 40 moves, I’d guess. I knew I’d won with about 15 moves to go: he’d underestimated the queen-side attack I’d slowly been building.

Years later, when we went to Syptkowice to visit with them at their summer house, we’d always play. Since I’d won that first game, my ego was soothed, and I took more chances. In this particular game, those chances didn’t work out for me.

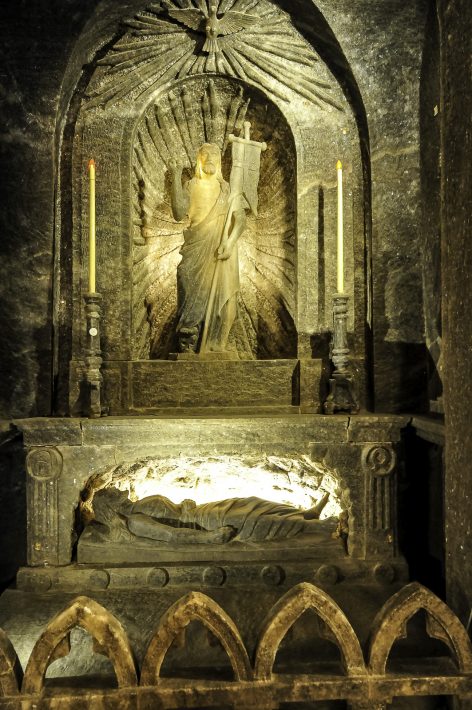

Wieliczka Revisited

Bonfire in Spytkowice

Jumping

Dinner

Spent

Chasing a Stork

Regret and Repetition

It’s early June: my thoughts always turn to an arrival in Polska. I wrote this last summer, after our return, and discovered only now that I had never posted it.

1

“Never regret anything, because at the time, it was exactly what you wanted.”

When I went to vist the school in Lipnica in which I taught for seven years, the English teacher, a former student of mine, invited me to her English lesson. As she was taking roll, I wandered about the room, looking at how the relatively new Foreign Language Workshop had been decorated. I found a poster with English sayings, including one about regret that I couldn’t recall ever having heard.

“Never regret anything, because at the time, it was exactly what you wanted.”

“So true,” I thought initially. Further thought made me wonder, though: perhaps this quote takes a simplistic view of both desire and regret.

Desires don’t come from nowhere. They aren’t frivolous imps that leap into our head, unbidden, unwanted. They arise, consciously or unconsciously, from our values, habits, and worldview. As a Catholic, I have to view some of these desires as sinful, as inherently evil. They are temptations, and I am called to overcome those temptations. If I choose not to, I’ve betrayed God, myself, and to some degree or another, my fellow humans. (After all, the Confiteor we Catholics all recite at the beginning of Mass includes this notion: “I confess to almighty God and to you, my brothers and sisters, that I have greatly sinned, in my thoughts and in my words, in what I have done and in what I have failed to do, through my fault, through my fault, through my most grievous fault; therefore I ask blessed Mary ever-Virgin, all the Angels and Saints, and you, my brothers and sisters, to pray for me to the Lord our God.” Emphasis added.) So if these desires are temptations to sin, and I give in to these temptations, and later I want to repent, how can I possibly not regret them? True, these actions were exactly what I wanted at the time, but that was because I don’t yet have a perfectly formed conscience. Further, if I don’t truly regret the sin, how can I confess the sin?

Yet not all desires are sinful desires, and yet we still end up wishing we had made different choices. Is this regret? I suppose. Is it the same kind of regret discussed above? Somehow, it seems different. Perhaps, then, we need to differentiate, look at some synonyms:

apologize, be disturbed, be sorry for, bemoan, bewail, cry over, cry over spilled milk, deplore, deprecate, disapprove, feel remorse, feel sorry, feel uneasy, grieve, have compunctions, have qualms, kick oneself, lament, look back, miss, moan, mourn, repent, repine, rue, weep, weep over

“Regret” seems the correct term for the theological notion associated with sin and forgiveness, as do deplore, lament, and grieve. For the second, less theological (and in some senses, then, less important or significant emotion), miss, feel sorry, or even rue seem appropriate. Working with those differentiations, I regret some of the sinful choices I’ve made in the past, which means I wish not to repeat them; I rue some of the poor decisions I made in the past, which means to me not so much that I wouldn’t make the same choice but that I dislike some of the consequences that came with that choice. I rued having left Poland, so I went back.

I think early in my life, I confused those two forms of regret, as do many people, I think, and that confusion as the source of the quote got me thinking of all this. In my case, I disavowed the existence of theological regret, and I overemphasized the things I rued.

2

Every time we come to Poland, we repeat: Krakow, Zakopane, even the outdoor museum in Zubrzyca (though this year, it was part of a class trip with L). This repetition is understandable in large measure because much of the repetition comes from meeting with friends and family. Yet it doesn’t change the fact that very little changes in our visits to Poland.

It occurred to me, though, the other night that part of it might be an unconscious unwillingness to move outside of a certain comfort zone in Poland. Yet that seems simplistic: it’s not as if I don’t know my way around the country and culture; it’s not as if I’m fearful of new situations here. I speak the language with passable proficiency: there are few times that I feel unable to express myself, and I even managed to talk myself out of trouble a time or two.

Yet as I wandered about the fields of Lipnica, with views I know almost better than the area in which I grew up, I wondered if it might be something else, something that I hadn’t experienced in literally years but which I knew all too well earlier in life, and multiple times at that. It struck most forcefully in 1999, when I left Poland for the first time and soon found I was desperate to return to Poland. It wasn’t that I wanted to return to the place as much as I wanted to return to that part of my life, to relive it in a sense. Returning for a short visit in the summer of 2000, I found a line from a song running through my head constantly, for I wanted to “hold on to these moments as they pass.” And so it occurred to me one evening this summer in Poland that I do the same thing every visit, revisiting places in order to relive the past, if only for a brief moment. Then that moment passes, we all move on, temporally and physically, and I find myself later reliving the relived moment again, only in my mind.

And so I find comfort in the places that haven’t changed much over the years. The exterior of the teachers’ housing block in Lipnica, for example, hasn’t really changed a bit since I first arrived in 1996. There are new windows; there is a new flue for the oil furnace in the basement; there are a few more cables strung across the facade. Other than that, though, it looks identical. It gives the illusion that, while the rest of the world has moved on, I’ve stayed the same, which is a ridiculous notion. But for a brief moment, it’s comforting.

Why?

Human time does not turn in a circle; it runs ahead in a straight line. That is why man can’t be happy: happiness is the longing for repetition.

Milan Kundera

The easy answer is that it’s a vain attempt to deny my own mortality to myself, the stuff ironically both of melodrama and of great literature. And while there might be some element of unconscious truth to that, I don’t feel I really fear death or even give it much of a thought at all. Occasionally in the last few months I’ve surprised myself with the realization that I’m now in my forties, but this is not a mid-life crisis but a how-time-has-slipped-by-so-quickly crisis. And besides, this doesn’t explain the same longing I felt — only much, much more intensely — in 1999 and 2000 that led to my return to Poland. Surely I wasn’t fretting about my mortality in my mid- to late-twenties. Only nineteenth-century poets do that.

The longing, in fact, was much simpler (and significantly more naive) than that. It arose from the fear that the past was better than the present, and worse still, that the past was likely better than the future. A bit melodramatic, I’m sure, but those were the worries and concerns I had at times. It explains a lot of the angst I experienced when younger.

I no longer feel that way at all, though. Children make it impossible to look backward with the same longing. Children make it impossible to think the past was better than the future. Children make it impossible to regret the passing of time. Hence, as I wandered the fields of Lipnica, that strange longing to return to the past, while present, was only so strong as for me to notice its relative absence in recent years.

Re-reading Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being, though, I discovered a forgotten quote that had so struck me the first time I read it that I made not of it on the slip of paper I’d slid into the back of the book and discovered as I opened it anew a few days ago. “Happiness is the longing for repetition.” Perhaps I’ve had it wrong: perhaps this repetition is simple happiness?

Children understand this simple truth: it’s why they can say or do the same thing over and over and over and over and still find it just as funny and enjoyable the tenth time as it was the first. It’s why they can swing — the ultimate in repetitive activities — for hours on end and still do the same tomorrow.

Religions understand this simple truth: it’s why all religions have ritual calendars, calling for the repetition of rituals throughout the year for all eternity.

Polish Train Ride

While we were in Poland, we took a train ride on a relatively old-fashioned train.

Explaining in Poland

I’ve only now been getting around to the videos from Poland.

Cemetery of Memories

The first time I approached the cemetery in Lipnica Wielka, it was November of 1996, and I headed up for my first experience with All Saints’ Day in Poland.

I took pictures and made mental notes for my journal:

I left my apartment around 4:30 and headed up to the cemetery to witness my first All Saints’ Day in Poland. I weaved my way through the maze of mud puddles that serve as my front yard and made it to the road, and suddenly it was if I was in Kraków instead of Lipnica. The street was filled with people, all leaving the cemetery as I made my way to the cemetery. I felt like the one Israelite who might have decided to turn back in the middle of the exodus. With my camera in hand and a bewildered look plastered across my face, I surely looked like a fool. But I didn’t care, for I was about to experience something I had heard about since arriving in Poland. (November 1996)

It was the first of many visits, for I found myself strangely drawn to the cemetery as the sun set. Summer sunsets were the best, giving Babia Gora just a touch of golden haze, but any sunset cast a lovely light over the headstones.

From the cemetery’s small hill, I could see all of the central area of Lipnica Wielka — centrum as it’s known — and that somehow gave me a sense of peace and belonging that other views lacked. Indeed, it was odd for me that from the first time I ever attended the cemetery prayers and processions of All Saints’ Day, this plot of land filled with the remains of total strangers became a place of peaceful retreat. I never imagined I’d really have a personal connection to it. After all, I taught high school, and most of my interactions were with students: how often do high school students die? All the teachers at the school were young: what were the chances of some random accident taking one of them? No, I never really thought that I would think of Lipnica’s cemetery as much more than a quiet place of reflection.

Yet that was just what happened. Disease, accident, and tragedy claimed several students’ lives during my time there.

The first was a girl named Halina. She wasn’t actually from Lipnica, but she was living at a rehabilitation center at the top of the village, just below Babia Gora. It was a center the Duchess of York had established for children recovering from the barrage of chemicals and radiation used to treat cancer. Halina was eighteen but trying to complete her first year of high school in Lipnica. Just before Christmas break, Halina disappeared. Several weeks later, during the two-week inter-semester winter break, I ran into the director of the rehab center.

“Halina died,” he said abruptly.

As she was from the west of Poland, several hours’ travel from Lipnica, I was unable to attend the funeral, and I’ve never visited her grave.

The cemetery was one of the last places I managed to visit during our 2013 trip, though. Â I’d come to pay respects to those students who’d died after the shock of Halina’s passing.

It took me little while, though, to realize how much had changed. The last remaining tree in the cemetery (a large evergreen) had been chopped down — a negative change. It always amazed me how the light of thousands of candles could illuminate the entire tree during All Saints’ Day, and that single tree, almost in the center of the cemetery, was a constant reminder of the renewal that follows death.

The chainlink fence around a small group of graves (including a couple of Hungarian markers) had been replaced with a modest chain barrier — a positive change. The two iron crosses, in the center of the cemetery but toward the rear fence, always stood out, and the chain link fence seemed an inappropriate addition.

But I hadn’t come to see how much the cemetery had changed; I’d come to pay respects to three people, all of whom were taken entirely too soon.

Marcela finished up her freshman year in high school as I left Poland in 1999. I didn’t know her well: I only taught her class a couple of times a week, and I worked with her for only that one year. But when, back in the States, I learned that she and another girl, also my student, had drowned while on a trip to the Baltic Sea, that small connection seemed much more significant. A young girl, on a summer trip, drowns: it seems to be almost cruelly ironic.

Andrzej I knew much better, though. I taught him for three years, and when I returned to Poland in 2001, he’d graduated high school and we developed a friendly acquaintance as adults. Andrzej was truly popular with everyone. I don’t recall ever seeing him do anything other than smile. His death in a farming accident shocked and shook hundreds of people: his funeral mass was standing-room only, and for many weeks after, whenever I wandered into the cemetery, someone would be standing at his grave.

Emil Kowalczyk was Przewodniczący Rady Gminy (Chairman of the Municipal Council) for Lipnica Wielka, but more than that, he was a constant champion of the cultural heritage of Lipnica. I really only knew him in a professional capacity mainly by helping occasionally with some translation work. It was he, however, who arranged for me the traditional outfit required for admittance to the VIP seating area during Pope John Paul II’s visit in 1997. The mayor offered me the spot; Kowalczyk provided me the clothes. Always a kind and friendly soul, he died in 2005 of cancer at the young age of 64.

I visited the graves and felt a tinge of guilt that I didn’t bring flowers or a candle. I thought of the Jewish tradition of laying a rock on a grave as a mark of respect, but it seemed out of place, a Jewish tradition from a Catholic in a Catholic cemetery, as if I would just be going through some motions or other.

In the end, I just left after mumbling a short prayer over each grave, the same prayer L and I pray for Dziadek every night: “Have mercy on his soul and give him peace.”

On the way out, I noticed a fresly dug grave. Unlike in most US cemeteries, the graves in Lipnica are dug manually: a couple of guys with shovels, picks, and a few planks. Winter graves are hellishly difficult because of the depth of the frost line. Diggers must first thaw the earth before they can begin with the shoves and picks. In the summer, it must be relatively quick work.